Short Wave Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antique Radio Classified

ANTIQUE RADIO CLASSIFIED VOLUME 3 AUGUST 19E6 NUMBER 8 • QUAKER OATS CRYSTAL SET From the collection of Randall Renne - Dixon, IL THE NATIONAL PUBLICATION FOR BUYERS AND SELLERS OF OLD RADIOS AND RELATED ITEMS - PUBLISHED MONTHLY ANTIQUE RADIO CLASSIFIED Publishing Details Classified Ads Each subscriber is entitled to one 20 word classified ad Antique Radio Classified lUSPS 735-0901 is free of charge per issue. Additional words over the limit published monthly. 12 times yearly. at a suoscrip- are 10C per word. Multiple insertions of same ad are tion rate of $18.00 per year Second Class and discouraged. This is to allow for a varied ad content in each issue. Multiple insertion ads for more than $24.00 First Class mailing rates, by G.B.S. Enter- 2 issues must be run as a display ad. All ads must be prises, 9511 Sunrise Blvd.. 8.1-23. Cleveland, Ohio printed neatly and be received by the 8th of the month 44133. (216) 582-3094. before next issue. See classified ad details elsewhere Second-class postage paid at Cleveland, OH. in this issue. Publisher and Editor Gary B. Schneider. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to address Payment above. Copyright 1986... Antique Radio Classified All ads must be paid for in advance. Make checks payable to Antique Radio Classified. Purpose Antique Radio Classified is published for people in- Subscription Rate volved in the radio collecting hobby. Its purpose is to Subscriptions are available on a yearly basis. $18.00 stimulate growth of the hobby thru the buying, selling. per year Second Class and $24.00 First Class mailing and trading of radios and related items. -

BETS-5 Issue 1 November 1, 1996

BETS-5 Issue 1 November 1, 1996 Spectrum Management Broadcasting Equipment Technical Standard Technical Standards and Requirements for AM Broadcasting Transmitters Aussi disponible en français - NTMR-5 Purpose This document contains the technical standards and requirements for the issuance of a Technical Acceptance Certificate (TAC) for AM broadcasting transmitters. A certificate issued for equipment classified as type approved or as technically acceptable before the coming into force of these technical standards and requirements is considered to be a valid and subsisting TAC. A Technical Acceptance Certificate is not required for equipment manufactured or imported solely for re-export, prototyping, demonstration, exhibition or testing purposes. i Table of Contents Page 1. General ...............................................................1 2. Testing and Labelling ..................................................1 3. Standard Test Conditions ..............................................2 4. Transmitting Equipment Standards .....................................3 5. Equipment Requirements ..............................................4 6. RF Carrier Performance Standards .................................... 5 6.1 Power Output Rating .................................................5 6.2 Modulation Capability ................................................5 6.3 Carrier Frequency Stability ............................................6 6.4 Carrier Level Shift ...................................................7 6.5 Spurious Emissions -

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa Radio is by far the dominant and most important mass medium in Africa. Its flexibility, low cost, and oral character meet Africa's situation very well. Yet radio is less developed in Africa than it is anywhere else. There are relatively few radio stations in each of Africa's 53 nations and fewer radio sets per head of population than anywhere else in the world. Radio remains the top medium in terms of the number of people that it reaches. Even though television has shown considerable growth (especially in the 1990s) and despite a widespread liberalization of the press over the same period, radio still outstrips both television and the press in reaching most people on the continent. The main exceptions to this ate in the far south, in South Africa, where television and the press are both very strong, and in the Arab north, where television is now the dominant medium. South of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo River, radio remains dominant at the start of the 21St century. The internet is developing fast, mainly in urban areas, but its growth is slowed considerably by the very low level of development of telephone systems. There is much variation between African countries in access to and use of radio. The weekly reach of radio ranges from about 50 percent of adults in the poorer countries to virtually everyone in the more developed ones. But even in some poor countries the reach of radio can be very high. In Tanzania, for example, nearly nine out of ten adults listen to radio in an average week. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

_______________________ _____________________________________ En’, IWJI ‘III ‘" 11fl4-XIIH Il,. S-ki United States Department of the Interior NatiQnai Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property Instorir name Massje Wireless Station other n;uneAsite number ‘ ‘ Pt]-’ 2. bntion street & nuinber 1300 Frenchtown Road not for publication: citxtown: East Greenwich viciuit N/A state: RI toil ntv Ken Msle: 0 0 3 ZIp isle: 02 8 1 8 3. Classificafion Ownership of Pms’rty: Private Tategorv of Piopertv: Building Nu mnber of flesoiLrtes with] ii Property: - Ton t riInit ii ig No ii 0 nt rihuli ng htHldilgs sites structures objects 1 p Total Number of toiitnhimting res4imrees previously listed in time National Ihgister Name ol related immumltiple property listiuig N/A ___________________________________________________________________ ______________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________ USDIiNPS Yil[fl Registration Form Page 2 Property name Nassie Wireless Station, Kent Cty. , East Greenwich, RI 4. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the tlt’signated authority under time National ii istonc Preservation Act of 1986, as amnendeil, I hereby certify that this_x_ nonminatiomi request for tleternii nat ion of eligibility meets the documnemitation standards for registermg pmoiwiies in the Nationi I Register of ii istoric Places and meets the procedural amid professional requ irenien ts set forth in 36 CFI1 Pa.rt. 60. In mmiv opi mm ion, tIme property J nieets does not meet the National Register Cr term. - See continuation sheet. 1. ‘ Gc Signature of certifying official Date State or Feil era I agency a mid himmriLil En umy op i iii u m, the i11 pe rtv meets ltfl’s mot uieet tIme Nat immII legister t-ri te ii a. -

P1-Extreme Amplifier by David Sorlien, Revised and Updated by Stephen Keller

Introduction to Tube Amplifier Theory: 10.02.15 Featuring the AX84 P1-eXtreme Amplifier by David Sorlien, revised and updated by Stephen Keller The P1-eX amplifier is a simple three-stage vacuum tube electric guitar amplifier. As outlined in Fig. 1, it consists of two preamp stages driving a power amp stage. Depending on the choice of output tube, this amp is can deliver between 7 and 15 watts into a 4-, 8-, or 16-ohm load. Fig. 1: P1-eX block diagram Placed between the two preamp stages is a preamp volume control. In a similar manner, the bass, middle, and treble tone controls and a master volume control are placed between the preamp and the final power amp stage. The guitar amplifier performs two primary functions: One, it amplifies the small voltages and currents produced by the guitar pickup into a signal powerful enough to drive a speaker. Two, it shapes the frequency response, tonality, and distortion characteristics of the raw guitar signal into a form pleasing to the musician. To better grasp how a guitar amplifier accomplishes these functions, let©s take a walk through the inner workings of the AX84 P1-eXtreme amp (P1-eX). For reference, there is copy of revision 06.03.16 of the schematic provided in Appendix 1 at the end of this document. To fully understand how a guitar amp works, even a simple one like the P1-eX, you must know how to read schematic diagrams, and understand what things like resistors and capacitors are. You also need some knowledge of basic algebra and electronic theory. -

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

The Market Leader in Over-The-Air Broadcasting Solutions

Connecting What’s Next The Market Leader in Over-the-Air Broadcasting Solutions GatesAir efficiently leverages broadcast spectrum to maximize performance for multichannel TV and radio services, offering the industry’s broadest portfolio to help broadcasters wirelessly deliver and monetize content. With nearly 100 years in broadcasting, GatesAir’s exclusive focus on the over-the-air market helps broadcasters optimize services today and prepare for future revenue-generating business opportunities. All research, development and innovation is driven from the company’s facilities in Mason, Ohio and supported by the long-standing manufacturing center in Quincy, Illinois. GatesAir’s turnkey solutions are built on three pillars: Content Transport, TV Transmission, and Radio Transmission. GatesAir’s globally renowned Intraplex range comprises the Transport pillar, enabling audio contribution and distribution (along with data) over IP and TDM networks. Intraplex solutions provide value for broadcasters for point-to-point (STL, remote broadcast) and multipoint (single-frequency networks, syndicated distribution) connectivity. GatesAir continues to innovate robust and reliable solutions for traditional RF STL connections that can also accommodate IP traffic. In larger transmitter networks, Simulcasting technology ensures all GatesAir transmitters are time-locked for synchronous, over-the-air content delivery. Powering over-the-air analog and digital radio/TV stations and networks worldwide with the industry’s most operationally efficient transmitters is a longtime measure of success for GatesAir. Groundbreaking innovations in low, medium and high- power transmitters reduce footprint, energy use and more to establish the industry’s lowest total cost of ownership. Support for all digital standards and convergence with mobile networks ensure futureproof systems. -

The Beginner's Handbook of Amateur Radio

FM_Laster 9/25/01 12:46 PM Page i THE BEGINNER’S HANDBOOK OF AMATEUR RADIO This page intentionally left blank. FM_Laster 9/25/01 12:46 PM Page iii THE BEGINNER’S HANDBOOK OF AMATEUR RADIO Clay Laster, W5ZPV FOURTH EDITION McGraw-Hill New York San Francisco Washington, D.C. Auckland Bogotá Caracas Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal New Delhi San Juan Singapore Sydney Tokyo Toronto McGraw-Hill abc Copyright © 2001 by The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as per- mitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-139550-4 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-136187-1. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trade- marked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringe- ment of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

A Century of WWV

Volume 124, Article No. 124025 (2019) https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.124.025 Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology A Century of WWV Glenn K. Nelson National Institute of Standards and Technology, Radio Station WWV, Fort Collins, CO 80524, USA [email protected] WWV was established as a radio station on October 1, 1919, with the issuance of the call letters by the U.S. Department of Commerce. This paper will observe the upcoming 100th anniversary of that event by exploring the events leading to the founding of WWV, the various early experiments and broadcasts, its official debut as a service of the National Bureau of Standards, and its role in frequency and time dissemination over the past century. Key words: broadcasting; frequency; radio; standards; time. Accepted: September 6, 2019 Published: September 24, 2019 https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.124.025 1. Introduction WWV is the high-frequency radio broadcast service that disseminates time and frequency information from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. WWV has been performing this service since the early 1920s, and, in 2019, it is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the issuance of its call sign. 2. Radio Pioneers Other radio transmissions predate WWV by decades. Guglielmo Marconi and others were conducting radio research in the late 1890s, and in 1901, Marconi claimed to have received a message sent across the Atlantic Ocean, the letter “S” in telegraphic code [1]. Radio was called “wireless telegraphy” in those days and was, if not commonplace, viewed as an emerging technology. -

6\ M?L/ K7 Gmwy 4 I ' + /‘4 I- E 7 4-‘1 :"I'yl’‘‘‘‘ ‘N I ‘ 7'0 LP 2: J- = ' '

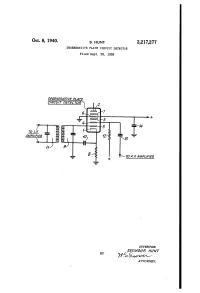

Oct.’ 8, 1940. s. HUNT £2,217,277 ' ‘ DEGENERATIVE PLATE cmcun: DETECTOR Filed Sept. '28, 19:8 DEGENERAT/VE PLATE __———_C/RCU/T DETECTOR | /2 6\ M?l/ k7 gmwy 4 i ' + /‘4 i- E 7 4-‘1 :"I'Yl’‘‘‘‘ ‘n I ‘ 7'0 LP 2: J- = ' ' a . °~ I ?|__' I ~ 70 A. E AMPLIFIER INVENTOR. Ilse MOUR HUNT BY ATTORNEY. Patented Oct. 8, 1940 2,2l7,277 UNITED STATES F ICE 2,217,277 DEGENERAT'IVE PLATE CIRCUIT DETECTOR Seymour Hunt, Jackson Heights, Long llsland, N. Y., assignor to Radio Corporation of Amer ica, a corporation of Delaware Application September 28, 1938, Serial No. 232,075 6 Claims. (Cl. 256-4237) My present invention relates to detector cir art are fully acquainted with the construction of cuits, and more particularly to degenerative plate superheterodyne receivers, it is not believed nec circuit detectors capable of substantially ampli essary to explain the construction thereof at any fying the audio voltage output thereof. greater length. The output electrode for the 5 One of the main objects of this invention is to detector circuit includes electrode 4. Preferably, provide a detector of the in?nite impedance type this electrode is a wound grid. The latter is con which includes an electronic section having a nected through load resistor 52 to the plus B negative mutual conductance characteristic terminal of any desired direct current source, which functions to amplify the audio output of such as the usual direct current energizing source 10 the detector. of a radio receiver. The coupling condenser l3 Another important object is to provide in a transmits the audio voltage, in ampli?ed form, biased plate circuit detector of the degenerative to the following audio ampli?er for ?nal repro type a negative mutual conductance section duction. -

Electrostatic Design and Characterization of a 200 Kev Photogun and Wien Spin Rotator

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Electrical & Computer Engineering Theses & Dissertations Electrical & Computer Engineering Spring 2021 Electrostatic Design and Characterization of a 200 keV Photogun and Wien Spin Rotator Gabriel G. Palacios Serrano Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/ece_etds Part of the Computer Engineering Commons, Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Palacios Serrano, Gabriel G.. "Electrostatic Design and Characterization of a 200 keV Photogun and Wien Spin Rotator" (2021). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Dissertation, Electrical & Computer Engineering, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/mf9f-r453 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/ece_etds/224 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electrical & Computer Engineering at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electrical & Computer Engineering Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELECTROSTATIC DESIGN AND CHARACTERIZATION OF A 200 keV PHOTOGUN AND WIEN SPIN ROTATOR by Gabriel G. Palacios Serrano B.S. August 2014, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico M.S. May 2017, Old Dominion University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ELECTRICAL AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2021 Approved by: Helmut Baumgart (Director) Carlos Hernández (Member) Linda Vahala (Member) Mohammad Obeid (Member) Gon Namkoong (Member) ABSTRACT ELECTROSTATIC DESIGN AND CHARACTERIZATION OF A 200 keV PHOTOGUN AND WIEN SPIN ROTATOR Gabriel G. Palacios Serrano Old Dominion University, 2021 Director: Dr. -

SBE Comments to FINAL AM Improvement Docket

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) MB Docket No. 13-153 To: The Commission COMMENTS OF THE SOCIETY OF BROADCAST ENGINEERS, INCORPORATED 1. The Society of Broadcast Engineers, Incorporated (“SBE”)1 respectfully submits its Comments in response to portions of the Commission’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 13-139, 28 FCC Rcd. 15221, released October 31, 2013 in the above-captioned proceeding (the “Notice”).2 The Notice proposes “to introduce a number of possible improvements to the … AM… radio service and the rules pertaining to AM broadcasting.” The Commission also seeks “to revitalize further the AM band by identifying ways to enhance AM broadcast quality and proposing changes to our technical rules that would enable AM stations to improve their service.” The Commission proposes to “help AM broadcasters better serve the public, thereby advancing the Commission’s fundamental goals of localism, competition, and diversity in broadcast media.” SBE applauds this effort and offers the following comments on some of the technical issues raised in this proceeding. Specifically, SBE offers its comments on four issues that will provide both immediate and long-term relief to AM broadcast licensees: 1 SBE is the national association of broadcast engineers and technical communications professionals, with more than 5,000 members worldwide. 2 The Notice of Proposed Rulemaking was published in the Federal Register November 20, 2013. See, 78 Fed. Reg. 69629. 1