Malaysia Brunei at a Glance: 2001-02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) 1946 - 1999 Azeem Fazwan Ahmad Farouk

Institut für Asien- und Afrikawissenschaften Philosophische Fakultät III der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Culture and Politics: An Analysis of United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) 1946 - 1999 Azeem Fazwan Ahmad Farouk Südostasien Working Papers No. 46 Berlin 2011 SÜDOSTASIEN Working Papers ISSN: 1432-2811 published by the Department of Southeast Asian Studies Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Unter den Linden 6 10999 Berlin, Germany Tel. +49-30-2093 66031 Fax +49-30-2093 66049 Email: [email protected] The Working Papers do not necessarily express the views of the editors or the Institute of Asian and African Studies. Al- though the editors are responsible for their selection, responsibility for the opinions expressed in the Papers rests with the authors. Any kind of reproduction without permission is prohibited. Azeem Fazwan Ahmad Farouk Culture and Politics: An Analysis of United Malays National Organi- sation (UMNO) 1946 - 1999 Südostasien Working Papers No. 46 Berlin 2011 Table of Contents Preface........................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Organizational Structure and Centralization.................................................................................................. -

Islamic Political Parties and Democracy: a Comparative Study of Pks in Indonesia and Pas in Malaysia (1998-2005)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS ISLAMIC POLITICAL PARTIES AND DEMOCRACY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PKS IN INDONESIA AND PAS IN MALAYSIA (1998-2005) AHMAD ALI NURDIN S.Ag, (UIN), GradDipIslamicStud, MA (Hons) (UNE), MA (NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAM NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2009 Acknowledgements This work is the product of years of questioning, excitement, frustration, and above all enthusiasm. Thanks are due to the many people I have had the good fortune to interact with both professionally and in my personal life. While the responsibility for the views expressed in this work rests solely with me, I owe a great debt of gratitude to many people and institutions. First, I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, who was my principal supervisor before he transferred to Flinders University in Australia. He has inspired my research on Islamic political parties in Southeast Asia since the beginning of my studies at NUS. After he left Singapore he patiently continued to give me advice and to guide me in finishing my thesis. Thanks go to him for his insightful comments and frequent words of encouragement. After the departure of Dr. Priyambudi, Prof. Reynaldo C. Ileto, who was a member of my thesis committee from the start of my doctoral studies in NUS, kindly agreed to take over the task of supervision. He has been instrumental in the development of my academic career because of his intellectual stimulation and advice throughout. -

Dewan Rakyat

Bil. 77 Selasa 5 Disember 2000 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KESEPULUH PENGGAL KEDUA MESYUARAT KETIGA KANDUNGAN . JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANY AAN-PERTANY AAN (Halaman I) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBA WA KE DALAM MESYUARAT (Halaman 14) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan 2001 ~ Jawatankuasa : Jadual- Maksud B.48 (Halaman 14) Maksud B.50 (Halaman 38) USUL-USUL: Anggaran Pembangunan 2001 Jawatankuasa : Maksud P.48 (Halaman 14) Maksud P.50 (Halaman .38) Diterbitkan oleh CAWANGAN DOKUMENTASI PARLIMEN MALAYSIA 2000 - ---------- .. DR.05.12.2000 AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Amat Berbahagia Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Tun Dr. Mohamed Zahir bin Haji Ismail, S.S.M., P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K. J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhorrnat Perdana Menteri, Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad, D.K.(Brunei), D.K.(Perlis), D.K.(Johor), D.U.K., S.S.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P. (Sarawak), D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., S.P.C.M., S.S.M.T., D.U.M.N., P.l.S. (Kubang Pasu) Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri, Dato' Seri Abdullah bin Haji Ahmad Badawi, D.G.P.N., D.S.S.A., D.M.P.N., D.J.N., K.M.N., A.M.N., S.P.M.S. (Kepala Batas) Yang Berhorrnat Menteri Pengangkutan, Dato' Seri Dr. Ling Liong Sik, S.P.M.P., D.G.S.M., D.P.M.P. D.P.M.S. (Labis) Menteri Kerja Raya, Dato' Seri S. -

Politik Dimalaysia Cidaip Banyak, Dan Disini Sangkat Empat Partai Politik

122 mUah Vol. 1, No.I Agustus 2001 POLITICO-ISLAMIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA IN 1999 By;Ibrahim Abu Bakar Abstrak Tulisan ini merupakan kajian singkat seJdtar isu politik Islam di Malaysia tahun 1999. Pada Nopember 1999, Malaysia menyelenggarakan pemilihan Federal dan Negara Bagian yang ke-10. Titik berat tulisan ini ada pada beberapa isupolitik Islamyang dipublikasikandi koran-koran Malaysia yang dilihat dari perspektifpartai-partaipolitik serta para pendukmgnya. Partai politik diMalaysia cidaip banyak, dan disini Sangkat empat partai politik yaitu: Organisasi Nasional Malaysia Bersatu (UMNO), Asosiasi Cina Ma laysia (MCA), Partai Islam Se-Malaysia (PMIP atau PAS) dan Partai Aksi Demokratis (DAP). UMNO dan MCA adalah partai yang berperan dalam Barisan Nasional (BA) atau FromNasional (NF). PASdan DAP adalah partai oposisipadaBarisanAltematif(BA) atau FromAltemattf(AF). PAS, UMNO, DAP dan MCA memilikipandangan tersendiri temang isu-isu politik Islam. Adanya isu-isu politik Islam itu pada dasamya tidak bisa dilepaskan dari latar belakang sosio-religius dan historis politik masyarakat Malaysia. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ ^ <•'«oJla 1^*- 4 ^ AjtLtiLl jS"y Smi]?jJI 1.^1 j yLl J J ,5j^I 'jiil tJ Vjillli J 01^. -71 i- -L-Jl cyUiLLl ^ JS3 i^LwSr1/i VjJ V^j' 0' V oljjlj-l PoUtico-Islnndc Issues bi Malays bi 1999 123 A. Preface This paper is a short discussion on politico-Islamic issues in Malaysia in 1999. In November 1999 Malaysia held her tenth federal and state elections. The paper focuses on some of the politico-Islamic issues which were pub lished in the Malaysian newsp^>ers from the perspectives of the political parties and their leaders or supporters. -

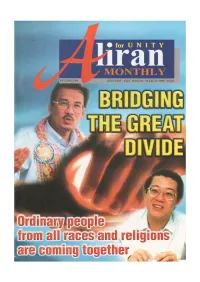

Writes to Guan Eng 4 Guan Eng Replies to Anwar 5 Changing Trmes 8 Three Feasts and a (Soap) Opera 10

u~t·r<~»••nt parties and NGOs, people from all races n!lta•iol'ia are coming together. he Anwar saga has Naturally these different and must be further pro g been an important ral groups with similar goals moted. lying point for the joined forces in the Gagasan reformasi movement. But con and Gerak coalitions to pursue The first item is a set of let cern for Anwar's sacking, as these goals vigorously. ters bet·ween Anwar and sault and unjust treatment Guan Eng from their respec generally have extended into The overall struggle has be tive jails: they exchange fes concern over wider issues. come more comprehensive tive greetings and discuss thb too: Justice for Anwar, for issue of ethnic relations. Sabri The ISA must go. Undemo Guan Eng, for Irene Zain's article Clznllging Times cratic laws must be reviewed Fernandez, for the 126 comments on pre\'ious ethnic so as to guarantee the rakyat's charged for illegal assembly, barriers breaking down. It is rights and liberties. The inde and now, for all prisoners too. a piece that lifts up the spirit. pendence and integrity of the No unjust toll hikes, boycott OJ Muzaffar Tate reports on judiciary, the Attorney irresponsible newspapers, en three functions he attended in Generalis chambers and the sure a free and fair election in Kuala Lumpur, while Anil Police must be restored. Sabah, etc. !\ietto and R.K. Surin write about their e>..perienceattend Cronyism must be gotten rid In this issue of AM, we carry ing a forum in Penang. -

Shell Business Operations Kuala Lumpur:A Stronghold

SHELL BUSINESS OPERATIONS KUALA LUMPUR: A STRONGHOLD FOR HIGHER VALUE ACTIVITIES etting up their operations nearly tial. It sends a strong statement that SBO-KL • SBO-KL’s success in Malaysia two decades ago, The Shell Busi- does not offer a typical GBS location, but was attributed to three key ness Operations Kuala Lumpur offers an entire ecosystem that is constantly aspects – talent quality & (SBO-KL) which is located in growing and developing. availability, world class infra- Cyberjaya, has come a long way. structure, and govt support. SInitially known as Shell IT International (SITI), Frontrunner In The Field • Expansion plans are based on the company has reinvented itself into the Currently, SBO-KL is one of seven global busi- skills, not scale – hiring from multifunctional shared services company ness operations serving clients worldwide, different sectors and industries it is today. with the current focus of being a hub of allows for new markets to be expertise and centre of excellence. tapped into when it comes to Malaysia, Meeting All Requirements Amongst the shared services in Malaysia, creative solutions. The centre’s setup in Malaysia was attributed SBO-KL has the widest portfolio, comprising • High Performance Culture cre- to three key aspects – government support, of business partners and services in the areas ates employees that are holistic talent availability and infrastructure. Having of IT, Finance, HR, Operations, Contracting in thinking and have a desire been granted MSC status, support, and and Procurement, Downstream Business to improve the bottom-line of policies that was favourable, this was a clear (Order-to-delivery, Customer Operation, the organisation. -

DR MAHATHIR BERLEPAS KE ASIA TENGAH (Bernama 15/07/1996)

15 JUL 1996 DR MAHATHIR BERLEPAS KE ASIA TENGAH KUALA LUMPUR, 15 Julai (Bernama) -- Perdana Menteri Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad hari ini berlepas dari sini untuk mengadakan lawatan rasmi ke Republik Kyrgyz dan Republik Kazakhstan di Asia Tengah untuk meningkatkan hubungan dua hala. Dr Mahathir yang diiringi isterinya, Datin Seri Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali, akan berada di Republik Kyrgyz mulai hari ini sehingga Khamis, diikuti lawatan ke Kazakhstan sehingga Sabtu. Delegasi Perdana Menteri termasuk lima menteri kabinet -- Menteri luar Datuk Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, Menteri Kerja Raya Datuk Seri S.Samy Vellu, Menteri Perusahaan Utama Datuk Seri Dr Lim Keng Yaik, Menteri Kebudayaan, Keseniaan dan Pelancongan Datuk Sabbaruddin Chik dan Menteri di Jabatan Perdana Menteri Datuk Dr Abdul Hamid Othman. Turut dalam delegasi itu tiga Menteri Besar -- Tan Sri Wan Mokhtar Ahmad dari Terengganu, Datuk Abdul Ghani Othman (Johor) dan Datuk Seri Shahidan Kassim (Perlis) -- serta Ketua Menteri Melaka Datuk Seri Mohd Zin Abdul Ghani. Delegasi perniagaan dengan 81 anggota yang diketuai Pengerusi dan Ketua Eksekutif Penerbangan Malaysia Tan Sri Tajudin Ramli turut mengiringi Dr Mahathir ke kedua-dua negara. Lawatan Perdana Menteri ke kedua-dua negara itu sebagai memenuhi jemputan Presiden Kyrgyz Askar Akayev yang mengadakan lawatan rasmi ke negara ini pada Julai tahun lepas dan Presiden Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev yang melawat Malaysia pada Mei lepas. Lawatan itu merupakan yang pertama oleh seorang Perdana Menteri Malaysia ke kedua-dua negara itu. -- BERNAMA AZZ WE NMO . -

Aturan Urusan Mesyuarat

MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT ATURAN URUSAN MESYUARAT NASKHAH SAHIH/BAHASA MALAYSIA http:/(www.parlimen.gov.my HARI SELASA, 2 SEPTEMBER 2003 PUKUL 10.00 PAGI BiI.29 1 PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN BAGI JAWAB L1SAN (PM #34964 v1) 1. Dato' Ir. Mohd. Zin bin Mohamed [Shah Alam] minta MENTERI PERDAGANGAN ANT ARABAN GSA DAN INDUSTRI menyatakan apakah kerjasama ekonomi Asia Timur sebagai jawapan kepada globalisasi dan memecahkan benteng monopoli Amerika Syarikat dan Kesatuan Eropah. (PM #34032 v1) 2. Tuan Chang See Ten [Gelang Patah] minta MENTERI DALAM NEGERI menyatakan sejauh manakah kejayaan tercapai dalam usaha Kerajaan untuk menerapkan semula bekas banduan ke dalam masyarakat. (PM #34042 v1) 3. Drs. Haji Abu Bakar bin Othman [Jerlun] minta MENTERI PENDIDIKAN menyatakan berapakah jumlah peruntukan yang telah diberikan kepada Sekolah Agama Rakyat (SAR) semenjak tahun 1999 sebelum ia diberhentikan dan apakah kesannya terhadap institusi tersebut dan masyarakat sehingga kini. (PM #34080 v1) 4. Dato' Othman bin Abdul [Pendang] minta MENTERI DALAM NEGERI menyatakan jumlah kakitangan Kerajaan yang terlibat dengan Pasukan Khas Persekutuan Malaysia (PKPM) dan Jabatan-jabatan terlibat. Mengapa Kementerian mengambil masa yang agak lama untuk mengesan kegiatan PKPM. 2 AUM DR 02/09/2003 (PM #35220 v1) (PM #34092 v1) 5. Tuan Haji Amihamzah bin Ahmad [Lipis1 minta MENTERI TANAH DAN PEMSANGUNAN KOPERASI menyatakan sejauh manakah FELDA berjaya menangani masalah pemilikan tanah dan apakah langkah-Iangkah yang diambil untuk mengekalkan pemilikan ini setelah peneroka diberi hak milik. (PM #35051 v1) 6. Tuan Kerk Kim Hock [Kota Melaka] minta MENTERI PENDIDIKAN menyatakan butir-butir berikut bagi projek makmal komputer sekolah bagi semua fasa:- (a) jumlah makmal komputer bagi tiap-tiap negeri; dan (b) jumlah yang telah disiapkan dan masalah yang dihadapi dan puncanya. -

Fight AES Fines, PAS's Mahfuz Tells Road Users Malaysian Insider

Fight AES fines, PAS’s Mahfuz tells road users Malaysian Insider October 31, 2012 By Ida Lim KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 31 ― A PAS lawmaker today urged road users not to pay off traffic summonses issued under the federal government’s controversial Automated Enforcement System (AES), saying that they should claim trial to the offences instead. “Now I want to ask, if the government refuses to delay the implementation of the AES and withdraw all summonses issued, everyone who receives the AES summonses don’t need to pay the RM300 compound, instead follow this instruction to go to court...” PAS vice-president Datuk Mahfuz Omar said at a press conference today. He said that Pakatan Rakyat (PR) was prepared to provide lawyers to represent those who chose to contest the summonses in court. Yesterday, PR said it would suspend approval for the AES’s implementation in the four states of Penang, Selangor, Kedah and Kelantan, to allow for further discussion and public feedback. Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng yesterday said that PR’s move would mean that 331 out of the planned 831 cameras under the nationwide AES scheme will not be installed. The AES cameras, which detects speeding motorists and those who beat traffic lights, is in its pilot phase, with 14 installed in Perak, Kuala Lumpur, Selangor and Putrajaya. Today, Umno MP Datuk Bung Mokhtar Radin also crossed the political divide today and backed the opposition PR pact in calling for Putrajaya to suspend enforcing the controversial traffic system, saying it could be used as electoral fodder against the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN). -

Penyata Rasmi Parlimen Parliamentary Debates

Jilid IV Bari Selasa Bil. 16 lOhb Mei 1994 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RAKYAT House of Representatives PARLIMEN KELAPAN Eighth Parliament PENGGAL KEEMPAT Fourth Session KAND UN GAN RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perlembagaan (Pindaan) 1994 [Ruangan 2583] Rang Undang-undang Pilihanraya (Pindaan) 1994 [Ruangan 2714] Rang Undang-undang Kesalahan Pilihanraya (Pindaan) 1994 [Ruangan 2732] Rang Undang-undang Perkapalan Saudagar (Pindaan) 1994 [Ruangan 2793] USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan yang dibebaskan daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat dan Penangguhan [Ruangan 2686] D!CETAK OLEH PERCETAKAN NASIONAL MALAYSIA BERHAD, • CAW ANGAN JOHOR BAHRU ....... 1998 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KELAPAN Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG KEEMPAT AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATO' MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAn ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri, DATO' SERI DR MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, D.K.1., D.U.K., S.S.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., S.P.C.M., S.S.M.T., D.U.N.M., P.1.s. (Kubang Pasu) Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Kewangan, DATO' SERI ANWAR BIN IBRAHIM, S.S.A.P., S.S.S.A., D.G.S.M., D.M.P.N. (Permatang Pauh) Yang Berhormat Menteri Pengangkutan, DATO' SERI DR LING LIONG S1K, s.P.M.P., D.P.M.S., D.P.M.P., D.G.S.M. -

109 a Abdul Hamid Othman, 44–45 Abdul Karim Amrullah, 39 Abdul

INDEX A curriculum, in, 71–74 Abdul Hamid Othman, 44–45 history of, 16–18 Abdul Karim Amrullah, 39 Indonesian graduates, 36–42 Abdul Malik Karim Amrullah Malaysian graduates, 42–47 (Hamka), 38–40, 45 methodology, 75–77 Abdul Nasser, Gamal, 25, 27, 29, 66 modernism, 22–25 Abdul Shukor Husin, 44, 46–47 nationalism, 25–28 Abdullah Ahmad, 39 religious authority, and, 9–10 Abdullah Badawi, 44 Singapore graduates, 47–52 Abdullah Sheikh Balfaqih, 49 student associations in, 80–82 Abdurrahman Wahid, 37 al-Banna, Hassan, 28–29 Abrurahman Shihab, 40 al-Hadi, Syed Shaikh, 34–35 Abu Bakar Hashim, 48, 50–51 Al-Halal Wal Haram Fil Islam (The Administration of Muslim Law Lawful and the Prohibited in Act (AMLA), 10, 48 Islam), 31 Ahmad’ Atta Allah Suhaimi, 35 “Al-I’jaz at-Tasryii li al-Quran Ahmed Fuad I, 25 al-Karim” (The Wonders of Ahmed Fuad II, 25 Al-Quran in accordance to Akademi Islam, 15 Law), thesis, 41 al-Afghani, Jamal al-Din, 20, 23–24 al-Imam, magazine, 34 Al-Azhar University, 5, 8, 11–13, Al-Jazeera, 31 15, 29, 34–35, 54–65, 93–100 al-Manar, magazine, 34 Al-Qaradawi, Yusuf, and, 30–33 Al-Mawdudi, Abu Ala, 28 colonialism, and, 18–22 Al-Muáyyad Shaykh, 17 culture shock in, 66–71 Al Qaeda, 6 109 18-J03388 07 Tradition and Islamic Learning.indd 109 1/3/18 11:20 AM 110 Index Al-Qaradawi, Yusuf, 13 C Al-Azhar University, and, 30–33 Cairo University, 37 al-Waqaí al-misriyya, publication, Caliphate system, 14, 16 24 Camp David Accords, 26 al-Zahir Baybars, al-Malik, 17 career guidance, 86 Ali Abu Talib, 2 Catholicism, 1 alim, 2, 4–5, 10, 14, 37–38, -

Ftenrurces Rruo Loc* Lsun Oru Jnvn Huub De Jonge Mnnruz Nl-Ttnutsi

lNDONESlAN,rounuL FoR rsLAMrc sTUDIES Volume5, Number2,1998 FtenruRces Rruo Loc* lsuN oru Jnvn Huub de Jonge MnnruZ nl-Ttnutsi (0. 1338/te1e1: Aru lrurru-ecruAL BtocnRpHv Abduirahman Mas'ud lsllrrr OaseRVED:THE CnsE or CorurEuponRRv MRuvstR Laurent Metzger "TnE Cusn oF ClvlLlzATloN"; A Pnocruosts oF THE Furune oR THE Lunr or rnE Pnsr Taufik Abdullah tsisN 0215-0492 $II]DHN,Ail|ilfi ffi Vol.v n0.2,1998 Epnoruer Boanp' Harun Nasution Mnstuhu M. Quraish Shihab A. Aziz Dahlan M. Satria Et't'endi Nabilah Lubis M. Yunnn Yusuf Komaruddin Hidayat M. Din Syamsuddin Muslim Nasution Wahib Mu'thi Eprron-rx-Cnrrp, Azyumardi Azra Eonons, Saiful Mujani Hendro Prasetyo lohan H. Meuleman Didin Syat'ruddin Ali Munhanif Assisrelirs ro rHE EDrroR: Arief Subhan Oman Fathurrahman Heni Nuroni Er.rcr-rsH LeNcuecs Aovrson' Donald Potter Anesrc LeNcuecn Aovrson, Nursamad CovrR DrsrcNrn' S. Prinka STUDIA ISLAMIKA (ISSN 0215-049D is a journal published quarterly by the lnstitut Agama Islnm Negeri IAIN, the State lnstitute t'or Ishrmic Studied Syarif Hidayatullah, Jnkarta. (SIT DEPPEN No. L29/SK/DITIENIPPGISTT/l.97O and sponsored by the Depnrtment of Religious At't'airs of the Republic of Indonesia. It specializes in Indonesian lslamic studies, and is intended to communicate original researches and current issues on the subject. This journal warmly welcomes contributions t'rom scholars of related disci- plines. All nrticles published do not necessarily represent the aiews of the journal, or other institutions to which it is ffiliated. They are solely the aiews of the authors. The articles contained in this journal haoe been ret'ereed by the Board of Editors.