Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intra-Actions with Educational Media at the National Film Board of Canada, 1960-2016

Making Waves: Intra-actions with Educational Media at the National Film Board of Canada, 1960-2016 CAROLYN STEELE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PRODRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE APRIL 2017 YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO © Carolyn Steele 2017 ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to excavate the narrative of educational programming at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) from 1960 to 2016. The producers and creative staff of Studio G – the epicentre of educational programming at the NFB for over thirty years – produced extraordinarily diverse and innovative multimedia for the classroom. ‘Multimedia’ is here understood as any media form that was not film, including filmstrips, slides, overhead projecturals, laserdiscs and CDs. To date, there have been no attempts to document the history of educational programming at the NFB generally, nor to situate the history of Studio G within that tradition. Over the course of five years, I have interviewed thirty-four NFB technicians, administrators, producers and directors in the service of creating a unique collective narrative tracing the development of educational media and programming at the NFB over the past fifty- six years and began to piece together an archive of work that has largely been forgotten. Throughout this dissertation, I argue that the forms of media engagement pioneered by Studio G and its descendants fostered a desire for, and eventually an expectation for specific media affordances, namely the ability to sequence or navigate media content, to pace one’s progress through media, to access media on demand and to modify media content. -

COUNCIL Agenda

ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda For the Meeting of January 24, 2018 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College 1. Opening Prayer 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Approval of the November 22, 2017 Minutes 4. Business arising from the Minutes 5. New Business a) Set the budget parameters for the upcoming fiscal year b) Bequest from the estate of Dorothy May Hayward c) Appointment of Architectural firm to design the new residence d) Approval of the Sketch Design Offer of Services for the new residence e) Development Committee f) Call for Honorary Degree Nominations 6. Reports from Committees, College Officers and Student Council a) Reports from Committees – Council Executive, Development, Finance & Admin. b) Report from Assembly c) Reports from College Officers and Student Council i) Warden ii) Dean of Studies iii) Development Office iv) Dean of Residence v) Spiritual Advisor vi) Bursar vii) Registrar viii) Senior Stick 7. Other Business 8. Adjournment ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL MINUTES For the Meeting of November 22, 2017 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College Present: D. Watt, G. Bak, P. Cloutier (Chair), J. McConnell, H. Richardson, J. Ripley, J. Markstrom, I. Froese, P. Brass, C. Trott, C. Loewen, J. James, S. Peters (Secretary) Regrets: D. Phillips, B. Pope, A. Braid, E. Jones, E. Alexandrin 1. Opening Prayer C. Trott opened the meeting with prayer. 2. Approval of the Agenda MOTION: That the agenda be approved as distributed. D. Watt / J. McConnell CARRIED 3. Approval of the September 27, 2017 Minutes MOTION: That the minutes of the meeting of September 27, 2017 be approved as distributed. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Published by Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Published by Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 Internet: onf-nfb.gc.ca/en E-mail: [email protected] Cover page: ANGRY INUK, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril © 2017 National Film Board of Canada ISBN 0-7722-1278-3 2nd Quarter 2017 Printed in Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS 2016–2017 IN NUMBERS MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNMENT FILM COMMISSIONER FOREWORD HIGHLIGHTS 1. THE NFB: A CENTRE FOR CREATIVITY AND EXCELLENCE 2. INCLUSION 3. WORKS THAT REACH EVER LARGER AUDIENCES, RAISE QUESTIONS AND ENGAGE 4. AN ORGANIZATION FOCUSED ON THE FUTURE AWARDS AND HONOURS GOVERNANCE MANAGEMENT SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES IN 2016–2017 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNEX I: THE NFB ACROSS CANADA ANNEX II: PRODUCTIONS ANNEX III: INDEPENDENT FILM PROJECTS SUPPORTED BY ACIC AND FAP AS THE CROW FLIES Tess Girard August 1, 2017 The Honourable Mélanie Joly Minister of Canadian Heritage Ottawa, Ontario Minister: I have the honour of submitting to you, in accordance with the provisions of section 20(1) of the National Film Act, the Annual Report of the National Film Board of Canada for the period ended March 31, 2017. The report also provides highlights of noteworthy events of this fiscal year. Yours respectfully, Claude Joli-Coeur Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson of the National Film Board of Canada ANTHEM Image from Canada 150 video 6 | 2016-2017 2016–2017 IN NUMBERS 1 VIRTUAL REALITY WORK 2 INSTALLATIONS 2 INTERACTIVE WEBSITES 67 ORIGINAL FILMS AND CO-PRODUCTIONS 74 INDEPENDENT FILM PROJECTS -

May 6–15, 2011 Festival Guide Vancouver Canada

DOCUMENTARY FILM FESTIVAL MAY 6–15, 2011 FESTIVAL GUIDE VANCOUVER CANADA www.doxafestival.ca facebook.com/DOXAfestival @doxafestival PRESENTING PARTNER ORDER TICKETS TODAY [PAGE 5] GET SERIOUSLY CREATIVE Considering a career in Art, Design or Media? At Emily Carr, our degree programs (BFA, BDes, MAA) merge critical theory with studio practice and link you to industry. You’ll gain the knowledge, tools and hands-on experience you need for a dynamic career in the creative sector. Already have a degree, looking to develop your skills or just want to experiment? Join us this summer for short courses and workshops for the public in visual art, design, media and professional development. Between May and August, Continuing Studies will off er over 180 skills-based courses, inspiring exhibits and special events for artists and designers at all levels. Registration opens March 31. SUMMER DESIGN INSTITUTE | June 18-25 SUMMER INSTITUTE FOR TEENS | July 4-29 Table of Contents Tickets and General Festival Info . 5 Special Programs . .15 The Documentary Media Society . 7 Festival Schedule . .42 Acknowledgements . 8 Don’t just stand there — get on the bus! Greetings from our Funders . .10 Essay by John Vaillant . 68. Welcome from DOXA . 11 NO! A Film of Sexual Politics — and Art Essay by Robin Morgan . 78 Awards . 13 Youth Programs . 14 SCREENINGS OPEning NigHT: Louder Than a Bomb . .17 Maria and I . 63. Closing NigHT: Cave of Forgotten Dreams . .21 The Market . .59 A Good Man . 33. My Perestroika . 73 Ahead of Time . 65. The National Parks Project . 31 Amnesty! When They Are All Free . -

NFB TEAM Producer Mixing Hugues Sweeney Serge Boivin Geoffrey Mitchell Administrator Jean-Paul Vialard Manon Provencher Luc Léger

nfb.ca/mytribe An interActive documentAry thAt Allows us to experience the worlds of 8 music fAns And see how the internet trAnsforms their interpersonAl relAtionships And helps forge their identity. 8 chArActers, 8 music styles, 8 views of the web And sociAl networks. PRESS KIT An interActive documentAry thAt Allows us to experience the worlds of 8 music fAns And see how the internet trAnsforms their interpersonAl relAtionships And helps forge their identity. 8 chArActers, 8 music styles, 8 views of the web And sociAl networks. nfb.ca/mytribe from reallife? is it a powerful conversely, engine for the distinctions construction or, of new communities? Can the virtual even be dissociated apprehend the world’s diversity if they are systematically searching for what is But “the can same?” Does the the reassurance Internet offered erase cultural by this virtual social life result in isolation, even to the exclusion of reality? “safe virtual home”,aspaceinwhichtoopenupandrevealone’strueself. How do users a becomes thus Web The validated. been has identity their that proof opinions—all and approval, of signs comments, receive to for their “fellows,” they choose a tribe to which to belong. In return for expressing themselves, sharing and posting, they expect Online social networks enable people to images share and music, emotions. information, Looking vehicle for forging an identity. each To his own “tribe”: Goth, emo, reggae, rap, vampire … Music is often more than a simple cultural product; it acts as a born between1982and1996.Thispermanentconnectionnecessarilychangeshowtheyseetheworld. users “connected”)—Web (for “C” Generation is This online. week a hours twenty than more spending are Quebecers young went, goes virtual, the definition remains unchanged but the practice revolutionizesTwenty everyday years after life. -

2012–2013 NFB Annual Report

Annual Report T R L REPO A NNU 20 1 2 A 201 3 TABLE 03 Governance OF CONTENTS 04 Management 01 Message from 05 Summary of the NFB Activities 02 Awards Received 06 Financial Statements Annex I NFB Across Canada Annex II Productions Annex III Independent Film Projects Supported by ACIC and FAP Photos from French Program productions are featured in the French-language version of this annual report at http://onf-nfb.gc.ca/rapports-annuels. © 2013 National Film Board of Canada ©Published 2013 National by: Film Board of Canada Corporate Communications PublishedP.O. Box 6100,by: Station Centre-ville CorporateMontreal, CommunicationsQuebec H3C 3H5 P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal,Phone:© 2012 514-283-2469 NationalQuebec H3CFilm Board3H5 of Canada Fax: 514-496-4372 Phone:Internet:Published 514-283-2469 onf-nfb.gc.ca by: Fax:Corporate 514-496-4372 Communications Internet:ISBN:P.O. Box 0-7722-1272-4 onf-nfb.gc.ca 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 4th quarter 2013 ISBN: 0-7722-1272-4 4thPhone: quarter 514-283-2469 2013 GraphicFax: 514-496-4372 design: Oblik Communication-design GraphicInternet: design: ONF-NFB.gc.ca Oblik Communication-design ISBN: 0-7722-1271-6 4th quarter 2012 Cover: Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley Graphic design: Folio et Garetti Cover: Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley Cover: Soldier Brother Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper 2012–2013 NFB Annual Report 2012–2013 93 Independent film projects IN NUMBERS supported by the NFB (FAP and ACIC) 76 Original NFB films and 135 co-productions Awards 8 491 New productions on Interactive websites NFB.ca/ONF.ca 83 33,721 Digital documents supporting DVD units (and other products) interactive works sold in Canada * 7,957 2 Public installations Public and private screenings at the NFB mediatheques (Montreal and Toronto) and other community screenings 3 Applications for tablets 6,126 Television broadcasts in Canada * The NFB mediatheques were closed on September 1, 2012, and the public screening program was expanded. -

Database Aesthetics, Modular Storytelling, and the Intimate Small Worlds of Korsakow Documentaries 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Anna Wiehl Database aesthetics, modular storytelling, and the intimate small worlds of Korsakow documentaries 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3331 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wiehl, Anna: Database aesthetics, modular storytelling, and the intimate small worlds of Korsakow documentaries. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 5 (2016), Nr. 1, S. 177– 197. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3331. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://www.necsus-ejms.org/test/korsakow-documentaries/ Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org Database aesthetics, modular storytelling, and the intimate small worlds of Korsakow documentaries Anna Wiehl NECSUS 5 (1), Spring 2016: 177–197 URL: https://necsus-ejms.org/korsakow-documentaries Keywords: complexity, database narrative, digital documentary, non-linearity, relationality, small data Small – the alternative big? Within the context of digitalisation -

Ealthy High-Rise

H ealthy High-rise A Guide to Innovation in the Design and Construction of High-Rise Residential Buildings CMHC—Home to Canadians Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) is the Government of Canada’s national housing agency.We help Canadians gain access to a wide choice of quality, affordable homes. Our mortgage loan insurance program has helped many Canadians realize their dream of owning a home.We provide financial assistance to help Canadians most in need to gain access to safe, affordable housing.Through our research, we encourage innovation in housing design and technology, community planning, housing choice and finance.We also work in partnership with industry and other Team Canada members to sell Canadian products and expertise in foreign markets, thereby creating jobs for Canadians here at home. We offer a wide variety of information products to consumers and the housing industry to help them make informed purchasing and business decisions.With Canada’s most comprehensive selection of information about housing and homes, we are Canada’s largest publisher of housing information. In everything that we do, we are helping to improve the quality of life for Canadians in communities across this country.We are helping Canadians live in safe, secure homes. CMHC is home to Canadians. Canadians can easily access our information through retail outlets and CMHC’s regional offices. You can also reach us by phone at 1 800 668-2642 (outside Canada call (613) 748-2003) By fax at 1 800 245-9274 (outside Canada (613) 748-2016) To reach us online, visit our home page at www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation supports the Government of Canada policy on access to information for people with disabilities. -

Interactive Project Proposals: the Early Stages

Working With the NFB’s Digital Studio June 2015 Working With the NFB’s Digital Studio As a unique creative and cultural laboratory, The NFB is eager to explore what it means to “create” and “connect” with Canadians in the age of technology. We are looking to work with a wide range of Canadian artists and media-makers interested in experimenting with the creative application of platforms and technology to story and form. Filmmakers, Interactive Designers, Photographers, Social Media Producers, Graphic Artists, Information Architects, Writers, Video and Sound Artists, Musicians, etc. We are excited by the collaborative nature of media today and are open to receiving project proposals from all types of artists and creators. What Kinds of Creations? As a public producer we have a duty to contribute to the ongoing social discourse of the day through the production of creative audiovisual works. We remain convinced of the powerful and transformative effects of art and imagination for the public good. We have a strong code of ethics that guides our work including the importance of an artistic voice and a diversity of voices, authenticity and creative excellence, innovation and risk taking, social relevance and the promotion of a civic, inclusive democratic culture. Our approach to story is innovative, open-ended, and participatory. We strive to create groundbreaking works that harness the appropriate technologies for each story and/or audience group, and contain built-in channels that open the project up for direct engagement. We are currently looking to produce new works that help us achieve our mission including interactive documentaries, mobile and locative media, interactive animations, photographic art and essays, data visualizations, physical installations, community media, interactive video, user- generated media, etc. -

Seventy Years of American Youth Hostels

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2003 Preservation for the People: Seventy Years of American Youth Hostels Elisabeth Dubin University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Dubin, Elisabeth, "Preservation for the People: Seventy Years of American Youth Hostels" (2003). Theses (Historic Preservation). 506. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/506 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Dubin, Elisabeth (2003). Preservation for the People: Seventy Years of American Youth Hostels. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/506 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preservation for the People: Seventy Years of American Youth Hostels Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Dubin, Elisabeth (2003). Preservation for the People: Seventy Years of American Youth Hostels. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/506 UNIVERSITYy* PENNSYLVANIA. UBKARIES PRESERVATION FOR THE PEOPLE: SEVENTY YEARS OF AMERICAN YOUTH HOSTELS Elisabeth Dubin A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of PennsyK'ania in Partial FuUillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2003 .g/V..— '^^^..oo^N.^::^^^^^^ John Milner, FAIA Samuel Y. Hams, PE, FAIA Adjunct Professor of Architecture Adjunct Professor of Architecture Tliesis Supervisor Reader ^<,,^;S>l^^'">^^*- Frank G. -

Connecting Present Moments and Present Eras with Interactive Documentary Ella Harris

Connecting Present Moments and Present Eras with Interactive Documentary Ella Harris To cite this version: Ella Harris. Connecting Present Moments and Present Eras with Interactive Documentary. Media Theory, Media Theory, 2020, Mediating Presents, 4 (2), pp.85-114. hal-03266383 HAL Id: hal-03266383 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03266383 Submitted on 21 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Special Issue: Mediating Presents Connecting Present Moments Media Theory Vol. 4 | No. 2 | 85-114 © The Author(s) 2020 and Present Eras with CC-BY-NC-ND http://mediatheoryjournal.org/ Interactive Documentary ELLA HARRIS Birkbeck, University of London, UK Abstract Interactive documentary is a non-linear digital form of documentary that allows users numerous pathways through multimedia content. This was the original meaning behind the abbreviation i-docs (Aston and Gaudenzi, 2012) and the sense in which I use the term. While in recent years the „i‟ has expanded to include immersion, my focus remains on interactivity and nonlinearity. The nonlinearity and multimodality of i-docs are being taken forward into experiments with i-docs as an academic method, including my own. -

No Classes, University Open) Oct

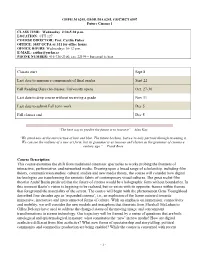

GS/FILM 6245, GS/HUMA 6245, GS/CMCT 6507 Future Cinema 1 CLASS TIME: Wednesday 2:30-5:30 p.m. LOCATION: CFT 127 COURSE DIRECTOR: Prof. Caitlin Fisher OFFICE: 303F GCFA or 311 for office hours OFFICE HOURS: Wednesdays 10-12 p.m. E-MAIL: [email protected] PHONE NUMBER: 416-736-2100, ext. 22199 – but email is best Classes start Sept 8 Last date to announce components of final grades Sept 22 Fall Reading Days (no classes, University open) Oct. 27-30 Last date to drop course without receiving a grade Nov 11 Last date to submit Fall term work Dec 5 Fall classes end Dec 5 “The best way to predict the future is to invent it” – Alan Kay “We stand now at the intersection of lure and blur. The future beckons, but we’re only partway through inventing it. We can see the outlines of a new art form, but its grammar is as tenuous and elusive as the grammar of cinema a century ago.” – Frank Rose Course Description This course examines the shift from traditional cinematic spectacles to works probing the frontiers of interactive, performative, and networked media. Drawing upon a broad range of scholarship, including film theory, communication studies, cultural studies and new media theory, the course will consider how digital technologies are transforming the semiotic fabric of contemporary visual cultures. The great realist film theorist André Bazin predicted that the future of cinema would be a holographic form without boundaries. In this moment Bazin’s vision is begining to be realized, but co-exists with its opposite: frames within frames that foreground the materiality of the screen.