Seventy Years of American Youth Hostels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Complaints Probate / Guardian / Family Court Victims

From the Desk of: Eliot Ivan Bernstein Inventor [email protected] www.iviewit.tv Direct Dial: (561) 245-8588 (o) (561) 886-7628 (c) Sent Via: Email and US Certified Mail Saturday, April 9, 2016 U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 202-514-2000 [email protected] [email protected] RE: CRIMINAL COMPLAINTS PROBATE / GUARDIAN / FAMILY COURT VICTIMS ORGANIZATIONS SUPPORTING THIS COMPLAINT 1. Americans Against Abusive Probate Guardianship Spokesperson: Dr. Sam Sugar PO Box 800511 Aventura, FL 33280 (855) 913 5337 By email: [email protected] On Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Americans-Against-Abusive-Probate- Guardianship/229316093915489 On Twitter: https://twitter.com/helpaaapg 2. Families Against Court Travesties, Inc. Spokesperson: Natalie Andre Focusing on issues concerning child custody and abuse of the family court system, our vision is that the best interest of the child prevails in family court. facebook.com/FamiliesAgainstCourtTravesties Letter Page 1of 12 Saturday, April 9, 2016 United States Attorney General Loretta Lynch Page 2 CRIMINAL COMPLAINTS PROBATE / GUARDIAN / Saturday, April 9, 2016 FAMILY COURT VICTIMS [email protected] (800) 201-5560 3. VoteFamily.Us Spokesperson: Mario A. Jimenez Jerez, M.D., B.S.E.E. (786) 253-8158 [email protected] http://www.votefamily.us/dr-mario-jimenez-in-senate-district-37 List of Victims @ http://www.jotform.com/grid/60717016674052 Dear Honorable US Attorney General Loretta Lynch: This is a formal CRIMINAL COMPLAINT to Loretta Lynch on behalf of multiple victims of crimes being committed by Judges, Attorneys and Guardians (All Officers of the Court) primarily in the Palm Beach County, FL. -

Legal Status of California Monarchs

The Legal Status of Monarch Butterflies in California International Environmental Law Project 2012 IELP Report on Monarch Legal Status The International Environmental Law Project (IELP) is a legal clinic at Lewis & Clark Law School that works to develop, implement, and enforce international environmental law. It works on a range of issues, including wildlife conservation, climate change, and issues relating to trade and the environment. This report was written by the following people from the Lewis & Clark Law School: Jennifer Amiott, Mikio Hisamatsu, Erica Lyman, Steve Moe, Toby McCartt, Jen Smith, Emily Stein, and Chris Wold. Biological information was reviewed by the following individuals from The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation: Carly Voight, Sarina Jepsen, and Scott Hoffman Black. This report was funded by the Monarch Joint Venture and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. For more information, contact: Chris Wold Associate Professor of Law & Director International Environmental Law Project Lewis & Clark Law School 10015 SW Terwilliger Blvd Portland, OR 97219 USA TEL +1-503-768-6734 FX +1-503-768-6671 E-mail: [email protected] Web: law.lclark.edu/org/ielp Copyright © 2012 International Environmental Law Project and the Xerces Society Photo of overwintering monarchs (Danaus plexippus) clustering on a coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) on front cover by Carly Voight, The Xerces Society. IELP Report on Monarch Legal Status Table of Contents Executive Summary .........................................................................................................................v I. Introduction .........................................................................................................................1 II. Regulatory Authority of the California Department of Fish and Game ..............................5 III. Protection for Monarchs in California State Parks and on Other State Lands .....................6 A. Management of California State Parks ....................................................................6 1. -

Amsterdam, 21 January 2009

Amsterdam, 17 October 2013 Announcement of partnership with Hostelling International Dear ISIC issuers, We are very pleased to announce that a global Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) has been signed between the International Student Identity Card (ISIC) Association and Hostelling International (HI). In fact, this MoU is the renewal of our partnership dating back to 1993. The objective of this MoU between the ISIC Association and Hostelling International is to outline joint opportunities for areas to work together on a local level, and to introduce a cobranded HI-ISIC card as a possible Hostelling International membership card where appropriate locally. Through the contact list attached to the MoU, we encourage you to connect with Hostelling International on a country level in order to explore the potential relationship and/or co-brand opportunities. Hostelling International will today also be announcing the partnership with the ISIC Association to their local member organisations. About Hostelling International Hostelling International is a non-governmental, not-for-profit organisation representing 70 Member Associations and Associate Organisations all over the world. Hostelling International works closely with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Hostelling International has also been identified as the sixth largest provider of travel accommodation in the world. Membership With nearly four million guest members, HI is one of the world’s largest youth membership organisations and is the only global network of Youth Hostel Associations. Customers can choose from around 3,700 Youth Hostels, all meeting internationally agreed standards in order to guarantee guest a safe and friendly place to stay. -

3.1 Tourism in Iceland

The Role of the Accommodation Sector in Sustainable Tourism Case Study from Iceland Emilia Prodea Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences University of Iceland 2016 The role of the accommodation sector in sustainable tourism Case Study from Iceland Emilia Prodea 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Environment and Natural Resources Advisors Dr. Rannveig Ólafsdóttir Dr. Lára Jóhannsdóttir Faculty Representative Hrönn Hrafnsdóttir Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Reykjavík, February 2016 The role of the accommodation sector in sustainable tourism. Case Study from Iceland 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Environment and Natural Resources Copyright © 2016 Emilia Prodea All rights reserved Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Askja, Sturlugata 7 101 Reykjavík Iceland Telephone: 525 4000 Bibliographic information: Emilia Prodea, 2016, The role of the accommodation sector in sustainable tourism. Case Study from Iceland, Master’s thesis, Programme of Environment and Natural Resources, Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Iceland, pp. 103. Printing: Háskólaprent ehf Reykjavík, Iceland, February 2016 Abstract The tourism industry is one of the world’s most significant sources of economic outcomes and employment, and also a significant contributor to climate change. The accommodation sector is the fundamental component of tourism and is responsible for approximately 21% of the tourism-related CO2 emissions. As a core tourism sector in the ecosystem services, accommodation establishments interfere with all types of tourism-related forms and concepts. -

Travel Leaders Echo Experts: Make Fact-Based Decisions About Traveling U.S

Travel Leaders Echo Experts: Make Fact-Based Decisions About Traveling U.S. Officials: "It Is Safe for Healthy Americans to Travel" WASHINGTON (March 10, 2020)—A coalition of 150 travel-related organizations issued the following statement on the latest developments around coronavirus (signatories below): "For the travel and hospitality industry, the safety of the traveling public, our guests and our employees is of the utmost importance. We are in daily contact with public health authorities and are acting on the most up-to-date information on the evolving coronavirus situation. "Health and government officials have continually assured the public that healthy Americans can 'confidently travel in this country.' While it's critically important to remain vigilant and take useful precautions in times like these, it's equally important to make calm, rational, and fact- based decisions. "Though the headlines may be worrisome, experts continue to say the overall coronavirus risk in the U.S. remains low. At-risk groups are older individuals and those with underlying health conditions, who should take extra precautions. "The latest expert guidance indicates that for the overwhelming majority, it's OK to live, work, play and travel in the U.S. By seeking and heeding the latest expert guidance—which includes vigorous use of good health practices, similar to the preventive steps recommended for the seasonal flu—America's communities will stay strong and continue to thrive. The decision to cancel travel and events has a trickle-down effect that threatens to harm the U.S. economy, from locally owned hotels, restaurants, travel advisors and tour operators to the service and frontline employees who make up the backbone of the travel industry and the American economy. -

HSBC Bank UK Pensioners' Association

HSBC Bank UK Pensioners’ Association Pensioner and Old Age Concessions and Discounts Contents Pensioner and Old Age Concessions and Discounts ............................................................... 1 Concessions and Discounts................................................................................................ 1 Dining ............................................................................................................................... 2 Sightseeing (prices may have changed) ............................................................................. 2 Museums, Arts & Entertainment ....................................................................................... 2 Travel & Leisure ............................................................................................................... 2 DIY & Gardening .............................................................................................................. 3 Local Authority Services ................................................................................................... 3 Miscellaneous ................................................................................................................... 4 Over-75s ........................................................................................................................... 4 PC Skills ........................................................................................................................... 4 Other Sites of Interest ....................................................................................................... -

2020 Pacific Coast Winter Window Survey Results

2020 Winter Window Survey for Snowy Plovers on U.S. Pacific Coast with 2013-2020 Results for Comparison. Note: blanks indicate no survey was conducted. REGION SITE OWNER 2017 2018 2019 2020 2020 Date Primary Observer(s) Gray's Harbor Copalis Spit State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum Conner Creek State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Damon Point WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Oyhut Spit WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Ocean Shores to Ocean City 4 10 0 9 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis County Total 4 10 0 9 Pacific Midway Beach Private, State Parks 22 28 58 66 27-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Graveyard Spit Shoalwater Indian Tribe 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum, R. Ashley Leadbetter Point NWR USFWS, State Parks 34 3 15 0 11-Feb W. Ritchie South Long Beach Private 6 0 7 0 10-Feb W. Ritchie Benson Beach State Parks 0 0 0 0 20-Jan W. Ritchie County Total 62 31 80 66 Washington Total 66 41 80 75 Clatsop Fort Stevens State Park (Clatsop Spit) ACOE, OPRD 10 19 21 20-Jan T. Pyle, D. Osis DeLaura Beach OPRD No survey Camp Rilea DOD 0 0 0 No survey Sunset Beach OPRD 0 No survey Del Rio Beach OPRD 0 No survey Necanicum Spit OPRD 0 0 0 20-Jan J. Everett, S. Everett Gearhart Beach OPRD 0 No survey Columbia R-Necanicum R. OPRD No survey County Total 0 10 19 21 Tillamook Nehalem Spit OPRD 0 17 26 19-Jan D. -

THE CHRISTMAS TRUCE PROJECT Introduction

THE CHRISTMAS TRUCE and Flanders Peace Field Project Don Mullan Concept “... a moment of humanity in a time of carnage... what must be the most extraordinary celebration of Christmas since those notable goings-on in Bethlehem.” - Piers Brendon, British Historian Contents Introduction 4 The Vision 8 Local Partners 9 The Projects: 9 1. Sport for Development and Peace (The Flanders Peace Field) 9 2. Culture 10 3. Cultural Patrimony 11 4. Major Symbolic Events 12 5. The Fans World Cup 13 Visitors, Tourists and Pilgrims 14 Investment Required and Local Body to Manage Development 15 The Flanders Peace Field 16 Voices from the Christmas Truce 18 Summary Biography of Presenter 20 THE CHRISTMAS TRUCE PROJECT Introduction The First World War - “The War to End All Wars” – lasted four years. It consumed the lives of an estimated 18 million people – thirteen thousand per day! Yet, there was one day, Christmas Day 1914, when the madness stopped and a brief peace, inspired by the Christmas story, broke out along the Western Front. The Island of Ireland Peace Park, Messines, Belgium, stands on a gentle slope overlooking the site of one of the most extraordinary events of World War I and, indeed, world history. German soldiers had been sent thousands of small Christmas trees and candles from back home. As night enveloped an unusually still and silent Christmas Eve, a soldier placed one of the candlelit trees upon the parapet of his trench. Others followed and before long a chain of flickering lights spread for miles along the German line. British and French soldiers observed in amazement. -

COUNCIL Agenda

ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda For the Meeting of January 24, 2018 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College 1. Opening Prayer 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Approval of the November 22, 2017 Minutes 4. Business arising from the Minutes 5. New Business a) Set the budget parameters for the upcoming fiscal year b) Bequest from the estate of Dorothy May Hayward c) Appointment of Architectural firm to design the new residence d) Approval of the Sketch Design Offer of Services for the new residence e) Development Committee f) Call for Honorary Degree Nominations 6. Reports from Committees, College Officers and Student Council a) Reports from Committees – Council Executive, Development, Finance & Admin. b) Report from Assembly c) Reports from College Officers and Student Council i) Warden ii) Dean of Studies iii) Development Office iv) Dean of Residence v) Spiritual Advisor vi) Bursar vii) Registrar viii) Senior Stick 7. Other Business 8. Adjournment ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL MINUTES For the Meeting of November 22, 2017 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 Room 108, St John’s College Present: D. Watt, G. Bak, P. Cloutier (Chair), J. McConnell, H. Richardson, J. Ripley, J. Markstrom, I. Froese, P. Brass, C. Trott, C. Loewen, J. James, S. Peters (Secretary) Regrets: D. Phillips, B. Pope, A. Braid, E. Jones, E. Alexandrin 1. Opening Prayer C. Trott opened the meeting with prayer. 2. Approval of the Agenda MOTION: That the agenda be approved as distributed. D. Watt / J. McConnell CARRIED 3. Approval of the September 27, 2017 Minutes MOTION: That the minutes of the meeting of September 27, 2017 be approved as distributed. -

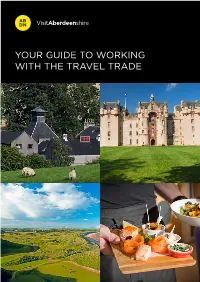

Your Guide to Working with the Travel Trade

YOUR GUIDE TO WORKING WITH THE TRAVEL TRADE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The travel trade – intermediaries such as tour Introduction 2 operators, wholesalers, travel agents and online travel agents - play a significant role in attracting What is the 3 visitors to Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire, even Travel Trade? though consumers are increasingly organising and planning their own trips directly. Working Attracting 5 with the travel trade is an effective and valuable way of reaching larger numbers of potential International travellers in global markets. Attention Attracting visitors to your business requires Understanding Your 9 some specialist industry awareness and an Target Markets understanding of all the different kinds of travel trade activity. It’s important to know Working with the 10 how the sector works from a business point Travel Trade of view, for example, the commission system, so that tourism products can be priced Rates and Commission 13 accordingly. Developing your offer to the required standard needs an understanding of Creating a Travel 14 different travel styles, language, cultural and culinary considerations and so on. Trade Sales Kit VisitAberdeenshire runs a comprehensive Hosting 16 programme of travel trade activities which Familiarisation Visits include establishing strong relationships with key operators to attract group and Steps to working 17 independent travel to our region. with the travel trade This guide aims to provide a straightforward introduction to the opportunities available Building Relationships 17 to Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire’s tourism businesses, enabling you to grow your Next Steps? 18 business through working with the national and international travel trade. Useful Web Sites 20 KEY TAKEAWAY............... The travel trade is often thought about for the group market only, but in fact the travel trade is also used extensively for small group and individual travel. -

Introduction to Hostelling International

Information & Application Form May 2007 INTRODUCTION TO HOSTELLING INTERNATIONAL The Youth Hostel movement was founded in Germany in the early years of this century, and spread rapidly between the wars, especially in Europe. Today, Hostelling International offers you a choice of nearly 4,500 accommodation centres in more than 60 countries worldwide. In Malaysia, the Malaysian Youth Hostels Association - MYHA was formed in the early fifties. The MYHA offers two accommodation centres in Malaysia at Kuala Lumpur & Penang which are associate hostels. Kuala Lumpur: Wira Hotel (Associate Youth Hostel) 123, Jalan Thamboosamy off Jalan Putra 5035 Kuala Lumpur. Tel: 03-4042 3333 Penang: Naza Hostel (Associate Youth Hostel) 555, Jalan CM Hashim Tanjung Tokong 11200 Penang Tel: 04-8909300 NO AGE LIMIT Despite their name, hostels are open to people of all ages in virtually every country where they are located. Only a small number of hostels in Germany have an age restriction which is a requirement of the local legislation. Guests under 14 years of age should be accompanied by an adult. MEMBERSHIP To stay at a hostel, you MUST become a member of your National Youth Hostel Association (YHA). In Malaysia, you can become a member of the MYHA in order to access to the hostels all over the world at an affordable price. PRIVILEGES OF BEING A MEMBER OF THE YHA You can stay at any one of the 4500 hostels worldwide at an affordable price now that you are a member of the YHA. You also get the privilege to certain benefits including access to discounts worldwide. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map