Tidal Marsh Invertebrates of Connecticut Nancy C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Freeze Tolerance in a Historically Tropical Snail Alice B

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 The evolution of freeze tolerance in a historically tropical snail Alice B. Dennis Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Dennis, Alice B., "The ve olution of freeze tolerance in a historically tropical snail" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1003. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1003 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF FREEZE TOLERANCE IN A HISTORICALLY TROPICAL SNAIL A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Alice B. Dennis B.S., University of California, Davis 2003 May, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who have helped make this dissertation possible. I would first like to thank my advisor, Michael E. Hellberg, for his support and guidance. Comments and discussion with my committee: Drs. Sibel Bargu Ates, Robb T. Brumfield, Kenneth M. Brown, and William B. Stickle, have been very helpful throughout the development of this project. I would also like to thank those whose guidance helped lead me down this path, particularly Rick Grosberg, John P. Wares and Alex C. C. Wilson. -

Panama and Costa Rica*

NEW SPECIES OF GRAMMONOTA (ARANEAE, LINYPHIIDAE) FROM PANAMA AND COSTA RICA* BY ARTHUR IV[. CHICKERING Museum of Comparative Zoology Numerous species of the genus Grammonota Emerton, I882, have been recognized trom North and Central America as far south as Costa Rica. Two species of this genus were reported from Costa Rica by Bishop and Crosby in 1932. Kraus (955) did not report this genus from E1 Salvador, and it has not been reported from Panama as far as I have. been able to determine. Many specimens belonging to this genus have appeared in my collections from Panama during the. past forty years and the present seems to be a convenient time to put these on record. The frequency with which members of this genus have appeared in my collections from Panama indicates, I believe, the need for more careful collecting throughout the Neo- tropical region. Grants GB-ISOI and GB-5oI3 from the National Science Founda- tion have turnished aid for several collecting trips in Central Amer- ica, the West Indies and Florida together with my continued research in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, for nearly five and one half year.s. As I have so frequently done in the past, I am again acknowledging the very gracious help and encour- agement received from members of the staff of the Museum of Com- parative Zoology extending over a period of many years. Genus Grammonota Emerton, 1882 Grammonota tabuna sp. nov. Figures I- IO Holotype. The male holotype is from Gatun, Panama Canal Zone, January 30, 1958. The name of the species is an arbitrary combination of letters. -

List of Ohio Spiders

List of Ohio Spiders 2 August 2021 Richard A. Bradley Department of EEO Biology Ohio State University Museum of Biological Diversity 1315 Kinnear Road Columbus, OH 43212 This list is based on published specimen records of spider species from Ohio. Additional species that have been recorded during the Ohio Spider Survey (beginning 1994) are also included. I would very much appreciate any corrections; please mail them to the above address or email ([email protected]). 676 [+6] Species Mygalomorphae Antrodiaetidae (foldingdoor spiders) (2) Antrodiaetus robustus (Simon, 1890) Antrodiaetus unicolor (Hentz, 1842) Atypidae (purseweb spiders) (3) Sphodros coylei Gertsch & Platnick, 1980 Sphodros niger (Hentz, 1842) Sphodros rufipes (Latreille, 1829) Euctenizidae (waferdoor spiders) (1) Myrmekiaphila foliata Atkinson, 1886 Halonoproctidae (trapdoor spiders) (1) Ummidia audouini (Lucas, 1835) Araneomorphae Agelenidae (funnel weavers) (14) Agelenopsis emertoni Chamberlin & Ivie, 1935 | Agelenopsis kastoni Chamberlin & Ivie, 1941 | Agelenopsis naevia (Walckenaer, 1805) grass spiders Agelenopsis pennsylvanica (C.L. Koch, 1843) | Agelnopsis potteri (Blackwell, 1846) | Agelenopsis utahana (Chamberlin & Ivie, 1933) | Coras aerialis Muma, 1946 Coras juvenilis (Keyserling, 1881) Coras lamellosus (Keyserling, 1887) Coras medicinalis (Hentz, 1821) Coras montanus (Emerton, 1889) Tegenaria domestica (Clerck, 1757) barn funnel weaver In Wadotes calcaratus (Keyserling, 1887) Wadotes hybridus (Emerton, 1889) Amaurobiidae (hackledmesh weavers) (2) Amaurobius -

Pedipedinae (Gastropoda: Ellobiidae) from Hong Kong

The marine flora and fauna of Hong Kong and southern China III (ed. B. Morton). Proceedings of the Fourth International Marine Biological Workshop: The Marine Flora and Fauna of Hong Kong and Southern China, Hong Kong, 11-29 April 1989. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1992. PEDIPEDINAE (GASTROPODA: ELLOBIIDAE) FROM HONG KONG Ant6nio M. de Frias Martins Departamento de Biologia, Universidade dos A~ores,P-9502 Ponta Delgada, Siio Miguel, A~ores,Portugal ABSTRACT Two species of Pedipedinae are recorded for the first time from Hong Kong and are here provisionally referred to as Pedipes jouani Montrouzier, 1862 and Microtralia alba (Gassies, 1865), described from New Caledonia. A descriptive study of the reproductive and nervous systems was conducted and confirms previous studies that both genera are consubfamilial. The distribution and dispersal of the species is discussed. INTRODUCTION The Indo-Pacific Ellobiidae are particularly well represented by conspicuous, mangrove- dwelling, macroscopic species, relatively few of which have been studied anatomically. Koslowsky (1933) presented a detailed description of Melampus boholensis 'H. and A. Adams' Pfeiffer, 1856. Morton (1955) described the anatomy of Pythia Roding, 1798, Ellobium Roding, 1798 [E.aurisjudae (L. 1758)l and of the small pedipedinian Marinula King, 1832 [M.filholi Hutton, 18781. Knipper and Meyer (1956) provided good illus- trations of the nervous systems of Ellobium (Auriculodes) gaziensis (Preston, 1913), Cassidula labrella (Deshayes, 1830) and Melampus semisulcatus Mousson, 1869. Cassidula Fhssac, 1821, Ellobium and Pythia were discussed by Beny et al. (1967) and Sumikawa and Miura (1978) studied in detail the reproductive system of Ellobium chinense (Pfeiffer, 1854). -

Arboreal Spiders (Araneae) on Balsam Fir and Spruces I N East-Central Maine

Jennings, D . T. and J. B. Dimond. 1988. Arboreal spiders (Araneae) on balsam fir and spruces i n East-Central Maine . J. Arachnol ., 16:223-235 . ARBOREAL SPIDERS (ARANEAE) ON BALSAM FIR AND SPRUCES IN EAST-CENTRAL MAIN E Daniel T. Jennings Northeastern Forest Experiment Statio n USDA Building, University of Maine Orono, Maine 04469 USA and John B. Dimond Department of Entomology University of Maine Orono, Maine 04469 USA ABSTRACT Spiders of 11 families, 22 genera, and at least 33 species were collected from crown foliage samples of Abies balsamea (L .) Mill., Picea rubens Sarg., and Picea glauca (Moench) Voss in east-central Maine. For both study years (1985, 1986), spider species composition varied by foraging strategy (we b spinner, hunter) and among 10 study sites . Numbers, life stages, and sex ratios of spiders also differe d between study years. Spider densities per m 2 of foliage area generally were greater (P 0 .05) o n spruces Cit. = 16.3 ± 1 .1) than on fir (X = 10.9 ± 1 .0). Estimates of absolute populations of arboreal spiders ranged from 35,139 to 323,080/ha ; of spruce budworm from 271,401 to 6,122,919/ha. Spider- budworm densities/ha covaried significantly (P 5 0.001) each year (r = 0.84, 1985 ; r = 0.71, 1986). None of the measured forest-stand parameters (basal area, tree species percentage) were reliabl e predictors of spider populations/ha . INTRODUCTION Recent devastating outbreaks of the spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumife- rana (Clem.), have renewed interest in determining potential natural enemies o f this defoliator of northeastern spruce-fir forests . -

The Spiders and Scorpions of the Santa Catalina Mountain Area, Arizona

The spiders and scorpions of the Santa Catalina Mountain Area, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Beatty, Joseph Albert, 1931- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 16:48:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551513 THE SPIDERS AND SCORPIONS OF THE SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAIN AREA, ARIZONA by Joseph A. Beatty < • • : r . ' ; : ■ v • 1 ■ - ' A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1961 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at the Uni versity of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for per mission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Reproductive Cycle and Embryonic Development of the Gastropod

Reproductive cycle and embryonic development of the gastropod Melampus coffeus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Ellobiidae) in the Brazilian Northeast Maia, RC.a*, Rocha-Barreira, CA.b and Coutinho, R.c aLaboratório de Ecologia de Manguezais, Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Ceará, Campus Acaraú, Av. Desembargador Armando de Sales Louzada, s/n, CEP 62580-000, Acaraú, CE, Brazil bLaboratório de Zoobentos, Instituto de Ciências do Mar, Universidade Federal do Ceará – UFC, Av. Abolição, 3207, Meireles, CEP 60165-081, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil cLaboratório de Bioincrustação e Ecologia Bêntica, Departamento de Oceanografia, Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira, Rua Kioto, 253, CEP 28930-000, Arraial do Cabo, RJ, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received October 3, 2011 – Accepted January 25, 2012 – Distributed November 30, 2012 (With 4 figures) Abstract Melampus coffeus belongs to a primitive group of pulmonate mollusks found mainly in the upper levels of the marine intertidal zone. They are common in the neotropical mangroves. Little is known about the biology of this species, particularly about its reproduction. The aim of this study was to 1) characterize the morphology and histology of M. coffeus´ gonad; 2) describe the main gametogenesis events and link them to a range of maturity stages; 3) chronologically evaluate the frequency of the different maturity stages and their relation to environmental factors such as water, air and sediment temperatures, relative humidity, salinity and rainfall; and 4) characterize M. coffeus´ spawning, eggs and newly hatched veliger larvae. Samples were collected monthly between February, 2007 and January, 2009 from the mangroves of Praia de Arpoeiras, Acaraú County, State of Ceará, northeastern Brazil. -

Guide to Common Tidal Marsh Invertebrates of the Northeastern

- J Mississippi Alabama Sea Grant Consortium MASGP - 79 - 004 Guide to Common Tidal Marsh Invertebrates of the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico by Richard W. Heard University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688 and Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, Ocean Springs, MS 39564* Illustrations by Linda B. Lutz This work is a result of research sponsored in part by the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, Office of Sea Grant, under Grant Nos. 04-S-MOl-92, NA79AA-D-00049, and NASIAA-D-00050, by the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Gram Consortium, by the University of South Alabama, by the Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, and by the Marine Environmental Sciences Consortium. The U.S. Government is authorized to produce and distribute reprints for govern mental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation that may appear hereon. • Present address. This Handbook is dedicated to WILL HOLMES friend and gentleman Copyright© 1982 by Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium and R. W. Heard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the author. CONTENTS PREFACE . ....... .... ......... .... Family Mysidae. .. .. .. .. .. 27 Order Tanaidacea (Tanaids) . ..... .. 28 INTRODUCTION ........................ Family Paratanaidae.. .. .. .. 29 SALTMARSH INVERTEBRATES. .. .. .. 3 Family Apseudidae . .. .. .. .. 30 Order Cumacea. .. .. .. .. 30 Phylum Cnidaria (=Coelenterata) .. .. .. .. 3 Family Nannasticidae. .. .. 31 Class Anthozoa. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Order Isopoda (Isopods) . .. .. .. 32 Family Edwardsiidae . .. .. .. .. 3 Family Anthuridae (Anthurids) . .. 32 Phylum Annelida (Annelids) . .. .. .. .. .. 3 Family Sphaeromidae (Sphaeromids) 32 Class Oligochaeta (Oligochaetes). .. .. .. 3 Family Munnidae . .. .. .. .. 34 Class Hirudinea (Leeches) . .. .. .. 4 Family Asellidae . .. .. .. .. 34 Class Polychaeta (polychaetes).. .. .. .. .. 4 Family Bopyridae . .. .. .. .. 35 Family Nereidae (Nereids). .. .. .. .. 4 Order Amphipoda (Amphipods) . ... 36 Family Pilargiidae (pilargiids). .. .. .. .. 6 Family Hyalidae . -

Noaa 13648 DS1.Pdf

r LOAI<CO Qpy N Guide to Gammon Tidal IVlarsh Invertebrates of the Northeastern Gulf of IVlexico by Richard W. Heard UniversityofSouth Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688 and CiulfCoast Research Laboratory, Ocean Springs, MS39564" Illustrations by rimed:tul""'"' ' "=tel' ""'Oo' OR" Iindu B. I utz URt,i',"::.:l'.'.;,',-'-.,":,':::.';..-'",r;»:.",'> i;."<l'IPUS Is,i<'<i":-' "l;~:», li I lb~'ab2 Thisv,ork isa resultofreseaich sponsored inpart by the U.S. Department ofCommerce, NOAA, Office ofSea Grant, underGrani Nos. 04 8 Mol 92,NA79AA D 00049,and NA81AA D 00050, bythe Mississippi Alabama SeaGrant Consortium, byche University ofSouth Alabama, bythe Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, andby the Marine EnvironmentalSciences Consortium. TheU.S. Government isauthorized toproduce anddistribute reprints forgovern- inentalpurposes notwithstanding anycopyright notation that may appear hereon. *Preseitt address. This Handbook is dedicated to WILL HOLMES friend and gentleman Copyright! 1982by Mississippi hlabama SeaGrant Consortium and R. W. Heard All rightsreserved. No part of thisbook may be reproduced in any manner without permissionfrom the author. Printed by Reinbold Lithographing& PrintingCo., BooneviBe,MS 38829. CONTENTS 27 PREFACE FamilyMysidae OrderTanaidacea Tanaids!,....... 28 INTRODUCTION FamilyParatanaidae........, .. 29 30 SALTMARSH INVERTEBRATES ., FamilyApseudidae,......,... Order Cumacea 30 PhylumCnidaria =Coelenterata!......, . FamilyNannasticidae......,... 31 32 Class Anthozoa OrderIsopoda Isopods! 32 Fainily Edwardsiidae. FamilyAnthuridae -

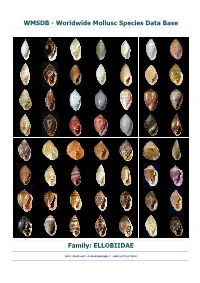

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: ELLOBIIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: HETEROBRANCHIA-PULMONATA-EUPULMONATA-ELLOBIOIDEA ------ Family: ELLOBIIDAE L. Pfeiffer, 1854 (Land) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=34, Subgenus=13, Species=287, Subspecies=12, Synonyms=334, Images=187 acteocinoides , Microtralia acteocinoides J.T. Kuroda & T. Habe, 1961 acuminata , Ovatella acuminata P.M.A. Morelet, 1889 - syn of: Myosotella myosotis (J.P.R. Draparnaud, 1801) acuta , Marinula acuta (D'Orbigny, 1835) acuta , Pythia acuta J.B. Hombron & C.H. Jacquinot, 1847 acutispira , Melampus acutispira W.H. Turton, 1932 - syn of: Melampus parvulus L. Pfeiffer, 1856 adamsianus , Melampus adamsianus L. Pfeiffer, 1855 adansonii , Pedipes adansonii H.M.D. de Blainville, 1824 - syn of: Pedipes pedipes (J.G. Bruguière, 1789) adriatica , Ovatella adriatica H.C. Küster, 1844 - syn of: Myosotella myosotis (J.P.R. Draparnaud, 1801) aegiatilis, Pythia pachyodon aegiatilis H.A. Pilsbry & Y. Hirase, 1908 aequalis , Ovatella aequalis (R.T. Lowe, 1832) afer , Pedipes afer J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Pedipes pedipes (J.G. Bruguière, 1789) affinis , Marinula affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 - syn of: Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 affinis , Laemodonta affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 - syn of: Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 affinis , Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 alba , Microtralia alba (J. Gassies, 1865) albescens , Ovatella albescens T.V. Wollaston, 1878 - syn of: Ovatella aequalis (R.T. Lowe, 1832) albovaricosa, Pythia albovaricosa L. Pfeiffer, 1853 albus , Melampus albus C.A. Davis, 1904 - syn of: Melampus monile (J.G. -

1 the RESTRUCTURING of ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS in RESPONSE to PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell a Dissertation Submitt

THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell 1 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Winter 2019 © Adam B. Mitchell All Rights Reserved THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell Approved: ______________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: ______________________________________________________ Mark W. Rieger, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: ______________________________________________________ Douglas J. Doren, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Charles R. Bartlett, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Jeffery J. Buler, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

List of Ohio Spiders

List of Ohio Spiders 20 March 2018 Richard A. Bradley Department of EEO Biology Ohio State University Museum of Biodiversity 1315 Kinnear Road Columbus, OH 43212 This list is based on published specimen records of spider species from Ohio. Additional species that have been recorded during the Ohio Spider Survey (beginning 1994) are also included. I would very much appreciate any corrections; please mail them to the above address or email ([email protected]). 656 [+5] Species Mygalomorphae Antrodiaetidae (foldingdoor spiders) (2) Antrodiaetus robustus (Simon, 1890) Antrodiaetus unicolor (Hentz, 1842) Atypidae (purseweb spiders) (3) Sphodros coylei Gertsch & Platnick, 1980 Sphodros niger (Hentz, 1842) Sphodros rufipes (Latreille, 1829) Ctenizidae (trapdoor spiders) (1) Ummidia audouini (Lucas, 1835) Araneomorphae Agelenidae (funnel weavers) (14) Agelenopsis emertoni Chamberlin & Ivie, 1935 | Agelenopsis kastoni Chamberlin & Ivie, 1941 | Agelenopsis naevia (Walckenaer, 1805) grass spiders Agelenopsis pennsylvanica (C.L. Koch, 1843) | Agelnopsis potteri (Blackwell, 1846) | Agelenopsis utahana (Chamberlin & Ivie, 1933) | Coras aerialis Muma, 1946 Coras juvenilis (Keyserling, 1881) Coras lamellosus (Keyserling, 1887) Coras medicinalis (Hentz, 1821) Coras montanus (Emerton, 1889) Tegenaria domestica (Clerck, 1757) barn funnel weaver In Wadotes calcaratus (Keyserling, 1887) Wadotes hybridus (Emerton, 1889) Amaurobiidae (hackledmesh weavers) (2) Amaurobius ferox (Walckenaer, 1830) In Callobius bennetti (Blackwall, 1848) Anyphaenidae (ghost spiders)