Creating Cayman As an Offshore Financial Center: Structure & Strategy Since 1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Author: Alicia E

ENTERTEXT Identity as Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Author: Alicia E. Ellis Source: EnterText, “Special Issue on Andrea Levy 9,” (2012): 69-83. Abstract Andrea Levy's Small Island (2004) presents a counter-history of the period before and after World War II (1939-1945) when men and women from the Caribbean volunteered for all branches of the British armed services and many eventually immigrated to London after the war officially ended in 1945. Her historical novel moves back and forth between 1924 and 1948 as well as across national borders and cultures. Levy’s novel, written more than fifty years after the first Windrush arrival, creates a common narrative of nation and identity in order to understand the experiences of Black people in Britain. Small Island—structured around four competing voices whose claims of textual, personal and historical truth must be acknowledged—refuses to establish a singular articulation of the experience of migration and empire. In this essay, I focus on discrete moments in the “Prologue” in Levy’s Small Island in order to think through the formation of discursive identity through the encounter with others and the necessity of accommodating difference. Small Island forecloses the possibility of addressing modern multiculturalism as a purported ‘happy ending’ in light of Levy’s formulation of the Windrush moment as disruptive, violent, and overwhelmed by flawed characters. Yet, through the space of writing, she also invites the reader to experience moments of encounter and negotiate the often competing claims on nationhood, citizenship, and culture. Identity as Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Alicia E. -

"Free Negroes" - the Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 12-16-2015 "Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670 Patrick John Nichols Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Nichols, Patrick John, ""Free Negroes" - The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655-1670." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/100 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FREE NEGROES” – THE DEVELOPMENT OF EARLY ENGLISH JAMAICA AND THE BIRTH OF JAMAICAN MAROON CONSCIOUSNESS, 1655-1670 by PATRICK JOHN NICHOLS Under the Direction of Harcourt Fuller, PhD ABSTRACT The English conquest of Jamaica in 1655 was a turning point in the history of Atlantic World colonialism. Conquest displaced the Spanish colony and its subjects, some of who fled into the mountainous interior of Jamaica and assumed lives in isolation. This project reconstructs the historical experiences of the “negro” populations of Spanish and English Jamaica, which included its “free black”, “mulattoes”, indigenous peoples, and others, and examines how English cosmopolitanism and distinct interactions laid the groundwork for and informed the syncretic identities and communities that emerged decades later. Upon the framework of English conquest within the West Indies, I explore the experiences of one such settlement alongside the early English colony of Jamaica to understand how a formal relationship materialized between the entities and how its course inflected the distinct socio-political identity and emergent political agency embodied by the Jamaican Maroons. -

Friday, March 19, 2021

Caymanian Thank You Page 8 Friday, March 19, 2021 Issue No 640 www.caymaniantimes.ky 50¢ HEATHER BODDEN Community PUBLIC MEETING Creates Saturday, 20 March, 7:00pm Jayson Avenue,Savannah Country INSIDE THIS ISSUE Cayman’s Coast Guard LOCAL NEWS — page 6 Ready for Service By Christopher Tobutt Sixteen young men and women made Cayman proud-as-can-be when they marched onto the lawn in front overlook- MISS CAYMAN VISITS THE BRAC ing Pedro Bluff and the diamond-shim- mering sea in their smart dark blue uni- forms and white maritime caps. They LOCAL NEWS — page 10 were making history as the very first Cay- man Islands Coast Guards. After their parade, Cayman’s newest uniformed agency took their seats in front of dignitaries including Premier, Hon Al- den McLaughlin, His Excellency the Gov- ernor Martyn Roper, and Deputy Governor Franz Manderson. In his welcome remarks, Master of Cer- emoniesSEE COASTGUARD Welcome READY remarks, FOR SERVICE,Mr. Winston Page 7 X H.E the Governor inspects the Coast Guard PREMIER CLARIFIES REMARKS BUT INSISTS ROAD PROJECT IS VITAL Government’s Performance Debated ARTS & CULTURE — page 12 For the first time in the Chamber of Commerce election forums candidates have been asked to rate the government’s performance. All of the independent candidates for Newlands - incumbent Alva Suck- oo, Wayne Panton, Raul Gonzalez Jr and Roydell Carter - gave the incumbent Peo- Rundown Returns to Spread ple’s Progressive Movement(PPM) Unity Laughter, Not COVID! X MP Alva Suckoo X Wayne Panton coalitionSEE GOVERNMENT’S good grades PERFORMANCE, for its economic Page 5 1 2 3 4 3' – 6' Let’s Keep Working Together Vaccine Protect yourself and your community against COVID-19. -

PELLIZZARI-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (3.679Mb)

A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Pellizzari, Peter. 2020. A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365752 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 A dissertation presented by Peter Pellizzari to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2020 © 2020 Peter Pellizzari All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: Jane Kamensky and Jill Lepore Peter Pellizzari A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 Abstract The American Revolution not only marked the end of Britain’s control over thirteen rebellious colonies, but also the beginning of a division among subsequent historians that has long shaped our understanding of British America. Some historians have emphasized a continental approach and believe research should look west, toward the people that inhabited places outside the traditional “thirteen colonies” that would become the United States, such as the Gulf Coast or the Great Lakes region. -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

Special Feature Section the CAYMAN ISLANDS New Leadership for New Challenges in the New Decade

MAGAZINE Special Feature Section THE CAYMAN ISLANDS New Leadership For New Challenges In the New Decade Special Feature Section MAGAZINE 62 G RAND C AYMAN HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR DUNCAN TAYLOR HONORABLE PREMIER W. M CKEEVA BUSH s the Cayman Islands enter a new era certain to encompass challenges, changes, and opportuni- ties, we at Grand Cayman Magazine want to Acongratulate our first-ever Premier, the Hon. W. McKeeva Bush, and welcome, publicly and warmly, our new Governor, His Excellency Duncan Taylor, his wife Marie-Beatrice, and their son Max. We trust they will very quickly find they are among new friends and well-wishers in these islands. In this special section, we will introduce you to Governor Taylor and his wife (a longer profile may appear in these pages after they get settled). We will also share with you an extensive profile on Premier Bush that tracks his trajectory from his humble West Bay beginnings to his current post as the most powerful leader in the history of the Cayman Islands. In addition to our editorial voices, companies and individuals have also stepped forward through our pages, and their messages of goodwill are included in this commemorative section. G RAND C AYMAN 63 PHOTO BY DAVID R. LEGGE BY DAVID PHOTO His Excellency the Governor Duncan Taylor participates in formal ceremonies following his swearing-in. 64 G RAND C AYMAN Special Profile GOVERNOR DUNCAN TAYLOR A Seasoned Diplomat Takes Over in Cayman hen Governor Duncan Taylor moved into his new home overlooking Seven Mile Beach this January, the transition W marked his 11th posting in a distinguished 27-year career with the British Foreign Service. -

Movement of the People: the Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-7-2008 Movement Of The eople:P The Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements, Race, and Class in the Caribbean Deborah G. Weeks University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Weeks, Deborah G., "Movement Of The eP ople: The Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements, Race, and Class in the Caribbean" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/560 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Movement Of The People: The Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements, Race, and Class in the Caribbean by Deborah G. Weeks A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Africana Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Deborah Plant, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Eric D. Duke, Ph.D. Navita Cummings James, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 7, 2008 Keywords: black power, colonization, independence, pride, nationalism, west indies © Copyright 2008 , Deborah G. Weeks Dedication I dedicate this thesis to the memory of Dr. Trevor Purcell, without whose motivation and encouragement, this work may never have been completed. I will always remember his calm reassurance, expressed confidence in me, and, of course, his soothing, melodic voice. -

Dangerous Spirit of Liberty: Slave Rebellion, Conspiracy, and the First Great Awakening, 1729-1746

Dangerous Spirit of Liberty: Slave Rebellion, Conspiracy, and the First Great Awakening, 1729-1746 by Justin James Pope B.A. in Philosophy and Political Science, May 2000, Eckerd College M.A. in History, May 2005, University of Cincinnati M.Phil. in History, May 2008, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by David J. Silverman Professor of History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Justin Pope has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2014. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Dangerous Spirit of Liberty: Slave Rebellion, Conspiracy, and the Great Awakening, 1729-1746 Justin Pope Dissertation Research Committee: David J. Silverman, Professor of History, Dissertation Director Denver Brunsman, Assistant Professor of History, Committee Member Greg L. Childs, Assistant Professor of History, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2014 by Justin Pope All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments I feel fortunate to thank the many friends and colleagues, institutions and universities that have helped me produce this dissertation. The considerable research for this project would not have been possible without the assistance of several organizations. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, the Maryland Historical Society, the Cosmos Club Foundation of Washington, D.C., the Andrew Mellon Fellowship of the Virginia Historical Society, the W. B. H. Dowse Fellowship of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Thompson Travel Grant from the George Washington University History Department, and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Fellowship all provided critical funding for my archival research. -

1 Regional Ministries of Foreign Affairs Anguilla

REGIONAL MINISTRIES OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS ANGUILLA Office of the Chief Minister Government Headquarters P. O. Box 60 The Valley ANGUILLA Tel. 01 264 497 2518 Fax. 01 264 497 3389 Email : [email protected] Chief Minister: Hon. Hubert HUGHES ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade New Government Office Complex Queen Elizabeth Highway St. John ANTIGUA, W.I. Tel. 01 268 462 1052 Fax. 01 268 462 2482 Email: [email protected] Foreign Minister: Hon. Charles Henry FERNANDEZ Independence Day: 01 November ARUBA Department of Foreign Affairs J.A. Irausquinplein 2A Oranjestad ARUBA Tel. 0 297 583 4705/0 297 582 4564 Fax. 02 97 583 4660 Email: [email protected] Foreign Minister: Hon. Michiel Godfred EMAN National Day: 18 March 1 BAHAMAS (COMMONWEALTH) Ministry of Foreign Affairs Goodmans Bay Corporate Centre West Bay St. P.O. Box No. 3746 Nassau, N.P. THE BAHAMAS Tel. 01 242 322 7624/5 Fax. 01 242 328 8212/326 2123 Email: [email protected] Protocol: Tel: 01 242 356 5956/7 Fax: 01 242 328 8212/326 2123 Foreign Minister: The Hon. Frederick A. MITCHELL Independence Day: 10 July BARBADOS Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade 1 Culloden Road St. Michael BARBADOS. W. I. BB 14018 Tel. 01 246 431 2200 Fax. 01 246 228 0838 Airport Fax: 01 246 429 6652 Email: [email protected] Foreign Minister: Senator the Hon. Maxine Mc CLEAN Independence Day: 30 November 2 BELIZE Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade 2nd Floor NEMO Building P. O. Box 174 Belmopan City Cayo District BELIZE, CENTRAL AMERICA Tel: 0 501 822 2322/2167 Fax. -

The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 the Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001

8 Philip Lynch The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 Philip Lynch As Conservatives reflected on the 1997 general election, they could agree that the issue of Britain’s relationship with the European Union (EU) was a significant factor in their defeat. But they disagreed over how and why ‘Europe’ had contributed to the party’s demise. Euro-sceptics blamed John Major’s European policy. For Euro-sceptics, Major had accepted develop- ments in the European Union that ran counter to the Thatcherite defence of the nation state and promotion of the free market by signing the Maastricht Treaty. This opened a schism in the Conservative Party that Major exacer- bated by paying insufficient attention to the growth of Euro-sceptic sentiment. Membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) prolonged recession and undermined the party’s reputation for economic competence. Finally, Euro-sceptics argued that Major’s unwillingness to rule out British entry into the single currency for at least the next Parliament left the party unable to capitalise on the Euro-scepticism that prevailed in the electorate. Pro-Europeans and Major loyalists saw things differently. They believed that Major had acted in the national interest at Maastricht by signing a Treaty that allowed Britain to influence the development of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) without being bound to join it. Pro-Europeans noted that Thatcher had agreed to an equivalent, if not greater, loss of sovereignty by signing the Single European Act. They believed that much of the party could and should have united around Major’s ‘wait and see’ policy on EMU entry. -

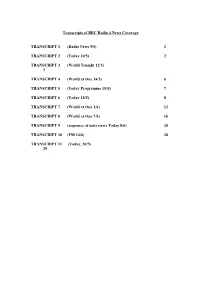

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 2 (Today 10/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 3 (World Tonight 12/5) 3 TRANSCRIPT 4 (World at One 14/5) 6 TRANSCRIPT 5 (Today Programme 15/5) 7 TRANSCRIPT 6 (Today 18/5) 8 TRANSCRIPT 7 (World at One 1/6) 12 TRANSCRIPT 8 (World at One 7/6) 16 TRANSCRIPT 9 (sequence of interviews Today 8/6) 20 TRANSCRIPT 10 (PM 14/6) 28 TRANSCRIPT 11 (Today, 20/5) 29 RADIO TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) James Cox: William Hague has dismissed the breakaway Pro-Europe Conservatives as fanatics after a claim that next month’s European elections will finish him off as the Tory leader. The leader of the rebel group John Stevens said that despite Tory successes in the local council elections, the party’s split over Europe would see its share of the vote fall to around 25% in next month’s poll. But Mr Hague, interviewed by David Frost, thoroughly rejected the claims. Nicholas Jones reports. Nicholas Jones: The Conservatives knew that they could hardly fail to make significant gains in last week’s council elections. But because of the party’s continuing feud over Europe, the Tories’ chances of a continued recovery in next month’s European elections are clouded in uncertainty. The pro-European Conservatives’ leader, John Stevens, said William Hague was mad to have ruled out British membership of the Euro as far ahead as the next Parliament. He predicted that the Tory vote would drop to 25% and that it would be the end of Mr Hague. -

An Enquiry Into the Abolition of the Inner London Education Authority (1964 to 1988), with Particular Reference to Politics and Policy Making

University of Bath PHD An enquiry into the abolition of the Inner London Education Authority (1964-1988): with particular reference to politics and policy making Radford, Alan Award date: 2009 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 An Enquiry into the Abolition of the Inner London Education Authority (1964 to 1988), with Particular Reference To Politics and Policy Making Alan Radford A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD University of Bath Department of Education June 2009 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. A copy of this thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author.