M. Jazbec: Individualism As a Determinant of Successful Diplomats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Book

MINISTRY MINISTRY OF EDUCATION OF FINANCE MALTESE OLYMPIC COMMITTEE MALTA SPORTS COUNCIL TH 100 ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS PROGRAMME 31st JANUARY 2008 ARRIVAL OF DELEGATIONS 1st FEBRUARY 2008 18.30 hrs THANKSGIVING MASS at ATTARD PARISH CHURCH 19.45 hrs RECEPTION at ATTARD PARISH HALL 2nd FEBRUARY 2008 20.00 hrs 100th ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION DINNER at Suncrest Hotel . SHOOTING PROGRAMME Bidnija B’Bugia Qormi Range A Range B Fri. 01-Feb Skeet - training Double Trap - training Trap - training Trap - training Sat. 02-Feb Skeet - training Double Trap - Off. training Trap - training Trap - training Sun. 03-Feb Skeet - training Double Trap - Comp & Final Trap - training Trap - training Mon. 04-Feb Skeet - Off. training Trap - training Trap - training Trap - training Tues. 05-Feb Skeet - Comp 75 targets Trap - training Trap - training Trap - training Wed. 06-Feb Skeet - Trap - training Trap - training Trap - training Comp 50 targets & Final Thur. 07-Feb Trap - Off. training Trap - Off. training Trap - Trap - Off. Training Off. Training Fri. 08-Feb Trap - Trap - Comp 25 targets Comp 25 targets Sat. 09-Feb Trap - Trap - Comp 25 targets Comp 25 targets Sun. 10-Feb Trap - Trap - Comp 25 targets & Final Comp 25 targets 11th FEBRUARY 2008 DEPARTURE OF DELEGATIONS A Century of Shooting Sport in Malta 1 Message from the President & Secretary General of the MSSF It is with great pleasure that we have to express our thoughts on the achievement of this mile stone by the Malta Shooting Sport Federation. Very few other local associations th have preceded our federation in celebrating their 100 Anniversary of organized sport. It all started in 1908 as the Malta Shooting Club, when the pioneers of our beloved sport organized shooting competitions on their premises in Attard. -

Slovenia: Mature, Self-Confident, Lively, Modern, Brave, Developing and Optimistic

SPORTS TWENTY-FIVE YEARS Slovenia: mature, self-confident, lively, modern, brave, developing and optimistic If some things seemed beyond our reach 25 years ago, they are now a clear reality. On a global scale, we can pride ourselves on high-quality and accessible public health care, maternity care, early childhood education, the pre-school sys- tem, a healthy environment etc. Of course, there is also a negative side. The economic and financial crisis, poor management of banks and com- panies, and finally also of the state. Nevertheless, we are celebrating the anniversary with pride. 80 Government Communication Office LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS EFFICIENT COHESION POLICY SYSTEM After the declaration of independence, it was necessary to first lay healthy foundations and secure in- An efficient system for implementing cohesion policy enables the drawing of European funds earmarked ternational recognition for the newly established country, which has been a full member of the EU and for development. The progress achieved with these funds can be seen in every Slovenian municipality. NATO since 2004. In the field of economic and educational infrastructure, 71 projects were implemented between 2007 and 2013, which contributed to the creation of jobs in business zones across Slovenia. Slovenia became financially independent in October 1991 through The majority of environmental projects involved the construction and renovation of water supply and one of the fastest and most successful currency conversions, with a municipal networks. Over 400 projects were co-financed, and more than 122,000 citizens obtained con- nections to sewage systems in agglomerations with less than 2,000 p.e., and over 170,000 people were 1:1 exchange rate that took a mere three days to establish, and Slo- provided with access to better quality and safer water supply systems with these funds. -

Akasvayu Girona

AKASVAYU GIRONA OFFICIAL CLUB NAME: CVETKOVIC BRANKO 1.98 GUARD C.B. Girona SAD Born: March 5, 1984, in Gracanica, Bosnia-Herzegovina FOUNDATION YEAR: 1962 Career Notes: grew up with Spartak Subotica (Serbia) juniors…made his debut with Spartak Subotica during the 2001-02 season…played there till the 2003-04 championship…signed for the 2004-05 season by KK Borac Cacak…signed for the 2005-06 season by FMP Zeleznik… played there also the 2006-07 championship...moved to Spain for the 2007-08 season, signed by Girona CB. Miscellaneous: won the 2006 Adriatic League with FMP Zeleznik...won the 2007 TROPHY CASE: TICKET INFORMATION: Serbian National Cup with FMP Zeleznik...member of the Serbian National Team...played at • FIBA EuroCup: 2007 RESPONSIBLE: Cristina Buxeda the 2007 European Championship. PHONE NUMBER: +34972210100 PRESIDENT: Josep Amat FAX NUMBER: +34972223033 YEAR TEAM G 2PM/A PCT. 3PM/A PCT. FTM/A PCT. REB ST ASS BS PTS AVG VICE-PRESIDENTS: Jordi Juanhuix, Robert Mora 2001/02 Spartak S 2 1/1 100,0 1/7 14,3 1/4 25,0 2 0 1 0 6 3,0 GENERAL MANAGER: Antonio Maceiras MAIN SPONSOR: Akasvayu 2002/03 Spartak S 9 5/8 62,5 2/10 20,0 3/9 33,3 8 0 4 1 19 2,1 MANAGING DIRECTOR: Antonio Maceiras THIRD SPONSOR: Patronat Costa Brava 2003/04 Spartak S 22 6/15 40,0 1/2 50,0 2/2 100 4 2 3 0 17 0,8 TEAM MANAGER: Martí Artiga TECHNICAL SPONSOR: Austral 2004/05 Borac 26 85/143 59,4 41/110 37,3 101/118 85,6 51 57 23 1 394 15,2 FINANCIAL DIRECTOR: Victor Claveria 2005/06 Zeleznik 15 29/56 51,8 13/37 35,1 61/79 77,2 38 32 7 3 158 10,5 MEDIA: 2006/07 Zeleznik -

European Perspectives

APRIL 2019, VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1 (17) 1 (17) UMBER N 10, OLUME 2019,V PRIL A articles EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES Digital diplomacy: aspects, approaches and practical use Viona Rashica Brain drain – current conditions and perspectives Ljupcho Kevereski and Bisera Kostadinovska- Stojchevska Eighty years since the midnight diplomatic pact: an overture to the Second World War Polona Dovečar Diplomacy and family life: co-existence or burden? Dragica Pungaršek Individualism as a determinant of successful ISSN 1855-7694 diplomats through the engagement of stereotyped sportspersons Milan Jazbec IFIMES – Special Consultative Status with 15 eur ECOSOC/UN since 2018 EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL ON EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES International Scientific Journal on European Perspectives EDITOR: Milan Jazbec ASSISTANT EDITOR: Nataša Šuštar B. EDITORIAL BOARD Matej Accetto (Católica Global School of Law, Portugal) • Dennis Blease (University of Cranfield, UK• Vlatko Cvrtila (University of Zagreb, Croatia) • Vladimir Prebilič (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Albert Rakipi (Albanian Institute for International Studies, Albania) • Erwin Schmidl (University of Vienna, Austria) • Vasilka Sancin (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Uroš Svete (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Katja Zajc Kejžar (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Jernej Zupančič (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Mitja Žagar (Institute for Ethnic Studies, Slovenia) • Jelica Štefanović Štambuk (University of Belgrade, Serbia) EDITORIAL ADVISORY -

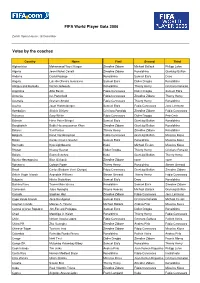

Votes by the Coaches FIFA World Player Gala 2006

FIFA World Player Gala 2006 Zurich Opera House, 18 December Votes by the coaches Country Name First Second Third Afghanistan Mohammad Yousf Kargar Zinedine Zidane Michael Ballack Philipp Lahm Algeria Jean-Michel Cavalli Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Gianluigi Buffon Andorra David Rodrigo Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Deco Angola Luis de Oliveira Gonçalves Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Ronaldinho Antigua and Barbuda Derrick Edwards Ronaldinho Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Argentina Alfio Basile Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Samuel Eto'o Armenia Ian Porterfield Fabio Cannavaro Zinedine Zidane Thierry Henry Australia Graham Arnold Fabio Cannavaro Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Austria Josef Hickersberger Samuel Eto'o Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Azerbaijan Shahin Diniyev Cristiano Ronaldo Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Bahamas Gary White Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Petr Cech Bahrain Hans-Peter Briegel Samuel Eto'o Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Bangladesh Bablu Hasanuzzaman Khan Zinedine Zidane Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Belarus Yuri Puntus Thierry Henry Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Belgium René Vandereycken Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Miroslav Klose Belize Carlos Charlie Slusher Samuel Eto'o Ronaldinho Miroslav Klose Bermuda Kyle Lightbourne Kaká Michael Essien Miroslav Klose Bhutan Kharey Basnet Didier Drogba Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Bolivia Erwin Sanchez Kaká Gianluigi Buffon Thierry Henry Bosnia-Herzegovina Blaz Sliskovic Zinedine Zidane none none Botswana Colwyn Rowe Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Steven Gerrard Brazil Carlos Bledorin Verri (Dunga) Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Zinedine Zidane British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Steven Gerrard Thierry Henry Fabio Cannavaro Bulgaria Hristo Stoitchkov Samuel Eto'o Deco Ronaldinho Burkina Faso Traore Malo Idrissa Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Zinedine Zidane Cameroon Jules Nyongha Wayne Rooney Michael Ballack Gianluigi Buffon Canada Stephen Hart Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Cape Verde Islands José Rui Aguiaz Samuel Eto'o Cristiano Ronaldo Michael Essien Cayman Islands Marcos A. -

National Programme of Sport 2014-2023

NATIONAL PROGRAMME OF SPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA 2014-2023 April 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 MISSION .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 STATE OF AFFAIRS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 4 VISION ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 5 OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 6 ACTIONS ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 6.1 Sports programmes ..................................................................................................................................... 12 6.1.1 Sport in the education system ........................................................................................................................ -

Prenesite Brošuro 2018

PRIŽGIMO NAVIJAŠKI ŽAR NA LJUBNEM Let's ignite the flame of support in Ljubno www.fis-ski.com fis svetovni pokal v smučarskih skokih za ženske - sponzorira viessmann 27.~28. januar 2018 pokrovitelj tekmovanja www.ljubno-skoki.si #ljubno2018 fis predstavitveni pokrovitelj Spored · Programme petek, 26. januar 2018 Prodaja vstopnic “Ljubno je Planica ženskih “Ljubno is the Planica of women's ski friday, 26th january 2018 Ticket sale skokov. Po obisku in vzdušju ga jumping. In terms of the number of 12.00 Uradni trening (2 seriji) www.eventim.si in prodajna nobena tekma deklet v svetovnem visitors and the atmosphere, no other Official Training (2 rounds) mesta v sistemu Eventim Si. pokalu ne prekaša,” event on the women's FIS World Cup Kvalifikacije Qualification Round www.eventim.si and sale points 14.00 calendar comes close to Ljubno,” in the Eventim Si system. je legendarni Primož Peterka izjavil v nekem sobota, 27. januar 2018 intervjuju in bolj se družba BTC z njim ne bi mogla said the legendary Primož Peterka. The BTC saturday, 27th january 2018 strinjati, saj je že sedmo leto zapored generalni Company could not agree more with our legendary Brezplačen parkirni prostor bo pokrovitelj tekem za Svetovni pokal na Ljubnem. ski jumper, since the company has been the 12.45 Poskusna serija Trial Round zagotovljen. Prizorišče je vsako leto bolj pripravljeno na izzive general sponsor of the World Cup competitions in 13.35 Slavnostna otvoritev Opening Ceremony Free-of-charge parking spaces. svetovnega pokala in postavlja Ljubno ob bok Ljubno for the seventh consecutive year. The venue 14.00 1. -

Vancouver Olympic Games 2010

In This Issue Vancouver Olympic Games 2010 - Vancouver Olympic Games 2010 This Friday, February Slovenia will be 12, will be marked by the represented at the Olympics by - Slovenian House at opening of the XXI Winter 47 athletes, which is the largest Olympic Games Olympic Games, held in delegation of athletes to the Vancouver, Canada, from winter Olympics in Slovene - Isakovič, Kajzer Win February 12 until February history. Seventeen women and Bloudek Prizes 28. thirty men will compete in - The Goverment of ten different Olympic events, Slovenia Adopts Exit ranging from alpine skiing, Strateg y cross-country skiing, ski- jumping, snowboarding, and - Inter view Series: figure skating to skeleton and Carole Ryavec freestyle skiing. - 60th Berlinale Petra Majdič in cross- country skiing and Tina Announcements Maze in alpine skiing are two sportswomen in whom -------------------------- Slovene fans put most of their - List to do/ see: hopes. - Gray Bukovnik’s Exhibition - Musical “Hair” More than 2,500 - Revolutionary Voices contestants from over 80 countries will compete for 86 sets of medals. The town of Whistler in British Columbia, Canada, will be the venue where most events will be On the photo: Tina Maze. held, whereas the opening ceremony will take place Petra Majdič, who has at the BC Place Stadium in so far had one of the most Vancouver, indoors for the successful seasons, is aspiring first time in the history of for at least one gold medal Olympic Games. in women’s cross-country Embassy’s Newsletter Page 1 February 12, 2010 sprint, where she is one of the main favorites. -

Acta Histriae

ACTA HISTRIAE ACTA ACTA HISTRIAE 23, 2015, 3 23, 2015, 3 ISSN 1318-0185 Cena: 11,00 EUR UDK/UDC 94(05) ACTA HISTRIAE 23, 2015, 3, pp. 309-590 ISSN 1318-0185 ACTA HISTRIAE • 23 • 2015 • 3 ISSN 1318-0185 UDK/UDC 94(05) Letnik 23, leto 2015, številka 3 Odgovorni urednik/ Direttore responsabile/ Darko Darovec Editor in Chief: Uredniški odbor/ Gorazd Bajc, Furio Bianco (IT), Flavij Bonin, Dragica Čeč, Lovorka Comitato di redazione/ Čoralić (HR), Darko Darovec, Marco Fincardi (IT), Darko Friš, Aleksej Board of Editors: Kalc, Borut Klabjan, John Martin (USA), Robert Matijašić (HR), Darja Mihelič, Edward Muir (USA), Egon Pelikan, Luciano Pezzolo (IT), Jože Pirjevec, Claudio Povolo (IT), Vida Rožac Darovec, Andrej Studen, Marta Verginella, Salvator Žitko Urednik/Redattore/ Editor: Gorazd Bajc Prevodi/Traduzioni/ Translations: Petra Berlot (angl., it., slo) Lektorji/Supervisione/ Language Editor: Petra Berlot (angl., it., slo) Stavek/Composizione/ Typesetting: Grafis trade d.o.o. Izdajatelj/Editore/ Published by: Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko / Società storica del Litorale© Sedež/Sede/Address: Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko, SI-6000 Koper-Capodistria, Kreljeva 3 / Via Krelj 3, tel.: +386 5 6273-296; fax: +386 5 6273-296; e-mail: [email protected]; www.zdjp.si Tisk/Stampa/Print: Grafis trade d.o.o. Naklada/Tiratura/Copies: 300 izvodov/copie/copies Finančna podpora/ Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike Slovenije / Slovenian Supporto finanziario/ Research Agency Financially supported by: Slika na naslovnici/ Foto di copertina/ Picture on the cover: Bodeča žica na slovensko-hrvaški meji december 2015 (Foto Zaklop) Barbed wire on the Slovenian-Croatian border, December 2015 (foto Zaklop) / Filo spinato al confine tra Slovenia e Croazia, dicembre 2015 (foto Zaklop) Redakcija te številke je bila zaključena 15. -

Jellyfish Modulate Bacterial Dynamic and Community Structure

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Jellyfish Modulate Bacterial Dynamic and Community Structure Tinkara Tinta, Tjasˇa Kogovsˇek, Alenka Malej, Valentina Turk* National Institute of Biology, Marine Biology Station, Piran, Slovenia Abstract Jellyfish blooms have increased in coastal areas around the world and the outbreaks have become longer and more frequent over the past few decades. The Mediterranean Sea is among the heavily affected regions and the common bloom - forming taxa are scyphozoans Aurelia aurita s.l., Pelagia noctiluca, and Rhizostoma pulmo. Jellyfish have few natural predators, therefore their carcasses at the termination of a bloom represent an organic-rich substrate that supports rapid bacterial growth, and may have a large impact on the surrounding environment. The focus of this study was to explore whether jellyfish substrate have an impact on bacterial community phylotype selection. We conducted in situ jellyfish - enrichment experiment with three different jellyfish species. Bacterial dynamic together with nutrients were monitored to assess decaying jellyfish-bacteria dynamics. Our results show that jellyfish biomass is characterized by protein rich organic matter, which is highly bioavailable to ‘jellyfish - associated’ and ‘free - living’ bacteria, and triggers rapid shifts in bacterial population dynamics and composition. Based on 16S rRNA clone libraries and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis, we observed a rapid shift in community composition from unculturable Alphaproteobacteria to culturable species of Gammaproteobacteria and Flavobacteria. The results of sequence analyses of bacterial isolates and of total bacterial community determined by culture independent genetic analysis showed the dominance of the Pseudoalter- omonadaceae and the Vibrionaceae families. -

Oton Župančič in Začetki Južnoslovanske Tvorbe Jožica Čeh

S tudia Historica S lovenica Studia Historica Slovenica Časopis za humanistične in družboslovne študije Humanities and Social Studies Review letnik 20 (2020), št. 1 ZRI DR. FRANCA KOVAČIČA V MARIBORU MARIBOR 2020 Studia Historica Slovenica Tiskana izdaja ISSN 1580-8122 Elektronska izdaja ISSN 2591-2194 Časopis za humanistične in družboslovne študije / Humanities and Social Studies Review Izdajatelja / Published by ZGODOVINSKO DRUŠTVO DR. FRANCA KOVAČIČA V MARIBORU/ HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF DR. FRANC KOVAČIČ IN MARIBOR http://www.zgodovinsko-drustvo-kovacic.si ZRI DR. FRANCA KOVAČIČA V MARIBORU/ ZRI DR. FRANC KOVAČIČ IN MARIBOR Uredniški odbor / Editorial Board dr. Karin Bakračevič, † dr. Ivo Banac (ZDA / USA), dr. Rajko Bratuž, dr. Neven Budak (Hrvaška / Croatia), dr. Jožica Čeh Steger, dr. Darko Darovec, dr. Darko Friš, dr. Stane Granda, dr. Andrej Hozjan, dr. Gregor Jenuš, dr. Tomaž Kladnik, dr. Mateja Matjašič Friš, dr. Aleš Maver, dr. Jože Mlinarič, dr. Jurij Perovšek, dr. Jože Pirjevec (Italija / Italy), dr. Marijan Premović (Črna Gora / Montenegro), dr. Andrej Rahten, dr. Tone Ravnikar, dr. Imre Szilágyi (Madžarska / Hungary), dr. Peter Štih, dr. Polonca Vidmar, dr. Marija Wakounig (Avstrija / Austria) Odgovorni urednik / Responsible Editor dr. Darko Friš Zgodovinsko društvo dr. Franca Kovačiča Koroška cesta 53c, SI–2000 Maribor, Slovenija e-pošta / e-mail: [email protected] Glavni urednik / Chief Editor dr. Mateja Matjašič Friš Tehnični urednik / Tehnical Editor David Hazemali Članki so recenzirani. Za znanstveno vsebino prispevkov so odgovorni avtorji. Ponatis člankov je mogoč samo z dovoljenjem uredništva in navedbo vira. The articles have been reviewed. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their articles. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the publisher's prior consent and a full mention of the source. -

Between the House of Habsburg and Tito a Look at the Slovenian Past 1861–1980

BETWEEN THE HOUSE OF HABSBURG AND TITO A LOOK AT THE SLOVENIAN PAST 1861–1980 BETWEEN THE HOUSE OF HABSBURG AND TITO A LOOK AT THE SLOVENIAN PAST 1861–1980 EDITORS JURIJ PEROVŠEK AND BOJAN GODEŠA Ljubljana 2016 Between the House of Habsburg and Tito ZALOŽBA INZ Managing editor Aleš Gabrič ZBIRKA VPOGLEDI 14 ISSN 2350-5656 Jurij Perovšek in Bojan Godeša (eds.) BETWEEN THE HOUSE OF HABSBURG AND TITO A LOOK AT THE SLOVENIAN PAST 1861–1980 Technical editor Mojca Šorn Reviewers Božo Repe Žarko Lazarevič English translation: Translat d.o.o. and Studio S.U.R. Design Barbara Bogataj Kokalj Published by Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino/Instute of Contemporaray History Printed by Medium d.o.o. Print run 300 copies The publication of this book was supported by Slovenian Research Agency CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 94(497.4)"1861/1980"(082) BETWEEN the House of Habsburg and Tito : a look at the Slovenian past 1861-1980 / editors Jurij Perovšek and Bojan Godeša ; [English translation Translat and Studio S. U. R.]. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino = Institute of Contemporary History, 2016. - (Zbirka Vpogledi, ISSN 2350-5656 ; 14) ISBN 978-961-6386-72-2 1. Perovšek, Jurij 287630080 ©2016, Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, hired out, transmitted, published, adapted or used in any other way, including photocopying, printing, recording or storing and publishing in the electronic form without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.