Table of Contents 1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERIA I, PLAY-OFF, ETAPA a X-A - 07 Iunie 2014

SERIA I, PLAY-OFF, ETAPA A X-A - 07 iunie 2014 - SC BACĂU 1 FC CLINCENI 1 Marcatori: Căinari ’48 / Viţelaru ’74 M. Oltean - Luncanu, Adăscăliţei, Burcă, Sascău - L. Dumitriu, Ţuţu - Căinari (M. Şchiopu ’90+2), Cl. Tudor (Taban ’77), Hurdubei (cpt.) - Predoiu (Bg. Rusu ’60) Antrenor: Viorel Tănase Eliminat: Sascău ’75 (două galbene) C. Lungu - St. Stancu, A. Niţu (cpt.) (Marciuc ’27), Viţelaru, Bg. Straton - I. Roşu (Cr. Puşcaş ’46), Olariu, Bg. Pătraşcu, C. Dedu - Vl. Rusu (Venţer ’68), H. Koné Antrenor: Florentin Rădulescu Stadion: Aerostar (Bacău); Spectatori: 100; Corespondent: Horia Alexoae; Arbitru: Cristina Mariana Trandafir 3 (Bucureşti); Asistenţi: Dan Lucian Ilieş 3 (Braşov) şi Bogdan Ioan Dragoş 3 (Făgăraş); Jucătorul meciului: Cornel Căinari 3 UNIREA SLOBOZIA 1 RAPID BUCUREŞTI 1 Marcatori: M. Florea ’43 / Ciolacu ’15 L. Dobre - St. Stan, Fl. Tudorache, R. Soare (cpt.), C. Toma - Macare, Ivaşcă (Coconaşu ’46) - Ibrian (Oct. Ursu ’70), Bolat, M. Florea - E. Nanu (Drăguţ ’51) Antrenor: Adrian Mihalcea Drăghia - Al. Coman, D. Lung, Al. Iacob, I. Voicu (cpt.) - Ct. Păun, Selagea (M. Stoica ’46, Tânc ’86) - M. Martin, V. Negru, E. Dică (Cl. Herea ’66) - Ciolacu Antrenor: Viorel Moldovan Eliminat: D. Lung ’67 (două galbene) Stadion: “1 Mai” (Slobozia); Spectatori: 3.000; Corespondent: Ionuţ Văgăonescu; Arbitru: Mihai Amorăriţei 2 (Câmpina); Asistenţi: Marius Florin Badea 2 (Râmnicu Vâlcea) şi Romică Bîrdeş 2 (Piteşti); Jucătorul meciului: Marian Florea 3 CSMS IAȘI 3 ACS BERCENI 1 Marcatori: Ov. Mihalache ’13, L. Mihai ’56, ’58 / V. Ștefan ’7 A. Bălan - Radovic (Bosoi ’50), Ov. Mihalache, Fl. Plămadă, I. Vladu - Olah (Mug. Dedu ’79), Al. Crețu - Onofraș (cpt.), L. -

European Perspectives

APRIL 2019, VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1 (17) 1 (17) UMBER N 10, OLUME 2019,V PRIL A articles EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES Digital diplomacy: aspects, approaches and practical use Viona Rashica Brain drain – current conditions and perspectives Ljupcho Kevereski and Bisera Kostadinovska- Stojchevska Eighty years since the midnight diplomatic pact: an overture to the Second World War Polona Dovečar Diplomacy and family life: co-existence or burden? Dragica Pungaršek Individualism as a determinant of successful ISSN 1855-7694 diplomats through the engagement of stereotyped sportspersons Milan Jazbec IFIMES – Special Consultative Status with 15 eur ECOSOC/UN since 2018 EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL ON EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES International Scientific Journal on European Perspectives EDITOR: Milan Jazbec ASSISTANT EDITOR: Nataša Šuštar B. EDITORIAL BOARD Matej Accetto (Católica Global School of Law, Portugal) • Dennis Blease (University of Cranfield, UK• Vlatko Cvrtila (University of Zagreb, Croatia) • Vladimir Prebilič (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Albert Rakipi (Albanian Institute for International Studies, Albania) • Erwin Schmidl (University of Vienna, Austria) • Vasilka Sancin (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Uroš Svete (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Katja Zajc Kejžar (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Jernej Zupančič (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) • Mitja Žagar (Institute for Ethnic Studies, Slovenia) • Jelica Štefanović Štambuk (University of Belgrade, Serbia) EDITORIAL ADVISORY -

Marius Lăcătuș

959.168 DE VIZITATORI unici lunar pe www.prosport.ro (SATI) • 619.000 CITITORI zilnic (SNA octombrie 2007 - octombrie 2008) Numărul 3600 Marți, 21 aprilie 2009 24 pagini Tiraj: 110.000 AZI AI BANI, MAȘINI ȘI CUPOANE DE PARIURI ÎN ZIAR »17 ATENȚIE!!! VALIZA CU BANI Cotidian național de sport editat de Publimedia Internațional - Companie MediaPro EDIȚIE NAȚIONALĂ de AZI AI TALON! GHEORGHIU Unii conducători de club GHEORGHIU află prin intermediul LIGA LUI MITICĂ, INTERMEDIAR LPF cine îi arbitrează BOZOVIC, TURIST cu mult înaintea ÎNTRE CLUBURI ŞI ARBITRI! anunului oficial »14 LA RAPID Muntenegreanul evacuat din casă speră să devină liber România pentru că nu avea viză de DIALOG DE TAINĂ ÎNTRE PATRON, ANTRENOR muncă, ci de turist »8-9 ŞI JUCĂTORI ÎN VESTIARUL STELEI de NEGOESCU ZOOM: Gheorghiu explică de MARIAN »2-5 de ce l-a bătut Rapid pe Foto: Alexandru HOJDA Lucescu jr »18 VORBELE ETAPEI: Caramavrov şi Geantă despre eliberarea Stelei »19 SPECIAL Mircea Rednic pare că se ghidea- ză la Dinamo după deviza „antrena- mentele lungi şi dese, cheia marilor succese“ GIGI BECALI: »6-7 DOAR Cel mai bun ziar de sport din din sport de ziar bun mai Cel O ZI LIBERĂ ro „Vreau titlul!“ ÎN DOUĂ MARIUS LĂCĂTUȘ: SĂPTĂMÂNI! de PITARU N-AM FOST LA EURO PENTRU CĂ AVEAM „i-l iau!“ MÂNECI SCURTE! Lubos Michel a mai găsit o • Becali îl împinge pe Dayro înapoi între titulari! • Ghionea a aflat ieri scuză pentru greşeala care că mâine e suspendat! • Steaua – CFR, în premieră fără prime • Clujenii ne-a lăsat acasă la Euro www.prosport. -

Universite Catholique De Louvain

UNIVERSITÉ CATHOLIQUE DE LOUVAIN INSTITUT DES SCIENCES DU TRAVAIL STUDY ON THE REPRESENTATIVENESS OF THE SOCIAL PARTNER ORGANISATIONS IN THE PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL PLAYERS SECTOR PROJECT NO VC/2004/0547 February 2006 Research project conducted on behalf of the Employment and Social Affairs DG of the European Commission STAFF WORKING ON THIS STUDY Author of the report Alexandre CHAIDRON, researcher Cécile Arnould, researcher Coordinators Prof. Armand SPINEUX and Prof. Evelyne LEONARD Research Team Prof. Bernard FUSULIER Prof. Pierre REMAN Delphine ROCHET, researcher Isabelle VANDENBUSSCHE, researcher Administrative co-ordination Myriam CHEVIGNE Network of National Experts Austria: Franz Traxler, Institut für Soziologie – Universität Wien. Belgium: Jean Vandewattyne, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) Cyprus: Savvas Katsikides, Maria Modestou and Evros I. Demetriades, Department of Social and Political Science - University of Cyprus Czech Republic: Ales Kroupa and Jaroslav Helena, Research Institute for Labour and Social Affairs - Charles University of Prague Denmark: Carsten.Jorgensen, Forskningscenter for Arbejdsmarkeds- og Organisationsstudier, FAOS – Department of Sociology, University of Copenhagen Estonia: Kaia Philips and Raul Eamets, University of Tartu 2 Finland: Pekka Ylostalo, University of Helsinki, Department of Sociology France: Solveig Grimault, Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris Germany: Dieter Sadowski, Catharina Leilich, Dana Liebmann, Oliver Ludewig, Mihai Paunescu, Martin Schneider and Susanne Warning, Institut für Arbeitsrecht und Arbeitsbeziehungen in der Europäischen Gemeinschaft, IAAEG - Universität Trier Greece: Aliki Mouriki, National Center for Social Research – Athens Hungary: Csaba Makó, Institute of Sociology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Ireland: Pauline Conroy and Niamh Murphy, Ralaheen Ltd Italy: Franca Alacevich and Andrea Bellini, Università degli studi di Firenze – Dipartemento di scienza della politica e sociologia politica. -

QSL CEO Reveals Plans to Complete Season

NBA | Page 3 MOTORSPORT | Page 5 Lakers’ LeBron UK quarantine eager to get would make back to British GP basketball impossible: F1 Wednesday, May 20, 2020 FOOTBALL Ramadan 27, 1441 AH QSL CEO reveals GULF TIMES plan to complete season SPORT Page 2 FOOTBALL Six positive tests for Covid-19 at Premier League clubs ‘PLAYERS OR CLUB STAFF WHO HAVE TESTED POSITIVE WILL NOW SELF-ISOLATE FOR A PERIOD OF SEVEN DAYS’ Agencies spread testing conducted by other London major leagues hoping to complete the season. Liverpool captain Jordan Hender- ix positive cases for coronavirus son was among those returning for the have been detected at three Pre- league leaders while Tottenham also mier League clubs after players saw some of their players come back. Sand staff were tested ahead of a Manchester United said their players return to training, England’s top flight would not return until Wednesday. said yesterday. Germany’s top two divisions regis- “The Premier League can today con- tered 10 positive cases out of 1,724 tests firm that, on Sunday 17 May and Mon- two weeks ago ahead of their return to day 18 May, 748 players and club staff action last weekend. were tested for Covid-19,” the league Five players from Spain’s top two di- said in a statement. visions tested positive last week before “Of these, six have tested positive La Liga’s return to group training. from three clubs.” Premier League clubs are aiming for No details were released over which a return to action by the middle of next individuals or clubs are affected. -

About Bulgaria

Source: Zone Bulgaria (http://en.zonebulgaria.com/) About Bulgaria General Information about Bulgaria Bulgaria is a country in Southeastern Europe and is situated on the Balkan Peninsula. To the north the country borders Rumania, to the east – the Black Sea, to the south – Turkey and Greece, and to the west – Yugoslavia and Macedonia. Bulgaria is a parliamentary republic with a National Assembly (One House Parliament) of 240 national representatives. The President is Head of State. Geography of Bulgaria The Republic of Bulgaria covers a territory of 110 993 square kilometres. The average altitude of the country is 470 metres above sea level. The Stara Planina Mountain occupies central position and serves as a natural dividing line from the west to the east. It is a 750 km long mountain range stretching from the Vrushka Chuka Pass to Cape Emine and is part of the Alpine-Himalayan mountain range. It reaches the Black Sea to the east and turns to the north along the Bulgarian-Yugoslavian border. A natural boundary with Romania is the Danube River, which is navigable all along for cargo and passenger vessels. The Black Sea is the natural eastern border of Bulgaria and its coastline is 378 km long. There are clearly cut bays, the biggest two being those of Varna and Bourgas. About 25% of the coastline are covered with sand and hosts our seaside resorts. The southern part of Bulgaria is mainly mountainous. The highest mountain is Rila with Mt. Moussala being the highest peak on the Balkan Peninsula (2925 m). The second highest and the mountain of most alpine character in Bulgaria is Pirin with its highest Mt. -

Liga 2, Etapa 19, Seria I

LIGA 2, ETAPA 19, SERIA I BUCOVINA POJORÂTA 1 ‐ 1CS BALOTEȘTI 0 ‐ 1 27.02.2016, ora 11:00, stadion Comunal (Pojorâta) Arbitru: Laurenţiu Ionaşcu Asistenţi: Ovidiu Aruşoaiei Rezervă: Adrian Frăţilă Adrian Vornicu NRNUME ŞI PRENUME GOL NRNUME ŞI PRENUME GOL 1 30Raul Pop 33 Corneliu Fulga 2 26Daniel Cristescu Constantin Dedu 3 17Andrei Răuţă 14 Valentin Flămânzeanu 4 427Andu Moisii Bogdan Marciuc 5 521Traian Jarda Costin Mirescu 6 11Valentin Buhăcianu 17 Ionuţ Sandu 7 88Ionuţ Jugaru Marius Antoche 8 21Cornel Căinari 20 Alin Gojnea 9 15Claudiu Juncănaru 7 Paul Florin Radu 10 20Alexandru Marin 10 Claudiu Herea 11 990938Marius Coman Marius Bâtfoi 12 11Ionuţ Puianu Teodor Rudniţchi 13 10Vlad Stănescu 19 Gabriel Lupaşcu 14 14Alexandru Nuţescu 18 Petre Ioniţă 15 62Vasile Vitu Antonio Stelitano 16 725Răzvan Acostăchioaie Valentin Niculae 17 16Ionuţ Duţică 4 Dorinel Popa 18 25Robert Pîslaru 26 Andrei Pătraşcu 19 Antrenor: Bogdan Grosu Antrenor: Marius Oprea SCHIMBĂRIMINUT SCHIMBĂRI MINUT 11 ↔ 10 Vl. Stănescu 46 20 ↔ 25 Fl. Niculae 86 4 ↔ 16 Duţică 67 7 ↔ 18 P. Ioniţă 89 8 ↔ 25 Pîslaru 82 10 ↔ 19 G. Lupaşcu 90+2 AVERTISMENTEMINUT AVERTISMENTE MINUT Andrei Răuţă 19Marius Bâtfoi 89 Cornel Căinari 26Paul Florin Radu 90 Marius Coman 53 LIGA 2, ETAPA 19, SERIA I DACIA UNIREA BRĂILA 4 ‐ 0 FARUL CONSTANȚA 3 ‐ 0 27.02.2016, ora 11:00, stadion Municipal (Brăila) Arbitru: Andrei Chivulete Asistenţi: Ionel Dumitru Rezervă: Valentin Porumbel Florian Vişan NRNUME ŞI PRENUME GOL NRNUME ŞI PRENUME GOL 1 87Cristian Mitrea 1 Răzvan Began 2 225Gabriel Niţă Ciprian -

FE-14 Pfingstturnier Vom 22.05.2021

FE-14 Pfingstturnier vom 22.05.2021 Presenter: SC Kriens Date: 22.05.2021 Event Location: Stadion Kleinfeld, Horwerstrasse 24a, 6010 Kriens Start: 09:00 Match Duration in Group Phase: 25 minutes Match Duration in Final Phase: 25 minutes Placement Mode: Points - Goal Difference - Amount of Goals - Head-to-Head Record Participants Group A Group B Live Results 1 SC Kriens 6 FC Aarau 2 BSC Young Boys 7 FC Zürich 3 Team TOBE 8 Concordia Basel 4 AC Bellinzona 9 FC Lugano 5 FC Winterthur 10 FC Luzern Preliminary Round No. C Start Gr Match Result Group A 1 1 09:00 A SC Kriens FC Winterthur 0 : 0 Pl Participant G GD Pts 2 2 09:00 A BSC Young Boys Team TOBE 1 : 1 1. BSC Young Boys 6 : 1 5 8 3 1 09:30 B FC Aarau FC Luzern 0 : 1 2. FC Winterthur 5 : 1 4 8 4 2 09:30 B FC Zürich Concordia Basel 1 : 0 3. Team TOBE 2 : 4 -2 5 5 1 10:00 A AC Bellinzona SC Kriens 0 : 0 4. SC Kriens 0 : 3 -3 2 6 2 10:00 A Team TOBE FC Winterthur 0 : 3 5. AC Bellinzona 1 : 5 -4 2 7 1 10:30 B FC Lugano FC Aarau 0 : 2 8 2 10:30 B Concordia Basel FC Luzern 1 : 1 Group B 9 1 11:00 A AC Bellinzona BSC Young Boys 0 : 3 Pl Participant G GD Pts 10 2 11:00 A Team TOBE SC Kriens 1 : 0 1. -

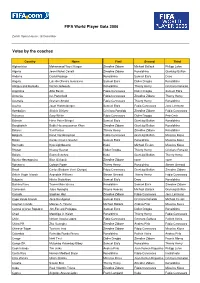

Votes by the Coaches FIFA World Player Gala 2006

FIFA World Player Gala 2006 Zurich Opera House, 18 December Votes by the coaches Country Name First Second Third Afghanistan Mohammad Yousf Kargar Zinedine Zidane Michael Ballack Philipp Lahm Algeria Jean-Michel Cavalli Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Gianluigi Buffon Andorra David Rodrigo Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Deco Angola Luis de Oliveira Gonçalves Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Ronaldinho Antigua and Barbuda Derrick Edwards Ronaldinho Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Argentina Alfio Basile Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Samuel Eto'o Armenia Ian Porterfield Fabio Cannavaro Zinedine Zidane Thierry Henry Australia Graham Arnold Fabio Cannavaro Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Austria Josef Hickersberger Samuel Eto'o Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Azerbaijan Shahin Diniyev Cristiano Ronaldo Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Bahamas Gary White Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Petr Cech Bahrain Hans-Peter Briegel Samuel Eto'o Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Bangladesh Bablu Hasanuzzaman Khan Zinedine Zidane Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Belarus Yuri Puntus Thierry Henry Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Belgium René Vandereycken Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Miroslav Klose Belize Carlos Charlie Slusher Samuel Eto'o Ronaldinho Miroslav Klose Bermuda Kyle Lightbourne Kaká Michael Essien Miroslav Klose Bhutan Kharey Basnet Didier Drogba Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Bolivia Erwin Sanchez Kaká Gianluigi Buffon Thierry Henry Bosnia-Herzegovina Blaz Sliskovic Zinedine Zidane none none Botswana Colwyn Rowe Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Steven Gerrard Brazil Carlos Bledorin Verri (Dunga) Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Zinedine Zidane British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Steven Gerrard Thierry Henry Fabio Cannavaro Bulgaria Hristo Stoitchkov Samuel Eto'o Deco Ronaldinho Burkina Faso Traore Malo Idrissa Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Zinedine Zidane Cameroon Jules Nyongha Wayne Rooney Michael Ballack Gianluigi Buffon Canada Stephen Hart Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Cape Verde Islands José Rui Aguiaz Samuel Eto'o Cristiano Ronaldo Michael Essien Cayman Islands Marcos A. -

European Qualifiers

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2019/20 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Stadiumi Fadil Vokrri - Pristina Monday 25 March 2019 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Kosovo Group A - Matchday 2 Bulgaria Last updated 13/11/2019 11:05CET EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS OFFICIAL SPONSORS Head coach 2 Legend 3 1 Kosovo - Bulgaria Monday 25 March 2019 - 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Match press kit Stadiumi Fadil Vokrri, Pristina Head coach Bernard Challandes Date of birth: 28 July 1951 Nationality: Swiss Playing career: Le Locle (twice), Urania Genève Sport, Saint-Imier Coaching career: Saint-Imier, Le Locle, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Yverdon-Sport, Young Boys (twice), Servette, Switzerland (youth), Switzerland Under-21, Zürich, Sion, Neuchâtel Xamax, Thun, Armenia, Kosovo • Bernard Challandes has quietly carved out an impressive coaching CV since his career started in earnest when he took over at Yverdon in 1987. He stayed in the post for seven seasons, winning four lower-league titles, before moving to Young Boys. • His stay in Berne proved nowhere near as lengthy or successful, however, Challandes departing in 1995 with the club finishing bottom of the first phase of the 12-team Swiss top flight after collecting just 17 points. A subsequent spell at Servette proved short-lived, and there followed a lengthy spell out of the limelight , during which he coached Switzerland’s Under-17 and Under-18 teams. • The Le Locle native took over the Switzerland Under-21 side in 2001. The highlight of his six years in charge came in 2002, when a team including Alexander Frei, Ludovic Magnin and Daniel Gygax reached the UEFA European Under-21 Championship semi-finals on home soil. -

Impact of Mergers and Acquisitions on Sport Performance of Football Clubs in the Highest Professional League in Poland

Service Management 1/2015, Vol. 15, ISSN: 1898-0511 | website: www.wzieu.pl/SM | DOI: 10.18276/smt.2015.15-09 | 77–86 IMPACT OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS ON SPORT PERFORMANCE OF FOOTBALL CLUBS IN THE HIGHEST PROFESSIONAL LEAGUE IN POLAND Szczepan Kościółek,1 K arolina Nessel2 1 Cracow University of Economics e-mail: [email protected] 2 Jagiellonian University in Kraków e-mail: [email protected] Received 25 March 2015 Accepted 1 June 2015 JEL classification G34, L83, Z21 Keywords Ekstraklasa, football, mergers and acquisitions, sports club, sport performance Abstract Mergers and acquisitions (M & As) in professional sports evoke strong emotions. Whereas for some econo- mists (and club owners) they are just business operations aimed to improve sport and financial performance of organizations, the supporters often reject this proposition on the grounds of identity and symbol issues. Given the lack of studies devoted to consolidation operations in Polish professional sports, the paper undertakes the analysis of M & As in the highest professional football league in Poland (Ekstraklasa) since 1989 with the aim to verify their impact on sport performance of the football clubs involved. The results of this multiple case study indicate that the main motivations for M & As in the sports club context are the same as in other industries (search for specific assets, strategic considerations, profit and loss calculations). In addition, the success rate also resembles the one in other sectors: only in one case (out of four studied) the merger has led to a clear and lasting improvement of sport performance (although not an immediate one). -

Kiesőhelyen Vásárhely Síbajnok Életpályája Ért Véget

2011. sZEPtember 28., sZERDA hargitanépe | 12. oldAL hírfolyam liek: 1. Erőss Béla (Csíkszereda), 2. Vrabie fejlődést látunk” – fogalmazott Lembergben > Vb – 2014. A FIFA különleges bizton- Gheorghe (Csíkszereda), Simon László a francia sportdiplomata. A városban, amely sági szakértőt jelölt ki az október 11-i Irán– > Tenisz. A hétvégén került megrende- (Csíkszereda) és Kósa Ferenc (Sepsiszent- a négy ukrajnai helyszín egyike, elsősorban a Bahrein világbajnoki selejtezőmérkőzésre, zésre Csíkszeredában a Szatmári-kupával györgy). A versenyt az Amigo, a Balu Kaland- repülőtér és az október végén nyíló stadion mert a két ország közötti politikai feszültség díjazott egyéni felnőtt teniszverseny. Ered- park, a Iang Impex, a Nextra, a Tusnad Rt. és a munkálatairól informálódott Platini, aki elé- miatt rendkívüli veszélytől tart. A két fordu- mények: 35 éven aluliak: 1. Csiszér Csaba Várdomb panzió támogatta. gedett volt a látottakkal. Az UEFA-delegáció ló után 4-4 ponttal a selejtezőcsoport első két (Székelyudvarhely), 2. Vrabie Adrian (Csík- Doneckben és Harkivban is megtekintette helyén álló gárda nagy csatát vívhat a gyepen, szereda), 3. Berekméri András (Csíkszereda) > EURO – 2012. 256 nappal a jövő évi az előkészületeket, majd tegnap, Kijevben de azon kívül lehetnek az igazi bonyodalmak. és Hodor Levente (Kézdivásárhely); 50 éven labdarúgó-Európa-bajnokság megnyitó- Platini találkozott Viktor Janukovics ukrán A FIFA attól tart, hogy a siíta Irán államveze- aluliak: 1. Berekméri András (Csíkszereda), ja előtt a társrendező Ukrajnába látogatott elnökkel. A fővárosban rendezik 2012. júli- tői a meccset kihasználva megpróbálja újabb 2. Németh Csaba (Sepsiszentgyörgy), 3. Michel Platini, a kontinentális futballszövetség us elsején az Eb döntőjét. A lengyel–ukrán lázadásra felbujtani a bahreini siíta kisebbsé- Szatmári Bendegúz (Csíkszereda) és Ciornei (UEFA) elnöke, aki szerint a házigazda nagy közös rendezésű kontinensviadal június 8-án get, amelynek felkelését az év első felében erő- Ovidiu (Csíkszereda); 50 éven felü- lépéseket tett az előkészületek terén.