'Skill Vs. Scale': the Transformation of Traditional Occupations in the Androon Shehr1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eid-Ul-Adha Plan

Eid ul Adha Plan 2017 Page 0 PREFACE This is LWMC’s Eid-ul-Azha plan 2017. This plan will cover detailed information regarding Solid Waste Management (SWM) services, which shall be provided by LWMC during Eid days. LWMC is going to make special arrangements for Solid Waste Management (SWM) on the eve of Eid-ul-Azha. LWMC in coordination with Turkish Contractors (M/s. Albayrak & M/s. Ozpak) will attempt to offer exemplary cleanliness arrangements on the eve of Eid-ul-Azha. The standard SWM activities will mainly focus on prompt collection, storage, transportation and disposal of animal waste during all three days of Eid. All the staff of LWMC will remain on board during Eid days to provide efficient SWM services to the citizens of Lahore. LWMC will establish Eid Camps in each Union Council of Lahore, not only to address the complaints of the citizens but to efficiently coordinate cleanliness activities in the respective UC’s as well. Moreover, awareness material and garbage bags for animal waste will also be available in these camps. A control room will be established in LWMC head office with special focus to coordinate collective operational activities during Eid days. In order to manage animal waste, LWMC is going to distribute 2 Million garbage bags in Lahore. The garbage bags will be made available free of cost in respective UC Camps / Zonal Office, Major Masajids / Eid Gahs. Similarly, for prompt collection of animal waste, LWMC will hire pickups 2 days before Eid for garbage bag distribution, awareness & waste collection. 1089 pickups will be hired on first day, 1025 on second and 543 on third day of Eid. -

Annual Report, 1928-29

II ANNUAL REPORT, 1928-29. Lahore: Printed. b, the Superintendent, Covtn~.mcut Printinr, Pa.njab. 1929. PUNJAB PRISONERS' AID SOCIETY. Office Bearers. Patron :-His ExcellP!WJ' Sir GEOFFREY FrTZIIEllVEY DEMoN'nronENCY, Kc.v.o., K.c.u., C.B.E., I.C.S., Governor of the Punjab. President :-Hon'ble ~Ir. A. U. Srow, O.B.E., I.C.S., Finance illember, Punjab. Vice-Presi.lcnls :-Lula lL~nKrsrrEN LAL, Sir ABDUL QADIR, Sir 2\IurrA~I:IrAD SrraFI, Raja NAnENDnA NATH, Sir SuNDER SINGH, Majithia, und Khan Bahadar ~IurrAM'JAD HAYAT Qureshi. Honorary Secretaries :-B. L. RALLIA RAM, Esq., anu Pandit HARADATTA SrrARMA. Members of the Executive Committee. Lieutenant-Colonel F. A. BARKER. Di2irict :MagiBtrate, Lahore. Major N. D. Puru, BLS. I{han Buhadur Sheikh A~un ALI. Lala LAJPAT Ru, SAnNI. Syed MorrsiN SnArr. The Reclamation Officer. Sir ABDUL QADIR. W. M. Hu~m, Esq. lilian Bahadur Sardar HABIB ULLAII. J. C. Souza, Esq. Captain DEVINDRA SINon, Otto. Miss CAnoAun, and the Office Bearers. ANNUAL REPORT. 1. General.-The standard of citizenship prevalent _in -a country is a very imp?rtan~ factor in i~s moral an.d mate~al advance. An ideal citizen IS not only mterested m ~eepmg himself " within the law " and performing s.uch fu!'J.CtiOns as . are incumbent upon him as a mer;nber ~f his nation .a~d a resident of his city but he regards It as his duty and pnVIlega to render help to 'others to follo:w his ex~mple. He ~s .not ·content with immunity from eVIl operations of a cnmmal ·Or a law-breaker, but he is on the other hand interested in the law-breaker and is anxious to tum him into a useful citizen. -

Shareholders Without CNIC.PDF

Gharibwal Cement Limited DETAIL OF WITHOUT CNIC SHAREHOLDERS S.No. Folio Name Address Current Net Dividend shareholding (Net of Zakat and Balance tax) 1 1 HAJI AMIR UMAR C/O.HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR COTTON MERCHANT,3RD FLOOR COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG, MCLEOD ROAD, P.O.BOX.NO.4124 586 KARACHI 578 2 3 MR.MAHBOOB AHMAD MOTI MANSION, MCLEOD ROAD, LAHORE. 11 11 3 11 MRS.FAUZIA MUGHIS 25-TIPU SULTAN ROAD MULTAN CANTT 1,287 1,271 4 19 MALIK MOHAMMAD TARIQ C/O.MALIK KHUDA BUX SECRETARY AGRICULTURE (WEST PAKISTAN), LAHORE. 110 108 5 20 MR. NABI AHMED CHAUDHRI, C/O, MODERN MOTORS LTD, VOLKSWAGEN HOUSE, P.O.BOX NO.8505, BEAUMONT ROAD, KARACHI.4. 2,193 2,166 6 24 BEGUM INAYAT NASIR AHMED 134 C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 67 66 7 26 MRS. AMTUR RAUF AHMED, 14/11 STREET 20, KHAYABAN-E-TAUHEED, PHASE V,DEFENCE, KARACHI. 474 468 8 27 MRS.AMTUL QAYYUM AHMED 134-C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 26 25 9 31 MR.ANEES AHMED C/O.DR.GHULAM RASUL CHEEMA BHAWANA BAZAR, FAISALABAD 649 642 10 36 MST.RAFIA KHANUM C/O.MIAN MAQSOOD A.SHEIKH M/S.MAQBOOL CO.LTD ILAMA IQBAL ROAD, LAHORE. 1,789 1,767 11 37 MST.ABIDA BEGUM C/O HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR 3RD FLOOR. COTTON EXCHANGE BUILDING, 1.1.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD, KARACHI. 2,572 2,540 12 39 MST.SAKINA BEGUM F-105 BLOCK-F ALLAMA RASHID TURABI ROAD NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2,657 2,625 13 42 MST.RAZIA BEGUM C/O M/S SADIQ SIDDIQUE CO., 32-COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG., I.I.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI. -

Final Voter List Election 2020-2021

Women Chamber of Commerce & Industry Lahore Division Final Voter List 2020-2021 Membership NTN Of Name of Authorised S.# Company Name Type of Business Business Address NIC No Company Representative 40-A-CMA Colony lane No 2, 1 00322 TULIP PVT LTD Trade 1765035-6 Ms. Lubna Bhayat 35200-1503144-4 Shami Road Lahore Office # 410, 4th Floor, Al- Modelo Developers Pvt 2 00382 Consultant Qasir heights, 1 babr Block, 7344768-3 Ms Shagufta Rehman 35201-4180131-4 Ltd garden Town Lahore 507, 5th Floor, Landmark Exporter/Manufactur 3 00375 MAAN Steel Plaza, Jail Road, Gulberg Town, 3049226-2 Ms. Hina Fouzia 35202-2692217-2 er Lahore 4 00300 CRESCENT SYNTEHTICS Manfacturer 221-M DHA Lahore 3086180-2 Ms.Tabassum Anwar 35201-5036833-0 5 00299 ACME INSTITUTE services 97-J Block Gulb erg 3 3128999-1 Ms.Qura- Tul Ain 35202-7250540-8 6 00077 Maurush Cane Furniture Manaufacturar 14-E-3-Gulberg-3 Lahore 3148030-6 Mrs.Nazi khalid 35202-2324349-4 Don Valley 7 00001 Pharmaceuticals (Pvt) Manufacturer 39-Main Peco Road Lahore. 1491930-3 Dr. Shehla Javed Akram 35202-9317913-0 Ltd Sofia Abad, 18 km, Feroze Pur 8 00002 General Machines Manufacturer 1892032-2 Ms Qaisra Sheikh 35202-7009646-2 Road Lahore. 9 00003 Kokab Kraft Manufacturer 49- Mzang Road Lahore 1315688-8 Mrs. Kokab Parveen 42201-0642589-9 Paradigm Tours (PVT) C-6 Seabreeze Sher Shah Block 10 00004 Services 2250623 Mrs. Iram Shaheen Malik 35200-1441309-4 LTD New Garden Town , Inter Globe Travel & 108-FF Century Tower Kalma 11 00007 Services 3399015-8 Mrs.Shazia Suleman 35201-4916449-8 Tours Chowk Lahore 157/8 Main Ferozepur Road, 12 00008 U & I Manufacturer New Wahdat Road More 0893806- Mrs. -

Home-Based Workers by Martha Alter Chen April 2014

Informal Economy Monitoring Study Sector Report: Home-Based Workers by Martha Alter Chen April 2014 Informal Economy IEMS Monitoring Study Informal Economy Monitoring Study Sector Report: Home-Based Workers Author Martha (Marty) Alter Chen is a co-founder and the International Coordinator of WIEGO, as well as a Lecturer in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, and an Affiliated Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. An experienced development practitioner and scholar, Marty’s areas of specialization are employment, gender, and poverty with a focus on the working poor in the informal economy. Acknowledgements Special thanks are due to the local research partners and research teams in each city whose knowledge of home- based workers and their respective cities were so critical to the success of the Informal Economy Monitoring Study. In Ahmedabad, the research partner was the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA). Manali Shah, Mansi Shah, and Shalini Trivedi from the SEWA Union coordinated the study. The local research team from CEPT University were Darshini Mahadevia, Aseem Mishra, and Suchita Vyas. In Bangkok, the research partner was HomeNet Thailand. Suanmuang (Poonsap) Tulaphan of HomeNet Thailand coordinated the research and served as one of the qualitative researchers and MBO representatives. The local research team consisted of Sayamol Charoenratan, Amornrat Kaewsing, Boonsom Namsomboon, Chidchanok Samantrakul, and Suanmuang Tulaphan. In Lahore, the research partner was HomeNet Pakistan, represented by Ume-Laila Azhar who coordinated the research. The local research team were Bilal Naqeeb, Rubina Saigol, Kishwar Sultana, and Reema Kamal. Special thanks are also due to Caroline Moser, Angélica Acosta, and Irene Vance who helped design the qualitative tools and train the local research teams. -

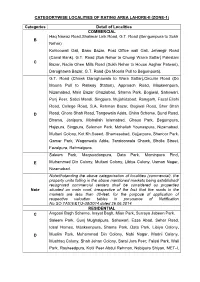

Categorywise Localities of Rating Area Lahore-Ii (Zone-1)

CATEGORYWISE LOCALITIES OF RATING AREA LAHORE-II (ZONE-1) Categories Detail of Localities COMMERCIAL Haq Nawaz Road,Shalimar Link Road, G.T. Road (Bengumpura to Sukh B Nehar) Kohloowali Gali, Bano Bazar, Post Office wali Gali, Jehangir Road (Canal Bank), G.T. Road (Suk Nehar to Chungi Warra Sattar) Pakistani C Bazar, Nadia Ghee Mills Road (Sukh Nehar to House Asghar Patwari), Daroghawla Bazar, G.T. Road (Do Mooria Pull to Begumpura). G.T. Road (Chowk Daroghawala to Wara Sattar),Circular Road (Do Mooria Pull to Railway Station), Approach Road, Maskeenpura, Nizamabad, Main Bazar Ghaziabad, Shama Park, Bogiwal, Sahowari, Punj Peer, Sabzi Mandi, Singpura, Mujahidabad, Ramgarh, Fazal Ellahi Road, College Road, S.A. Rehman Bazar, Bogiwal Road, Sher Shah D Road, Ghore Shah Road, Tangewala Adda, China Scheme, Bund Road, Bhama, Janipura, Mohallah Islamabad, Ghaus Park, Begumpura, Hajipura, Singpura, Suleman Park, Mohallah Younaspura, Nizamabad, Multani Colony, Kot Kh.Saeed, Shamasabad, Gujjarpura, Shanoor Park, Qamar Park, Wagonwala Adda, Tandoorwala Chowk, Bholla Street, Fazalpura, Rehmatpura. Saleem Park, Maqsoodanpura, Data Park, Mominpura Pind, E Muhammad Din Colony, Multani Colony, Libiya Colony, Usman Nagar, Nizamabad. Notwithstanding the above categorization of localities (commercial), the property units falling in the above mentioned markets being established/ recognized commercial centers shall be considered as properties Note situated on main road, irrespective of the fact that the roads in the markets are less than 30-feet, for the purpose of application of respective valuation tables in pursuance of Notification No.SO.TAX(E&T)3-38/2014 dated 26.06.2014. RESIDENTIAL C Angoori Bagh Scheme, Inayat Bagh, Mian Park, Surraya Jabeen Park. -

HCAR CDC LIST AS on MARCH 21, 2018 Sr No Member Folio Parid

HCAR CDC LIST AS ON MARCH 21, 2018 Sr No Member Folio ParID CDC A/C # SHARE HOLDER'S NAME ADDRESS 1 CDC-1 00208 30 ALFA ADHI SECURITIES (PVT) LTD. SUITE NO. 303, 3RD FLOOR, MUHAMMAD BIN QASIM ROAD, I.I. CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI 2 CDC-2 00208 3075 Rafiq III-F, 13/7, NAZIMABAD NO. 3, 74600 KARACHI 3 CDC-3 00208 3729 Omar Farooq HOUSE NO B-144, BLOCK-3, GULISTAN-E-JOUHAR KARACHI 4 CDC-4 00208 7753 AFSHAN SHAKIL A-82, S.B.C.H.S. BLOCK 12, GULISTAN-E-JAUHAR KARACHI 5 CDC-5 00208 8827 SARWAR DIN L-361, SHEERIN JINNAH COLONY , CLIFTON KARACHI 6 CDC-6 00208 11805 SHUNIL KUMAR OFFICE # 105,HUSSAIN TRADE CENTER, ALTAF HUSSAIN ROAD, NEW CHALI KARACHI 7 CDC-7 00208 12126 ABDUL SAMAD D-9, DAWOOD COLONY, SHARFABAD, NEAR T.V. STATION. KARACHI 8 CDC-8 00208 18206 Syeda Sharmeen Flat # 506, Ana Classic Apartment, Ghulam Hussain Qasim Road, Garden West KARACHI 9 CDC-9 00208 18305 Saima Asif FLAT NO: 306, MOTIWALA APARTMENT, PLOT NO: BR 5/16, MULJI STREET, KHARADHAR KARACHI 10 CDC-10 00208 18511 Farida FLAT NO: 306, MOTIWALA APARTMENT, PLOT NO: BR 5/16, MULJI STREET, KHARADHAR, KARACHI 11 CDC-11 00208 19626 MANOHAR LAL MANOHAR EYE CLINIC JACOBABAD 12 CDC-12 00208 21945 ADNAN FLAT NO 101, PLOT NO 329, SIDRA APPARTMENT, GARDEN EAST, BRITTO ROAD, KARACHI 13 CDC-13 00208 25672 TAYYAB IQBAL FLAT NO. 301, QASR-E-GUL, NEAR T.V. STATION, JAMAL-UD-DIN AFGHANI ROAD, SHARFABAD KARACHI 14 CDC-14 00208 26357 MUHAMMAD SALEEM KHAN G 26\9,LIAQUAT SQUARE, MALIR COLONY, KARACHI 15 CDC-15 00208 27165 SABEEN IRFAN 401,HEAVEN PRIDE,BLOCK-D, FATIMA JINNAH COLONY,JAMSHED ROAD#2, KARACHI 16 CDC-16 00208 27967 SANA UL HAQ 3-F-18-4, NAZIMABAD KARACHI 17 CDC-17 00208 29112 KHALID FAREED SONIA SQUARE, FLAT # 05, STADIUM ROAD, CHANDNI CHOWK, KARACHI 5 KARACHI 18 CDC-18 00208 29369 MOHAMMAD ZEESHAN AHMED FLAT NO A-401, 4TH FLOOR, M.L GARDEN PLOT NO, 690, JAMSHED QUARTERS, KARACHI 19 CDC-19 00208 30151 SANIYA MUHAMMAD RIZWAN HOUSE # 4, PLOT # 3, STREET# 02, MUSLIMABAD, NEAR DAWOOD ENGG. -

ICI PAKISTAN LIMITED Interim Dividend 78 (50%) List of Shareholders Whose CNIC Not Available with Company for the Year Ending June 30, 2015

ICI PAKISTAN LIMITED Interim Dividend 78 (50%) List of Shareholders whose CNIC not available with company for the year ending June 30, 2015 S.NO. FOLIO NAME ADDRESS Net Amount 1 47525 MS ARAMITA PRECY D'SOUZA C/O AFONSO CARVALHO 427 E MYRTLE CANTON ILL UNITED STATE OF AMERICA 61520 USA 1,648 2 53621 MR MAJID GANI 98, MITCHAM ROAD, LONDON SW 17 9NS, UNITED KINGDOM 3,107 3 87080 CITIBANK N.A. HONG KONG A/C THE PAKISTAN FUND C/O CITIBANK N.A.I I CHUNDRIGAR RD STATE LIFE BLDG NO. 1, P O BOX 4889 KARACHI 773 4 87092 W I CARR (FAR EAST) LTD C/O CITIBANK N.A. STATE LIFE BUILDING NO.1 P O BOX 4889, I I CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI 310 5 87147 BANKERS TRUST CO C/O STANDARD CHARTERED BANK P O BOX 4896 I I CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI 153 6 10 MR MOHAMMAD ABBAS C/O M/S GULNOOR TRADING CORPORATION SAIFEE MANZIL ALTAF HUSAIN ROAD KARACHI 64 7 13 SAHIBZADI GHULAM SADIQUAH ABBASI FLAT NO.F-1-G/1 BLOCK-3 THE MARINE BLESSINGS KHAYABAN-E-SAADI CLIFTON KARACHI 2,979 8 14 SAHIBZADI SHAFIQUAH ABBASI C/O BEGUM KHALIQUAH JATOI HOUSE NO.17, 18TH STREET KHAYABAN-E-JANBAZ, PHASE V DEFENCE OFFICERS HOUSING AUTHO KARACHI 892 9 19 MR ABDUL GHAFFAR ABDULLAH 20/4 BEHAR COLONY 2ND FLOOR ROOM NO 5 H ROAD AYESHA BAI MANZIL KARACHI 21 10 21 MR ABDUL RAZAK ABDULLA C/O MUHAMMAD HAJI GANI (PVT) LTD 20/13 NEWNAHM ROAD KARACHI 234 11 30 MR SUBHAN ABDULLA 82 OVERSEAS HOUSING SOCIETY BLOCK NO.7 & 8 KARACHI 183 12 50 MR MOHAMED ABUBAKER IQBAL MANZIL FLAT NO 9 CAMPBELL ROAD KARACHI 3,808 13 52 MST HANIFA HAJEE ADAM PLOT NO 10 IST FLOOR MEGHRAJ DUWARKADAS BUILDING OUTRAM ROAD NEAR PAKISTAN -

A Study of the Conservation Significance of Pirzada Mansion, Lahore, Pakistan

A STUDY OF THE CONSERVATION SIGNIFICANCE OF PIRZADA MANSION, LAHORE, PAKISTAN A. M. Malik* M. Rashid** S. S. Haider*** A. Jalil**** ABSTRACT 1050, which shows that its existence was due to its placement along the major trade route through Central Asia and the Built heritage is not merely about living quarters, but it Indian subcontinent. The city was regularly marred by also reflects the living standards, cultural norms and values invasion, pillage, and destruction (due to its lack of of any society. The old built heritage gives references to the geographical defenses and general over exposure) until past, the way people used to live and their living 1525, when it was sacked and then settled by the Mughal arrangements. This is done by understanding the spatial emperor Babur. Sixty years later it became the capital of the layouts of that particular built heritage. This research aims Mughal Empire under Akbar, and in 1605 the Fort and city to focus on documenting a historic building from the colonial walls were expanded to the present day dimensions. From period located in the walled city of Lahore, to highlight the the mid-18th century until British colonial times, there was need and significance of conservation of these historical a fairly lawless period in which most of the Mughal Palaces buildings that are neglected and under threat. The method (havelis) were destroyed, marking a decrease in social norms of research adopted for this paper was to document this and association with the built environment, that has continued building via an ethnographic analysis using photographic unabattingly till today. -

Andheroon Shehr by Neiha Lasharie

Andheroon Shehr by Neiha Lasharie The Heart of Pakistan. Along the perennially tense border between India and Pakishan lies a city so old its beginnings are lost to myth and legend; the historic capital of the land of Five Rivers, the province Punjab. Some legends, such as those in the Ramayana epic, suggest Lahore was known in olden days as Lavapuri, founded by Prince Lava, a son of the Hindu god and goddess Rama and Sita; other historical accounts of the city date back to the 1st Century AD, where it is referred to as Labokla. But whether two thousand years old, or 4000 years old, Lahore is a city unlike any other, a testament to the glory of truly organic, truly city-cities. So perhaps it is a little jarring that you arrive in Lahore the way anyone would to a big city in this day and age. Navigating your way though Allama Iqbal International Airport, you can see the city lights in the distance, but first you attempt to get out of the airport. Gently - and then slightly more forcefully - you shrug off the laymen-porters' offers to load up a taxi with your luggage. You look back at the airport, in its vaguely modern glory, and note the inherent Mughal influences - Lahore can't seem to divorce itself from that part of its history. Allama Iqbal International Airport, named after the poet-philosopher Sir Muhammad Iqbal, one of the visionaries behind what is now Pakistan. I have visited his grave before, a red brick structure in the Old City of Lahore, within what is called the Lahore Fort. -

A Historic Journey of the Lahore City, to Attain Its Identity Through Architecture

ISSN 2411-958X (Print) European Journal of May-August 2017 ISSN 2411-4138 (Online) Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 3, Issue 3 A Historic Journey of the Lahore City, to Attain Its Identity through Architecture Najma Kabir Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, University of South Asia, Lahore, Pakistan Ghulam Abbas Prof. Department of Architecture and Planning, University of Engineering & Technology Lahore, Pakistan Khizar Hayat Director Design, Central Design Office (WATER) Water and Power Development Authority, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract Lahore is a historical and the second largest city of Pakistan. It has a unique geographical location as it is located on the main trade and invasion routes to South Asia. Its history dates back to 1000BC, when its foundations were laid by the Hindu prince Loh, son of Rama Chandra. After the invasion of Mahmud of Ghazni in 1000AD, the city of Lahore has grown, flourished, suffered invasions and destruction, and yet survived through the Sultanate (1206-1524), the Mughal (1524-1712) and Sikh (1764-1849) periods with an uneven, yet unbroken, cultural evolution. This is evident in the form of monuments and artefacts that developed and evolved over time. The research paper discusses how architecture and contemporary arts in Lahore developed with time through the examples of representative buildings as case studies. It also discusses the impacts of cultural, religious and social factors on the art and architecture during different rules and how they are embodied in the city of Lahore to contribute towards its unique identity. The Mughals, who ruled for almost three centuries, were famous as great builders. They laid the infrastructure of Lahore and built finest architectural monuments. -

Growth Diagnostic of Pakistan

DECEMBER 2020 Growth Diagnostic of Pakistan There's no need to wait Start to create An exclusive Interview with Arshad Zaman PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is the oldest political foundation in Germany. The foundation is named after Friedrich Ebert, the first democratically elected president of Germany. The Friedrich Ebert Stiftung established its Pakistan Office in 1990. FES focuses on enhancing dialogue for mutual understanding and peaceful development in its international work. Social justice in politics, the economy and in the society is one of our leading principles worldwide. FES operates 107 offices in nearly as many countries. In Pakistan, FES has been cooperating with governmental institutions, civil society, and academic organizations and carrying out activities; To strengthen democratic culture through deliberative processes and informed public discourse; To promote and advocate social justice as an integral part of economic development through economic reforms and effective labor governance; To enhance regional cooperation for peace and development Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES), but exclusively of the author(s). For more information about FES, visit us at: Website: http://www.fes-pakistan.org Facebook: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Pakistan Twitter @FES_PAK www.pide.org.pk [email protected] +92 51 924 8051 +92 51 942 8065 Disclaimer: PIDE Policy & Research is a guide to policy making and research. The views expressed by the Each issue focuses on a particular theme, but also provides a contributors do not reflect general insight into the Pakistani economy, identifies key areas of the official perspectives of concern for policymakers, and suggests policy action.