Economic Change and Community Relations in Lahore Before Partition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Un-Paid Dividend

Descon Oxychem Limited DETAIL OF UNPAID DIVIDEND AMOUNT(S) IN PKR Dated as on: 18-Dec-20 Folio Shareholder Adresses No. of Shares Dividend 301, HAFSA SQUARE, BLOCK-3,, PLOT NO: 9, 208/32439/C ADAM KHALID MCHS., KARACHI-EAST, KARACHI 25,000 21,250 513/20972/C KHALID RAFIQUE MIRZA 5/6 B,PRESS COLONY G7/4 ISLAMABAD 20,000 17,000 B-13, SALMA VILLA, RUBY STREET,GARDEN 307/69264/C SHAN WEST, KARACHI 20,000 17,000 201 MR. AAMIR MALIK 115-BB, DHA, LAHORE. 25,500 15,300 18 MR. ABDUL KHALIQUE KHAN HOUSE NO.558/11, BLOCK W, DHA, LAHORE. 25,500 15,300 282 MR. SAAD ULLAH KHAN HOUSE NO.49/1, DHA, SECTOR 5, LAHORE. 20,000 12,000 269 MR. BILAL AHMAD BAJWA HOUSE NO.C-9/2-1485, KARAK ROAD, LAHORE. 20,000 12,000 HOUSE NO.258, SECTOR A1, TOWNSHIP, 105 MR. ATEEQ UZ ZAMAN KHAN LAHORE. 19,000 11,400 HOUSE NO.53-D, RIZWAN BLOCK, AWAN TOWN, 96 MR. AHMAD FAROOQ LAHORE. 19,000 11,400 HOUSE NO.42, LANE 3, ASKARIA COLONY, 103 MR. MUHAMMAD ANEES PHASE 1, MULTAN CANTT. 18,000 10,800 HOUSE NO.53/1, BLOCK C1, TOWNSHIP, 20 MR. MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD JAMEEL LAHORE. 18,000 10,800 6122/18275/C AHMAD HUSSAIN KAZI HOUSE # 100, HILLSIDE ROAD, E-7. ISLAMABAD 15,000 9,000 59 MR. ZUBAIR UL HASSAN HOUSE NO.10-22, ABID MAJID ROAD, LAHORE. 19,000 8,550 92 MR. ASAD AZHAR HOUSE NO.747-Z, DHA, LAHORE. 19,000 8,550 7161/42148/C MUHAMMAD KASHIF 50-G, BLOCK-2,P.E.C.H.S KARACHI 10,000 8,500 56, A-STREET, PHJASE 5, OFF KHAYABAN-E- 6700/23126/C HIBAH KHAN SHUJAAT D.H.A KARACHI 10,000 8,500 HOUSE # 164, ABUBAKAR BLOCK, GARDEN 12211/597/C JAVED AHMED TOWN, LAHORE 9,000 7,650 HOUSE # P-47 STREET # 4 JAIL ROAD RAFIQ 5801/16681/C MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COLONY FAISALABAD 9,000 7,650 FLAT # B-1, AL YOUSUF GARDEN,, GHULAM HUSSAIN QASIM ROAD, GARDEN WEST, 3277/77663/IIA IMRAN KARACHI 10,000 7,000 67 MR. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

'Skill Vs. Scale': the Transformation of Traditional Occupations in the Androon Shehr1

CHAPTER 16 ‘Skill vs. Scale’: The Transformation of Traditional Occupations in the Androon Shehr1 ALI KHAN, MANAL M. AHmaD, AND SANA F. MALIK INTRODUCTION eople often view the ‘Old City’ or Androon Shehr2 of Lahore as a ‘repository of memories and the past’, and a receptacle of cultural traditions and values. However, a walk down any of its crowded, winding streets reveals that the ‘historic core’3 of Lahore is not Psituated on any single plane—it is neither wholly ‘traditional’, nor wholly ‘modern’, neither old nor new, poor or rich, conservative or liberal. It is, in fact, heterotopic4—a synchronized product of conflicting elements. Heterotopia, or, in other words, dualism, is a structural characteristic of all Third World cities.5 That a dichotomy exists between an ‘indigenous’ culture and an ‘imposed’ Western culture in every postcolonial society is an established fact. This dichotomy is especially apparent in the economies of Third World cities—what Geertz has described as the ‘continuum’ between the ‘firm’ (formal) and ‘bazaar’ (informal) sectors.6 The Androon Shehr of Lahore is no exception; what makes the Shehr a particularly interesting study is that here the paradoxes of postcolonial society are more visible than anywhere else, as the Shehr, due to certain historic, physical and psychological factors, has managed to retain a ‘native’, pre-colonial identity that areas outside the ‘walls’ altogether lack, or have almost entirely lost, with the passage of time. This supposed ‘immunity’ of the Androon Shehr to the ‘disruption of the larger economic system’7 does not mean that the Shehr is a static, unchanging society—it simply means that the society has chosen to ‘modernize’8 on its own terms. -

DC Valuation Table (2018-19)

VALUATION TABLE URBAN WAGHA TOWN Residential 2018-19 Commercial 2018-19 # AREA Constructed Constructed Open Plot Open Plot property per property per Per Marla Per Marla sqft sqft ATTOKI AWAN, Bismillah , Al Raheem 1 Garden , Al Ahmed Garden etc (All 275,000 880 375,000 1,430 Residential) BAGHBANPURA (ALL TOWN / 2 375,000 880 700,000 1,430 SOCITIES) BAGRIAN SYEDAN (ALL TOWN / 3 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 SOCITIES) CHAK RAMPURA (Garision Garden, 4 275,000 880 400,000 1,430 Rehmat Town etc) (All Residential) CHAK DHEERA (ALL TOWN / 5 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIETIES) DAROGHAWALA CHOWK TO RING 6 500,000 880 750,000 1,430 ROAD MEHMOOD BOOTI 7 DAVI PURA (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) 275,000 880 350,000 1,430 FATEH JANG SINGH WALA (ALL TOWN 8 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) GOBIND PURA (ALL TOWNS / 9 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIEITIES) HANDU, Al Raheem, Masha Allah, 10 Gulshen Dawood,Al Ahmed Garden (ALL 250,000 880 350,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) JALLO, Al Hafeez, IBL Homes, Palm 11 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 Villas, Aziz Garden etc KHEERA, Aziz Garden, Canal Forts, Al 12 Hafeez Garden, Palm Villas (ALL TOWN 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) KOT DUNI CHAND Al Karim Garden, 13 Malik Nazir G Garden, Ghous Garden 250,000 880 400,000 1,430 (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) KOTLI GHASI Hanif Park, Garision Garden, Gulshen e Haider, Moeez Town & 14 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 New Bilal Gung H Scheme (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Al Wadood Garden (ALL 15 225,000 880 500,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Ring Road Par (ALL TOWN 16 75,000 880 200,000 -

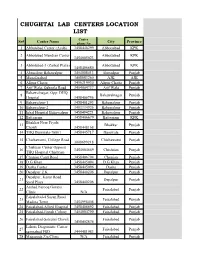

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

Consultancy Services for Urban Planning and Detailed Urban Design for Phase-1 of Ravi Riverfront Urban Development Project

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB EXPRESSION OF INTEREST CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR URBAN PLANNING AND DETAILED URBAN DESIGN FOR PHASE-1 OF RAVI RIVERFRONT URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Pre-Qualification Documents and Eligibility Criteria for the Selection of International Consulting Firms / Consortium / Joint Venture with Local Firms MAY 2021 RAVI URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ........................................................................................................................... 4 REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST DOCUMENT ............................................. 5 NOTICE INVITING REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION INTEREST ......................................... 6 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 7 i. Project Brief .................................................................................................................... 7 ii. Project Scope .................................................................................................................. 7 iii. Project Area .................................................................................................................... 7 iv. Map of Proposed Boundary of Phase-1 of RRUDP. ...................................................... 8 v. Rationale for the Study ................................................................................................... 9 vi. Tasks .............................................................................................................................. -

TH-- ECONOMIP RF}SCT8 Og TH I P'jn. 3AB CANAL COLON ' "God

07 TH-- ECONOMIPRF}SCT8 Og TH I P'JN.3AB CANAL COLON' "Ye can Know them from their dsel1tnRe, " . eý 4ýu'ý ýý, ýi sa.. ý . _, ,. ý "God has said, from water all thine are made. I son g(,vently ordain that this funkle in which mib- ei tense i'z obtained wire thirst be converted into a place of comfort** AYbarl .:3 KAPAR SINGH BAJWA, 5w>ý,. ý''.: aýý.: +a...... Rý.:..: - ýxý,:. ýrüýii'ýa: ý. yoaýa: s, +. _.: ý. - .; ý; , wir' -ý`°'°--; "v. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Variable print quality CONTAINS PULLOUTS (1) 1 PRR7A0 To readers interested in the material progroas of the Province, no introduction zooms necessary for no fascinating, a subject as the "Enonoiio oftoota of the Punjab Fanal development of the Canal Poloniee. " The origin, .roath and colonies in an interesting and surprising; miracle or the 20th century -a miracle which has given rise to an Important trading city litt© Iyaulpur, the capital of the Lower Chonab Colony. T' e development of the Lower Bari Toab Colo yº has an Importance of its own as it ie the youngest of all its sister colonies and as most or us have soon the change that has come over the now Par* One can see what it wns like loss than ten years ago an one passes in the Karachi Mail through the desert skirting the youngest Canal Colon; yq not. a vestige of cultivation on either aide: only sand hills and a barren plaint dreariness unroolaimod save by the vivid tiiraie of water and trees. How this blight and hideousness of land, wao redeemed by the miracle of the 20th century and what are tho consequences of this change form the scope or shy thesis. -

Second Lahore Biennale: Between the Sun and the Moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists

For Immediate Release 6 January 2020 Second Lahore Biennale: between the sun and the moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists Installed Across Cultural and Heritage Sites Throughout Lahore, Pakistan, from 26 January to 29 February 2020 Lahore, Pakistan—6 January 2020—The Lahore Biennale Foundation today revealed a list of over 70 participating artists for the second edition of the Lahore Biennale (LB02), running from 26 January through 29 February 2020. Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, LB02: between the sun and the moon brings a plethora of artistic projects to cultural and heritage sites throughout the city of Lahore including more than 20 new commissions by artists from across the region and around the world, including Alia Farid, Diana Al-Hadid, Hassan Hajjaj, Haroon Mirza, Hajra Waheed and Simone Fattal, among many others. Other participating artists include Anwar Saeed, Rasheed Araeen and the late Madiha Aijaz. With a focus on the Global South, where ongoing social disaffection is being aggravated by climate change, LB02 responds to the cultural and ecological history of Lahore and aims to awaken awareness of humanity’s daunting contemporary predicament. Works presented in LB02 will explore human entanglement with the environment while revisiting traditional understandings of the self and their cosmological underpinnings. Inspiration for this thematic focus is drawn from intellectual and cultural exchange between South and West Asia. “For centuries, inhabitants of these regions oriented themselves with reference to the sun, the moon, and the constellations. -

![C$) *!! Tc UVWV TV UVR] @< U](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1347/c-tc-uvwv-tv-uvr-u-801347.webp)

C$) *!! Tc UVWV TV UVR] @< U

6 7 > 3 *! ? )! ? ? RNI Regn. No. CHHENG/2012/42718, Postal Reg. No. - RYP DN/34/2013-2015 .0!:.",23 1#-#-8 "+ (1/0$ B -""4"" 64363" C4; 1"C4,." 3"6-6.4=5 1-=61-14"5; 5 -4 3"4".66 6" /$ ,44";- =;C ;4-;; -43,;- 3"-;34 -C3";13DC53 @6 +(90..# /#/ @ ) " * 5*1818; ,15 4"53"6- about the other deals given the Pinaka missile systems will + 4"53"6- " # !$ go-ahead, officials said weapon enable raising additional mid volatile situation on systems and equipment will be regiments over and above the fter a spooky June that saw & '(!) Athe Line of Actual Control manufactured in India involv- ones already inducted by the Aa three-fold rise in Covid- (LAC) in Ladakh, the Defence ing Indian defence industry Army. 19 cases from 2 lakh to 6 lakh, Acquisition Council (DAC) with participation of several India’s doubling rate — a glob- chaired by Defence Minister Micro, Small and Medium ally adopted yardstick to gauze Rajnath Singh on Thursday Enterprises (MSME). the acceleration of the outbreak approved defence deals worth “The Indigenous content in — stands fastest among the first over 38,900 crore. They some of these projects is up to 15 worst-affected countries. include acquisition of 33 front- 80 per cent of the project cost. In simple terms, the num- line fighter jets besides missiles A large number of these pro- ber of cases is rising much and ammunition. jects have been made possible faster in India than other worst- The approvals for procur- ed cost of 10,730 crore,” meant to replace the aircraft due to Transfer of Technology ! affected nations. -

Here in the United Online Premieres Too

Image : Self- portrait by Chila Kumari Singh Burman Welcome back to the festival, which this Dive deep into our Extra-Ordinary Lives strand with amazing dramas and year has evolved into a hybrid festival. documentaries from across South Asia. Including the must-see Ahimsa: Gandhi, You can watch it in cinemas in London, The Power of The Powerless, a documentary on the incredible global impact of Birmingham, and Manchester, or on Gandhi’s non-violence ideas; Abhijaan, an inspiring biopic exploring the life of your own sofa at home, via our digital the late and great Bengali actor Soumitra Chatterjee; Black comedy Ashes On a site www.LoveLIFFatHome.com, that Road Trip; and Tiger Award winner at Rotterdam Pebbles. Look out for selected is accessible anywhere in the United online premieres too. Kingdom. Our talks and certain events We also introduce a new strand dedicated to ecology-related films, calledSave CARY RAJINDER SAWHNEY are also accessible worldwide. The Planet, with some stirring features about lives affected by deforestation and rising sea levels, and how people are meeting the challenge. A big personal thanks to all our audiences who stayed with the festival last We are expecting a host of special guests as usual and do check out our brilliant year and helped make it one of the few success stories in the film industry. This online In Conversations with Indian talent in June - where we will be joined year’s festival is dedicated to you with love. by Bollywood Director Karan Johar, and rapidly rising talented actors Shruti Highlights of this year’s festival include our inspiring Opening Night Gala Haasan and Janhvi Kapoor, as well as featuring some very informative online WOMB about one woman gender activist who incredibly walks the entire Q&As on all our films. -

Archaeology Below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: the Mughal Underground Chambers

Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan: The Mughal Underground Chambers Prepared by Rustam Khan For Global Heritage Fund Preservation Fellowship 2011 Acknowledgements: The author thanks the Director and staff of Lahore Fort for their cooperation in doing this report. Special mention is made of the photographer Amjad Javed who did all the photography for this project and Nazir the draughtsman who prepared the plans of the Underground Chambers. Map showing the location of Lahore Walled City (in red) and the Lahore Fort (in green). Note the Ravi River to the north, following its more recent path 1 Archaeology below Lahore Fort, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Pakistan 1. Background Discussion between the British Period historians like Cunningham, Edward Thomas and C.J Rodgers, regarding the identification of Mahmudpur or Mandahukukur with the present city of Lahore is still in need of authentic and concrete evidence. There is, however, consensus among the majority of the historians that Mahmud of Ghazna and his slave-general ”Ayyaz” founded a new city on the remains of old settlement located some where in the area of present Walled City of Lahore. Excavation in 1959, conducted by the Department of Archaeology of Pakistan inside the Lahore Fort, provided ample proof to support interpretation that the primeval settlement of Lahore was on this mound close to the banks of River Ravi. Apart from the discussion regarding the actual first settlement or number of settlements of Lahore, the only uncontroversial thing is the existence of Lahore Fort on an earliest settlement, from where objects belonging to as early as 4th century AD were recovered during the excavation conducted in Lahore Fort .