Andheroon Shehr by Neiha Lasharie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Skill Vs. Scale': the Transformation of Traditional Occupations in the Androon Shehr1

CHAPTER 16 ‘Skill vs. Scale’: The Transformation of Traditional Occupations in the Androon Shehr1 ALI KHAN, MANAL M. AHmaD, AND SANA F. MALIK INTRODUCTION eople often view the ‘Old City’ or Androon Shehr2 of Lahore as a ‘repository of memories and the past’, and a receptacle of cultural traditions and values. However, a walk down any of its crowded, winding streets reveals that the ‘historic core’3 of Lahore is not Psituated on any single plane—it is neither wholly ‘traditional’, nor wholly ‘modern’, neither old nor new, poor or rich, conservative or liberal. It is, in fact, heterotopic4—a synchronized product of conflicting elements. Heterotopia, or, in other words, dualism, is a structural characteristic of all Third World cities.5 That a dichotomy exists between an ‘indigenous’ culture and an ‘imposed’ Western culture in every postcolonial society is an established fact. This dichotomy is especially apparent in the economies of Third World cities—what Geertz has described as the ‘continuum’ between the ‘firm’ (formal) and ‘bazaar’ (informal) sectors.6 The Androon Shehr of Lahore is no exception; what makes the Shehr a particularly interesting study is that here the paradoxes of postcolonial society are more visible than anywhere else, as the Shehr, due to certain historic, physical and psychological factors, has managed to retain a ‘native’, pre-colonial identity that areas outside the ‘walls’ altogether lack, or have almost entirely lost, with the passage of time. This supposed ‘immunity’ of the Androon Shehr to the ‘disruption of the larger economic system’7 does not mean that the Shehr is a static, unchanging society—it simply means that the society has chosen to ‘modernize’8 on its own terms. -

DC Valuation Table (2018-19)

VALUATION TABLE URBAN WAGHA TOWN Residential 2018-19 Commercial 2018-19 # AREA Constructed Constructed Open Plot Open Plot property per property per Per Marla Per Marla sqft sqft ATTOKI AWAN, Bismillah , Al Raheem 1 Garden , Al Ahmed Garden etc (All 275,000 880 375,000 1,430 Residential) BAGHBANPURA (ALL TOWN / 2 375,000 880 700,000 1,430 SOCITIES) BAGRIAN SYEDAN (ALL TOWN / 3 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 SOCITIES) CHAK RAMPURA (Garision Garden, 4 275,000 880 400,000 1,430 Rehmat Town etc) (All Residential) CHAK DHEERA (ALL TOWN / 5 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIETIES) DAROGHAWALA CHOWK TO RING 6 500,000 880 750,000 1,430 ROAD MEHMOOD BOOTI 7 DAVI PURA (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) 275,000 880 350,000 1,430 FATEH JANG SINGH WALA (ALL TOWN 8 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) GOBIND PURA (ALL TOWNS / 9 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIEITIES) HANDU, Al Raheem, Masha Allah, 10 Gulshen Dawood,Al Ahmed Garden (ALL 250,000 880 350,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) JALLO, Al Hafeez, IBL Homes, Palm 11 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 Villas, Aziz Garden etc KHEERA, Aziz Garden, Canal Forts, Al 12 Hafeez Garden, Palm Villas (ALL TOWN 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) KOT DUNI CHAND Al Karim Garden, 13 Malik Nazir G Garden, Ghous Garden 250,000 880 400,000 1,430 (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) KOTLI GHASI Hanif Park, Garision Garden, Gulshen e Haider, Moeez Town & 14 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 New Bilal Gung H Scheme (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Al Wadood Garden (ALL 15 225,000 880 500,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Ring Road Par (ALL TOWN 16 75,000 880 200,000 -

Eid-Ul-Adha Plan

Eid ul Adha Plan 2017 Page 0 PREFACE This is LWMC’s Eid-ul-Azha plan 2017. This plan will cover detailed information regarding Solid Waste Management (SWM) services, which shall be provided by LWMC during Eid days. LWMC is going to make special arrangements for Solid Waste Management (SWM) on the eve of Eid-ul-Azha. LWMC in coordination with Turkish Contractors (M/s. Albayrak & M/s. Ozpak) will attempt to offer exemplary cleanliness arrangements on the eve of Eid-ul-Azha. The standard SWM activities will mainly focus on prompt collection, storage, transportation and disposal of animal waste during all three days of Eid. All the staff of LWMC will remain on board during Eid days to provide efficient SWM services to the citizens of Lahore. LWMC will establish Eid Camps in each Union Council of Lahore, not only to address the complaints of the citizens but to efficiently coordinate cleanliness activities in the respective UC’s as well. Moreover, awareness material and garbage bags for animal waste will also be available in these camps. A control room will be established in LWMC head office with special focus to coordinate collective operational activities during Eid days. In order to manage animal waste, LWMC is going to distribute 2 Million garbage bags in Lahore. The garbage bags will be made available free of cost in respective UC Camps / Zonal Office, Major Masajids / Eid Gahs. Similarly, for prompt collection of animal waste, LWMC will hire pickups 2 days before Eid for garbage bag distribution, awareness & waste collection. 1089 pickups will be hired on first day, 1025 on second and 543 on third day of Eid. -

Old-City Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts

Bāzyāft-31 (Jul-Dec 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 21 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Amjad Parvez ABSTRACT: Lahore has been known as a crucible of diversified cultures owing to its nature of being a trade center, as well as being situated on the path to the capital city Delhi. Both consumers and invaders, played their part in the acculturation of this city from ancient times to the modern era.This research paperinvestigates the existing as well as the vanishing popular culture of the Old-city Lahore. The cuisine, crafts, kites, music, painting and couture of Lahore advocate the assimilation of varied tastes, patterns and colours, with dissimilar origins, within the narrow streets of the Old- city. This document will cover the food, vendors, artisans, artists and the red-light area, not only according to their locations and existence, butin terms of cultural relations too.The paper also covers the distinct standing of Lahore in the South Asia and its popularity among, not only its inhabitants, but also those who ever visited Lahore. Introduction The Old City of Lahore is characterized by the diversity of cultures that is due tovarious invaders and ruling dynasties over the centuries. The narrow streets, dabbed patches of light andunmatched cuisine add to the colours, fragrance and panorama of this unique place. 22 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Figure 1. “Old-city Lahore Street” (2015) By Amjad Parvez Digital Photograph Personal Collection Inside the Old-city Lahore, one may come the steadiness and stationary quality of time, or even one could feel to have been travelled backward in the two or three centuries when things were hand-made, and the culture was non-metropolitan. -

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

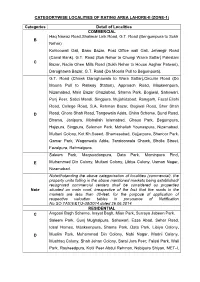

Categorywise Localities of Rating Area Lahore-Ii (Zone-1)

CATEGORYWISE LOCALITIES OF RATING AREA LAHORE-II (ZONE-1) Categories Detail of Localities COMMERCIAL Haq Nawaz Road,Shalimar Link Road, G.T. Road (Bengumpura to Sukh B Nehar) Kohloowali Gali, Bano Bazar, Post Office wali Gali, Jehangir Road (Canal Bank), G.T. Road (Suk Nehar to Chungi Warra Sattar) Pakistani C Bazar, Nadia Ghee Mills Road (Sukh Nehar to House Asghar Patwari), Daroghawla Bazar, G.T. Road (Do Mooria Pull to Begumpura). G.T. Road (Chowk Daroghawala to Wara Sattar),Circular Road (Do Mooria Pull to Railway Station), Approach Road, Maskeenpura, Nizamabad, Main Bazar Ghaziabad, Shama Park, Bogiwal, Sahowari, Punj Peer, Sabzi Mandi, Singpura, Mujahidabad, Ramgarh, Fazal Ellahi Road, College Road, S.A. Rehman Bazar, Bogiwal Road, Sher Shah D Road, Ghore Shah Road, Tangewala Adda, China Scheme, Bund Road, Bhama, Janipura, Mohallah Islamabad, Ghaus Park, Begumpura, Hajipura, Singpura, Suleman Park, Mohallah Younaspura, Nizamabad, Multani Colony, Kot Kh.Saeed, Shamasabad, Gujjarpura, Shanoor Park, Qamar Park, Wagonwala Adda, Tandoorwala Chowk, Bholla Street, Fazalpura, Rehmatpura. Saleem Park, Maqsoodanpura, Data Park, Mominpura Pind, E Muhammad Din Colony, Multani Colony, Libiya Colony, Usman Nagar, Nizamabad. Notwithstanding the above categorization of localities (commercial), the property units falling in the above mentioned markets being established/ recognized commercial centers shall be considered as properties Note situated on main road, irrespective of the fact that the roads in the markets are less than 30-feet, for the purpose of application of respective valuation tables in pursuance of Notification No.SO.TAX(E&T)3-38/2014 dated 26.06.2014. RESIDENTIAL C Angoori Bagh Scheme, Inayat Bagh, Mian Park, Surraya Jabeen Park. -

A Study of the Conservation Significance of Pirzada Mansion, Lahore, Pakistan

A STUDY OF THE CONSERVATION SIGNIFICANCE OF PIRZADA MANSION, LAHORE, PAKISTAN A. M. Malik* M. Rashid** S. S. Haider*** A. Jalil**** ABSTRACT 1050, which shows that its existence was due to its placement along the major trade route through Central Asia and the Built heritage is not merely about living quarters, but it Indian subcontinent. The city was regularly marred by also reflects the living standards, cultural norms and values invasion, pillage, and destruction (due to its lack of of any society. The old built heritage gives references to the geographical defenses and general over exposure) until past, the way people used to live and their living 1525, when it was sacked and then settled by the Mughal arrangements. This is done by understanding the spatial emperor Babur. Sixty years later it became the capital of the layouts of that particular built heritage. This research aims Mughal Empire under Akbar, and in 1605 the Fort and city to focus on documenting a historic building from the colonial walls were expanded to the present day dimensions. From period located in the walled city of Lahore, to highlight the the mid-18th century until British colonial times, there was need and significance of conservation of these historical a fairly lawless period in which most of the Mughal Palaces buildings that are neglected and under threat. The method (havelis) were destroyed, marking a decrease in social norms of research adopted for this paper was to document this and association with the built environment, that has continued building via an ethnographic analysis using photographic unabattingly till today. -

Accurate but Incomplete

Preliminary Electoral Rolls 2012 ACCURATE BUT INCOMPLETE An Assessment of Voter Lists Displayed for Public Scrutiny in March 2012 13% Voters not Verified in Areas of their Residence 20 Million Potentially Missing on Rolls ir Electio a n F N & e t w e e o r r k F FAFEN Free and Fair Election Network www.fafen.org Free and Fair Election Network Preliminary Electoral Rolls 2012: Accurate But Incomplete All rights reserved. Any part of this publication may be produced or translated by duly acknowledging the source. 1st Edition: June 2012. Copies 2,500 FAFEN is governed by the Trust for Democratic Education and Accountability (TDEA) TDEA-FAFEN Secretariat: 224-Margalla Road, F-10/3, Islamabad, Pakistan Email: [email protected] Website: www.fafen.org Twitter: @_FAFEN Table of Contents Acknowledgments i Abbreviations ii Executive Summary 2 Background 6 Methodology of Assessment of PER 2012 8 Key Findings 10 1. One in every eight voters not verified at his/her address given in PER 2012 10 2. Families of almost two thirds of unverified voters also not found on addresses given in PER 2012 10 3. More women than men voters not verified at residential addresses 11 4. One fifth of adult population potentially not registered as voters 11 5. Negligible number of voters misallocated 12 6. Voter entries on PER 2012 highly accurate 14 7. Quality of Display Period 15 7.1 Voter accessibility to display centers 15 7.2 Facilitation of voters at display centers 16 7.3 Materials available at display centers 17 7.4 Participation of women voters 18 7.5 Participation -

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: LAHORE, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE for RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17Th, 2014

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: LAHORE, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE FOR RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17th, 2014 Rains/Floods 2014: Lahore District Profile September 2014 iMMAP-USAID District at a Glance Administrative DivisionR ajanpur - Reference Map Police Stations (http://www.lahorepolice.gov.pk/) Attribute Value District/tehsil Knungo Patwar Number of Mouzas Sr. No. Police Station Phone No. Population (2014 est) 9,396,398 Circles/ Circles/ 1 SP Iqbal Town Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99230660 Male 4,949,706 (53%) Supervisory Tapas Total Rural Urban Partly Forest Un- 2 SP Iqbal Town Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092 42 99233331 Tapas urban populated Female 4,446,692 (47%) 3 Iqbal Town 0092 42 37801375 DISTRICT 22 213 360 211 92 40 17 4 SP Saddar Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99262023-4 Rural 1,650,134 (18%) LAHORE CITY 10 76 115 51 40 15 9 Urban 7,746,264 (82%) LAHORE 5 SP Saddar Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092 42 99262028-7 12 137 245 160 52 25 8 Tehsils 2 CANTT 6 Johar Town 0092 42 99231472 Towns & Cantonment 9 & 1 Source: Punjab Mouza Statistics 2008 7 SP Cantt. Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99220615/ 99221126 UC 165 8 SP Cantt. Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092-52-3553613 Road Network Infrastructure: District Roads: 1,244.41 (km), NHWs: 48.43 (km), Prov. Highways: Revenue Villages/Mouza 360 9 SP Model Town Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99263421-2 113.6 (km) R&B Sector: 245.31 (km), Farm to Market: 343.47 (km), District Council Roads: 493.6 (km) 10 SP Model Town (Inv. -

Sr. No College Name District Gender Division Contact 1 GOVT. COLLEGE for WOMEN, CHUNIAN, KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 494311934

Sr. College Name District Gender Division Contact No 1 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, CHUNIAN, KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 494311934 2 GOVT. CHANDO BEGUM DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, KANGANPUR, CHUNIAN KASUR Female LAHORE 424820777 3 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, ELLAHBAD, DISTRICT KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 4 GOVT. POST GRAUDATE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 492771477 5 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN KOT RADHA KISHAN, KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 492385268 Govt. Syed Charagh Shah Degree College for Women, Kot Murad Khan, District 6 KASUR Female LAHORE 492771999 Kasur 7 Govt.Hanifa Begum Degree College For Women Mustafabad,District Kasur KASUR Female LAHORE 8 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN KHUDIAN KHAS, KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 492790018 9 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN PATTOKI, KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 494420179 10 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN PHOOL NAGAR, KASUR KASUR Female LAHORE 494510398 11 GOVT. COLLEGE (BOYS) CHUNIAN, KASUR KASUR Male LAHORE 494311634 12 Govt. Institute of Commerce, Chunian KASUR Male LAHORE 494311150 13 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE MUSTAFA ABAD, KASUR KASUR Male LAHORE 492450518 14 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE (B) KOT RADHA KISHAN, KASUR KASUR Male LAHORE 492385525 15 GOVT. ISLAMIA COLLEGE KASUR KASUR Male LAHORE 492727861 16 Govt. College of Commerce, Kasur KASUR Male LAHORE 3049251951 17 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE, PATTOKI KASUR Male LAHORE 494420059 18 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE BHAI PHERU (PHOOL NAGAR), KASUR KASUR Male LAHORE 494510949 19 Govt. Institute of Commerce, Pattoki KASUR Male LAHORE 494427177 20 GOVT. COLLEGE TOWNSHIP LAHORE LAHORE Both LAHORE 4299262114 21 GOVT. COLLEGE OF SCIENCE WAHDAT ROAD LAHORE LAHORE Both LAHORE 4299260040 22 GOVT. ISLAMIA COLLEGE OF COMMERCE, LAHORE LAHORE Both LAHORE 4237808254 23 GOVT. -

Valuation Table Aziz Bhatti Town

VALUATION TABLE AZIZ BHATTI TOWN # AREA Residential 2017-18 Commercial 2017-18 Open Plot Per Registration Town Tax Total Open Plot Stamp Duty Registration Town Tax CVT 2% Stamp Duty 3% CVT 2% Total Tax Marla Fee 1% Tax Per Marla 3% Fee 1% 1 AL FAISAL TOWN 210000 4200 6300 200 2100 12800 510000 10200 15300 200 5100 30800 2 ALLAMA IQBAL ROAD 440000 8800 13200 200 4400 26600 980000 19600 29400 200 9800 59000 3 AMEER UD DIN PARK 220000 4400 6600 200 2200 13400 480000 9600 14400 200 4800 29000 4 AMIR TOWN 220000 4400 6600 200 2200 13400 480000 9600 14400 200 4800 29000 5 ARAAZI SEHJPAAL (EXCLUDING 240000 4800 7200 200 2400 14600 280000 5600 8400 200 2800 17000 D.H.A) 6 ARIF ABAD NEAR BEDIAN ROAD 125000 2500 3750 200 1250 7700 290000 5800 8700 200 2900 17600 7 BAHAR SHAH ROAD 190000 3800 5700 200 1900 11600 410000 8200 12300 200 4100 24800 8 BEDIAN ROAD, BHATTA CHOWK TO 200000 4000 6000 200 2000 12200 450000 9000 13500 200 4500 27200 OFFICE ELITE TOWN 9 BEDIAN ROAD R.A BAZAR TO 660000 13200 19800 200 6600 39800 660000 13200 19800 200 6600 39800 BHATTA CHOWK 10 BRIDGE COLONY 460000 9200 13800 200 4600 27800 950000 19000 28500 200 9500 57200 11 C.M.A COLONY 410000 8200 12300 200 4100 24800 950000 19000 28500 200 9500 57200 12 CANAL BANK ROAD, BOTH SIDES 470000 9400 14100 200 4700 28400 810000 16200 24300 200 8100 48800 13 CANAL PARK & NEW CANAL 250000 5000 7500 200 2500 15200 550000 11000 16500 200 5500 33200 14 CANTONMENT ROADS 600000 12000 18000 200 6000 36200 1000000 20000 30000 200 10000 60200 15 CHANDIAN 140000 2800 4200 200 1400 8600 350000 7000 10500 200 3500 21200 16 CHUNG KHURD (L.C.B). -

LIST of Mpas

04 October 2021 PPRROOVVIINNCCIIAALL AASSSSEEMMBBLLYY OOFF TTHHEE PPUUNNJJAABB LLIISSTT OOFF MMPPAAss www.pap.gov.pk E-mail: [email protected] Prepared by LEGISLATION SECTION 042-99204251 1 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY OF THE PUNJAB Assembly Exchange-PABX: 042-99200335-47 MPAs Hostel Exchange: 042-99200590-99 Pipals House Exchange: 042-99212761-70 OFFICERS OF THE HOUSE SPEAKER MR PARVEZ ELAHI House No.30-C, Zahoor Elahi Road, Gulberg-II, Lahore 042-99200311 (Off), 042-99200312 (Fax) 042-35712666, 042-35762666 (Res) DEPUTY SPEAKER SARDAR DOST MUHAMMAD MAZARI 2-Upper Mall, Lahore 042-99200313 (Off), 042-99200314 (Fax) 042-99201280, 042-99203655 (Res) 2 SECRETARY MR MUHAMMAD KHAN BHATTI 1-B, Club Road, GOR-I, Lahore 042-99200321, 042-99204244 (Off), 042-99200330 (Fax) 0341-8445500 DIRECTOR GENERAL (PA&R) MR INAYAT ULLAH LAK 84-B, GOR-II, Bahawalpur House, Mozang, Lahore 042-99200332 (Off), 042-35243050 (Res) 0300-4407510 DEPUTY SECRETARY (LEGISLATION) MR ALI HUSSNAIN BHALLI 126 Khushnuma GOR-IV, Model Town Extension, Lahore 042-99200323 (Off), 0321-6121007 3 CHIEF MINISTER PP-286 (PTI) Mr Usman Ahmed Khan Buzdar Chief Minister 8 Club Road, GOR-I, Lahore 042-99203228, 042-99203229 SENIOR MINISTER PP-158 (PTI) Mr Abdul Aleem Khan Minister for Food 55-C-II, Gulberg-III, Lahore 042-99204357 042-99203218 (Off), 042-99204357 (Fax), 0345-8444101 MINISTERS PP-1 (PTI) PP-4 (PTI) Syed Yawar Abbas Bukhari Malik Muhammad Anwar Minister for Social Welfare & Bait ul Maal Minister for Revenue PO Kamra, Attock (a) 108- New Minister Block, 0300-8505254 Punjab Civil Secretariat, Lahore (b) Tehsil Pindigheb, District Attock 042-99214745, 042-99214746 (Off), 0300-8428435 4 PP-14 (PTI) PP-21 (PTI) Mr Muhammad Basharat Raja Mr Yasir Humayun Minister for Law & Parliamentary Affairs, Minister for Higher Education Cooperatives (Addl.