The Chronicles Director Prof. Abdelaziz Ezzelarab Founding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt's Unsustainable Crackdown

MEMO POLICY EGYPT’S UNSUSTAINABLE CRACKDOWN Anthony Dworkin and Hélène Michou Six months after the army deposed Egypt’s first freely SUMMARY As a referendum on the constitution approaches, elected president, the new authorities are keen to give Egyptian authorities are keen to give the the impression that the country is back on the path to impression that the country is back on track democracy. A new constitution has been drafted and will towards democracy. But the government’s be put to a referendum in mid-January. Parliamentary apparent effort to drive the Muslim Brotherhood completely out of public life and the repression of and presidential elections are scheduled to follow within alternative voices mean that a political solution the following six months. Egypt’s interim president, Adly to the country’s divisions remains far off. While Mansour, described the draft constitution as “a good start on there are uncertainties about the path that Egypt which to build the institutions of a democratic and modern will follow, these will play out within limits set by state”.1 Amr Moussa, chairman of the committee of 50 that the country’s powerful security forces. Against a background of popular intolerance and public was largely responsible for writing the constitution, said that media that strongly back the state, there is little it marked “the transition from disturbances to stability and prospect of the clampdown being lifted in the from economic stagnation to development”.2 short term. Yet it would be wrong to believe that Egypt’s current However, this path seems to promise only further instability and turbulence. -

Arab Republic of Egypt

Egypt Country Profile ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT OFFICE OF COMMERCIAL AFFAIRS, ROYAL THAI EMBASSY, CAIRO THAI TRADE CENTER 1 Thai Trade Center, Cairo ٍ Sherif Yehya Egypt Country Profile Background: The regularity and richness of the annual Nile River flood, coupled with semi-isolation provided by deserts to the east and west, allowed for the development of one of the world's great civilizations. A unified kingdom arose circa 3200 B.C., and a series of dynasties ruled in Egypt for the next three millennia. The last native dynasty fell to the Persians in 341 B.C., who in turn were replaced by the Greeks, Romans, and Byzantines. It was the Arabs who introduced Islam and the Arabic language in the 7th century and who ruled for the next six centuries. A local military caste, the Mamluks took control about 1250 and continued to govern after the conquest of Egypt by the Ottoman Turks in 1517. Following the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, Egypt became an important world transportation hub, but also fell heavily into debt. Ostensibly to protect its investments, Britain seized control of Egypt's government in 1882, but nominal allegiance to the Ottoman Empire continued until 1914. Partially independent from the UK in 1922, Egypt acquired full sovereignty with the overthrow of the British- backed monarchy in 1952. The completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1971 and the resultant Lake Nasser have altered the time-honored place of the Nile River in the agriculture and ecology of Egypt. A rapidly growing population (the largest in the Arab world), limited arable land, and dependence on the Nile all continue to overtax resources and stress society. -

Alia Mossallam 200810290

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hikāyāt Sha‛b – Stories of Peoplehood Nasserism, Popular Politics and Songs in Egypt 1956-1973 Alia Mossallam 200810290 A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,397 words (excluding abstract, table of contents, acknowledgments, bibliography and appendices). Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that parts of my thesis were copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Naira Antoun. 2 Abstract This study explores the popular politics behind the main milestones that shape Nasserist Egypt. The decade leading up to the 1952 revolution was one characterized with a heightened state of popular mobilisation, much of which the Free Officers’ movement capitalized upon. Thus, in focusing on three of the Revolution’s main milestones; the resistance to the tripartite aggression on Port Said (1956), the building of the Aswan High Dam (1960- 1971), and the popular warfare against Israel in Suez (1967-1973), I shed light on the popular struggles behind the events. -

In May 2011, Freedom House Issued a Press Release Announcing the Findings of a Survey Recording the State of Media Freedom Worldwide

Media in North Africa: the Case of Egypt 10 Lourdes Pullicino In May 2011, Freedom House issued a press release announcing the findings of a survey recording the state of media freedom worldwide. It reported that the number of people worldwide with access to free and independent media had declined to its lowest level in over a decade.1 The survey recorded a substantial deterioration in the Middle East and North Africa region. In this region, Egypt suffered the greatest set-back, slipping into the Not Free category in 2010 as a result of a severe crackdown preceding the November 2010 parliamentary elections. In Tunisia, traditional media were also censored and tightly controlled by government while internet restriction increased extensively in 2009 and 2010 as Tunisians sought to use it as an alternative field for public debate.2 Furthermore Libya was included in the report as one of the world’s worst ten countries where independent media are considered either non-existent or barely able to operate and where dissent is crushed through imprisonment, torture and other forms of repression.3 The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Arab Knowledge Report published in 2009 corroborates these findings and view the prospects of a dynamic, free space for freedom of thought and expression in Arab states as particularly dismal. 1 Freedom House, (2011): World Freedom Report, Press Release dated May 2, 2011. The report assessed 196 countries and territories during 2010 and found that only one in six people live in countries with a press that is designated Free. The Freedom of the Press index assesses the degree of print, broadcast and internet freedom in every country, analyzing the events and developments of each calendar year. -

Ict Policy Review: National E-Commerce Strategy for Egypt United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT ICT POLICY REVIEW: NATIONAL E-COMMERCE STRATEGY FOR EGYPT UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT ICT POLICY REVIEW: NATIONAL E-COMMERCE STRATEGY FOR EGYPT New York and Geneva 2017 ii ICT POLICY REVIEW: NATIONAL E-COMMERCE STRATEGY FOR EGYPT © 2017, United Nations This work is available open access by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of any firm or licensed process does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. Photocopies and reproductions of excerpts are allowed with proper credits. This publication has been edited externally. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/DTL/STICT/2017/3 NOTE iii NOTE Within the Division on Technology and Logistics of UNCTAD, the ICT Policy Section carries out policy-oriented analytical work on the development implications of information and communications technologies (ICTs) and the digital economy, and is responsible for the biennial production of the Information Economy Report. The ICT Policy Section, among other things, promotes international dialogue on issues related to ICTs for development, such as e-commerce and entrepreneurship in the technology sector, and contributes to building developing countries’ capacities to design and implement relevant policies and programmes in these areas. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

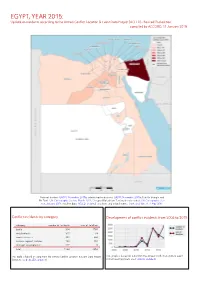

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

1 During the Opening Months of 2011, the World Witnessed a Series Of

FREEDOM HOUSE Freedom on the Net 2012 1 EGYPT 2011 2012 Partly Partly POPULATION: 82 million INTERNET FREEDOM STATUS Free Free INTERNET PENETRATION 2011: 36 percent Obstacles to Access (0-25) 12 14 WEB 2.0 APPLICATIONS BLOCKED: Yes NOTABLE POLITICAL CENSORSHIP: No Limits on Content (0-35) 14 12 BLOGGERS/ ICT USERS ARRESTED: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 28 33 PRESS FREEDOM STATUS: Partly Free Total (0-100) 54 59 * 0=most free, 100=least free NTRODUCTION I During the opening months of 2011, the world witnessed a series of demonstrations that soon toppled Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year presidency. The Egyptian revolution received widespread media coverage during the Arab Spring not only because of Egypt’s position as a main political hub in the Middle East and North Africa, but also because activists were using different forms of media to communicate the events of the movement to the world. While the Egyptian government employed numerous tactics to suppress the uprising’s roots online—including by shutting down internet connectivity, cutting off mobile communications, imprisoning dissenters, blocking media websites, confiscating newspapers, and disrupting satellite signals in a desperate measure to limit media coverage—online dissidents were able to evade government pressure and spread their cause through social- networking websites. This led many to label the Egyptian revolution the Facebook or Twitter Revolution. Since the introduction of the internet in 1993, the Egyptian government has invested in internet infrastructure as part of its strategy to boost the economy and create job opportunities. The Telecommunication Act was passed in 2003 to liberalize the private sector while keeping government supervision and control over information and communication technologies (ICTs) in place. -

Mr. Mahmoud Mohamed Ali 4 El Tayaran St., Nasr City, Cairo Tel: (20-2) 401-2692/21/22/23/24 Fax: (20-2) 401-6681

1 of 143 U.S. Department of State FY 2001 Country Commercial Guide: Egypt The Country Commercial Guide for Egypt was prepared by U.S. Embassy Cairo released by the Bureau of Economic and Business in July 2000 for Fiscal Year 2001. International Copyright, U.S. & Foreign Commercial Service and the U.S. Department of State, 2000. All rights reserved outside the United States. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 CHAPTER II. ECONOMIC TRENDS AND OUTLOOK 8 -Major Trends and Outlook -Principal Growth Sectors -Key Economic Trends and Issues -Economic Cooperation -Nature of Political Relationship with the U.S. -Major Political Issues Affecting Business Climate CHAPTER III. MARKETING U.S. PRODUCTS & SERVICES 17 -Distribution and Sales Channels -Use of Agents and Distributors - Finding a Partner -Franchising -Direct Marketing -Foreign Sales Corporation (FSC) -Joint Ventures/Licensing -Organization Structure and Management in Egypt -Steps to Establishing an Office -Selling Factors/Techniques -Advertising and Trade Promotion (and Selected Media List) -Pricing Products -Sales Service/Customer Support 2 of 143 -Selling to the Government -Tenders Law -Defense Trade -Protecting your Product from IPR Infringement (see Chapter VII) -Financing U.S. Agricultural Sales -Selling Through USAID Program CHAPTER IV. LEADING SECTORS FOR U.S. EXPORTS & INVESTMENT 41 -Best Prospects For Non-Agricultural Goods And Services -Best Prospects for Agricultural Products -Significant Investment Opportunities CHAPTER V. TRADE REGULATIONS, CUSTOMS, AND STANDARDS 55 -Trade Barriers (Including Tariff And Non-Tariff Barriers) and Tariff Rates -Import Taxes -Representative Listing of Commercial Legislation In Egypt -Customs Regulations -Import Licenses Requirements -Temporary Goods Entry Requirements -Special Import/Export Requirements And Certifications -Ministerial Decree 619 of 1998 - Certificate of Origin -Labeling Requirements -Prohibited Imports -Export Controls -Standards -Free Trade Zones/Warehouses -Membership in Free Trade Arrangements -Customs Contact Information CHAPTER VI. -

Palgrave Studies in Young People and Politics

Palgrave Studies in Young People and Politics Series Editors James Sloam Department of Politics and International Relations Royal Holloway, University of London Egham, UK Constance Flanagan School of Human Ecology University of Wisconsin–Madison Madison, WI, USA Bronwyn Hayward School of Social and Political Sciences University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand Over the past few decades, many democracies have experienced low or falling voter turnout and a sharp decline in the members of mainstream political parties. These trends are most striking amongst young people, who have become alienated from mainstream electoral politics in many countries across the world. Young people are today faced by a particu- larly tough environment. From worsening levels of child poverty, to large increases in youth unemployment, to cuts in youth services and educa- tion budgets, public policy responses to the fnancial crisis have placed a disproportionate burden on the young. This book series will provide an in-depth investigation of the changing nature of youth civic and political engagement. We particularly welcome contributions looking at: • Youth political participation: for example, voting, demonstrations, and consumer politics • The engagement of young people in civic and political institutions, such as political parties, NGOs and new social movements • The infuence of technology, the news media and social media on young people’s politics • How democratic innovations, such as social institutions, electoral reform, civic education, can rejuvenate democracy • The civic and political development of young people during their transition from childhood to adulthood (political socialisation) • Young people’s diverse civic and political identities, as defned by issues of gender, class and ethnicity • Key themes in public policy affecting younger citizens—e.g. -

Al-Ahram Weekly, 12-18 August 1999, Issue No. 442 Points of Reference, Ahmed Abdel-Moeti Hegazi I Knew Abdel-Wahab Al-Bayyati for More Than 40 Years

Al-Ahram Weekly, 12-18 August 1999, Issue No. 442 Points of reference, Ahmed Abdel-Moeti Hegazi I knew Abdel-Wahab Al-Bayyati for more than 40 years. And strangely, given the peripatetic nature of his life, we met for the first and last time in Cairo. I was 22 years old and he 31 when, in the winter of 1957, we met for the first time. The last time was earlier this year, when we both participated in a symposium held at the Cairo International Book Fair to celebrate 50 years since the emergence of free verse in Arabic. The last time I spoke to Al-Bayyati, though, was a few weeks ago, when I was in Paris, invited by the Institut du Monde Arabe to coordinate a festival of Arabic poetry scheduled for March next year. I suggested that a committee be formed bringing together people who might contribute to the success of such an event, and took it upon myself to contact Mahmoud Darwish, André Michael (the Arabic literature professor and head of the College de France), Gamaleddin Ben Sheikh and, of course, Al-Bayyati. We spoke over the telephone -- I in Paris, he in Damascus -- and he was full of energy as usual, and was as quick as ever to comment on the symposium in which we had both participated, and on the controversy that had ensued. Between our first and last meeting a great many miles have, of course, been covered. And for many of them we were fellow travellers, for I accompanied Al-Bayyati on many journeys, and visited him in many of the different places he would occupy -- the hotels and institutions, cafés and airports where he set up his temporary residence. -

April 2020 - ISSUE 37 INVEST-GATE

MARKET WATCH BY DINA EL BEHIRY POWERED BY POWERED BY MARKET WATCH REAL ESTATE INDUSTRY ACCOMPLISHMENTS NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR URBAN DEVELOPMENT 2052 REVENUE EXPECTATIONS IN 2020 TARGET New Urban Communities doubling urbanization rate Authority's (NUCA) target % % EGP bn HOUSING PROJECTS INFRASTRUCTURE Social Housing & Mortgage Finance Fund Offers New Units Government to Develop Roads Area Payment Period Up to 150 meters per unit Up to 20 years No. of Roads 197 Payment Method Minimum Installment Installments EGP 3,100 Roads’ Length 840 kilometers (km) Location Beit El Watan Project (7th Phase) Giza, Qaluobiya, Mounifya, Dakhlya, Beheira, Kafr El Sheikh, Sharqiyah, Gharbia, Damietta, Beni Suef, Fayoum & Minya New Housing Units Government to Construct New Roads Number of Cities Location 5 Sheikh Zayed, New Cairo, 6th of October, New Damietta & New Mansoura No. of Roads 2,652 New Residential Plots Roads’ Length 6,587 km Number of Cities Location 8 Sheikh Zayed, 6th of October, El Obour, New Damietta, Badr, New Cairo, El Shorouk Investments & Sadat EGP 12.7 bn Delivery Time Government to Implement New Projects in Fiscal Year (FY) 2019/20 2021-2022 Number of Projects Location Sohag, Beni Suef, Minya, 202 Assiut & Aswan Egyptian government to develop ring road Target Investments Developing villages EGP 944 mn with investments exceed EGP 7 bn Sources: Cabinet, Ministry of Housing, Ministry of Planning, Monitoring and Administrative Reform (MPMAR) & Social Housing and Mortgage Finance Fund. 2 aprIL 2020 - ISSUE 37 INVEST-GATE LAND OFFERING NUCA Offers Ministry of Housing Offers New Plots No. of New Plots Location Badr, Sadat, New Minya, 10th of Ramadan, 15th of May, 30 New Borg El Arab, New Beni Suef, New Assiut & New Aswan 25 5 Target New housing projects New Assiut East Port Said No. -

Dear Sir, I Am an Energetic, Experienced Academic

Dr-Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia Dear Sir, I am an energetic, experienced academic doctor aspiring to a challenging position as an Assistant Professor in (Civil Engineering-Structural) where I can apply my abilities and demonstrate my qualifications, motivation, enthusiasm and excellent communication skills. I have been teaching under-graduate students "Structure Analysis", "Characteristics and Test of Materials" and "Design of Reinforced Concrete Structures" courses in El-Shorouk Academy - Higher Institute of Engineering (Egypt), as well as supervision on graduation projects and teaching AutoCAD and SAP to graduated engineers in few training center in additional to teaching under-graduate students "Structure Analysis","Characteristics and Test of Materials" and "Inspection and non- destructive testing" and "Maintenance and Repairing of Structures" courses in El- Obour Higher Institute for Engineering and Technology (Egypt) and "Structure Analysis" and "Civil Engineering" at Faculty of Engineering, Misr International University (MIU). I have also more than ten years of working experiences in the field of structural designs, executive and workshop drawings. I think that my education, training and experiences make me a distinctive candidate for employment with your available position. Please, find my resume which represents my qualifications. Also, you may contact me for additional information. Thank You for Reading My C.V Best Regards, Dr. Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia Page 1 of 6 Dr-Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Data: Name: Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia. Date of birth: 11/1/1984. Nationality: Egyptian. Marital Status: Married. Military status: Permanent Exemption. Tel Mobile: +201000256520. Tel: +202/23828460. Address: 76 Ali Amein St, Nasr City, Cairo, Egypt.