Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man, Jacques Derrida and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN STILL ROOMS CONSTANTINE JONES the Operating System Print//Document

IN STILL ROOMS CONSTANTINE JONES the operating system print//document IN STILL ROOMS ISBN: 978-1-946031-86-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020933062 copyright © 2020 by Constantine Jones edited and designed by ELÆ [Lynne DeSilva-Johnson] is released under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non Commercial, No Derivatives) License: its reproduction is encouraged for those who otherwise could not aff ord its purchase in the case of academic, personal, and other creative usage from which no profi t will accrue. Complete rules and restrictions are available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ For additional questions regarding reproduction, quotation, or to request a pdf for review contact [email protected] Th is text was set in avenir, minion pro, europa, and OCR standard. Books from Th e Operating System are distributed to the trade via Ingram, with additional production by Spencer Printing, in Honesdale, PA, in the USA. the operating system www.theoperatingsystem.org [email protected] IN STILL ROOMS for my mother & her mother & all the saints Aιωνία η mνήμη — “Eternal be their memory” Greek Orthodox hymn for the dead I N S I D E Dramatis Personae 13 OVERTURE Chorus 14 ACT I Heirloom 17 Chorus 73 Kairos 75 ACT II Mnemosynon 83 Chorus 110 Nostos 113 CODA Memory Eternal 121 * Gratitude Pages 137 Q&A—A Close-Quarters Epic 143 Bio 148 D R A M A T I S P E R S O N A E CHORUS of Southern ghosts in the house ELENI WARREN 35. Mother of twins Effie & Jr.; younger twin sister of Evan Warren EVAN WARREN 35. -

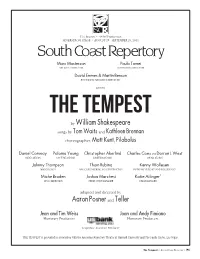

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

November 2016

The Bijou Film Board is a student-run UI org dedicated FilmScene Staff The to American independent, foreign and classic cinema. The Joe Tiefenthaler, Executive Director Bijou assists FilmScene with programming and operations. Andy Brodie, Program Director Andrew Sherburne, Associate Director PictureShow Free Mondays! UI students FREE at the late showing of new release films. Emily Salmonson, Dir. of Operations Family and Children’s Series Ross Meyer, Head Projectionist and Facilities Manager presented by AFTER HOURS A late-night OPEN SCREEN Aaron Holmgren, Shift Supervisor series of cult classics and fan Kate Markham, Operations Assistant favorites. Saturdays at 11pm. The winter return of our ongoing series of big-screen Dec. 4, 7pm // Free admission Dominick Schults, Projection and classics old and new—for movie lovers of all ages! Facilities Assistant FilmScene and the Bijou invite student Abby Thomas, Marketing Assistant Tickets FREE for kids, $5 for adults! Winter films play and community filmmakers to share Saturday at 10am and Thursday at 3:30pm. Wendy DeCora, Britt Fowler, Emma SAT, 11/5 SAT, their work on the big screen. Enter your submission now and get the details: Husar, Ben Johnson, Sara Lettieri, KUBO & THE TWO STRINGS www.icfilmscene.org/open-screen Carol McCarthy, Brad Pollpeter (2016) Dir. Travis Knight. A young THE NEON DEMON (2016) Spencer Williams, Theater Staff boy channels his parents powers. Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. An HORIZONS STAMP YOUR PASSPORT Nov. 26 & Dec. 1 aspiring LA model has her Cara Anthony, Felipe Disarz, for a five film cinematic world tour. One UI Tyler Hudson, Jack Tieszen, (1990) Dir. -

Film Studies (FILM) 1

Film Studies (FILM) 1 FILM 252 - History of Documentary Film (4 Hours) FILM STUDIES (FILM) This course critically explores the major aesthetic and intellectual movements and filmmakers in the non-fiction, documentary tradition. FILM 210 - Introduction to Film (4 Hours) The non-fiction classification is indeed a wide one—encompassing An introduction to the study of film that teaches the critical tools educational, experimental formalist filmmaking and the rhetorical necessary for the analysis and interpretation of the medium. Students documentary—but also a rich and unique one, pre-dating the commercial will learn to analyze cinematography, mise-en-scene, editing, sound, and narrative cinema by nearly a decade. In 1894 the Lumiere brothers narration while being exposed to the various perspectives of film criticism in France empowered their camera with a mission to observe and and theory. Through frequent sequence analyses from sample films and record reality, further developed by Robert Flaherty in the US and Dziga the application of different critical approaches, students will learn to Vertov in the USSR in the 1920s. Grounded in a tradition of realism as approach the film medium as an art. opposed to fantasy, the documentary film is endowed with the ability to FILM 215 - Australian Film (4 Hours) challenge and illuminate social issues while capturing real people, places A close study of Australian “New Wave” Cinema, considering a wide range and events. Screenings, lectures, assigned readings; paper required. of post-1970 feature films as cultural artifacts. Among the directors Recommendations: FILM 210, FILM 243, or FILM 253. studied are Bruce Beresford, Peter Weir, Simon Wincer, Gillian Armstrong, FILM 253 - History of American Independent Film (4 Hours) and Jane Campion. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Lundi 14 Novembre

ÉDITO Alain Rousset, Président du Festival 2015 et 2016 resteront deux années à part pour notre festival. En novembre dernier, suite aux attentats perpétrés avant la 26° édition, nous avons pris la décision de reporter notre manifestation. Ne pas céder sur nos principes : à savoir qu’un lieu de culture, de savoir et de dialogue comme le Festival ne saurait s’éteindre face à la peur. Ainsi, après « Un si Proche-Orient, » c’est le thème « Culture et liberté » qui s’impose comme une réponse fédératrice et constructive au climat anxiogène. Comme un lien emblématique entre les deux éditions de 2016, c’est Chahdortt Djavann, femme de conviction, écrivain française d’origine iranienne, qui nous parlera de culture au pluriel et de liberté à partir de son expérience singulière. Et nous sommes fiers de présenter le film posthume d’Andrezj Wajda qui dans « Afterimage » revient sur les persécutions subies par les artistes de l’autre côté du rideau de fer. De Khomeyni aux djihadistes, de Staline à Hitler, les régimes totalitaires n’ont eu de cesse d’anéantir la culture ou de l’instrumentaliser. Car l’expression artistique est une forme de liberté qui peut remettre en cause un pouvoir politique, religieux ou économique. Le premier enjeu de cette édition est de raconter et d’expliquer comment les artistes, les écrivains ont participé à l’Histoire. Comment, grâce à leur indépendance, à leur génie, ils ont pu éclairer, enchanter leur époque, briser les conformismes. Quelles ont été leurs géniales intuitions, leurs héroïques résistances ou leurs compromissions, leurs aveuglements. Le second enjeu est de montrer comment la culture peut rassembler, éveiller, émerveiller. -

October 29, 2013 (XXVII:10) Jim Jarmusch, DEAD MAN (1995, 121 Min)

October 29, 2013 (XXVII:10) Jim Jarmusch, DEAD MAN (1995, 121 min) Directed by Jim Jarmusch Original Music by Neil Young Cinematography by Robby Müller Johnny Depp...William Blake Gary Farmer...Nobody Crispin Glover...Train Fireman John Hurt...John Scholfield Robert Mitchum...John Dickinson Iggy Pop...Salvatore 'Sally' Jenko Gabriel Byrne...Charlie Dickinson Billy Bob Thornton...Big George Drakoulious Alfred Molina...Trading Post Missionary JIM JARMUSCH (Director) (b. James R. Jarmusch, January 22, 1981 Silence of the North, 1978 The Last Waltz, 1978 Coming 1953 in Akron, Ohio) directed 19 films, including 2013 Only Home, 1975 Shampoo, 1972 Memoirs of a Madam, 1970 The Lovers Left Alive, 2009 The Limits of Control, 2005 Broken Strawberry Statement, and 1967 Go!!! (TV Movie). He has also Flowers, 2003 Coffee and Cigarettes, 1999 Ghost Dog: The Way composed original music for 9 films and television shows: 2012 of the Samurai, 1997 Year of the Horse, 1995 Dead Man, 1991 “Interview” (TV Movie), 2011 Neil Young Journeys, 2008 Night on Earth, 1989 Mystery Train, 1986 Down by Law, 1984 CSNY/Déjà Vu, 2006 Neil Young: Heart of Gold, 2003 Stranger Than Paradise, and 1980 Permanent Vacation. He Greendale, 2003 Live at Vicar St., 1997 Year of the Horse, 1995 wrote the screenplays for all his feature films and also had acting Dead Man, and 1980 Where the Buffalo Roam. In addition to his roles in 10 films: 1996 Sling Blade, 1995 Blue in the Face, 1994 musical contributions, Young produced 7 films (some as Bernard Iron Horsemen, 1992 In the Soup, 1990 The Golden Boat, 1989 Shakey): 2011 Neil Young Journeys, 2006 Neil Young: Heart of Leningrad Cowboys Go America, 1988 Candy Mountain, 1987 Gold, 2003 Greendale, 2003 Live at Vicar St., 2000 Neil Young: Helsinki-Naples All Night Long, 1986 Straight to Hell, and 1984 Silver and Gold, 1997 Year of the Horse, and 1984 Solo Trans. -

Horaires Des Projections Screening Times

HORAIRES DES PROJECTIONS SCREENING TIMES LE POCKET GUIDE 2016 A ÉTÉ PUBLIÉ AVEC DES INFORMATIONS REÇUES JUSQU'AU 29/04/2016 THE POCKET GUIDE 2016 HAS BEEN EDITED WITH INFORMATION RECEIVED UP UNTIL 29/04/2016 Toutes les projections du Marché sont accessibles sur présentation du badge Marché du Film ou invitation délivrée par le Service Projections. Les projections dans les salles Lumière, Debussy, Buñuel, Salle du Soixantième, Théâtre Croisette et Miramar sont accessibles sur présentation du badge Marché ou Festival. Access to Marché du Film screenings is upon presentation of the Marché badge or an invitation given by the Marché Screening Department. Access to screenings taking place in Lumière, Debussy, Buñuel, Salle du Soixantième, Théâtre Croisette and Miramar is upon presentation of either a Marché or Festival badge. CO: Official Competition • HC: Out of Competition • CC: Cannes Classics • CR: Un Certain Regard • BLUE TITLE : Film screened for the first time at a market QR: Directors Fortnight • SC: Semaine de la critique • press: Press allowed • invite only: By invitation only • priority only: Priority badges only SUNDAY 15 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 08:30 (125’) CO 15:30 (158’) CO 19:30 (125’) CO 22:30 (116’) HC LUMIÈRE FROM THE LAND OF THE MOON AMERICAN HONEY FROM THE LAND OF THE MOON THE NICE GUYS TICKET REQUIRED Nicole Garcia Andrea Arnold Nicole Garcia Shane Black 2 294 seats STUDIOCANAL PROTAGONIST PICTURES STUDIOCANAL BLOOM 11:30 (145’) CO 14:30 (162’) CO 17:30 (120’) HC 19:45 (106’) HC SALLE AGASSI, THE -

Dead Man the Ultimate Viewing of William Blake

1 December 20, 2007 Terri C. Smith John Pruitt: Narrative film 311 Tangled jungles, blind paths, secret passage, lost cities invade our perception. The sites in films are not to be located or trusted. All is out of proportion. Scale inflates or deflates into uneasy dimensions. We wander between the towering and the bottomless. We are lost between the abyss within us and the boundless horizons outside us. Any film wraps us in uncertainty. The longer we look through a camera or watch a projected image the remoter the world becomes, yet we begin to understand that remoteness more. -- Robert Smithson from Cinematic Atopia1 Dead Man The Ultimate Viewing of William Blake When Jim Jarmusch incorporated his improvisational directorial approach, lean script- writing, minimalist aesthetic and passive characters into the seeming transcendental Western, Dead Man (1996), he subverted expectations of both his fans and detractors. The movie was polarizing for critics. During the time of its immediate reception, critics largely, seemed to either love it or hate it. Many people, especially non-European critics, saw Dead Man as explicitly ideological and full of itself. It was described as “a 1 Robert Smithson, “Cinematic Atopia” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. 141 1 2 misguided – albeit earnest undergraduate undertaking,”2 a “sadistic”3 127 minutes, “coy to a fault,”4 “punishingly slow,”5 and “shallow and trite.”6 Jarmusch is also attacked for being “hipper-than-thou”7 and smug. The juxtaposition of styles and genres bothered some. An otherwise positive review critiqued the “not-always-successful juxtapositions of humor and gore.” 8 For many it was Dead Man as a revisionist Western that became a problem. -

1 Ma, Mu and the Interstice: Meditative Form in the Cinema of Jim

1 Ma, Mu and the Interstice: Meditative Form in the Cinema of Jim Jarmusch Roy Daly, Independent Scholar Abstract: This article focuses on the centrality of the interstice to the underlying form of three of Jim Jarmusch’s films, namely, Stranger Than Paradise (1984), Dead Man (1995) and The Limits of Control (2009). It posits that the specificity of this form can be better understood by underlining its relation to aspects of Far Eastern form. The analysis focuses on the aforementioned films as they represent the most fully-fledged examples of this overriding aesthetic and its focus on interstitial space. The article asserts that a consistent aesthetic sensibility pervades the work of Jarmusch and that, by exploring the significance of the Japanese concepts of mu and ma, the atmospheric and formal qualities of this filmmaker’s work can be elucidated. Particular emphasis is paid to the specific articulation of time and space and it is argued that the films achieve a meditative form due to the manner in which they foreground the interstice, transience, temporality and subjectivity. The cinema of Jim Jarmusch is distinctive for its focus on the banal and commonplace, as well as its rejection of narrative causality and dramatic arcs in favour of stories that are slight and elliptical. Night on Earth (1991), a collection of five vignettes that occur simultaneously in separate taxis in five different cities, explores the interaction between people within the confined space of a taxi cab and the narrow time-frame necessitated by such an encounter, while Coffee and Cigarettes (2004) focuses on similarly themed conversations that take place mostly in small cafes.1 The idea of restricting a film to such simple undertakings is indicative of Jarmusch’s commitment to exploring underdeveloped moments of narrative representation. -

Dead Man, Legal Pluralism and the De-Territorialization of the West

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Articles & Book Chapters Faculty Scholarship 2011 "Passing Through the Mirror": Dead Man, Legal Pluralism and the De-Territorialization of the West Ruth Buchanan Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Source Publication: Law, Culture and the Humanities. Volume 7, Number 2 (2011), p. 289-309. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Buchanan, Ruth. ""Passing Through the Mirror": Dead Man, Legal Pluralism and the De-Territorialization of the West." Law, Culture and the Humanities 7.2 (2011): 289-309. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. ‘‘Passing through the Mirror’’: Dead Man, Legal Pluralism and the De-territorialization of the West Ruth M. Buchanan Osgoode Hall Law School,York University Abstract The failures of Western law in its encounter with indigenous legal orders have been well documented, but alternative modes of negotiating the encounter remain under-explored in legal scholarship. The present article addresses this lacuna. It proceeds from the premise that the journey towards a different conceptualization of law might be fruitfully re-routed through the affect-laden realm of embodied experience – the experience of watching the subversive anti- western film Dead Man. Section II explains and develops a Deleuzian approach to law and film which involves thinking about film as ‘‘event.’’ Section III considers Dead Man’s relation to the western genre and its implications for how we think about law’s founding on the frontier. -

American Independent Film Dead Man Production Timeline

English 345: American Independent Film Dead Man Production Timeline Jim Jarmusch on independent film in the mid-1990s: “The whole idea of independent is very perplexing to me. I don't know what it means anymore. It used to be that small films could be made without a lot of money and therefore without as much interference from people who were interested solely in making money off the movie. There's a place for business in cinema. It is, to a large degree, business. Smaller films—which used to be called independent—used to be a place for people to express their ideas, and a lot of the strongest or newest ideas came from them. But, recently, I don't quite understand what it means anymore, because a lot of „independent‟ producers are interested in making a name for themselves—to get money to launch their careers. So, I see people making films for $500,000 with producers and people telling them to change the script, whom to cast and how to cut it and I don't understand what independent is any more. People who are called independent make films for large studios. Miramax—owned by Disney—which is going to release this film in North America is called an independent distribution company or production company. Consequently, I don't know what that word means any more.” “A Neo-Western on Life and Death.” Film International 3:4 (Autumn 1995). Reprinted in The Jim Jarmusch Resource Page. Production Timeline 1990: Jarmusch begins collaborating with novelist and screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer on Western titled Ghost Dog.