Supporting Social, Emotional, & Academic Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objection To, Or Fault Found with Applicant’S Services Marketed Under

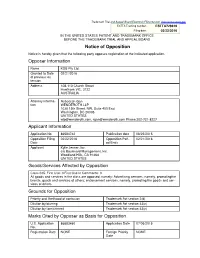

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA728619 Filing date: 02/22/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name KDB Pty Ltd. Granted to Date 02/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address 108-110 Church Street Hawthorn VIC, 3122 AUSTRALIA Attorney informa- Rebeccah Gan tion WENDEROTH LLP 1030 15th Street, NW, Suite 400 East Washington, DC 20005 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected] Phone:202-721-8227 Applicant Information Application No 86584742 Publication date 08/25/2015 Opposition Filing 02/22/2016 Opposition Peri- 02/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Kylie Jenner, Inc. c/o Boulevard Management, Inc. Woodland Hills, CA 91364 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 035. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Advertising services, namely, promotingthe brands, goods and services of others; endorsement services, namely, promoting the goods and ser- vices of others Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Dilution by blurring Trademark Act section 43(c) Dilution by tarnishment Trademark Act section 43(c) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application 86683460 Application Date 07/06/2015 No. Registration Date NONE Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark KYLIE MINOGUE DARLING Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 003. -

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle by Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle Supervising Committee Zoe Detsi, supervisor _____________ Christina Dokou, co-adviser _____________ Konstantinos Blatanis, co-adviser _____________ This doctoral dissertation has been conducted on a SSF (IKY) scholarship via the “Postgraduate Studies Funding Program” Act which draws from the EP “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning” 2014-2020, co-financed by European Social Fund (ESF) and the Greek State. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki I dress to kill, but tastefully. —Freddie Mercury Table of Contents Acknowledgements...................................................................................i Introduction..............................................................................................1 The Camp of Diva: Theory and Praxis.............................................6 Queer Audiences: Global Gay Culture, the Arena Tour Spectacle, and Fandom....................................................................................24 Methodology and Chapters............................................................38 Chapter 1 Times -

Edición Impresa

Deportes Páginas 12 a 15 VICKY,VETADA EUROCOPA ALEJANDRO Los rivales de BLANCO POR CHICA España también El presidente del Timonel todo el año,ahora no la han flojeado en COE estuvo ayer dejan competir con hombres en los Nacionales. sus amistosos en 20minutos.es La crisis dispara en la región las compras El primer diario que no se vende con tarjeta de crédito Martes 3 JUNIO DE 2008. AÑO IX. NÚMERO 1943 En 2007 sumaron 10.000 millones de euros, y este año van camino de 12.000 milones. Elnúmerode‘plásticos’expedidos ha crecido un 15% en un año. Muchasfamilias Sólo un ex concejal de Madrid es condenado por el ‘caso Funeraria’ ya pagan a crédito no sólo bienes duraderos, sino incluso la cesta de la compra. 2 Es Luis María Huete. El resto de implicados, entre ellos otros dos ex ediles, han sido absueltos. 3 Más de 5.000 universitarios logran becas Larevista de la Comunidad por su rendimiento En las categorías Excelencia, Erasmus y Disca- pacidad. Los primeros, 4.500 euros cada uno. 4 Multa de 60.000 euros al Sermas por un bebé que contrajo hepatitis C en La Paz El contagio se produjo en 1990, porque el centro no aplicó los marcadores que detectan el virus. 3 ! O L A S Á P Las matriculaciones de coches cayeron un 24% en mayo respecto al pasado año Las ventas de turismos han bajado una media de un 14,3% en los primeros cinco meses de 2008. 6 HOUSE SE DESPIDE ENFERMO La popular serie de televisión llega esta noche al final de su cuarta temporada,mu- Costa dice que al PP le cho más corta de lo previsto.Y el doctor House es,además de médico,paciente. -

DE EQUITIBUS INSIDE Robotics Middle School Baseball Team Team Concludes Successful Season

Vol. X No. 6 - Wed., March 4, 2020 DE EQUITIBUS INSIDE Robotics Middle school baseball team team concludes successful season. scores big Page 6 at ASU event. Page 3 Teen Court members help offenders get, stay on right path By Taylor Conley Knock! Knock! It’s gavel-time! Some TPA students choose to spend their pre- cious time attending Guadalupe Teen Court every Wednesday after school. Unlike other teen courts, GTC is not as- sociated with any particular school and welcomes students from all over the area. Guadalupe Teen Court consists of case- days and non-case-days. On a day without hearings, we may meet lawyers or judges. On one occasion, Dani Delgado, TPA’s speech and debate coach, led a presenta- tion on the USA’s foreign affairs, particu- larly about US-Iran tensions. Presentations Guadalupe Teen Court members prepare to hear cases. like these help crystallize events like these for people who do not understand. Throughout high school, Dani was part of we must consider different mitigators and on the project. In fact, teen offenders are GTC herself, and now helps as an alumna instigators, such as their family dynamics drastically less likely to commit another leader. In addition, GTC has visited other or school life. crime after attending Teen Court. courts and has even gone to Washington After listening to the defendant give Michelle Hirsch took over GTC when DC. their side of the story and asking ques- Judge Alvarez chose to move higher up Violeta Panayotova, a junior and avid tions about them, the jury discusses the the circuit. -

01 Cover JULY.Indd

B63C:B7;/B35C723B=5/G:=<2=< 4@33 9G:73E=EE=EE=E 7<A723¬D/<1=CD3@>@723:=<2=</<<735/G07<5= EEE=Cb;/51=C9 7AAC3<7<3B33<%& =C :=@3; bZ]`S[ WORDS BY LOREM DELOREM | PHOTOGRAPH BY MAET IPSUM =CbT`]\b Knight Hooson has an EDITORIAL// immigrant’s view of ADVERTISING the British PAGE 46 Editor INTERNATIONAL MR David Hudson LEATHER [email protected] Chris Jepson reports +44 (0)20 7258 1943 from the annual Contributing Editor International Mr Adrian Gillan Leather contest in [email protected] Chicago Design Concept Splicer Design PAGE 51 www.splicerdesign.com OUT THERE Art Director Upcoming scene Markus Scheef highlights for July, plus [email protected] PAGE 20 coverage of Hustlaball, Designer KYLIE XXL Bear Pride and Siv Nilsen Circus Sub Editor Kathryn Fox PAGE 81 Contributors OUTREACH Marc Andrews, Dan Browne, Dr Justin Varney on Paul Burston, Charlotte making your protests Dingle, Adrian Foster, Knight CONTENTS heard Hooson, Cary James, Gary Ryan, Richard Tonks, Michael Turnbull, Justin Varney, Iwan PAGE 04 Watson, Steve Watson LETTERS Photographers Send your Chris Jepson, Dick Goose correspondence to Publisher [email protected] Sarah Garrett//Linda Riley ISDN: 1473-6039 HUDSON’S LETTER PAGE 06 Head of Business Development Walking on the Pride I think I’ve been on every MY LONDON Rob Harkavy London parade last Pride march in London Gaydar radio and [email protected] year, I was struck by the since 1989, and the Classic FM’s Jamie Crick PAGE 54 +44 (0)20 7258 1936 huge number of gay faces numbers taking part on BEAR PRIDE Sales Executive I recognised lining the the parade have dwindled PAGE 08 Dan Goodban route… compared to the over the years. -

Shows Fit for a King's Castle!

™ — P 3 OUR ALMOST SHOWS FIT FOR A TELL-ALL INTERVIEW: RHONDA VINCENT’S KING’S CASTLE! CHRISTMAS IN BRANSON! ■ HER SHOW ■ HER GUEST STARS & WHAT SHE WON’T TELL US! GLOBAL SENSATIONS DAZZLE BRANSON! INSIDE: (& BLOW UP TRIP ADVISOR!) ■ VETERANS HOMECOMING! ■ HUGE HUGHES NEWS! ALSO APPEARING AT — P 11 PLUS KING’S CASTLE— ■ THE NEW SHOW MADE FOR TV! — P 9 SHOW SCHEDULE • MAP • FOOD • SHOPPING • FUN! ADVENTURES WITH YAKOV! marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War, and ultimately of the Soviet Union’s socialist empire. For Yakov, it was the role of a lifetime. He grew up in Joseph Stalin’s USSR, his family sharing a small apartment with eight other families. Somehow, he was able to find joy in making others laugh. After two years of required service in the Soviet Army, he landed a comedy job on a cruise ship, yet always under the watchful eye of the KGB and Soviet authorities who carefully reviewed all his material. e’s back, giving us a golden After two years of paperwork, Yakov and his opportunity to experience one of the family were finally allowed to emigrate to most amazing entertainers of all time! America. They arrived in New York with less than a hundred dollars in their pockets. HIt’s a short window— but it’s an opportunity that would be wise to seize, for it’s rare to As always, Yakov’s comedy draws from the witness a performer whose influence actually news and from life—ours as well as his. But played a role in changing our world! that’s not all. -

El Videoclip Como Paradigma De La Música Contemporánea, De 1970 a 2015

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y PUBLICIDAD I TESIS DOCTORAL El videoclip como paradigma de la música contemporánea, de 1970 a 2015 MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTORA PRESENTADA POR Lara García Soto DIRECTOR Francisco Reyes Sánchez Madrid, 2017 © Lara García Soto, 2016 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de CC. de la Información Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad I El videoclip como paradigma de la música contemporánea, de 1970 a 2015 Tesis doctoral presentada por: Lara García Soto. Tesis doctoral dirigida por: Francisco Reyes Sánchez. Madrid, 2015 El ejemplo, la fuerza y el esfuerzo, mis padres. La paciencia y apoyo, Adrián. La música, baile y mi inspiración, Michael Jackson. Gracias. ÍNDICE 1. Introducción y Objeto de estudio……………………………………1 2. Objetivos……………………………………………………………….6 3. Metodología………………………………………............................10 4. Orígenes……………………………………………………………….13 4.1. Cine sonoro y experiencias artísticas………………………13 4.2. Cine Musical…………………………………………………..18 4.3. Soundies y Scopitones……………………………………….25 4.4. La llegada de las películas rock, grabaciones de conciertos. Décadas de los 50 y 60……………………………………………29 4.5. El videoarte……………………………….............................38 4.6. La televisión y los programas musicales………………......41 4.6.1. La MTV………………………………………………...........48 4.6.2. Programas musicales en España………………………...57 4.6.3. Los canales temáticos de música y videoclips………….65 5. Historia de la música y relación con los videoclips……………….68 5.1. Los años 70…………………………………………………..69 5.2. Los años 80…………………………………………………..76 5.2.1. La televisión y los videoclips. Desarrollo del rap…..80 5.2.2. El primer muro. El PMRC…………………………….86 5.2.3. Continúa la evolución: música, tecnología y moda..89 5.2.4. -

On STAGE WA MARITIME MUSEUM FREMANTLE 16.02.2019—09.06.2019 CONTENTS

LEARNING RESOURCE KIT WA MARITIME MUSEUM presents A TOURING EXHIBITION BY ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE AND THE AUSTRALIAN MUSIC VAULT on STAGE WA MARITIME MUSEUM FREMANTLE 16.02.2019—09.06.2019 CONTENTS: Welcome How to use this Resource Section 1 - What is an Exhibition? 1.1. Activity Introduction 1.2. Prezi – What is an Exhibition? 1.3. Types of Exhibition Spaces 1.4. The ACM Collection 1.5. Acquiring Artefacts and Artworks 1.6. Conservation of Artworks and Artefacts 1.7. ACM on Display 1.8. Activity – Who works in the team? 1.9. The Collections Team 1.10. Activity – The Exhibition of Me Section 2 – All Things Kylie 2.1. Introduction 2.2. Prezi – Kylie Career Overview 2.3. Video – Kylie – the curator’s insight 2.4. Activity – Visiting the Kylie on Stage Exhibition live or online Section 3 – Designing an Icon 3.1. What makes an Icon? 3.2. Interpreting a Song 3.3. Activity – Interpreting a Song 3.4. Garment Design Elements and Principles 3.5. Activity – Design Elements and Principles 3.6. Activity – Design Analysis Activity 3.7. Activity – Mood Board Activity 3.8. Activity – Designing a Costume 3.9. Activity – Making a Costume Appendix A – Offer of Donation Form Appendix B – Condition Report - Kylie Costume Appendix C – ACM Exhibitions Appendix D – Catalogue Worksheet Appendix E – Condition Report – Blank Appendix F – Elements and Principles Template Novice Appendix G – Elements and Principles Template Advanced Appendix H – Croquis Templates Curriculum Links Credits WELCOME Thank-you for downloading the Kylie on Stage Learning Resources. We hope you and your students enjoy learning about collections, exhibitions, music and costumes and of course Kylie Minogue as much as us! Kylie on Stage is a major free exhibition celebrating magical moments from Kylie’s highly successful concert tours around Australia. -

Murray-Darling Basin Annual Report 2014-15

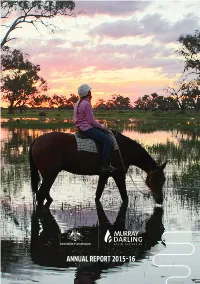

ANNUAL REPORT 2015–16 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF THE TRADITIONAL OWNERS OF THE MURRAY–DARLING BASIN The Murray–Darling Basin Authority acknowledges and 'The environment that pays respect to the Traditional Aboriginal people know Owners, and their Nations, as Country has not been of the Murray–Darling Basin, allowed to have a voice in who have a deep cultural, contemporary Australia. social, environmental, spiritual Aboriginal First Nations have and economic connection to been listening to Country for their lands and waters. The many thousands of years MDBA understands the need and can speak for Country so for recognition of Traditional that others can know what Owner knowledge and cultural values in natural resource Country needs. Through the management associated with the basin. Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations and the The approach of Traditional Owners to caring for the Northern Basin Aboriginal natural landscape, including water, can be expressed in Nations the voice of Country the words of Darren Perry (Chair of the Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations) can be heard by all.' BARAPA BARAPA BARKINDJI (PAAKANTYI) NARI NARI NGARRINDJERI BARUNGGAM BIDJARA NGEMBA NGINTAIT BIGAMBUL BUDJITI NGIYAMPAA NYERI NYERI DHUDHUROA DJA DJA WURRUNG TATTI TATTI TAUNGURUNG EUAHLAYI GAMILAROI WADI WADI WAILWAN GITHABUL GUNGGARI WAMBA WAMBA WAKKA WAKKA GWAMU (KOOMA) JAROWAIR WAYWURRU WEGI WEGI KAMBUWAL KUNJA WERGAIA WIRADJURI KWIAMBUL LATJI LATJI WOLGALU WOTJABALUK MALJANGAPA MANDANDANJI YAITMATHANG YITA YITA MARAURA MARDIGAN YORTA YORTA MURRAWARRI MUTTI MUTTI This report may contain photographs or quotes by Aboriginal people who have passed away. Most Aboriginal words can be spelt more than one way in English so spellings may vary in this publication. -

City Approves of Darling's Plan to Buy Sanibel Kicks Back Elections

SDFf 77' ^, , SAN t a, ( and 339-7 PORT 'eekof Feb. 21-27,2002 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 29, NUMBER 8, 32 PAGES 75 CENTS 3sy Ops' City approves of Darling's plan to buy sychological warfare e war of terrorism. By Erik Burriss ernments are looking for Sambel developed. to it based the possible effect of Staff writer to take the lead in supporting the "We're conservationists, and the refuge's expansion on boaters. —See page 3 proposal. we're trying to preserve what you Any effect should be minimal, Saying that protecting the off- "If you don't have the home- want to preserve," he said. "It's us Jess said, since all open waters schy solution island environment is necessary town, what do you have? It's very or the developers." and channels would be excluded for the protection of Sanibel's important to me to have the city of If approved, Jess said the U.S. from the expansion, except for tie Sambel Police environment, City Council ap- Sanibel's support." Fish and Wildlife Service could possible 100-meter buffers around ok to technology for proved a resolution Tuesday sup- The Lee County Board of Com- enter into management agree- six islands to protect threatened high-tech solution. porting a plan that would allow the missioners postponed making a ments with property owners or bird species' nesting sites. J.N. "Ding" Darling National decision on a similar resolution lease or buy or obtain conserva- The proposed buffers would —See page 3 Wildlife Refuge Complex to look Feb. -

By: Kylie Worrell

By: Kylie Worrell This October is something else, which doesn’t seem too out of place given what’s happened in 2020 so far… but there are a couple things that are a bit unsettling and alarming, possibly, headed our way. Firstly, did you guys know there is another outbreak in China? According to CNN and other television broadcasting systems, there is an outbreak of a bacterial infection called “ Brucellosis”, after a leak in a biopharmaceutical factory back in 2019. This infection has affected thou- sands now, as it is livestock that normally carries Brucella, which means it could possibly be in the meat that is packaged and shipped over to the U.S.. Most say it is very much similar, if not the same as Mediterranean fever, which can cause fatigue, muscle pain, nausea, headaches and high fevers and sometimes these symp- toms never subside, they can swell the organs and it can lead to many complications including death. Human to human transmission is rare, but be careful around livestock and the meat you eat. https://www.health.com/condition/infectious-diseases/brucellosis-outbreak-china?amp=true https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/2020/09/17/asia/china-brucellosis-outbreak-intl-hnk/index.html Next, do not panic! As we all know, election day is November 3rd, 2020. Ironically, there is an asteroid on course to collision, if not very close to collision, with us. As of now, NASA has not said much besides on twitter and local news sta- tions. National news stations have gotten word of this and have exploited it. -

STAR V86,7 October-7-1993.Pdf (11.69Mb)

rfOpoiLy Ot Willard J. Houghton Librari Houghton, New York 14744 Volume 86.7 THE HOUGHTON October 7, 1993 WORLD AT A GLANCE Rain on the Homecoming Wm. Mann Parade doesn't dampen spirits India - The largest earthquake to hit India in the last 50 years Angela Fulkroad took place in the Wesley pompons and were costumed as Chinese rickshaw, Canadian is estimated to leave as many as Homecoming weekend at Chapel ai 11:30 a.m., follow- athletes. The Third place backpackers, a Mexican F 30,000 people dead and many Houghton would not be ing the parade. winners were the sophomores. motorcycle gang, and Isnelian more maimed and injured. The complete without the tradi- Each class braved the rain The sophomores worked with camel and Arabian terrorists quake, registering 6.4, struck tional parade of class floats and to present their class floats and the theme "Jazz up Your Life who were defeated by Austrian southeast of Bombay in the the coronation of the Home- spirit to alumni, faculty, with Art" and entitled their float musclemen "Hans" and / region of Kill:ri. coming King and Queen. On family, friends, and fellow 'living Art" The float "Frans." The junior class of Rusfia - Soviet hard-liners Saturday, October 2nd, at 10 students. The floats correlated consisted of mimes and a skit 1995 won the First place uophy continue to hold up inside a.m., members of the freshmen, to this year's Homecoming about an artist frustrated when with their float entitled "Jazz 1 parliament two weeks now sophomore. junior, and senior Jazz theme.