Introducing the Incomparable Hildegarde: the Sexuality, Style, and Image of a Forgotten Cultural Icon Monica Gallamore Marquette University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Us Constitution As Icon

EPSTEIN FINAL2.3.2016 (DO NOT DELETE) 2/3/2016 12:04 PM THE U.S. CONSTITUTION AS ICON: RE-IMAGINING THE SACRED SECULAR IN THE AGE OF USER-CONTROLLED MEDIA Michael M. Epstein* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….. 1 II. CULTURAL ICONS AND THE SACRED SECULAR…………………..... 3 III. THE CAREFULLY ENHANCED CONSTITUTION ON BROADCAST TELEVISION………………………………………………………… 7 IV. THE ICON ON THE INTERNET: UNFILTERED AND RE-IMAGINED….. 14 V. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………….... 25 I. INTRODUCTION Bugs Bunny pretends to be a professor in a vaudeville routine that sings the praises of the United States Constitution.1 Star Trek’s Captain Kirk recites the American Constitution’s Preamble to an assembly of primitive “Yankees” on a far-away planet.2 A groovy Schoolhouse Rock song joyfully tells a story about how the Constitution helped a “brand-new” nation.3 In the * Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School. J.D. Columbia; Ph.D. Michigan (American Culture). Supervising Editor, Journal of International Media and Entertainment Law, and Director, Amicus Project at Southwestern Law School. My thanks to my colleague Michael Frost for reviewing some of this material in progress; and to my past and current student researchers, Melissa Swayze, Nazgole Hashemi, and Melissa Agnetti. 1. Looney Tunes: The U.S. Constitution P.S.A. (Warner Bros. Inc. 1986), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5zumFJx950. 2. Star Trek: The Omega Glory (NBC television broadcast Mar. 1, 1968), http://bewiseandknow.com/star-trek-the-omega-glory. 3. Schoolhouse Rock!: The Preamble (ABC television broadcast Nov. 1, 1975), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHp7sMqPL0g. 1 EPSTEIN FINAL2.3.2016 (DO NOT DELETE) 2/3/2016 12:04 PM 2 SOUTHWESTERN LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Betting the Farm: the First Foreclosure Crisis

AUTUMN 2014 CT73SA CT73 c^= Lust Ekv/lll Lost Photographs _^^_^^ Betting the Farm: The First Foreclosure Crisis BOOK EXCERPr Experience it for yourself: gettoknowwisconsin.org ^M^^ Wisconsin Historic Sites and Museums Old World Wisconsin—Eagle Black Point Estate—Lake Geneva Circus World—Baraboo Pendarvis—Mineral Point Wade House—Greenbush !Stonefield— Cassville Wm Villa Louis—Prairie du Chien H. H. Bennett Studio—Wisconsin Dells WISCONSIN Madeline Island Museum—La Pointe First Capitol—Belmont HISTORICAL Wisconsin Historical Museum—Madison Reed School—Neillsville SOCIETY Remember —Society members receive discounted admission. WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Director, Wisconsin Historical Society Press Kathryn L. Borkowski Editor Jane M. de Broux Managing Editor Diane T. Drexler Research and Editorial Assistants Colleen Harryman, John Nondorf, Andrew White, John Zimm Design Barry Roal Carlsen, University Marketing THE WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY (ISSN 0043-6534), published quarterly, is a benefit of membership in the Wisconsin Historical Society. Full membership levels start at $45 for individuals and $65 for 2 Free Love in Victorian Wisconsin institutions. To join or for more information, visit our website at The Radical Life of Juliet Severance wisconsinhistory.org/membership or contact the Membership Office at 888-748-7479 or e-mail [email protected]. by Erikajanik The Wisconsin Magazine of History has been published quarterly since 1917 by the Wisconsin Historical Society. Copyright© 2014 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. 16 "Give 'em Hell, Dan!" ISSN 0043-6534 (print) How Daniel Webster Hoan Changed ISSN 1943-7366 (online) Wisconsin Politics For permission to reuse text from the Wisconsin Magazine of by Michael E. -

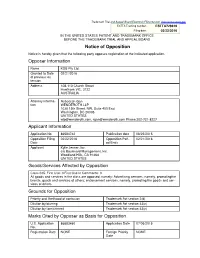

Objection To, Or Fault Found with Applicant’S Services Marketed Under

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA728619 Filing date: 02/22/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name KDB Pty Ltd. Granted to Date 02/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address 108-110 Church Street Hawthorn VIC, 3122 AUSTRALIA Attorney informa- Rebeccah Gan tion WENDEROTH LLP 1030 15th Street, NW, Suite 400 East Washington, DC 20005 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected] Phone:202-721-8227 Applicant Information Application No 86584742 Publication date 08/25/2015 Opposition Filing 02/22/2016 Opposition Peri- 02/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Kylie Jenner, Inc. c/o Boulevard Management, Inc. Woodland Hills, CA 91364 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 035. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Advertising services, namely, promotingthe brands, goods and services of others; endorsement services, namely, promoting the goods and ser- vices of others Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Dilution by blurring Trademark Act section 43(c) Dilution by tarnishment Trademark Act section 43(c) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application 86683460 Application Date 07/06/2015 No. Registration Date NONE Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark KYLIE MINOGUE DARLING Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 003. -

P Assion Distribution a Utumn 2020 • New Programming

AUTUMN 2020 • AUTUMN NEW PROGRAMMING PASSION DISTRIBUTION PASSION PART OF THE TINOPOLIS GROUP Passion Distribution Ltd. No.1 Smiths Square 77-85 Fulham Palace Road London W6 8JA T. +44 (0)207 981 9801 E. [email protected] www.passiondistribution.com WELCOME I’m delighted to welcome you to the second edition of our pop-up market and share with you our latest catalogue this autumn. Although it has been a challenging time for everyone, we have worked tirelessly to bring together a slate of quality programming for your schedules. Extraordinary human stories, iconic historical moments, premium documentaries and essential entertainment remain some of our key priorities. Our slate doesn’t disappoint in delivering new programmes of immense quality. Perhaps a sign of the times, our line-up includes a strong offering of history programming. The new landmark series 1000 Years brings together some of the most talented UK producers to chart the extraordinary rise of six countries that have profoundly shaped our world. WELCOME We also take a closer look at the Nuremberg trials – one of the 21st century’s defining events – by casting new light on the “trial of the century” in time for the 75th anniversary in November. On a lighter note in our factual entertainment section some other key franchises return with new episodes. Emma Willis has welcomed new babies in lockdown, Traffic Cops have remained on patrol, and we continue to see dramatic stories unfold in the access-driven Inside the Police Force. As you’d expect, a new series of the US hit-show RuPaul’s Drag Race has been announced – this incredible global phenomenon is now in its 13th season. -

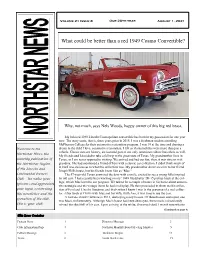

What Could Be Better Than a Red 1949 Cosmo Convertible?

Volume 21 Issue 8 Our 20th year August 1, 2021 What could be better than a red 1949 Cosmo Convertible? Why, not much, says Nels Woods, happy owner of this big red beast. My beloved 1949 Lincoln Cosmopolitan convertible has been in my possession for one year now. The story starts, that is, three years prior in 2018. I was a freshman student attending McPherson College for their automotive restoration program. I was 19 at the time and chasing a Welcome to the dream in the field I love, automotive restoration. I felt as if automobiles were more than just a vehicle. Classic cars are history, an essential part of not only American culture but others as well. Northstar News, the My friends and I decided to take a fall trip to the great state of Texas. My grandmother lives in monthly publication of Texas, so I am never opposed to visiting. We arrived and had our fun; then, it was time to visit the Northstar Region grandma. She had mentioned a friend of hers with a classic car collection. I didn't think much of it, but I was curious as to what this collection was. My grandmother drove me over to her friend of the Lincoln and Joseph Hill's house, but his friends knew him as "Mac." Continental Owners The 87-year-old Texan answered the door with a smile, excited to see a young fella inspired Club. We value your by old cars. I had recently been working on my ‘1949 Studebaker 2R-15 pickup truck at the col- lege, which Mac loved to see progress. -

Hoan, Daniel Webster Papers Call Number

Title: Hoan, Daniel Webster Papers Call Number: Mss-0546 Inclusive Dates: 1889 – 1966 Bulk: 59.6 cubic feet total Location: EW, Sh. 001-018 (38 cu. ft.) EW, Sh. 027 (1.4 cu. ft.) ER, Sh. 206-209 (15.8 cu. ft.) ER, Sh. 210 (4.4 cu. ft.) OS XLG (1 item) OS LG “H” (3 items) OS SM “H” (12 items) Abstract: Daniel Webster Hoan served as Mayor of Milwaukee form 1916 to 1940. He was born on March 31, 1881 in Waukesha, Wisconsin. He left school in the sixth grade but worked as a cook to finance his education at the University of Wisconsin, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1905. Hoan moved to Chicago after his graduation and attended Kent College, earning his Law degree in 1908. In 1909 he married his first wife, Agnes Bernice Magner. They had two children, Daniel Webster Jr. and Agnes. In 1944, after his first wife’s death, he married Gladys Arthur Townsend. Hoan was recruited by local Socialists to Milwaukee in 1908. Working as a labor lawyer he drafted the nation’s first workmen’s compensation law in 1911. Hoan became city attorney in 1910, and he was reelected in 1914. In 1916, Hoan beat incumbent Mayor Gerhard A. Bading. Daniel Hoan was reelected six times, until in 1940 he was defeated by Carl F. Zeidler. Hoan emphasized his Socialist party alliance, but he was more interested in improving services and government, so-called “sewer socialism”, than political theory. Hoan forged an enviable record, eliminating graft, improving the city’s health and safety, supporting harbor improvement and reducing debt. -

Ice Cream Airport and Landing Areas, Carry by Popular Demand We Are Continulbg Tus Special Another Week Dropped Today, Helping Weary Fire Life

FRIDAY, AUGtrST 11, 1961 Averaffe Net Press Run The Weather For tho Weak Ended ForecMt of O. 8. Weather gone 8, 1981 ^ The weekly Friday dances sponsored by the recreation de Tot’s First Drive itsm , ___ ___ _ « I 13,3.30 Clearing, cooler,tonight. Low In About Town partment win be held tonight at Sartor to Train at Chanute mld-60e, Suqday moetly. mmny, the West Side tennis courts from Ends with Crash Member of the Audit cooler, letM humid. High 88 to 86. Mancheider Banmcki, Vateraas 7:30 to 8:30 for youngsters As CAP Cadet^ Then Airman Boreau of Gircalatlon Of WorW War I, will be hoet to a throught 12. and 8:30 to 10:30 Manchester— A City of Village Charm for teen-agers. A three-year-old’s first experi department meeting of the De ence with driving had crashing re partment of Connecticut Sunday Cadet Capt. Richard Sartor of >year the space program has been liiii mghth District Fire Department sults last night The lad only re VOL. LXXX, NO. 266 (TEN PAGES—TV SECHON—SUBURBIA TODAY) lilANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, AUGUST 12, 1961 (Clooaifled Advertteiog on Page 8) PRICE FIVE CENTS at S p.m. at the VPW Poat Home, the Manchester Cadet Squadron of offered. MANCHESTER iilil members who wish to participate Sartor has passed tests on mis-. ceived a bump on the forehead. MAIN STREET Manclieater Green. Barracks and the a v ll Air Patrol will receive auxiliary units throughout the In a parade in Broad Brook will sUes and rocketry conducted by training at the same U.S. -

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) Was An

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Born to a wealthy family in Indiana, he defied the wishes of his dom ineering grandfather and took up music as a profession. Classically trained, he was drawn towards musical theatre. After a slow start, he began to achieve succe ss in the 1920s, and by the 1930s he was one of the major songwriters for the Br oadway musical stage. Unlike many successful Broadway composers, Porter wrote th e lyrics as well as the music for his songs. After a serious horseback riding accident in 1937, Porter was left disabled and in constant pain, but he continued to work. His shows of the early 1940s did not contain the lasting hits of his best work of the 1920s and 30s, but in 1948 he made a triumphant comeback with his most successful musical, Kiss Me, Kate. It w on the first Tony Award for Best Musical. Porter's other musicals include Fifty Million Frenchmen, DuBarry Was a Lady, Any thing Goes, Can-Can and Silk Stockings. His numerous hit songs include "Night an d Day","Begin the Beguine", "I Get a Kick Out of You", "Well, Did You Evah!", "I 've Got You Under My Skin", "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" and "You're the Top". He also composed scores for films from the 1930s to the 1950s, including Born to D ance (1936), which featured the song "You'd Be So Easy to Love", Rosalie (1937), which featured "In the Still of the Night"; High Society (1956), which included "True Love"; and Les Girls (1957). -

Mark Shaw Author 1336 El Camino Real Unit #1 Burlingame, CA 94010 [email protected] 415.940.0827

Mark Shaw Author 1336 El Camino Real Unit #1 Burlingame, CA 94010 [email protected] 415.940.0827 November 13, 2018 Mr. Cyrus R. Vance, Jr. District Attorney New York County District Attorney’s Office One Hogan Place New York, NY 10013 November 20, 2018 Re - Convening of Grand Jury to Re-Investigate Dorothy Kilgallen Murder Based on Evidence in the new book, Denial of Justice: Dorothy Kilgallen, Abuse of Power, and the Most Compelling JFK Assassination Investigation in History (enclosed) Dear Mr. Vance, Jr. In August 2017, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary including forensics pointing to barbiturate poisoning as the cause of death, an obvious staged death scene, multiple witnesses and documents indicating motive, and a prime suspect who knew facts about famed journalist Dorothy’s Kilgallen’s murder only the killer could know, your office issued the following statement to the New York Post: Following a thorough, eight-month-long investigation into the death of Dorothy Kilgallen, the [NY County] District Attorney’s Office has found no evidence from which it could be concluded that Ms. Kilgallen’s death was caused by another person. We would like to thank those who advocated on behalf of Ms. Kilgallen, because information provided by her supporters is one of the reasons why an investigation commenced 51 years after her death. This Office remains dedicated to the investigation of cold cases and, if new evidence comes to light, we will review it appropriately. We will decline further comment on this matter. Portions of the press release were included in this story on September 2, 2017: DA: ‘No evidence’ reporter investigating JFK assassination was murdered By Susan Edelman, NY Post The Manhattan District Attorney’s Office says it has “found no evidence” that newspaper reporter and TV star Dorothy Kilgallen was murdered as she dug deep into the JFK assassination. -

E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles

ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. D. No. 13 SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street - Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk- PAUL MAZURSKY RECOMMENDATIONS: A. That the City Council designate the unnumbered location situated one sidewalk square northerly of and between numbered locations 12H and 12h as shown on Sheet # 16 of Plan D-13788 for the Hollywood Walk of Fame for the installation of the name of Paul Mazursky at 6667 Hollywood Boulevard. B. Inform the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce of the Council's action on this matter. C. That this report be adopted prior to the date of the ceremony on December 13,2013. FISCAL IMPACT STATEMENT: No General Fund Impact. All cost paid by permittee. TRANSMITTALS: 1. Unnumbered communication dated November 5, 2013, from the Hollywood Historic Trust of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, biographical information and excerpts from the minutes of the Chamber's meeting with recommendations. City Council - 2- C. D. No. 13 DISCUSSION: The Walk of Fame Committee of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has submitted a request for insertion into the Hollywood Walk of Fame the name of Paul Mazursky. The ceremony is scheduled for Friday, December 13,2013 at 11:30 a.m. The communicant's request is in accordance with City Council action of October 18, 1978, under Council File No. 78-3949. Following the Council's action of approval, and upon proper application and payment of the required fee, an installation permit can be secured at 201 N. -

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle by Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle Supervising Committee Zoe Detsi, supervisor _____________ Christina Dokou, co-adviser _____________ Konstantinos Blatanis, co-adviser _____________ This doctoral dissertation has been conducted on a SSF (IKY) scholarship via the “Postgraduate Studies Funding Program” Act which draws from the EP “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning” 2014-2020, co-financed by European Social Fund (ESF) and the Greek State. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki I dress to kill, but tastefully. —Freddie Mercury Table of Contents Acknowledgements...................................................................................i Introduction..............................................................................................1 The Camp of Diva: Theory and Praxis.............................................6 Queer Audiences: Global Gay Culture, the Arena Tour Spectacle, and Fandom....................................................................................24 Methodology and Chapters............................................................38 Chapter 1 Times