Ding: the Life of Jay Norwood Darling David Leonard Lendt Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carol Raskin

Carol Raskin Artistic Images Make-Up and Hair Artists, Inc. Miami – Office: (305) 216-4985 Miami - Cell: (305) 216-4985 Los Angeles - Office: (310) 597-1801 FILMS DATE FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION ROLE 2019 Fear of Rain Castille Landon Pinstripe Productions Department Head Hair (Kathrine Heigl, Madison Iseman, Israel Broussard, Harry Connick Jr.) 2018 Critical Thinking John Leguizamo Critical Thinking LLC Department Head Hair (John Leguizamo, Michael Williams, Corwin Tuggles, Zora Casebere, Ramses Jimenez, William Hochman) The Last Thing He Wanted Dee Rees Elena McMahon Productions Additional Hair (Miami) (Anne Hathaway, Ben Affleck, Willem Dafoe, Toby Jones, Rosie Perez) Waves Trey Edward Shults Ultralight Beam LLC Key Hair (Sterling K. Brown, Kevin Harrison, Jr., Alexa Demie, Renee Goldsberry) The One and Only Ivan Thea Sharrock Big Time Mall Productions/Headliner Additional Hair (Bryan Cranston, Ariana Greenblatt, Ramon Rodriguez) (U. S. unit) 2017 The Florida Project Sean Baker The Florida Project, Inc. Department Head Hair (Willem Dafoe, Bria Vinaite, Mela Murder, Brooklynn Prince) Untitled Detroit City Yann Demange Detroit City Productions, LLC Additional Hair (Miami) (Richie Merritt Jr., Matthew McConaughey, Taylour Paige, Eddie Marsan, Alan Bomar Jones) 2016 Baywatch Seth Gordon Paramount Worldwide Additional Hair (Florida) (Dwayne Johnson, Zac Efron, Alexandra Daddario, David Hasselhoff) Production, Inc. 2015 The Infiltrator Brad Furman Good Films Production Department Head Hair (Bryan Cranston, John Leguizamo, Benjamin Bratt, Olympia -

Federal Government

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Chapter 5 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT 261 PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES George W. Bush – Texas (R) Term: Serving second term expiring January 2009. Profession: Businessman; Professional Baseball Team Owner; Texas Governor, 1995-2000. Education: Received B.S., Yale University, 1968; M.B.A., Harvard University, 1975. Military Service: Texas Air National Guard, 1968-1973. Residence: Born in New Haven, CT. Resident of Texas. Family Members: Wife, Laura Welch Bush; two daughters. www.whitehouse.gov VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES Richard B. Cheney – Wyoming (R) Term: Serving second term expiring January 2009. Profession: Public Official; White House Chief of Staff to President Gerald Ford, 1975-1977; U.S. Congressman, Wyoming, 1979-1989; Secretary of Defense, 1989-1993; Chief Executive Officer of the Halliburton Company. Education: Received B.A., University of Wyoming, 1965; M.A., University of Wyoming, 1966. Residence: Born in Lincoln, NE. Resident of Wyo- ming. Family Members: Wife, Lynne V. Cheney; two daugh- ters. www.whitehouse.gov 262 IOWA OFFICIAL REGISTER U.S. SENATOR Charles E. Grassley – New Hartford (R) Term: Serving fifth term in U.S. Senate expiring January 2011. Profession and Activities: Farmer and partner with son, Robin. Member: Baptist Church, Farm Bureau, Iowa Historical Society, Pi Gamma Mu, Kappa Delta Pi, Mason, International Association of Machinists, 1962-1971. Member: Iowa House of Representatives, 1959-1975; U.S. House of Representatives, 1975-1981. Elected to U.S. Senate, 1980; reelected 1986, 1992, -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan the UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA

69- 13,912 BEDDOW, James Bellamy, 1942- ECONOMIC NATIONALISM OR INTERNATIONALISM: UPPER MIDWESTERN RESPONSE TO NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY, 1934-1940. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1969 History, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ECONOMIC NATIONALISM OR INTERNATIONALISM: UPPER MIDWESTERN RESPONSE TO NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY, 1934-1940 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JAMES BELLAMY BEDDOW Norman, Oklahoma 1969 ECONOMIC NATIONALISM OR INTERNATIONALISM: UPPER MIDWESTERN RESPONSE TO NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY, 1934-1940 APfPUVED BY L y —, DISSERTATION COMMITI^E TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE................................................... iv Chapter I. MIDWESTERN AGRICULTURE AND THE TARIFE . I II. RECIPROCAL TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM ENACTED ............................. 13 III. ORGANIZATIONAL RESPONSE TO THE RECIPROCAL TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM . 4] IV. NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY AND THE ELECTION OF I936............................. 6? V. TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM RENEWED...............96 VI. AMERICAN NATIONAL LIVE STOCK ASSOCIATION OPPOSES THE TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM.......................... 128 VII. MIDWESTERN REACTION TO TRADE AGREEMENTS WITH GREAT BRITAIN AND CANADA .............144 VIII. THE NEW DEAL PROPOSES A TRADE AGREEMENT WITH ARGENTINA................... .....182 IX. TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM RENEWED............. 200 X. CONCLUSIONS ....................................244 -

Shawn Paper Ace Editor

SHAWN PAPER ACE EDITOR FEATURES THE BROKEN HEARTS GALLERY Natalie Krinsky Tri-Star Pictures / No Trace Camping THAT AWKWARD MOMENT Tom Gormican Focus Features SHOULD’VE BEEN ROMEO Marc Bennett Phillybrook Films WHAT IS IT? Crispin Glover Volcanic Eruptions TELEVISION IN FROM THE COLD Ami Canaan Mann, Netflix / Silver Lining Entertainment Paco Cabezas & Birgitte Staermose SWEET TOOTH Jim Mickle, Robyn Grace Team Downey / Warner Bros Television / Netflix & Toa Fraser WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS Taika Waititi, Taika Waititi, Jemaine Clement, Paul Simms / FX Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2019) Jemaine Clement, Jason Woliner & Jackie Van Beck CRASHING (Seasons 2 & 3) Judd Apatow, Judd Apatow, Pete Holmes, Judah Miller / HBO Gillian Robespierre, Oren Brimer & Ryan McFaul VEEP (Season 5) Various David Mandel, Julia Louis-Dreyfus / HBO Nominated, Outstanding Single-Camera Picture Editing for a Comedy Series, Primetime Emmy Awards (2012) Nominated, Best Edited Half-Hour Series for Television, ACE Eddie Awards (2012) I FEEL BAD (Pilot) Julie Anne Robinson Amy Poehler / Paper Kite Productions / NBC MOZART IN THE JUNGLE (Season 2) Paul Weitz Paul Weitz, Jason Schwartzman, Roman Coppola / Amazon GIRLS (Seasons 1, 2, 3 & 4) Richard Shepard Lena Dunham, Judd Apatow, Jenni Konner / HBO Jamie Babbit FRIENDS FROM COLLEGE Nicholas Stoller Nicholas Stoller, Francesca Delbanco / Netflix SANTA CLARITA DIET Ruben Fleischer Victor Fresco, Tracy Katsky /Netflix MARRY ME (Pilot) Seth Gordon David Caspe, Jamie Tarses / NBC GAFFIGAN (Pilot) Seth Gordon Jim -

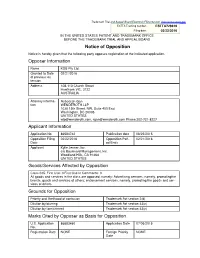

Objection To, Or Fault Found with Applicant’S Services Marketed Under

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA728619 Filing date: 02/22/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name KDB Pty Ltd. Granted to Date 02/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address 108-110 Church Street Hawthorn VIC, 3122 AUSTRALIA Attorney informa- Rebeccah Gan tion WENDEROTH LLP 1030 15th Street, NW, Suite 400 East Washington, DC 20005 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected] Phone:202-721-8227 Applicant Information Application No 86584742 Publication date 08/25/2015 Opposition Filing 02/22/2016 Opposition Peri- 02/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Kylie Jenner, Inc. c/o Boulevard Management, Inc. Woodland Hills, CA 91364 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 035. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Advertising services, namely, promotingthe brands, goods and services of others; endorsement services, namely, promoting the goods and ser- vices of others Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Dilution by blurring Trademark Act section 43(c) Dilution by tarnishment Trademark Act section 43(c) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application 86683460 Application Date 07/06/2015 No. Registration Date NONE Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark KYLIE MINOGUE DARLING Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 003. -

Downloaded Is a VH1 Rockdoc About Napster and the Digital Revolution

MAGNOLIA PICTURES AND GREAT POINT MEDIA A TROUPER PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH ZIPPER BROS FILMS AND ROXBOURNE MEDIA LIMITED Present ZAPPA A film by Alex Winter USA – 129 minutes THE FIRST ALL-ACCESS DOCUMENTARY ON THE LIFE AND TIMES OF FRANK ZAPPA Official Selection 2020 SXSW – World Premiere 2020 CPH:DOX FINAL PRESS NOTES Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: George Nicholis Tiffany Malloy Sara Tehrani Rebecca Fisher Tiffical Public Relations DDA PR Magnolia Pictures [email protected] [email protected] (212) 924-6701 201.925.1122 [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS With unfettered access to the Zappa Vault, and the archival footage contained within, ZAPPA explores the private life behind the mammoth musical career that never shied away from the political turbulence of its time. Alex Winter's assembly features appearances by Frank's widow Gail Zappa and several of Frank's musical collaborators including Mike Keneally, Ian Underwood, Steve Vai, Pamela Des Barres, Bunk Gardner, David Harrington, Scott Thunes, Ruth Underwood, Ray White and others. 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT – ALEX WINTER It seemed striking to me and producer Glen Zipper that there had yet to be a definitive, all-access documentary on the life and times of Frank Zappa. We set out to make that film, to tell a story that is not a music doc, or a conventional biopic, but the dramatic saga of a great American artist and thinker; a film that would set out to convey the scope of Zappa’s prodigious and varied creative output, and the breadth of his extraordinary personal and political life. -

Sunflower April 21, 1967

Afro-American Groap Reviews Vote Process by Kris Burgerliaff Highlighting the Wednesday problems confronting the mem meeting of a group of non-white bers as a whole. students was a proposal which, Dtmald Hughes, WSU math In if granted, will change next year's structor, and Bob Blackwell, method of electing cheerleaders. leader of the recent rent strike The proposal requests that the at the Sunflower apar^tments, cheerleaders be chosen by six were the featued speakers at football players, four basketball Wednesday’s meeting. players, the SGA President, and In his lecture, Hughes pointed three students not in SGA but out that his generation of “free to be chosen by the SGA Presi dom fighters* was born in 1955 dent. and died In 1964. He stated his Each team, football and basket hopes that a new id«i and a new ball, will choose the players group of "freedom fighters* Is they wish to represent them by now being born. open balloting. He went on to describe the Thursday was selected as the problems his generation teced. date that the new proposal was Their problems, he stated, were to be submitted to various campus much same as the ones the administrators and the Human students at WSU are now ex Relations Committee. Saturday, periencing. Describing his gen April 29, was set as the dead eration’s method of protesting, Hughes said that they believed SEVENTY FIVE - stMiMitt attM M WeAittdiy’t iMttniig ditcuit propotilt to lubmlt to ttio line for die administration to ap H prove the proposal. that suffereing would be redemp adminittration, and to orpnizo a now eampuo group, the Afro-Amorican Study Group. -

Senate, Severally with an Amend 271L by Mr

1942 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SEN~TE · 3641 By Mr. O'BRIEN of Michigan: bear, making us mindful only of the suf S. 2212 . An act to suspend during war or H. J . Res. 306. Joint resolution to amend ferings of others, that we may lose the a national emergency declared by Congress or the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, fiscal selfish longings and the vain regrets of by the President the provisions of section year 1942, by providing for a 15-percimt in 322 of the act of June 30, 1932, as amended, crease in wages for all persons employed on days agone in the love which is of Thee relating to certain leases; and projects of the Work Projects Administration; and which, indeed, Thou art. -we hum · S. 2399 . An act to amend the act entitled to the Committee on Appropriations. bly .offer our petitions in the Name and "An act to require the registration of cer for the sake of Jesus Christ, Thy Son, our tain persons employed by agencies to dissemi Lord. Amen. · nate propaganda in the United States, and PETITIONS, ETC. for other purposes,'' approved June 8, 1938, THE JOURNAL as amended. ·Under clause 1 of rule XA.'1I, petitions On motion of Mr. BARKLEY, and by and papers were laid on the Clerk's desk The message also announced that the unanimous consent, the reading of the House had passed the following bills of and referred as follows: Journal of the proceedings of the calen the Senate, severally with an amend 271L By Mr. FENTON: Petition of Miss S. -

October 1-3, 2017 Greetings from Delta State President William N

OCTOBER 1-3, 2017 GREETINGS FROM DELTA STATE PRESIDENT WILLIAM N. LAFORGE Welcome to Delta State University, the heart of the Mississippi Delta, and the home of the blues! Delta State provides a wide array of educational, cultural, and athletic activities. Our university plays a key role in the leadership and development of the Mississippi Delta and of the State of Mississippi through a variety of partnerships with businesses, local governments, and community organizations. As a university of champions, we boast talented faculty who focus on student instruction and mentoring; award-winning degree programs in business, arts and sciences, nursing, and education; unique, cutting-edge programs such as aviation, geospatial studies, and the Delta Music Institute; intercollegiate athletics with numerous national and conference championships in many sports; and a full package of extracurricular activities and a college experience that help prepare our students for careers in an ever-changing, global economy. Delta State University’s annual International Conference on the Blues consists of three days of intense academic and scholarly activity, and includes a variety of musical performances to ensure authenticity and a direct connection to the demographics surrounding the “Home of the Delta Blues.” Delta State University’s vision of becoming the academic center for the blues — where scholars, musicians, industry gurus, historians, demographers, and tourists come to the “Blues Mecca” — is becoming a reality, and we are pleased that you have joined us. I hope you will engage in as many of the program events as possible. This is your conference, and it is our hope that you find it meaningful. -

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle by Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle Supervising Committee Zoe Detsi, supervisor _____________ Christina Dokou, co-adviser _____________ Konstantinos Blatanis, co-adviser _____________ This doctoral dissertation has been conducted on a SSF (IKY) scholarship via the “Postgraduate Studies Funding Program” Act which draws from the EP “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning” 2014-2020, co-financed by European Social Fund (ESF) and the Greek State. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki I dress to kill, but tastefully. —Freddie Mercury Table of Contents Acknowledgements...................................................................................i Introduction..............................................................................................1 The Camp of Diva: Theory and Praxis.............................................6 Queer Audiences: Global Gay Culture, the Arena Tour Spectacle, and Fandom....................................................................................24 Methodology and Chapters............................................................38 Chapter 1 Times -

Edición Impresa

Deportes Páginas 12 a 15 VICKY,VETADA EUROCOPA ALEJANDRO Los rivales de BLANCO POR CHICA España también El presidente del Timonel todo el año,ahora no la han flojeado en COE estuvo ayer dejan competir con hombres en los Nacionales. sus amistosos en 20minutos.es La crisis dispara en la región las compras El primer diario que no se vende con tarjeta de crédito Martes 3 JUNIO DE 2008. AÑO IX. NÚMERO 1943 En 2007 sumaron 10.000 millones de euros, y este año van camino de 12.000 milones. Elnúmerode‘plásticos’expedidos ha crecido un 15% en un año. Muchasfamilias Sólo un ex concejal de Madrid es condenado por el ‘caso Funeraria’ ya pagan a crédito no sólo bienes duraderos, sino incluso la cesta de la compra. 2 Es Luis María Huete. El resto de implicados, entre ellos otros dos ex ediles, han sido absueltos. 3 Más de 5.000 universitarios logran becas Larevista de la Comunidad por su rendimiento En las categorías Excelencia, Erasmus y Disca- pacidad. Los primeros, 4.500 euros cada uno. 4 Multa de 60.000 euros al Sermas por un bebé que contrajo hepatitis C en La Paz El contagio se produjo en 1990, porque el centro no aplicó los marcadores que detectan el virus. 3 ! O L A S Á P Las matriculaciones de coches cayeron un 24% en mayo respecto al pasado año Las ventas de turismos han bajado una media de un 14,3% en los primeros cinco meses de 2008. 6 HOUSE SE DESPIDE ENFERMO La popular serie de televisión llega esta noche al final de su cuarta temporada,mu- Costa dice que al PP le cho más corta de lo previsto.Y el doctor House es,además de médico,paciente.