The Neuron Doctrine, the Mind, and the Arctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V O L N E Y P. G a Y R E a D I N G F R E U D

VOLNEY P. GAY READING FREUD Psychology, Neurosis, and Religion READING FREUD READING FREUD %R American Academy of Religion Studies in Religion Charley Hardwick and James O. Duke, Editors Number 32 READING FREUD Psychology, Neurosis, and Religion by Volney P. Gay READING FREUD Psychology, Neurosis, and Religion VOLNEY P. GAY Scholars Press Chico, California READING FREUD Psychology, Neurosis, and Religion by Volney P. Gay ©1983 American Academy of Religion Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Gay, Volney Patrick. Reading Freud. (Studies in religion / American Academy of Religion ; no. 32) 1. Psychoanalysis and religion. 2. Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939. 3. Religion—Controversial literature—History. I. Title. II. Series: Studies in Religion (American Academy of Religion) ; no. 32. BF175.G38 1983 200\1'9 83-2917 ISBN 0-89130-613-7 Printed in the United States of America for Barbara CONTENTS Acknowledgments viii Introduction ix Why Study Freud? Freud and the Love of Truth The Goals of This Book What This Book Will Not Do How to Use This Book References and Texts I Freud's Lectures on Psychoanalysis 1 Five Lectures on Psycho-analysis (SE 11) 1909 Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis (SE 15 & 16) 1915-16 II On the Reality of Psychic Pain: Three Case Histories 41 Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria (SE 7) 1905 "Dora" Notes Upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis (SE 10) 1909 "Rat Man" From the History of an Infantile Neurosis (SE 17) 1918 "Wolf Man" III The Critique of Religion 69 "The Uncanny" (SE 17) 1919 Totem and Taboo (SE 13) 1912-13 Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (SE 18) 1921 The Future of an Illusion (SE 21) 1927 Moses and Monotheism (SE 23) 1939 References Ill Index 121 Acknowledgments I thank Charley Hardwick and an anonymous reviewer, Peter Homans (University of Chicago), Liston Mills (Vanderbilt), Sarah Gates Campbell (Peabody-Vanderbilt), Norman Rosenblood (McMaster), and Davis Perkins and his colleagues at Scholars Press for their individual efforts on behalf of this book. -

Cajal's Law of Dynamic Polarization: Mechanism and Design

philosophies Article Cajal’s Law of Dynamic Polarization: Mechanism and Design Sergio Daniel Barberis ID Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Instituto de Filosofía “Dr. Alejandro Korn”, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, PO 1406, Argentina; sbarberis@filo.uba.ar Received: 8 February 2018; Accepted: 11 April 2018; Published: 16 April 2018 Abstract: Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the primary architect of the neuron doctrine and the law of dynamic polarization, is considered to be the founder of modern neuroscience. At the same time, many philosophers, historians, and neuroscientists agree that modern neuroscience embodies a mechanistic perspective on the explanation of the nervous system. In this paper, I review the extant mechanistic interpretation of Cajal’s contribution to modern neuroscience. Then, I argue that the extant mechanistic interpretation fails to capture the explanatory import of Cajal’s law of dynamic polarization. My claim is that the definitive formulation of Cajal’s law of dynamic polarization, despite its mechanistic inaccuracies, embodies a non-mechanistic pattern of reasoning (i.e., design explanation) that is an integral component of modern neuroscience. Keywords: Cajal; law of dynamic polarization; mechanism; utility; design 1. Introduction The Spanish microanatomist and Nobel laureate Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934), the primary architect of the neuron doctrine and the law of dynamic polarization, is considered to be the founder of modern neuroscience [1,2]. According to the neuron doctrine, the nerve cell is the anatomical, physiological, and developmental unit of the nervous system [3,4]. To a first approximation, the law of dynamic polarization states that nerve impulses are exactly polarized in the neuron; in functional terms, the dendrites and the cell body work as a reception device, the axon works as a conduction device, and the terminal arborizations of the axon work as an application device. -

The Churchlands' Neuron Doctrine: Both Cognitive and Reductionist

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231998559 The Churchlands' neuron doctrine: Both cognitive and reductionist Article in Behavioral and Brain Sciences · October 1999 DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X99462193 CITATIONS READS 2 20 1 author: John Sutton Macquarie University 139 PUBLICATIONS 1,356 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by John Sutton on 06 August 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. The Churchlands’ neuron doctrine: both cognitive and reductionist John Sutton Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22 (1999), 850-1. [email protected] http://johnsutton.net/ Commentary on Gold & Stoljar, ‘A Neuron Doctrine in the Philosophy of Neuroscience’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22 (1999), 809-869: full paper and commentaries online at: http://www.stanford.edu/~paulsko/papers/GSND.pdf Abstract: According to Gold and Stoljar, one cannot both consistently be reductionist about psychoneural relations and invoke concepts developed in the psychological sciences. I deny the utility of their distinction between biological and cognitive neuroscience, suggesting that they construe biological neuroscience too rigidly and cognitive neuroscience too liberally. Then I reject their characterization of reductionism: reductions need not go down past neurobiology straight to physics, and cases of partial, local reduction are not neatly distinguishable from cases of mere implementation. Modifying the argument from unification-as-reduction, I defend a position weaker than the radical, but stronger than the trivial neuron doctrine. -

A Bridge Between Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience: an Overview

1 ISSN 2693-2490 A Bridge between Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience: An Overview of the Neurobiological Effects of Psychoanalytical Psychotherapy Journal of Psychology and Neuroscience Research Article Diego Cohen, MD. PhD *Correspondence author Diego Cohen, MD. PhD Professor of Psychiatry University of Buenos Aries Medical Collage Professor of Psychiatry University of Buenos Aries Medical Collage Submitted : 17 Jun 2021 ; Published : 1 Jul 2021 Abstract This study sets out to investigate the mechanisms by which psychoanalytical psychotherapy can induce neurobiological changes. From Neuroscience which, in accordance with his thinking at the time, Freud never disregarded, the concepts of neuronal plasticity, enriched environment and the neurobiological aspects of the attachment process. From Psychoanalysis, the theory of transference, M. Mahler’s psychological evolution model, the concept of the regulating function of the self-objects and Winnicott’s holding environment concept. Together these provide a useful bridge toward the understanding of the neurobiological changes resulting from psychoanalytical psychotherapy. One concludes that psychoanalytical psychotherapy, through transference, acts as a new model of object relation and learning which furthers the development of certain brain areas, specifically, the right hemisphere, and the prefrontal and limbic cortices, which have a regulating function on affects. Keywords : Transference, Neurobiology, Attachment, Neuroscience Informed Therapy. Introduction In this study my aim is to provide -

Richard Scheller and Thomas Südhof Receive the 2013 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award

Richard Scheller and Thomas Südhof receive the 2013 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award Jillian H. Hurst J Clin Invest. 2013;123(10):4095-4101. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI72681. News Neural communication underlies all brain activity. It governs our thoughts, feelings, sensations, and actions. But knowing the importance of neural communication does not answer a central question of neuroscience: how do individual neurons communicate? We know that communication between two neurons occurs at specialized cell junctions called synapses, at which two communicating neurons are separated by the synaptic cleft. The presynaptic neuron releases chemicals, known as neurotransmitters, into the synaptic cleft in which neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the surface of the postsynaptic neuron. Neurotransmitter release occurs in response to an action potential within the sending neuron that induces depolarization of the nerve terminal and causes an influx of calcium. Calcium influx triggers the release of neurotransmitters through a specialized form of exocytosis in which neurotransmitter-filled vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane of the presynaptic nerve terminal in a region known as the active zone, spilling neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft. By the 1950s, it was clear that brain function depended on chemical neurotransmission; however, the molecular activities that governed neurotransmitter release were virtually unknown until the early 1990s. This year, the Lasker Foundation honors Richard Scheller (Genentech) and Thomas Südhof (Stanford University School of Medicine) for their “discoveries concerning the molecular machinery and regulatory mechanisms that underlie the rapid release of neurotransmitters.” Over the course of two decades, Scheller […] Find the latest version: https://jci.me/72681/pdf News Richard Scheller and Thomas Südhof receive the 2013 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award Neural communication underlies all Setting the stage um-driven action potentials elicited neu- brain activity. -

Sigmund Freud Papers

Sigmund Freud Papers A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress Digitization made possible by The Polonsky Foundation Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2015 Revised 2016 December Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004017 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm80039990 Prepared by Allan Teichroew and Fred Bauman with the assistance of Patrick Holyfield and Brian McGuire Revised and expanded by Margaret McAleer, Tracey Barton, Thomas Bigley, Kimberly Owens, and Tammi Taylor Collection Summary Title: Sigmund Freud Papers Span Dates: circa 6th century B.C.E.-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1871-1939) ID No.: MSS39990 Creator: Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939 Extent: 48,600 items ; 141 containers plus 20 oversize and 3 artifacts ; 70.4 linear feet ; 23 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in German, with English and French Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Founder of psychoanalysis. Correspondence, holograph and typewritten drafts of writings by Freud and others, family papers, patient case files, legal documents, estate records, receipts, military and school records, certificates, notebooks, a pocket watch, a Greek statue, an oil portrait painting, genealogical data, interviews, research files, exhibit material, bibliographies, lists, photographs and drawings, newspaper and magazine clippings, and other printed matter. The collection documents many facets of Freud's life and writings; his associations with family, friends, mentors, colleagues, students, and patients; and the evolution of psychoanalytic theory and technique. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. -

From the Neuron Doctrine to Neural Networks

LINK TO ORIGINAL ARTICLE LINK TO INITIAL CORRESPONDENCE other hand, one of my mentors, David Tank, argued that for a true understanding of a On testing neural network models neural circuit we should be able to actu- ally build it, which is a stricter definition Rafael Yuste of a successful theory (D. Tank, personal communication) Finally, as mentioned in In my recent Timeline article, I described existing neural network models have enough the Timeline article, one will also need to the emergence of neural network models predictive value to be considered valid or connect neural network models to theories as an important paradigm in neuroscience useful for explaining brain circuits.” (REF. 1)). and facts at the structural and biophysical research (From the neuron doctrine to neu- There are many exciting areas of progress levels of neural circuits and to those in cog- ral networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 487–497 in current neuroscience detailing phenom- nitive sciences as well, for proper ‘scientific (2015))1. In his correspondence (Neural enology that is consistent with some neural knowledge’ to occur in the Kantian sense. networks in the future of neuroscience network models, some of which I tried to research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. http://dx.doi. summarize and illustrate, but at the same Rafael Yuste is at the Neurotechnology Center and org/10.1038/nrn4042 (2015))2, Rubinov time we are still far from a rigorous demon- Kavli Institute of Brain Sciences, Departments of provides some thoughtful comments about stration of any neural network model with Biological Sciences and Neuroscience, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027, USA. -

Neuron: Electrolytic Theory & Framework for Understanding Its

Neuron: Electrolytic Theory & Framework for Understanding its operation Abstract: The Electrolytic Theory of the Neuron replaces the chemical theory of the 20th Century. In doing so, it provides a framework for understanding the entire Neural System to a comprehensive and contiguous level not available previously. The Theory exposes the internal workings of the individual neurons to an unprecedented level of detail; including describing the amplifier internal to every neuron, the Activa, as a liquid-crystalline semiconductor device. The Activa exhibits a differential input and a single ended output, the axon, that may bifurcate to satisfy its ultimate purpose. The fundamental neuron is recognized as a three-terminal electrolytic signaling device. The fundamental neuron is an analog signaling device that may be easily arranged to process pulse signals. When arranged to process pulse signals, its axon is typically myelinated. When multiple myelinated axons are grouped together, the group are labeled “white matter” because of their translucent which scatters light. In the absence of myelination, groups of neurons and their extensions are labeled “dark matter.” The dark matter of the Central Nervous System, CNS, are readily divided into explicit “engines” with explicit functional duties. The duties of the engines of the Neural System are readily divided into “stages” to achieve larger characteristic and functional duties. Keywords: Activa, liquid-crystalline, semiconductors, PNP, analog circuitry, pulse circuitry, IRIG code, 2 Neurons & the Nervous System The NEURONS and NEURAL SYSTEM This material is excerpted from the full β-version of the text. The final printed version will be more concise due to further editing and economical constraints. -

Significant Landmarks in the History of Aphasia and Its Therapy

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER© Jones & Bartlett2 Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett© Involved Channel/Shutterstock Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Significant© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC Landmarks© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC inNOT FOR the SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONHistory ofNOT AphasiaFOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlettand Learning, Its LLC Therapy© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEChris OR Code DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION OBJECTIVES© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION The reader will be able to: 1. Understand the origins of different classifications of aphasia. 2. Compare models of aphasia that have emerged in the history of aphasia. 3.© JonesAppreciate & thatBartlett the history Learning, of aphasia LLC is influenced by social and ©political Jones developments & Bartlett in Learning,different countries. LLC 4. Name the main protagonists in the history of aphasia. 5.NOT Identify FOR the SALE main events OR DISTRIBUTION in the history of aphasia. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 6. Identify the main shifts in approach to the treatment of aphasia throughout the history of aphasia. 7. Understand where ideas about the nature of aphasia originated. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION “History doesn’t repeat itself. At best it sometimes Plato’s view, that the mind was located in the head rhymes.” contrasted with Aristotle’s idea that it was located in the heart. -

Freud, S. (1923). the Ego and the Id. the Standard Edition Of

Freud, S. (1923). The Ego and the Id. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923- 1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works, 1-66 The Ego and the Id Sigmund Freud This Page Left Intentionally Blank - 1 - Copyrighted Material. For use only by UPENN. Reproduction prohibited. Usage subject to PEP terms & conditions (see terms.pep-web.org). Editor's Introduction to "The Ego and the Id" James Strachey (a) German Editions: 1923 Das Ich Und Das Es Leipzig, Vienna and Zurich: Internationaler Psycho-analytischer Verlag. Pp. 77. 1925 Das Ich Und Das Es G.S., 6, 351-405. 1931 Das Ich Und Das Es Theoretische Schriften, 338-91. 1940 Das Ich Und Das Es G.W., 13, 237-289. (b) English Translation:: The Ego and the Id 1927 London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho- Analysis. Pp. 88. (Tr. Joan Riviere.) The present is a very considerably modified version of the one published in 1927. This book appeared in the third week of April, 1923, though it had been in Freud's mind since at least the previous July (Jones, 1957, 104). On September 26, 1922, at the Seventh International Psycho-Analytical Congress, which was held in Berlin and was the last he ever attended, he read a short paper with the title ‘Etwas vom Unbewussten [Some Remarks on the Unconscious]’, in which he foreshadowed the contents of the book. An abstract of this paper (which was never itself published) appeared that autumn in the Int. Zeitschrift Psychoanal., 5 (4), 486,1 and, although there is no certainty that it was written by Freud himself, it is worth while recording it: ‘Some Remarks on the Unconscious’ ‘The speaker repeated the familiar history of the development of the concept “‘unconscious” in psycho-analysis. -

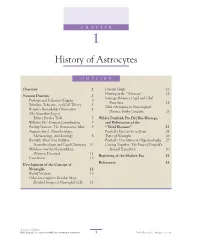

Chapter 1. History of Astrocytes

CHAPTER 1 History of Astrocytes OUTLINE Overview 2 Camillo Golgi 16 Naming of the “Astrocyte” 18 Neuron Doctrine 2 Santiago Ramón y Cajal and Glial Purkinje and Valentin’s Kugeln 2 Functions 18 Scheiden, Schwann, and Cell Theory 3 Glial Alterations in Neurological Remak’s Remarkable Observation 4 Disease: Early Concepts 21 The Neurohistology of Robert Bentley Todd 5 Wilder Penfield, Pío Del Río-Hortega, Wilhelm His’ Seminal Contributions 7 and Delineation of the Fridtjof Nansen: The Renaissance Man 8 “Third Element” 22 Auguste Forel: Neurohistology, Penfield’s Idea to Go to Spain 24 Myrmecology, and Sexology 8 Types of Neuroglia 26 Rudolph Albert Von Kölliker: Penfield’s Description of Oligodendroglia 27 Neurohistologist and Cajal Champion 10 Coming Together: The Fruit of Penfield’s Waldeyer and the Neuronlehre Spanish Expedition 30 (Neuron Doctrine) 11 Beginning of the Modern Era 33 Conclusion 12 References 34 Development of the Concept of Neuroglia 12 Rudolf Virchow 12 Other Investigators Develop More Detailed Images of Neuroglial Cells 15 Astrocytes and Epilepsy DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802401-0.00001-6 1 © 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 2 1. HIStorY OF AStrocYTES OVERVIEW In this introduction to the history of astrocytes, we wish to accomplish the following goals: (1) contextualize the evolution of the concept of neuroglia within the development of cell theory and the “neuron doctrine”; (2) explain how the concept of neuroglia arose and evolved; (3) provide an interesting overview of some of the investigators involved in defin- ing the cell types in the central nervous system (CNS); (4) select the interaction of Wilder Penfield and Pío del Río-Hortega for a more in-depth historical vignette portraying a critical period during which glial cell types were being identified, described, and separated; and (5) briefly summarize further developments that presaged the modern era of neurogliosci- ence. -

The Language of Boundaries

Session 1: The Language of Boundaries There are 20 films, 40 ideas, and 4 architectures to cover in this survey of how boundaries are used in human life and expression, and there is no logical order that sets out plainly an obvious starting point of “basics” on to which more complicated issues can be later added. Rather, we have to “start in the middle” wherever we start, because everyplace is a center, out from which thought can move towards the horizon, which keeps receding the closer we get to it. With this in mind, it’s always a good idea to start with something that is both familiar and mysterious at the same time (this is, one should also note, Freud’s formula for the uncanny). We work within a physical field that is mostly spatial, involving the visual arts, landscape, architecture, film, travel, etc. But, this is not a simplification. In themental field of our project — defined primarily by a few key philosophers (Vico, Hegel, Cassirer) and psychoanalysts (Freud, La- can) — spatiality and temporality are intrinsic to thought and human being as such. We could say that “dimensional- ity” is something that humans construct once anxiety, the fuel for that construction, is given certain qualities; and that because they have some latitude over how it is constructed, personalities and cultures turn out to be quite unique, with the only common factor being the construction process rather than the end result. Zeno. Everyone knows the famous paradoxes of this ancient Greek philosopher. A fast runner (Achil- BASIC DIAGRAMS les) cannot beat out the tortoise; an arrow cannot reach the target; etc.