English Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FMI Wholesale 2006 Price List

FMI Wholesale 2006 Price List T 800.488.1818 · F 480.596.7908 Welcome to the launch of FMI Wholesale, a division of Fender Musical Instruments Corp. We are excited to offer you our newest additions to our family of great brands and products. Meinl Percussion, Zildjian®, Tribal Planet, Hal Leonard®, Traveler Guitar, Practice Tracks, Pocket Rock-It, are just a few of the many great names that you’ll find in this Winter Namm Special Product Guide. You’ll find page after page of new and exciting profit opportunities to take advantage of as we welcome the new year. In the coming weeks, you will also be receiving our brand new product catalog showcasing all of the great products that FMI Wholesale will be offering to you in 2006. Our goal, along with that of our strategic business partners, is to provide you with a new and easy way to do business. In the enduring Fender tradition, we aim to provide best-in-class products, superior service and our ongoing commitment to excellence that will be second to none. Our programs will be geared towards your profitability, so in the end, doing business with FMI Wholesale will always make good sense. Thank you for the opportunity to earn your business. We look forward to working with you in 2006. Sincerely, The FMI Wholesale Sales and Marketing Team Dealer Dealer Number Contact PO Number Ship To Date Terms: Open Account GE Flooring Notes FREIGHT POLICY: 2006 brings new opportunities for savings in regards to freight. To maximize your profitability‚ our newly revamped freight program continues to offer freight options for both small and large goods. -

HYPEBEAST UNVEILS FENDER® X HYPEBEAST STRATOCASTER

HYPEBEAST UNVEILS FENDER® x HYPEBEAST STRATOCASTER Download assets HERE Hypebeast today announces the launch of the HYPEBEAST Stratocaster®, presented in collaboration with Fender®, the iconic global guitar brand. Hypebeast shares strong bonds with a global network of content creators, and is dedicated to maintaining close interactions with established musicians across genres, as well as discovering emerging talent and bringing that to Hypebeast’s cultural realm. Constantly inspired by such meaningful connections, Hypebeast is thrilled to be joining hands with Fender to present this vintage-style guitar in Hypebeast’s signature navy. “Fender has always been closely connected to musical culture since its founding in 1946. Similarly, Hypebeast is one of the most influential online media in lifestyle and culture. Through this collaboration, we’re looking forward to bringing music closer to other cultural realms, as we share a passion for music amongst a generation immersed in fashion and lifestyle,” said Edward Cole President of APAC, Fender Music Corporation. www.hypebeast.com [email protected] Page 1 of 2 The model is based on the globally acclaimed Made in Japan Stratocaster featuring a 9.5" radius and 22 Medium Jumbo frets, delivering a sophisticated playability with modern feel optimal for any musical genres and playing style. The guitar painted in Hypebeast’s signature navy color from top to bottom - including the fingerboard and headstock - is sure to catch the attention of any culture-sensitive player. This special edition guitar is available exclusively at Fender.com in Japan, US and UK regions, as well as HBX.com in extremely limited quantities. To read full product specifications, please visit fender.com for more information. -

Identities Bought and Sold, Identity Received As Grace

IDENTITIES BOUGHT AND SOLD, IDENTITY RECEIVED AS GRACE: A THEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF AND ALTERNATIVE TO CONSUMERIST UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE SELF By James Burton Fulmer Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion December, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Paul DeHart Professor Douglas Meeks Professor William Franke Professor David Wood Professor Patout Burns ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the members of my committee—Professors Paul DeHart, Douglas Meeks, William Franke, David Wood, and Patout Burns—for their support and guidance and for providing me with excellent models of scholarship and mentoring. In particular, I am grateful to Prof. DeHart for his careful, insightful, and challenging feedback throughout the writing process. Without him, I would have produced a dissertation on identity in which my own identity and voice were conspicuously absent. He never tried to control my project but rather always sought to make it more my own. Special thanks also to Prof. Franke for his astute observations and comments and his continual interest in and encouragement of my project. I greatly appreciate the help and support of friends and family. My mom, Arlene Fulmer, was a generous reader and helpful editor. James Sears has been a great friend throughout this process and has always led me to deeper thinking on philosophical and theological matters. Jimmy Barker, David Dault, and Eric Froom provided helpful conversation as well as much-needed breaks. All my colleagues in theology helped with valuable feedback as well. -

Businessdirectory Call to Reserve Ad Space: 972-422-SELL

starlocalmedia.com The Colony Courier Leader Sunday, March 16, 2014 Home Delivery: 972-424-9504 9A OUT OF TOWN SCHOOLS GARAGE PROPERTY PETS/LIVE- TRANSPORTA- AREA AREA SALES Vacation/Full Time STOCK TION PLACE YOUR WANNA BE A Bass Capitol For Lease: 2 BR, 1 Bath. Celina...... $775. FIREFIGHTER/ of Texas - HELP WANTED For Lease: Office Warehouse. Pilot Point. EMT IN LESS THAN AREA Lake Fork. Beautiful, DOGS MOTORCYCLES 4,200 SF... $1,750/mo 6 MONTHS? improved lot with low For Lease: Medical Office. Frisco. 5,436 SF. Texas commission Estate Sale: Fri 14 & monthly payment. Call 2005 Honda CLASSIFIED AD Available Now. on Fire Protection & Sat 15. 321 Maverick now! 903-878-7265 Shadow Spirit 750 Call 972-668-5596 or 214-549-5809 EMT Certification Trail, Oak Point. 9K miles, Like brand ONLINE. enrolling now for Household furniture, new, w/bags, wind- day & evening Antiques and yard shield $3400 MALTESE PUPPIES classes. items. 8 am-3 pm 972.743.7291 www.StarLocalMedia.com Baby Faced, Tea Cup & For more info. Toy Sized. Reg’d, Shots & Call 903-564-3862 NOTICES NOTICES Worming, 1-yr Health P.O. Box 3063, Sher- Guar. Male & Female. WAREHOUSE/ WAREHOUSE/ WAREHOUSE/ man, Tx 75091 LEWISVILLE SHIPPING SHIPPING SHIPPING www.hazco-fire.com LEGAL NOTICE VA APPROVED ESTATE SALE 433 MULLINS some WAAREHOUSEREHOUSE SALE OF 5X5 Unit # B20 JENNI Need Antiques. Inside Sale. tuxedos RDER ELECTOR ABBE, 10x10 Unit # 21 BRENDA CASE, NEVER GO OUT OF O S 10x10 Unit # 29 GLENN JEWELL Stan- Employees? 8am-4pm, March 22 SOLID WHITE McKinney, TX. -

Electric Guitars 51

ELECTRIC GUITARS 51. US Masters, Vector, Blue 1. Alvarez Classic Electric, Natural 52. Vester Concert Series, Black/Gold Fractal, Upg 2. Alvarez Classic Electric, Sunburst Sinvader Bridge Hum, Dual Rail Neck 3. Alvarez Electric, White 53. Washburn CT2, Black (upgraded pickups) 4. Alvarez Regulator, Green 54. Washburn CT5, Deluxe, gorgeous figured Blue 5. Bolt USA, SS, Graphic 55. Washburn_JV2, Natural 6. Brian Moore, I8.13, Green 56. Washburn_JV Jr, Flourescent Orange 7. Brian Moore, I2.13, YellowFigured 57. Washburn JB100, White 8. CB Strat guitar, White 58. Washburn KC44V, Green/ Black design 9. CC Clark, Natural 59. Washburn MR250, Red Florentine Figured 10. Charvel 275 Deluxe, Red 60. Washburn N6 (needs assembly) 11. Charvel CX390, Black 61. Washburn P290, Green Transluscent 12. ESP EC100-QM, Red 62. Washburn P290, Blue Green Transluscent 13. Fender Strat Spec. Ed., MIM, Candy Apple Red 63. Washburn P4 Luthier, Natural 14. Fender Strat, MIJ, HSS, Black 64. Washburn Pilsen WI70, Root Beer, Paint Relic’d 15. Fender Squier Showmaster Skull & Crossbones 65. Washburn RR300, Red 16. Fender Squier II, Black Relic’d 66. Washburn SBT-21, Black 17. Fender Squier Bullet, Red w SDuncan Distortion 67. Washburn WI64DL, Black and Gold 18. First Act VW Garage Master SpecEd, W W pg 68. Washburn WI64, Black 19. First Act VW Garage Master Spec Ed, W B pg 69. Washburn WI64, Black, Upg Carvin PU’s 20. Godin G5000, Black (option: Roland Synth PU) 70. Washburn WI66NC, Ebony Figured, Boogie Bros 21. Greco Hollow Body (Jap), Brown 71. Washburn WI66 Pro, Blue Figured Top 22. Harmony solid body electric, White 72. -

The Fender Custom Shop and “Blackie” Your Questions Answered…

The Fender Custom Shop and “Blackie” Your questions answered… A few days before the launch of the Fender Eric Clapton “Blackie” Reissue, Mike Eldred – Director of Sales and Marketing for the Fender Custom Shop, was interviewed by Guitar Center for his personal account of the “Blackie” Reissue project. GC: So Mike, what’s your role at Fender, and in the Custom Shop specifically? Mike: I’m Director of Sales and Marketing for the FMIC Custom Division, and that encompasses all brands: Tacoma, Guild, Gretsch, Fender, Charvel, Jackson, and the amplifiers. GC: What is it about “Blackie” that makes it so special, even within that special world? Mike: It’s an iconic Stratocaster. The story about the guitar is really such a great story about how Eric bought the guitar--bought several guitars--and then pieced together basically just one guitar from a bunch of different parts. So he actually built the guitar, which is very unique when it comes to iconic guitars like this. A lot of times they’re just bought at a store or something like that. But here, an artist actually built the guitar, and then used it on so many different recordings, and it was so identified with Eric Clapton and his musical legacy. GC: Then, after 35 years of ownership, he offered it up for sale. What did Fender think when they heard that Guitar Center had bought Blackie at auction for almost a million dollars? Mike: Just that we were glad that it was sold to someone we have a relationship with. The concern that we had was that somebody was going to buy it and then just lock it away and that would be that, or some private collector would buy it or something like that. -

Peter Svensson Får Platinagitarren 2017

Peter Svensson 2017-10-18 07:00 CEST Peter Svensson får Platinagitarren 2017 Låtskrivaren och gitarristen Peter Svensson får Stims utmärkelse Platinagitarren för sina framgångar som låtskrivare genom åren och under 2016. Peter Svensson var med och grundade The Cardigans och har skapat musik i mer än 20 år. Han har även varit låtskrivare åt en rad stora internationella artister. Bland de största hitsen senaste åren kan nämnas Ariana Grandes Love Me Harder (3a i USA), USA-ettan och monsterhiten Can't Feel My Face och In The Night (12 i USA), båda framförda av The Weeknd. 1992 bildade hårdrockaren Peter Svensson gruppen The Cardigans tillsammans med Magnus Sveningsson. Fyra år senare slog bandet igenom stort internationellt med världshiten "Lovefool". Världsturneer och ytterligare hits följer, såsom "My Favourite game", "Erase/Rewind" och "I need some fine wine and you, you need to be nicer". - Det känns helt fantastiskt att bli tilldelad Stims Platinagitarr!! Bara att få ingå i den skara av låtskrivare som tidigare fått utmärkelsen gör en stolt. Det är verkligen uppmuntrande och en fin bekräftelse på att det man gör uppskattas. Nu är det bara att hoppas på att jag kan leva upp till det hela och få till det igen, säger Peter Svensson. Parallellt med The Cardigans skrev Peter Svensson hits åt exempelvis Titiyo (Come Along), Lisa Miskovsky och det egna sidoprojektet Paus tillsammans med Joakim Berg från Kent. Peter Svensson har även etablerat sig som låtskrivare åt en rad stora internationella artister såsom One Direction, Ellie Goulding och The Weeknd. Bland Peters största hits de senaste åren kan nämnas Ariana Grandes Love Me Harder (3a i USA), Meghan Trainors Me Too (13e plats i USA) och USA- ettan "Can't Feel My Face" och "In The Night" (12e plats i USA), båda framförda av The Weeknd. -

Gretsch Setup Specs

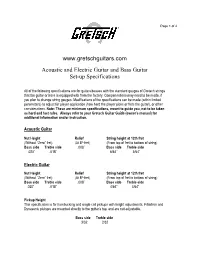

Page 1 of 2 www.gretschguitars.com Acoustic and Electric Guitar and Bass Guitar Set-up Specifications All of the following specifications are for guitars/basses with the standard gauges of Gretsch strings that the guitar or bass is equipped with from the factory. Compensations may need to be made, if you plan to change string gauges. Modifications of the specifications can be made (within limited parameters) to adjust for player application (how hard the player picks or frets the guitar), or other considerations. Note: These are minimum specifications, meant to guide you, not to be taken as hard and fast rules. Always refer to your Gretsch Guitar Guide (owner's manual) for additional information and/or instruction. Acoustic Guitar Nut Height Relief String height at 12th fret (Without “Zero” fret) (At 8th fret) (From top of fret to bottom of string) Bass side Treble side .008” Bass side Treble side .020” .018” 6/64” 5/64” Electric Guitar Nut Height Relief String height at 12th fret (Without “Zero” fret) (At 8th fret) (From top of fret to bottom of string) Bass side Treble side .008” Bass side Treble side .020” .018” 4/64” 4/64” Pickup Height This specification is for humbucking and single coil pickups with height adjustments. Filtertron and Dynasonic pickups are mounted directly to the guitar’s top, and are not adjustable. Bass side Treble side 3/32 2/32 Page 2 of 2 Bass Guitar Nut Height Relief String height at 12th fret (Without “Zero” fret) (At 8th fret) (From top of fret to bottom of string) Bass side Treble side .008” Bass side Treble side .022” .022” 4/64” 4/64” Pickup Height This specification is for humbucking and single coil pickups with height adjustments. -

From Girlfriend to Gamer: Negotiating Place in the Hardcore/Casual Divide of Online Video Game Communities

FROM GIRLFRIEND TO GAMER: NEGOTIATING PLACE IN THE HARDCORE/CASUAL DIVIDE OF ONLINE VIDEO GAME COMMUNITIES Erica Kubik A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Amy Robinson Graduate Faculty Representative Kristine Blair Donald McQuarie ii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor The stereotypical video gamer has traditionally been seen as a young, white, male; even though female gamers have also always been part of video game cultures. Recent changes in the landscape of video games, especially game marketers’ increasing interest in expanding the market, have made the subject of women in gaming more noticeable than ever. This dissertation asked how gender, especially females as a troubling demographic marking difference, shaped video game cultures in the recent past. This dissertation focused primarily on cultures found on the Internet as they related to video game consoles as they took shape during the beginning of the seventh generation of consoles, between 2005 and 2009. Using discourse analysis, this dissertation analyzed the ways gendered speech was used by cultural members to define not only the limits and values of a generalizable video game culture, but also to define the idealized gamer. This dissertation found that video game cultures exhibited the same biases against women that many other cyber/digital cultures employed, as evidenced by feminist scholars of technology. Specifically, female gamers were often perceived as less authoritative of technology than male gamers. This was especially true when the concept “hardcore” was employed to describe the ideals of gaming culture. -

Line 6 Model Gallery (Rev. C, V2.0)

Model Gallery High definition models of immortal amps and effects is what Line 6 POD HD series all about Here’s what you’ll find under the hood of your POD HD Device ____________________________________ POD HD Pro | POD HD500 | POD HD Desktop POD HD300 | POD HD400 ____________________________________ Electrophonic Online Limited Edition - Revision C Table of Contents About the Model Gallery ......................................................... 4 HD Amp Models ........................................................................ 4 Blackface Double ................................................................................................5 Hiway 100 Custom ..............................................................................................6 Super O ...............................................................................................................7 Gibtone 185 ........................................................................................................8 Tweed B-Man ......................................................................................................9 Blackface ‘Lux ...................................................................................................10 Divide 9/15 ........................................................................................................11 PhD Motorway ..................................................................................................12 Class A 15 .........................................................................................................13 -

Omstridt Prispåslag Fra Samskipnaden På Bakrommet Med Public Enemy 50 Band Kan Bli Husløse

studentavisa i Trondheim 14/2003 21. oktober - 4. november 2003 88. årgang Omstridt prispåslag fra Samskipnaden På bakrommet med Public Enemy 50 band kan bli husløse Studielånet i boks LEDER INNHOLD 14/2003 Statsbudsjettets alkymi NYHETER 3 Strid om Samskipnadens prispåslag 4 Valgtid igjen I regjeringens forslag til statsbudsjett for 2004 heter det 9 Strykerne finansierer kvalitetsreformen at hele utdanningsstipendet skal gjøres om til 13 Ridderlig studiedirektør på plass konverteringsstipend fra og med undervisningsåret 2004- 14 Hjerneforskerne er alene 2005. Hvilket betyr at hvis du stryker til eksamen, må du betale tilbake hver eneste krone du får av Lånekassen. Du har imidlertid åtte år på deg til å rette opp feilen, og dermed forvandle 40 prosent av lånet ditt til stipend. Det er ikke ordningen i seg selv som er betenkelig. Vel er den upedagogisk, og fungerer mer som en pisk enn den gulroten mange studenter trenger for å fullføre Men Origo var ikke død gradene sine. Derimot er det formålet med ordningen som Origosenterets leder Tor Bollingmo frykter for hva som kan burde få et par bjeller til å ringe i lånekassekundenes skje med det populære veiledningssenteret på Dragvoll etter hoder: Stryker du til eksamen, er du med på å redde en nyttår. Nybakt studiedirektør Hilde Skeie hevder på sin side fullfinansiering av kvalitetsreformen. at senteret skal videreføres og forbedres. Utdannings- og forskningsdepartementet (UFD), med Kristin Clemet i spissen, har heldigvis bestemt seg for å bevilge hele 517 millioner mer til implementering av 10 kvalitetsreformen, som er kostnadssatt til totalt 1,144 milliarder kroner, for neste år. Med litt mer tålmodighet REPORTASJE og planlegging hadde UFD kanskje sluppet å punge ut ekstra nå, men det er en helt annen sak. -

Jukebox Decades – 100 Hits Ultimate Soul

JUKEBOX DECADES – 100 HITS ULTIMATE SOUL Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Ain’t No Sunshine Bill Withers 01 Be My Baby The Ronettes 02 How ‘Bout Us Champaign 02 Captain Of Your Ship Reparata 03 Sexual Healing Marvin Gaye 03 Band Of Gold Freda Payne 04 Me & Mrs. Jones Billy Paul 04 Midnight Train To Georgia Gladys Knight 05 If You Don’t Know Me Harold Melvin 05 Piece of My Heart Erma Franklin 06 Turn Off The Lights Teddy Pendergrass 06 Woman In Love The Three Degrees 07 A Little Bit Of Something Little Richard 07 I Need Your Love So Desperately Peaches 08 Tears On My Pillow Johnny Nash 08 I’ll Never Love This Way Again D Warwick 09 Cause You’re Mine Vibrations 09 Do What You Gotta Do Nina Simone 10 So Amazing Luther Vandross 10 Mockingbird Aretha Franklin 11 You’re More Than A Number The Drifters 11 That’s What Friends Are For D Williams 12 Hold Back The Night The Tramps 12 All My Lovin’ Cheryl Lynn 13 Let Love Come Between Us James 13 From His Woman To You Barbara Mason 14 After The Love Has Gone Earth Wind & Fire 14 Personally Jackie Moore 15 Mind Blowing Decisions Heatwave 15 Every Night Phoebe Snow 16 Brandy The O’ Jays 16 Saturday Love Cherrelle 17 Just Be Good To Me The S.O.S Band 17 I Need You Pointer Sisters 18 Ready Or Not Here I The Delfonics 18 Are You Lonely For Me Freddie Scott 19 Home Is Where The Heart Is B Womack 19 People The Tymes 20 Birth The Peddlers 20 Don’t Walk Away General Johnson Disc Three - Title Artist Disc Four - Title Artist 01 Till Tomorrow Marvin Gaye 01 Lean On Me Bill Withers 02 Here