Morphological Types of Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Is Language Typology Possible?

Why is language typology possible? Martin Haspelmath 1 Languages are incomparable Each language has its own system. Each language has its own categories. Each language is a world of its own. 2 Or are all languages like Latin? nominative the book genitive of the book dative to the book accusative the book ablative from the book 3 Or are all languages like English? 4 How could languages be compared? If languages are so different: What could be possible tertia comparationis (= entities that are identical across comparanda and thus permit comparison)? 5 Three approaches • Indeed, language typology is impossible (non- aprioristic structuralism) • Typology is possible based on cross-linguistic categories (aprioristic generativism) • Typology is possible without cross-linguistic categories (non-aprioristic typology) 6 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Franz Boas (1858-1942) The categories chosen for description in the Handbook “depend entirely on the inner form of each language...” Boas, Franz. 1911. Introduction to The Handbook of American Indian Languages. 7 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) “dans la langue il n’y a que des différences...” (In a language there are only differences) i.e. all categories are determined by the ways in which they differ from other categories, and each language has different ways of cutting up the sound space and the meaning space de Saussure, Ferdinand. 1915. Cours de linguistique générale. 8 Example: Datives across languages cf. Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. The geometry of grammatical meaning: semantic maps and cross-linguistic comparison 9 Example: Datives across languages 10 Example: Datives across languages 11 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Peter H. Matthews (University of Cambridge) Matthews 1997:199: "To ask whether a language 'has' some category is...to ask a fairly sophisticated question.. -

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe © Council of Europe, April 2011 The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All correspondence concerning this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Director of Education and Languages of the Council of Europe (Language Policy Division) (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). The reproduction of extracts is authorised, except for commercial purposes, on condition that the source is quoted. Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe Language Policy Division Council of Europe (Strasbourg) www.coe.int/lang Contents Foreword 5 3.4.2 Piloting, pretesting and trialling 30 Introduction 6 3.4.3 Review of items 31 1 Fundamental considerations 10 3.5 Constructing tests 32 1.1 How to define language proficiency 10 3.6 Key questions 32 1.1.1 Models of language use and competence 10 3.7 Further reading 33 1.1.2 The CEFR model of language use 10 4 Delivering tests 34 1.1.3 Operationalising the model 12 4.1 Aims of delivering tests 34 1.1.4 The Common Reference Levels of the CEFR 12 4.2 The process of delivering tests 34 1.2 Validity 14 4.2.1 Arranging venues 34 1.2.1 What is validity? 14 4.2.2 Registering test takers 35 1.2.2 Validity -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

The Syntactic and Semantic Relationship in Synthetic Languages

This is the published version of the bachelor thesis: Navarro Caparrós, Raquel; van Wijk Adan, Malou, dir. The Syntactic and Semantic Relationship in Synthetic Languagues : Linear Modification in Latin and Old English. 2016. 41 pag. (838 Grau en Estudis d’Anglès i de Clàssiques) This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/164293 under the terms of the license The Syntactic and Semantic Relationship in Synthetic Languages: Linear Modification in Latin and Old English TFG – Grau d’Estudis d’Anglès i Clàssiques Supervisor: Malou van Wijk Adan Raquel Navarro Caparrós June 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Ms. Malou van Wijk Adan for her assistance and patience during the period of my research. This project would not have been possible without her guidance and valuable comments throughout. I would also like to thank all my teachers of Classical Studies and English Studies for sharing their knowledge with me throughout these four years. Finally, I wish to acknowledge my mum and my sister Ruth whose invaluable support helped me to overcome any obstacle, especially in the last two years. Without them, I am sure that I would have never been able to get where I am now. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................... ii List of Tables .................................................................................................................. iii Abstract .......................................................................................................................... -

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

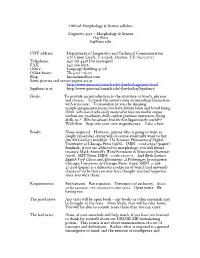

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: a Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, Thierry Poibeau, Ekaterina Shutova, Anna Korhonen To cite this version: Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, et al.. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing. 2018. hal-01856176 HAL Id: hal-01856176 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01856176 Preprint submitted on 9 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Maria Ponti∗ Helen O’Horan∗∗ LTL, University of Cambridge LTL, University of Cambridge Yevgeni Berzaky Ivan Vuli´cz Department of Brain and Cognitive LTL, University of Cambridge Sciences, MIT Roi Reichart§ Thierry Poibeau# Faculty of Industrial Engineering and LATTICE Lab, CNRS and ENS/PSL and Management, Technion - IIT Univ. Sorbonne nouvelle/USPC Ekaterina Shutova** Anna Korhonenyy ILLC, University of Amsterdam LTL, University of Cambridge Understanding cross-lingual variation is essential for the development of effective multilingual natural language processing (NLP) applications. -

Grammatical Analyticity Versus Syntheticity in Varieties of English

Language Variation and Change, 00 (2009), 1–35. © Cambridge University Press, 2009 0954-3945/09 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394509990123 1 2 3 4 Typological parameters of intralingual variability: 5 Grammatical analyticity versus syntheticity in varieties 6 7 of English 8 B ENEDIKT S ZMRECSANYI 9 Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies 10 11 12 ABSTRACT 13 Drawing on terminology, concepts, and ideas developed in quantitative morphological 14 typology, the present study takes an exclusive interest in the coding of grammatical 15 information. It offers a sweeping overview of intralingual variability in terms of 16 overt grammatical analyticity (the text frequency of free grammatical markers), 17 grammatical syntheticity (the text frequency of bound grammatical markers), and 18 grammaticity (the text frequency of grammatical markers, bound or free) in English. 19 The variational dimensions investigated include geography, text types, and real time. 20 Empirically, the study taps into a number of publicly accessible text corpora that 21 comprise a large number of different varieties of English. Results are interpreted in 22 terms of how speakers and writers seek to achieve communicative goals while 23 minimizing different types of complexity. 24 25 This study surveys language-internal variability and short-term diachronic change, 26 along dimensions that are familiar from the cross-linguistic typology of languages. 27 The terms analytic and synthetic have a long and venerable tradition in linguistics, 28 going back to the 19th century and August Wilhelm von Schlegel, who is usually 29 credited for coining the opposition (Schlegel, 1818). This is, alas, not the place to 30 even attempt to review the rich history of thought in this area (but see Schwegler, “ 31 1990:chapter 1 for an excellent overview). -

The Twilight of Structuralism in Linguistics?*

Ewa Jędrzejko Univesity of Silesia in Katowice nr 3, 2016 The Twilight of Structuralism in Linguistics?* Key words: structuralism, linguistics, methodological principles, evolution of studies on language I would like to start with some general remarks in order to avoid misunderstandings due to the title of this paper. “The question that our title / has cast in deathless bronze”1 is just a mere trigger, and a signal of reference to animated discussions held in many disci- plines of modern liberal arts: philosophy, literary studies, social sciences, aesthetics, cultural studies (just to mention areas closest to linguistics), concerning their current methodologi- cal state and future perspectives regarding theoretical research. What I mean by that is, among others, the dispute around deconstructionism being in opposition to neo-positivistic stance, as well as some views on the current situation in art expressed in the volume called Zmierzch estetyki – rzekomy czy autentyczny? [The twilight of aesthetics – alleged or true?] (Morawski, 1987),2 or problems signalled by the literary scholars in the tellingly entitled Po strukturalizmie [After structuralism] (Nycz, 1992).3 The statements included in this article are for me one out of many voices in the discus- sion on the changes observed in linguistics in the context of questions about the future of structuralism. Since in a way the situation in contemporary linguistics (including Polish linguistics) is similar. The shift in the scope of interest of linguistics and the way it is presented may -

Foreign Language Teaching and Learning Aleidine Kramer Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Learning and Teacher Education Education 2015 Foreign Language Teaching and Learning Aleidine Kramer Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected] Theresa Catalano University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Educational Methods Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Moeller, Aleidine Kramer and Catalano, Theresa, "Foreign Language Teaching and Learning" (2015). Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education. 196. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in J.D. Wright (ed.), International Encyclopedia for Social and Behavioral Sciences 2nd Edition. Vol 9 (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 2015), pp. 327-332. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.92082-8 Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. Used by permission. digitalcommons.unl.edu Foreign Language Teaching and Learning Aleidine J. Moeller and Theresa Catalano 1. Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, USA Abstract Foreign language teaching and learning have changed from teacher-centered to learner/learning-centered environments. Relying on language theories, research findings, and experiences, educators developed teaching strategies and learn- ing environments that engaged learners in interactive communicative language tasks. -

Typology, Documentation, Description, and Typology

Typology, Documentation, Description, and Typology Marianne Mithun University of California, Santa Barbara Abstract If the goals of linguistic typology, are, as described by Plank (2016): (a) to chart linguistic diversity (b) to seek out order or even unity in diversity knowledge of the current state of the art is an invaluable tool for almost any linguistic endeavor. For language documentation and description, knowing what distinctions, categories, and patterns have been observed in other languages makes it possible to identify them more quickly and thoroughly in an unfamiliar language. Knowing how they differ in detail can prompt us to tune into those details. Knowing what is rare cross-linguistically can ensure that unusual features are richly documented and prominent in descriptions. But if documentation and description are limited to filling in typological checklists, not only will much of the essence of each language be missed, but the field of typology will also suffer, as new variables and correlations will fail to surface, and our understanding of deeper factors behind cross-linguistic similarities and differences will not progress. 1. Typological awareness as a tool Looking at the work of early scholars such as Franz Boas and Edward Sapir, it is impossible not to be amazed at the richness of their documentation and the insight of their descriptions of languages so unlike the more familiar languages of Europe. It is unlikely that Boas first arrived on Baffin Island forewarned to watch for velar/uvular distinctions and ergativity. Now more than a century later, an awareness of what distinctions can be significant in languages and what kinds of systems recur can provide tremendous advantages, allowing us to spot potentially important features sooner and identify patterns on the basis of fewer examples.