Practical Perl Linking Compiled Code Into Perl, Java, Or .Net Is Necessary for a by Adam Turoff Minority of Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

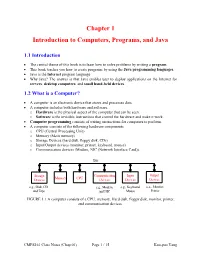

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Some Preliminary Implications of WTO Source Code Proposala INTRODUCTION

Some preliminary implications of WTO source code proposala INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 HOW THIS IS TRIMS+ ....................................................................................................................................... 3 HOW THIS IS TRIPS+ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE TRANSFER OF SOURCE CODE .................................................................. 4 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ........................................................................................................................................... 4 AS A REMEDY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE CONDUCT ............................................................................................................. 4 TAX LAW ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 IN GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ................................................................................................................................ 5 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE ACCESS TO SOURCE CODE ...................................................................... 5 COMPETITION LAW ................................................................................................................................................. -

About ILE C/C++ Compiler Reference

IBM i 7.3 Programming IBM Rational Development Studio for i ILE C/C++ Compiler Reference IBM SC09-4816-07 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 121. This edition applies to IBM® Rational® Development Studio for i (product number 5770-WDS) and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. This version does not run on all reduced instruction set computer (RISC) models nor does it run on CISC models. This document may contain references to Licensed Internal Code. Licensed Internal Code is Machine Code and is licensed to you under the terms of the IBM License Agreement for Machine Code. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1993, 2015. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents ILE C/C++ Compiler Reference............................................................................... 1 What is new for IBM i 7.3.............................................................................................................................3 PDF file for ILE C/C++ Compiler Reference.................................................................................................5 About ILE C/C++ Compiler Reference......................................................................................................... 7 Prerequisite and Related Information.................................................................................................. -

![[PDF] Beginning Raku](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0681/pdf-beginning-raku-210681.webp)

[PDF] Beginning Raku

Beginning Raku Arne Sommer Version 1.00, 22.12.2019 Table of Contents Introduction. 1 The Little Print . 1 Reading Tips . 2 Content . 3 1. About Raku. 5 1.1. Rakudo. 5 1.2. Running Raku in the browser . 6 1.3. REPL. 6 1.4. One Liners . 8 1.5. Running Programs . 9 1.6. Error messages . 9 1.7. use v6. 10 1.8. Documentation . 10 1.9. More Information. 13 1.10. Speed . 13 2. Variables, Operators, Values and Procedures. 15 2.1. Output with say and print . 15 2.2. Variables . 15 2.3. Comments. 17 2.4. Non-destructive operators . 18 2.5. Numerical Operators . 19 2.6. Operator Precedence . 20 2.7. Values . 22 2.8. Variable Names . 24 2.9. constant. 26 2.10. Sigilless variables . 26 2.11. True and False. 27 2.12. // . 29 3. The Type System. 31 3.1. Strong Typing . 31 3.2. ^mro (Method Resolution Order) . 33 3.3. Everything is an Object . 34 3.4. Special Values . 36 3.5. :D (Defined Adverb) . 38 3.6. Type Conversion . 39 3.7. Comparison Operators . 42 4. Control Flow . 47 4.1. Blocks. 47 4.2. Ranges (A Short Introduction). 47 4.3. loop . 48 4.4. for . 49 4.5. Infinite Loops. 53 4.6. while . 53 4.7. until . 54 4.8. repeat while . 55 4.9. repeat until. 55 4.10. Loop Summary . 56 4.11. if . .. -

Compiler Error Messages Considered Unhelpful: the Landscape of Text-Based Programming Error Message Research

Working Group Report ITiCSE-WGR ’19, July 15–17, 2019, Aberdeen, Scotland Uk Compiler Error Messages Considered Unhelpful: The Landscape of Text-Based Programming Error Message Research Brett A. Becker∗ Paul Denny∗ Raymond Pettit∗ University College Dublin University of Auckland University of Virginia Dublin, Ireland Auckland, New Zealand Charlottesville, Virginia, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Durell Bouchard Dennis J. Bouvier Brian Harrington Roanoke College Southern Illinois University Edwardsville University of Toronto Scarborough Roanoke, Virgina, USA Edwardsville, Illinois, USA Scarborough, Ontario, Canada [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Amir Kamil Amey Karkare Chris McDonald University of Michigan Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur University of Western Australia Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Kanpur, India Perth, Australia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Peter-Michael Osera Janice L. Pearce James Prather Grinnell College Berea College Abilene Christian University Grinnell, Iowa, USA Berea, Kentucky, USA Abilene, Texas, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT of evidence supporting each one (historical, anecdotal, and empiri- Diagnostic messages generated by compilers and interpreters such cal). This work can serve as a starting point for those who wish to as syntax error messages have been researched for over half of a conduct research on compiler error messages, runtime errors, and century. Unfortunately, these messages which include error, warn- warnings. We also make the bibtex file of our 300+ reference corpus ing, and run-time messages, present substantial difficulty and could publicly available. -

ROSE Tutorial: a Tool for Building Source-To-Source Translators Draft Tutorial (Version 0.9.11.115)

ROSE Tutorial: A Tool for Building Source-to-Source Translators Draft Tutorial (version 0.9.11.115) Daniel Quinlan, Markus Schordan, Richard Vuduc, Qing Yi Thomas Panas, Chunhua Liao, and Jeremiah J. Willcock Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Livermore, CA 94550 925-423-2668 (office) 925-422-6278 (fax) fdquinlan,panas2,[email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Project Web Page: www.rosecompiler.org UCRL Number for ROSE User Manual: UCRL-SM-210137-DRAFT UCRL Number for ROSE Tutorial: UCRL-SM-210032-DRAFT UCRL Number for ROSE Source Code: UCRL-CODE-155962 ROSE User Manual (pdf) ROSE Tutorial (pdf) ROSE HTML Reference (html only) September 12, 2019 ii September 12, 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is ROSE.....................................1 1.2 Why you should be interested in ROSE.......................2 1.3 Problems that ROSE can address...........................2 1.4 Examples in this ROSE Tutorial...........................3 1.5 ROSE Documentation and Where To Find It.................... 10 1.6 Using the Tutorial................................... 11 1.7 Required Makefile for Tutorial Examples....................... 11 I Working with the ROSE AST 13 2 Identity Translator 15 3 Simple AST Graph Generator 19 4 AST Whole Graph Generator 23 5 Advanced AST Graph Generation 29 6 AST PDF Generator 31 7 Introduction to AST Traversals 35 7.1 Input For Example Traversals............................. 35 7.2 Traversals of the AST Structure............................ 36 7.2.1 Classic Object-Oriented Visitor Pattern for the AST............ 37 7.2.2 Simple Traversal (no attributes)....................... 37 7.2.3 Simple Pre- and Postorder Traversal.................... -

Other Topics 1 Other Topics

Other topics 1 Other topics 1 Other topics 15 Feb 2014 1 1.1 Description 1.1 Description Where to learn more about other topics that are useful for mod_perl developers and users. 1.2 Perl The Perl Documentation http://perldoc.perl.org/ The Perl Home Page http://www.perl.com/ The Perl Monks http://www.perlmonks.org/ What Perl Monks is: Our attempt to make learning Perl as nonintimidating and easy to use as possi- ble. A place for you and others to polish, improve, and showcase your Perl skills. A community which allows everyone to grow and learn from each other. The Perl Journal http://www.tpj.com/ The Perl Review http://theperlreview.com/ The Perl Review is a magazine for the Perl community by the Perl community produced with open source tools. CPAN - Comprehensive Perl Archive Network http://cpan.org and http://search.cpan.org/ Perl Module Mechanics http://world.std.com/~swmcd/steven/perl/module_mechanics.html - This page describes the mechan- ics of creating, compiling, releasing and maintaining Perl modules. Creating (and Maintaining) Perl Modules http://www.mathforum.com/~ken/perl_modules.html XS tutorials 2 15 Feb 2014 Other topics 1.3 Perl/CGI Perl manpages: perlguts, perlxs, and perlxstut manpages. Dean Roehrich’s XS CookBookA and CookBookB http://search.cpan.org/search?dist=CookBookA http://search.cpan.org/search?dist=CookBookB a series of articles by Steven McDougall: http://world.std.com/~swmcd/steven/perl/pm/xs/intro/index.html http://world.std.com/~swmcd/steven/perl/pm/xs/concepts.html http://world.std.com/~swmcd/steven/perl/pm/xs/tools/index.html http://world.std.com/~swmcd/steven/perl/pm/xs/modules/modules.html http://world.std.com/~swmcd/steven/perl/pm/xs/nw/NW.html Advanced Perl Programming By Sriram Srinivasan. -

Basic Compiler Algorithms for Parallel Programs *

Basic Compiler Algorithms for Parallel Programs * Jaejin Lee and David A. Padua Samuel P. Midkiff Department of Computer Science IBM T. J. Watson Research Center University of Illinois P.O.Box 218 Urbana, IL 61801 Yorktown Heights, NY 10598 {j-lee44,padua}@cs.uiuc.edu [email protected] Abstract 1 Introduction Traditional compiler techniques developed for sequential Under the shared memory parallel programming model, all programs do not guarantee the correctness (sequential con- threads in a job can accessa global address space. Communi- sistency) of compiler transformations when applied to par- cation between threads is via reads and writes of shared vari- allel programs. This is because traditional compilers for ables rather than explicit communication operations. Pro- sequential programs do not account for the updates to a cessors may access a shared variable concurrently without shared variable by different threads. We present a con- any fixed ordering of accesses,which leads to data races [5,9] current static single assignment (CSSA) form for parallel and non-deterministic behavior. programs containing cobegin/coend and parallel do con- Data races and synchronization make it impossible to apply structs and post/wait synchronization primitives. Based classical compiler optimization and analysis techniques di- on the CSSA form, we present copy propagation and dead rectly to parallel programs because the classical methods do code elimination techniques. Also, a global value number- not account.for updates to shared variables in threads other ing technique that detects equivalent variables in parallel than the one being analyzed. Classical optimizations may programs is presented. By using global value numbering change the meaning of programs when they are applied to and the CSSA form, we extend classical common subex- shared memory parallel programs [23]. -

A Compiler-Compiler for DSL Embedding

A Compiler-Compiler for DSL Embedding Amir Shaikhha Vojin Jovanovic Christoph Koch EPFL, Switzerland Oracle Labs EPFL, Switzerland {amir.shaikhha}@epfl.ch {vojin.jovanovic}@oracle.com {christoph.koch}@epfl.ch Abstract (EDSLs) [14] in the Scala programming language. DSL devel- In this paper, we present a framework to generate compil- opers define a DSL as a normal library in Scala. This plain ers for embedded domain-specific languages (EDSLs). This Scala implementation can be used for debugging purposes framework provides facilities to automatically generate the without worrying about the performance aspects (handled boilerplate code required for building DSL compilers on top separately by the DSL compiler). of extensible optimizing compilers. We evaluate the practi- Alchemy provides a customizable set of annotations for cality of our framework by demonstrating several use-cases encoding the domain knowledge in the optimizing compila- successfully built with it. tion frameworks. A DSL developer annotates the DSL library, from which Alchemy generates a DSL compiler that is built CCS Concepts • Software and its engineering → Soft- on top of an extensible optimizing compiler. As opposed to ware performance; Compilers; the existing compiler-compilers and language workbenches, Alchemy does not need a new meta-language for defining Keywords Domain-Specific Languages, Compiler-Compiler, a DSL; instead, Alchemy uses the reflection capabilities of Language Embedding Scala to treat the plain Scala code of the DSL library as the language specification. 1 Introduction A compiler expert can customize the behavior of the pre- Everything that happens once can never happen defined set of annotations based on the features provided by again. -

EN-Google Hacks.Pdf

Table of Contents Credits Foreword Preface Chapter 1. Searching Google 1. Setting Preferences 2. Language Tools 3. Anatomy of a Search Result 4. Specialized Vocabularies: Slang and Terminology 5. Getting Around the 10 Word Limit 6. Word Order Matters 7. Repetition Matters 8. Mixing Syntaxes 9. Hacking Google URLs 10. Hacking Google Search Forms 11. Date-Range Searching 12. Understanding and Using Julian Dates 13. Using Full-Word Wildcards 14. inurl: Versus site: 15. Checking Spelling 16. Consulting the Dictionary 17. Consulting the Phonebook 18. Tracking Stocks 19. Google Interface for Translators 20. Searching Article Archives 21. Finding Directories of Information 22. Finding Technical Definitions 23. Finding Weblog Commentary 24. The Google Toolbar 25. The Mozilla Google Toolbar 26. The Quick Search Toolbar 27. GAPIS 28. Googling with Bookmarklets Chapter 2. Google Special Services and Collections 29. Google Directory 30. Google Groups 31. Google Images 32. Google News 33. Google Catalogs 34. Froogle 35. Google Labs Chapter 3. Third-Party Google Services 36. XooMLe: The Google API in Plain Old XML 37. Google by Email 38. Simplifying Google Groups URLs 39. What Does Google Think Of... 40. GooglePeople Chapter 4. Non-API Google Applications 41. Don't Try This at Home 42. Building a Custom Date-Range Search Form 43. Building Google Directory URLs 44. Scraping Google Results 45. Scraping Google AdWords 46. Scraping Google Groups 47. Scraping Google News 48. Scraping Google Catalogs 49. Scraping the Google Phonebook Chapter 5. Introducing the Google Web API 50. Programming the Google Web API with Perl 51. Looping Around the 10-Result Limit 52.