Chapter Two – Corporate Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau Und Bootsbau

Karosseriekonzepte und Fahrzeuginterior KFI INSPIRATIONEN DURCH AERODYNAMIK, FLUGZEUGBAU UND BOOTSBAU Dipl.-Ing. Torsten Kanitz Lehrbeauftragter HAW Hamburg WS 2011-12 15.11.2011 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen durch Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau, Bootsbau 1 „Ein fortschrittliches Auto muss auch fortschrittlich aussehen “ Inspirationen durch Raketenbau / Torpedos 1913, Alfa-Romeo Ricotti Eine Vereinigung von Torpedoform und Eiförmigkeit Formale Aspekte im Vordergrund Bildquelle: /1/ S.157 aus: ALLGEMEINE AUTOMOBIL-ZEITUNG Nr.36, 1919 Ein Bemühen, die damaligen Erkenntnisse aus aerodynamischen Versuchen für den Automobilbau 1899 anzuwenden. Camille Jenatzy Schütte-Lanz SL 20, 1917 „Der rote Teufel“ Zunächst: nur optisch im Jamais Contente (Elektroauto) Die 100 km/h Grenze überschritten Bildquelle: /1/ S.45 Geschwindigkeitsrennen waren an der Tagesordnung aus: LA LOCOMOTION AUTOMOBILE, 1899 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen durch Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau, Bootsbau 2 Inspirationen durch 1906 Raketenbau / Torpedos Daytona Beach „Stanley Rocket “ mit Fred Marriott Geschwindigkeitsweltrekord für Automobile mit Dampfantrieb mit beachtlichen 205,5 km/h Ein Bemühen, die damaligen Erkenntnisse aus aerodynamischen Versuchen für den Automobilbau Elektrotechniker anzuwenden. bedient Schaltungen Zunächst: nur optisch 1902 W.C. Baker Elektromobilfabrik 7-12 PS Elektromotor Torpedoförmiges Fichtenholzgehäuse Bildquelle: /1/ S.63 aus: Zeitschr. d. Mitteleuropäischen Motorwagen-Vereins, 1902 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen -

The Sidelight, February 2020

THE SIDELIGHT Published by KYSWAP, Inc., subsidiary of KYANA Charities 3821 Hunsinger Lane Louisville, KY 40220 February 2020 Printed by: USA PRINTING & PROMOTIONS, 4109 BARDSTOWN ROAD, Ste 101, Louisivlle, KY 40218 KYANA REGION AACA OFFICERS President: Fred Trusty……………………. (502) 292-7008 Vice President: Chester Robertson… (502) 935-6879 Sidelight Email for Articles: Secretary: Mark Kubancik………………. (502) 797-8555 Sandra Joseph Treasurer: Pat Palmer-Ball …………….. (502) 693-3106 [email protected] (502) 558-9431 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Alex Wilkins …………………………………… (615) 430-8027 KYSWAP Swap Meet Business, etc. Roger Stephan………………………………… (502) 640-0115 (502) 619-2916 (502) 619-2917 Brian Hill ………………………………………… (502) 327-9243 [email protected] Brian Koressel ………………………………… (502) 408-9181 KYANA Website CALLING COMMITTEE KYANARegionAACA.com Patsy Basham …………………………………. (502) 593-4009 SICK & VISITATION Patsy Basham …………………………………. (502) 593-4009 THE SIDELIGHT MEMBERSHIP CHAIRMAN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF KYSWAP, Roger Stephan………………………………… (502) 640-0115 INC. LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY HISTORIAN Marilyn Ray …………………………………… (502) 361-7434 Deadline for articles is the 18th of preceding month in order to have it PARADE CHAIRMAN printed in the following issue. Articles Howard Hardin …………………………….. (502) 425-0299 from the membership are welcome and will be printed as space permits. CLUB HOUSE RENTALS Members may advertise at no charge, Ruth Hill ………………………………………… (502) 640-8510 either for items for sale or requests to obtain. WEB MASTER Editorials and/or letters to the editor Interon Design …………………………………(502) 593-7407 are the personal opinion of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the CHAPLAIN official policy of the club. Ray Hayes ………………………………………… (502) 533-7330 LIBRARIAN Jane Burke …………………………………….. (502) 500-8012 From the President Fred Trusty Last month I reported that we lost 17 members in 2019 for various reasons. -

Download Chapter 119KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 128 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 129 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 1910–1996 WRITTEN BY JAMES W. FURLONG SUBMITTED BY THE NAE HOME SECRETARY GEORGE J. HUEBNER, JR., one of the foremost engineers in the field of automotive research, was especially noted for developing the first practical gas turbine for a passenger car. He died of pulmonary edema in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on September 4, 1996. George earned a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan in 1932. He began work in the mechanical engineering laboratories at Chrysler Corporation in 1931 and completed his studies on a part- time basis. He was promoted to assistant chief engineer of the Plymouth Division in 1936 and returned to the Central Engineering Division in 1939 to work with Carl Breer, one of the three engineers who had designed the first Chrysler vehicle fifteen years earlier. George was especially pleased to work for Breer, whom he regarded as one of the most capable engineers in the country. Breer established a research office in 1939 and named George as his assistant. It became evident to George that he should bring more science into the field. When he became chief engineer in 1946, he enlarged the activities of Chrysler Research into the fields of physics, metallurgy, and chemistry. He was early to use the electron microscope. George also was early to see the need for digital computers in automotive engineering. Largely in recognition of this pioneering work, he was awarded the Buckendale Prize for computer- Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Tj 'WMYAITO-Fiwgraphy

46 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS, OCTOBER 14, 1940 thought of the high command, had dug up the capital to launch the lobby 0f tuT Commodore, then the enterprise, Joe Fields, who knew practically crJ? * and veteran of the automobile show every worth-while dealer in the country, had, as vice- several big Tj manufacturers h 'WMYAITO-fiWGRAPHY the plays as well as 1 saga president and general sales manager, guaranteed being i n thai 4l|ft| TOE of the first retail outlets so necessary to launching this new product. itself. Joe suggested the 100 YEARS CN dore and Walter P. toM RUBEER All bases had been covered and the new automobile hire the lobby, adding, “w,Su was industry. So when a show all right.” set to blitzkrieg the automobile And J OV* the Studebaker deal was abruptly terminated, Chrysler vanishing act—a short oneZJr same ing with the right name was set to go. His plans were so perfected that the dotted line of the off he gave the go-ahead necessary day negotiations were broken ment which permitted him f to the late Theodore F. MacManus, who already had the boss: "We own the Chapter XCII—The Probably it ”b£' Chrysler Corp. written his advertising copy. The baby had been born. was just as Mark Twain created advertising broadside Chrysler had to show Pudd’nhead Wilson half a century Well I remember the stir this outside * ago and made him created, boldness way, for the Commodore lobhv as famous as A. Conan Doyle did his of the newcomer in the industry the as good as a ringside bherlock Holmes. -

Car Owner's Manual Collection

Car Owner’s Manual Collection Business, Science, and Technology Department Enoch Pratt Free Library Central Library/State Library Resource Center 400 Cathedral St. Baltimore, MD 21201 (410) 396-5317 The following pages list the collection of old car owner’s manuals kept in the Business, Science, and Technology Department. While the manuals cover the years 1913-1986, the bulk of the collection represents cars from the 1920s, ‘30s, and 40s. If you are interested in looking at these manuals, please ask a librarian in the Department or e-mail us. The manuals are noncirculating, but we can make copies of specific parts for you. Auburn……………………………………………………………..……………………..2 Buick………………………………………………………………..…………………….2 Cadillac…………………………………………………………………..……………….3 Chandler………………………………………………………………….…...………....5 Chevrolet……………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chrysler…………………………………………………………………………….…….7 DeSoto…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Diamond T……………………………………………………………………………….8 Dodge…………………………………………………………………………………….8 Ford………………………………………………………………………………….……9 Franklin………………………………………………………………………………….11 Graham……………………………………………………………………………..…..12 GM………………………………………………………………………………………13 Hudson………………………………………………………………………..………..13 Hupmobile…………………………………………………………………..………….17 Jordan………………………………………………………………………………..…17 LaSalle………………………………………………………………………..………...18 Nash……………………………………………………………………………..……...19 Oldsmobile……………………………………………………………………..……….21 Pontiac……………………………………………………………………….…………25 Packard………………………………………………………………….……………...30 Pak-Age-Car…………………………………………………………………………...30 -

Paycheck Protection Program Loans

Paycheck Protection Program Loans Loan Amount Business Name Headquarters City a $5-10 million ABO LEASING CORPORATION PLYMOUTH a $5-10 million ACMS GROUP INC CROWN POINT a $5-10 million ALBANESE CONFECTIONERY GROUP, INC. MERRILLVILLE a $5-10 million AMERICAN LICORICE COMPANY LA PORTE a $5-10 million AMERICAN STRUCTUREPOINT, INC. INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million ASH BROKERAGE, LLC FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million ASHLEY INDUSTRIAL MOLDING, INC. ASHLEY a $5-10 million BEST CHAIRS INCORPARATED FERDINAND a $5-10 million BIOANALYTICAL SYSTEMS, INC. WEST LAFAYETTE a $5-10 million BLUE & CO LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million BLUE HORSESHOE SOLUTIONS INC. CARMEL a $5-10 million BRAVOTAMPA, LLC MISHAWAKA a $5-10 million BRC RUBBER & PLASTICS INC FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million BTD MANUFACTURING INC BATESVILLE a $5-10 million BUCKINGHAM MANAGEMENT, L.L.C. INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million BYRIDER SALES OF INDIANA S LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million C.A. ADVANCED INC WAKARUSA a $5-10 million CFA INC. BATESVILLE a $5-10 million CINTEMP INC. BATESVILLE a $5-10 million CONSOLIDATED FABRICATION AND CONSTRUCTORS INC GARY a $5-10 million COUNTRYMARK REFINING & LOGISTICS LLC MOUNT VERNON a $5-10 million CROWN CORR, INC. GARY a $5-10 million CUNNINGHAM RESTAURANT GROUP LLC INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million DECATUR COUNTY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL GREENSBURG a $5-10 million DIVERSE STAFFING SERVICES, INC. INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million DRAPER, INC. SPICELAND a $5-10 million DUCHARME, MCMILLEN & ASSOCIATES, INC. FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million ELECTRIC PLUS, INC AVON a $5-10 million ENVIGO RMS, LLC INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million ENVISTA, LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million FLANDERS ELECTRIC MOTOR SERVICE INC EVANSVILLE a $5-10 million FOX CONTRACTORS CORP FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million FUSION ALLIANCE, LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million G.W. -

2015 Annual Report

2015 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ABOUT THE ALLIANCE This organization focuses on developing economic prosperity for our community by achieving goals and executing programs that benefit Kokomo and Howard County’s residents, businesses, organizations, and visitors. Together, the Alliance’s vision, mission, and values guide our strategic plan and define the ways in which we execute to accomplish the goals within each organizational priority. OUR VISION The vision of the Greater Kokomo Economic Development Alliance seeks to foster economic prosperity for Kokomo and Howard County through new investment, population growth, and the continued success of our area’s current businesses and residents. OUR MISSION The Greater Kokomo Economic Development Alliance aligns, links, and leverages resources to build community prosperity. OUR VALUES We are guided to act and driven to succeed by four sets of values: ∞ Integrity and Respect ∞ Inclusiveness ∞ Efficiency and Effectiveness ∞ Continuous Improvement OUR STRATEGIC PRIORITIES Our goals and actions align with five strategic priorities: ∞ Leadership and Collaboration ∞ Economic Vitality ∞ Talent Attraction ∞ Innovation and Entrepreneurship ∞ Quality Places ANNUAL REPORT: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT KEY ACCOMPLISHMENTS In partnership with local government, the Alliance helped facilitate the attraction of a new primary employer in 2015, Indiana manufacturer Saran Industries, and saw the expansion of local manufacturer METCO, Inc. 2015 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS DESCRIPTION DATE INVESTMENT JOBS ESTIMATE METCO, Inc. 8/2015 $500,000 10 Saran Industries 9/2015 $4.4 million 60 Total 2015 investment $4.9 million 70 ABOUT SARAN INDUSTRIES Headquartered in Indianapolis, Saran Industries provides surface finishing of metal products for the automotive industry. Due to the nature of its operations and close proximity to key clients, Kokomo’s location and skilled workforce made it an ideal location for the company. -

Digital Magazine #7

DIGITAL MAGAZINE 7 Jeep, the Jeep grille and related logos, vehicle model names and trade dress are trademarks of FCA US LLC and used under license by Premium & Collectibles Trading Co ltd. ©2021 FCA US LLC. CONTENTS THE JEEP® STORY 1 THE FIRST ORDER THE JEEP® Brand 6 THE SUCCESS OF THE CJ-5 © 2021 YOUR COLLECTION Editorial Manager: Phil Hunt Eaglemoss Inc. Build the WIllys MB Jeep® Design Manager: Caroline Grimshaw 315 West 36th Street is available by monthly subscription. New York, NY 10018 www.build-willysjeep.com Packaged by: Milanoedit srl, www.milanoedit.com Eaglemoss Ltd., US CUSTOMER SERVICE Premier Place, For questions about the collection, Researcher/writer: Roberto Bruciamonti 2 & A Half Devonshire Square, replacements and substitutions, London, EC2M 4UJ, UK or to cancel, pause or modify Photography credits: © NARA (pp.1, 2, 3, 4), your subscription, please call © Bruciamonti (p.5), 144 Avenue Charles de Gaulle, our US Customer Service team © FCA (p.6, 7, 8, 9) 92200 NEUILLY-SUR-SEINE, at 800-261-6898, or email us at France [email protected] Die-Cast Club® 2021 All rights reserved Jeep, the Jeep grille and related logos, vehicle model names and trade dress are trademarks of FCA US LLC and used under license by Premium & Collectibles Trading Co ltd. ©2021 FCA US LLC. THE JEEP® STORY THE FIRST ORDER THE FIRST ORDER ▲ A formation of Willys MAs parade The first pre-series vehicles were delivered along San Francisco Bay in front of the Golden Gate Bridge, opened despite a number of initial problems. just a few years before. -

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019 The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | Friday April 26 and Saturday April 27, 2019 10am BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS 580 Madison Avenue Rupert Banner +1 (212) 644 9001 New York, New York 10022 +1 (917) 340 9652 +1 (212) 644 9009 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90046 Evan Ide From April 23 to 29, to reach us at +1 (917) 340 4657 the Tupelo Automobile Museum: 220 San Bruno Avenue [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6514 San Francisco, California 94103 +1 (212) 644 9009 John Neville +1 (917) 206 1625 bonhams.com/tupelo To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] bonhams.com/tupelo PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION Eric Minoff The Tupelo Automobile Museum +1 (917) 206-1630 Please see pages 4 to 5 and 223 to 225 for 1 Otis Boulevard [email protected] bidder information including Conditions Tupelo, Mississippi 38804 of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Automobilia PREVIEW Toby Wilson AUTOMATED RESULTS SERVICE Thursday April 25 9am - 5pm +44 (0) 8700 273 619 +1 (800) 223 2854 Friday April 26 [email protected] Automobilia 9am - 10am FRONT COVER Motorcars 9am - 6pm General Information Lot 450 Saturday April 27 Gregory Coe Motorcars 9am - 10am +1 (212) 461 6514 BACK COVER [email protected] Lot 465 AUCTION TIMES Friday April 26 Automobilia 10am Gordan Mandich +1 (323) 436 5412 Saturday April 27 Motorcars 10am [email protected] 25593 AUCTION NUMBER: Vehicle Documents Automobilia Lots 1 – 331 Stanley Tam Motorcars Lots 401 – 573 +1 (415) 503 3322 +1 (415) 391 4040 Fax ADMISSION TO PREVIEW AND AUCTION [email protected] Bonhams’ admission fees are listed in the Buyer information section of this catalog on pages 4 and 5. -

The Forgotten Father Free

FREE THE FORGOTTEN FATHER PDF Thomas A Smail | none | 01 Jul 2001 | Wipf & Stock Publishers | 9781579105426 | English | Eugene, United States The forgotten father | endeavors His name graces not a single vehicle from Ford, Chrysler, or General Motors, but if one person can be said to have started the domestic American automobile industry, a strong The Forgotten Father could be made for Benjamin Briscoe. He provided the startup funds for the original car companies that, in time, became the basis for two of the Big Three The Forgotten Father, and he almost took control of the third. His father started a successful company, Michigan Nut and Bolt, that produced fasteners for equipment using a machine of his own design. He then sold that business to the American Can Company The Forgotten Father he could form a new enterprise, Detroit Galvanizing and Sheet Metal Works, to exploit a machine he had The Forgotten Father for making corrugated pipe. His product range soon expanded to include sheet-metal parts for stoves and ranges. Two years later, Briscoe was approached by Ransom E. Olds to manufacture an improved cooling system for the original curved-dash Oldsmobile. Briscoe agreed to make radiators, but a year earlier his firm had its own crisis of survival. In desperate need of operating capital and able The Forgotten Father to find a small loan locally, Ben Briscoe took a train to New York City. Not only did Briscoe brashly talk his way into a meeting with financiers at J. That funding allowed his company to make radiators, fenders, and gas tanks for Oldsmobile, and also established a relationship with the Morgan firm that would help Briscoe in his automotive ventures. -

Complete Studebaker Manual 1929-Part1

OWNER'S MANUAL Studebaker President Eight 131 and 121-inch Wheelbase Models THE STUDEBAKER CORPORATION OF AMERICA sotJT1-IBEND, INDIANA, LICENSE DATA Number of cylinders Cylinder Bore 3% inches Stroke inchqs Piston Displacement 336 cubic inches Horse power (N. A. C. C. Rating) Wheelbase 131 and 21 inches Engine Number—On top surface of fan bracket boss. Serial Number—on plate riveted to frame under left front fender. Body Number-—On plate attached to front of dash under hood. on the weight of any model can be ob- tained from the dealer. The Use of This Book For the convenience of the owner we have divided the book into three sections, "Operation," "Care" and "Adjustments." The first section, starting on page 5, contains driving sug- gestions and information on the instruments and controls. This section of the book is of great importanceand should be thoroughly read by every owner no matter how experi- enced a motorist he may be. The second section, starting on page 16, carries instructions on the lubrication and care of the car, including many details which will be of interest to every owner. The third section, starting on page 35, covers in detail a number of adjustment operations. To the car owner who desires to take advantage of the facilities of a Studebaker- Erskine Service Station, this section may not appeal and it need not be read unless desired. The book should always be kept in the car, however, as this section may prove of value, if at any time when touring, it is necessaryto go to a garage not familiar with the car. -

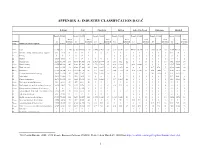

Appendix A: Industry Classification Data1

APPENDIX A: INDUSTRY CLASSIFICATION DATA1 Beltrami Clay Clearwater Kittson Lake of the Woods Mahnomen Marshall Payroll ($1,000) Payroll ($1,000) Payroll ($1,000) Payroll ($1,000) Payroll ($1,000) Payroll ($1,000) Payroll ($1,000) Total Total Total Total Total Total Total Industry 1st Establish- 1st Establish- 1st Establish- 1st Establish- 1st Establish- 1st Establish- 1st Establish- Code Industry Code Description Quarter Annual ments Quarter Annual ments Quarter Annual ments Quarter Annual ments Quarter Annual ments Quarter Annual ments Quarter Annual ments ------ Total 75,948 326,715 1,142 67,807 288,022 1,161 11,448 58,412 208 5,189 21,543 163 44,682 156,847 155 3,605 16,334 115 8,564 43,626 277 11---- Forestry, fishing, hunting, and ag. support 598 1,875 21 0 0 6 0 0 6 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 2 151 774 9 21---- Mining 0 0 2 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 22---- Utilities 1,310 5,061 4 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 23---- Construction 5,268 31,778 150 7,898 37,568 141 3,303 23,777 33 109 502 12 0 0 14 0 0 10 632 7,337 37 31---- Manufacturing 11,474 46,183 46 6,920 27,108 41 3,751 15,690 16 298 1,223 7 2601 10,240 11 0 0 2 1,707 7,662 15 42---- Wholesale trade 3,093 13,505 53 4,503 17,106 65 220 1,007 9 859 3,251 18 0 0 9 137 678 5 1526 6,448 28 44---- Retail trade 13,168 54,844 218 10,517 45,736 187 871 3,669 37 804 3,333 34 620 2,543 28 696 3,046 27 1161 5,959 43 48---- Transportation & warehousing 2,689 11,650 44 1,699 7,043 60 328 1,526 15 0 0 5 0 0 5 294 1415 9 152 1514 12 51---- Information 3,033 12,866 22 550 1,839 12 0 0 2 0 0 3