Martin Buber: Philosopher of Dialogue and of the Resolution of Conflict 11 Professor W John Morgan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Väsen I Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan

Väsen i Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan Sjöberg Översättning: Redigering: Chronopia: Bill King, Michael Stenmark, Nils Gulliksson, Henrik Strandberg Formgivning: Original: Marcus Thorell Omslag: Adrian Smith Grafisk Form: Illustrationer: Adrian Smith, Alvaro Tapia Koncept: Stefan Ljungqvist, Johan Sjöberg Kartor: Övriga Bidrag: Filip Alexanderson, Hanners Kristoferson, Fredrik Malmberg, Henrik Strandberg, Nils Gulliksson, Sami Sinerva, Jonas Mases, Patric Backlund, Cees Kwadijk Baksida: Paolo Parente Projektledning: Stefan Ljungqvist So you want to learn something about the chronopian people? Forsa the sabranska mysteries, get to know the secrets that made brundusierna so rich, understand marajiputternas brutal fanaticism and unconditional surrender to the black tobacco, nattländarnas desperate escape and ice barbarians worship of Snow Witch. Then I have the book for you my friend. Just look up Melkastors "The chronopian peoples", which delivers the wise man and adventurer all the wisdom you need. If he is still alive? No. When the book arrived, he was executed for blasphemy by the emperor. Read - and maybe you will understand why. Human ethnicities During my many long and intense years as a guest in the brutal, multifaceted and legendary chronopian reality, I had the dubious pleasure to encounter the most varied gallery of the known world has to offer, bump into high and low, exchange experiences with sabranska desert knights, brundusiska trade princes and blue skinned isbarbarer with frosty mustache. I have engaged in telepathy with charibiska hexbarons, given boozed Red Corsairs on the nut, fled howling marajiputtiska fanatics and young and inexperienced taken refuge in faltrakiernas false bosom and sold as a slave to the salt mines. -

HBO, Sky's 'Chernobyl' Leads 2020 Baftas with 14 Nominations

HBO, Sky's 'Chernobyl' Leads 2020 BAFTAs with 14 Nominations 06.04.2020 HBO and Sky's Emmy-winning limited series Chernobyl tied Killing Eve's record, set last year, of 14 nominations at the 2020 BAFTA TV awards. That haul helped Sky earn a total of 25 nominations. The BBC led with a total of 79, followed by Channel 4 with 31. The series about the nuclear disaster that befell the Russian city was nominated best mini-series, with Jared Harris and Stellan Skarsgård nommed best lead and supporting actor, respectively. Other limited series to score nominations were ITV's Confession, BBC One's The Victim and Channel 4's The Virtues. Netflix's The Crown, produced by Left Bank Pictures, was next with seven total nominations, including best drama and acting nominations for Oscar-winner Olivia Colman, who played Queen Elizabeth, and Helena Bonham Carter, who played Princess Margaret. Also nominated best drama were Channel 4 and Netflix's The End of the F***ig World, HBO and BBC One's Gentleman Jack and BBC Two's Giri/Haji. Besides Colman, dramatic acting nominations went to Glenda Jackson for BBC One's Elizabeth Is Missing, Emmy winner and last year's BAFTA winner Jodie Comer for BBC One's Killing Eve, Samantha Morton for Channel 4's I Am Kirsty and Suranne Jones for Gentleman Jack. Besides Harris, men nominated for lead actor include Callum Turner for BBC One's The Capture, Stephen Graham for The Virtues and Takehiro Hira for Giri/Haji. And besides Carter, other supporting actress nominations went to Helen Behan for The Virtues, Jasmine Jobson for Top Boy and Naomi Ackie for The End of the F***ing World. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem

ENTERTAINMENT ‘Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem By Ericka Blount Danois on September 9, 2013 “One looks down in secret and sees many things,” Dr. Valentin Narcisse (Jeffrey Wright) deadpans, speaking to Chalky White (Michael K. Williams). “You know what I saw? A servant trying to be a king.” And so begins a dance of power, politics and personality between two of the most electrifying, enigmatic actors on the television screen today. Each time the two are on screen—together or apart—they breathed new life into tonight’s premiere episode of Boardwalk Empire season four, with dark humor, slight smiles, powerful glances, smart clothes and killer lines. Entitled “New York Sour,” the episode opened with bombast, unlike the slow boil of previous seasons. Set in 1924, we’re introduced to the tasteful opulence of Chalky White’s new club, The Onyx, decorated with sconces custom-made in Paris and shimmering, shapely dancing girls. Chalky earned an ally, and eventually a partnership to be able to open the club, with former political boss and gangster Nucky Thompson (Steve Buscemi) by saving Nucky’s life last season. This sister club to the legendary Cotton Club in Harlem is Whites-only, but features Black acts. There are some cringe-worthy moments when Chalky, normally proud and infallible, has to deal with racism and bends over to appease his White clientele. But more often, Chalky—a Texas- born force to be reckoned with—breathes an insistent dose of much needed humor into what sometimes devolves into cheap shoot ’em up thrills this season. The meeting of the minds between Narcisse and Chalky takes root in the aftermath of a mistake by Chalky’s right hand man, Dunn Purnsley (Erik LaRay Harvey), who engages in an illicit interracial tryst that turns out to be a dramatic, racially-charged sex game gone horribly wrong. -

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage Phoebe S. Spinrad Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright© 1987 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. A shorter version of chapter 4 appeared, along with part of chapter 2, as "The Last Temptation of Everyman, in Philological Quarterly 64 (1985): 185-94. Chapter 8 originally appeared as "Measure for Measure and the Art of Not Dying," in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 26 (1984): 74-93. Parts of Chapter 9 are adapted from m y "Coping with Uncertainty in The Duchess of Malfi," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 6 (1980): 47-63. A shorter version of chapter 10 appeared as "Memento Mockery: Some Skulls on the Renaissance Stage," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 10 (1984): 1-11. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spinrad, Phoebe S. The summons of death on the medieval and Renaissance English stage. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English drama—Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1700—History and criticism. 2. English drama— To 1500—History and criticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Death- History. I. Title. PR658.D4S64 1987 822'.009'354 87-5487 ISBN 0-8142-0443-0 To Karl Snyder and Marjorie Lewis without who m none of this would have been Contents Preface ix I Death Takes a Grisly Shape Medieval and Renaissance Iconography 1 II Answering the Summon s The Art of Dying 27 III Death Takes to the Stage The Mystery Cycles and Early Moralities 50 IV Death -

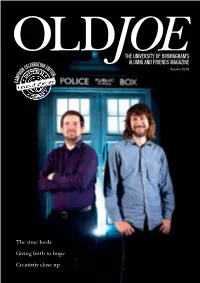

Old Joe Autumn 2015

OLDJOETHE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM’S ALUMNI AND FRIENDS MAGAZINE Autumn 2015 The time lords Giving birth to hope Creativity close up 2 OLD JOE THE FIRST WORD The firstword This special edition of Old Joe magazine celebrates something truly extraordinary; GUEST EDITOR the University’s pioneering Circles of Influence fundraising campaign raising Each year Birmingham has many an astounding £193,426,877.47 million. reasons to celebrate, and this year Circles of Influence substantially has been no different. The Circles exceeded its £160 million target to of Influence campaign has officially become the largest charitable campaign raised £193.4 million, funding outside Oxford, London, and Cambridge, extraordinary projects on campus, and this was only possible through the locally and globally (page 8). kindness and generosity of our donors I am honoured to represent the and volunteers. University by graduating as its From completing the Aston Webb semi-circle with the Bramall Music Building symbolic 300,000th alumna (page to funding life-saving cancer research, the campaign has left a wonderful legacy 36). Being part of this momentous to the University and the impact of donors’ gifts will be felt for years to come. From occasion has been a fantastic way to our very conception as England’s first civic university more than a century ago, end my three years as an Birmingham has been founded through philanthropy and our donors’ generosity is undergraduate. I have thoroughly keeping that vision strong. enjoyed my time here. Inside this magazine, you can read how our extraordinary campaign has changed During my final year I was treasurer thousands of people’s lives, and learn more about some of the exciting new areas of the Women in Finance society, so addressing society’s biggest challenges where our fundraising will now focus, it was inspiring to read alumna Billie from saving mothers’ lives in Africa to innovative new cancer treatments. -

Cairncross Review a Sustainable Future for Journalism

THE CAIRNCROSS REVIEW A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE FOR JOURNALISM 12 TH FEBRUARY 2019 Contents Executive Summary 5 Chapter 1 – Why should we care about the future of journalism? 14 Introduction 14 1.1 What kinds of journalism matter most? 16 1.2 The wider landscape of news provision 17 1.3 Investigative journalism 18 1.4 Reporting on democracy 21 Chapter 2 – The changing market for news 24 Introduction 24 2.1 Readers have moved online, and print has declined 25 2.2 Online news distribution has changed the ways people consume news 27 2.3 What could be done? 34 Chapter 3 – News publishers’ response to the shift online and falling revenues 39 Introduction 39 3.1 The pursuit of digital advertising revenue 40 Case Study: A Contemporary Newsroom 43 3.2 Direct payment by consumers 48 3.3 What could be done 53 Chapter 4 – The role of the online platforms in the markets for news and advertising 57 Introduction 57 4.1 The online advertising market 58 4.2 The distribution of news publishers’ content online 65 4.3 What could be done? 72 Cairncross Review | 2 Chapter 5 – A future for public interest news 76 5.1 The digital transition has undermined the provision of public-interest journalism 77 5.2 What are publishers already doing to sustain the provision of public-interest news? 78 5.3 The challenges to public-interest journalism are most acute at the local level 79 5.4 What could be done? 82 Conclusion 88 Chapter 6 – What should be done? 90 Endnotes 103 Appendix A: Terms of Reference 114 Appendix B: Advisory Panel 116 Appendix C: Review Methodology 120 Appendix D: List of organisations met during the Review 121 Appendix E: Review Glossary 123 Appendix F: Summary of the Call for Evidence 128 Introduction 128 Appendix G: Acknowledgements 157 Cairncross Review | 3 Executive Summary Executive Summary “The full importance of an epoch-making idea is But the evidence also showed the difficulties with often not perceived in the generation in which it recommending general measures to support is made.. -

Chapter 2 Yeardley's Fort (44Pg65)

CHAPTER 2 YEARDLEY'S FORT (44PG65) INTRODUCTION In this chapter the fort and administrative center of Flowerdew at 44PG65 are examined in relation to town and fortification planning and the cultural behavior so displayed (Barka 1975, Brain et al. 1976, Carson et al. 1981; Barka 1993; Hodges 1987, 1992a, 1992b, 1993; Deetz 1993). To develop this information, we present the historical data pertaining to town development and documented fortification initiatives as a key part of an overall descriptive grid to exploit the ambiguity of the site phenomena and the historic record. We are not just using historic documents to perform a validation of archaeological hypotheses; rather, we are trying to understand how small-scale variant planning models evolved regionally in a trajectory away from mainstream planning ideals (Beaudry 1988:1). This helps refine our perceptions of this site. The analysis then turns to close examination of design components at the archaeological site that might reveal evidence of competence or "mental template." These are then also factored into a more balanced and meaningful cultural interpretation of the site. 58 59 The site is used to develop baseline explanatory models that are considered in a broader, multi-site context in Chapter 3. Therefore, this section will detail more robust working interpretations that help lay the foundations for the direction of the entire study. In short, learning more about this site as a representative example of an Anglo-Dutch fort/English farmstead teaches us more about many sites struggling with the same practical constraints and planning ideals that Garvan (1951) and Reps (1972) defined. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

Native American Literature Symposium

THE NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE SYMPOSIUM Indians in Unexpected Places March 22 - 24, 2018 Mystic Lake Hotel & Casino - Prior Lake, Minnesota The Native American Literature Symposium is organized by an independent group of Indigenous scholars committed to making a place where Native voices can be heard. Since 2001, we have brought together some of the most influential voices in Native America to share our stories—in art, prose, poetry, film, religion, history, politics, music, philosophy, and science—from our worldview. Gwen N. Westerman, Director Minnesota State University, Mankato Gordon Henry, Jr., Publications Editor Michigan State University LeAnne Howe, Arts Liaison University of Georgia Virginia Carney, Tribal College Liaison President Emeritus, Leech Lake Tribal College Denise Cummings, Film Wrangler Rollins College Theo Van Alst, Film Wrangler University of Montana Margaret Noodin, Awards University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Tyler Barton, Assistant to the Director Minnesota State University, Mankato Tria Wakpa Blue, Vendor/Press Coordinator University of California, Berkeley Fantasia Painter, Vendor/Press Assistant University of California, Berkeley Web: www.nativelit.com Facebook: Native American Literature Symposium Twitter: @NALSymposium Prior Lake, Minnesota Wopida, Miigwech, Mvto, Wado, Ahe’ee, Yakoke We thank the sponsors of the 2018 Symposium for their generous funding and continued support that made everything possible. Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (SMSC) Charlie Vig, Tribal Chairman Deborah Peterson, Donation Coordinator