CA98 Attheraces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Primrose Drive, Ripon, North Yorkshire, HG4 1EY Guide Price £420,000

11 Primrose Drive, Ripon, North Yorkshire, HG4 1EY Guide price £420,000 www.joplings.com We are delighted to offer to market a Five Bedroom Detached family home with versatile, extended living accommodation, situated in a quiet cul-de-sac in the popular Palace Road area of Ripon. The property benefits from Gardens to all sides and a Double Garage with Driveway Parking. www.joplings.com DIRECTIONS flooring. Contemporary vertical wall-mounted radiator. Cupboard OUTSIDE From our Ripon Office on North Street, head North to the Victoria Clock housing the Vaillant gas combi boiler. Recessed lighting. Tower traffic lights. Turn left into Palace Road (A6108) and take the first turning on the left hand side into Primrose Drive. Follow the road round CONSERVATORY TO THE FRONT to the left and the property will be found on the left hand side. UPVC Conservatory with doorway leading out to the Patio seating area. Walled front boundary with hedging and shrubs. Pedestrian access gate Tiled flooring with underfloor heating. and pathway leads to the Front Entrance door. Garden mainly laid to ADDITIONAL SITUATIONAL INFORMATION lawn. Steps lead down to a trellis archway leading around to the Rear Ripon is the third smallest city in England and is known for the imposing UTILITY ROOM Garden. Cathedral, Ripon Racecourse and the nearby, Fountains Abbey and UPVC part-glazed door leading out to the Rear of the property with a Studley Royal Gardens. Ripon Market Place is at the centre of the City further window to the side. Deep Belfast Sink. Space and plumbing for GARAGE with a variety of local shops and amenities within easy walking distance. -

Please Click Here for Racecourse Contact Details

The Racing Calendar COPYRIGHT UPDATED: MONDAY, JUNE 14TH, 2021 RACECOURSE INFORMATION Owners may purchase additional badges and these badges AINTREE ASCOT may be purchased at the main entrance and will admit partnership or syndicate members to the owners’ and trainers’ facilities only on the day that their horse is running. Numbers of additional badges must be agreed in advance. PASS is operational at all fixtures EXCLUDING Clerk of the Course Miss Sulekha Varma Clerk of the Course C. G. Stickels, Esq. ROYAL ASCOT. Tel: (0151) 523 2600 Tel: Ascot (01344) 878502 Enquiries to PASS helpline Tel: (01933) 270333 Mob: (07715) 640525 Fax: Ascot (0870) 460 1250 Fax: (0151) 522 2920 Email: [email protected] Car Parking Email: [email protected] Ascot Racecourse, Ascot, Berkshire, SL5 7JX Owners are entitled to free car parking accommodation Chairman Nicholas Wrigley Esq. Chief Executive G. Henderson, Esq. in the owners car park, situated in Car Park No. 2, on the North West Regional Director Dickon White Medical Officers Dr R. Goulds, M.B., B.S., day that their horse is declared to run. No more than two Veterinary Surgeons J. Burgess, T. J. Briggs, Dr R. McKenzie, M.B., B.S., spaces are allocated for each horse. The car park is A. J. M. Topp, Prof. C. J. Proudman, Dr E. Singer, Dr J. Heathcock, B.Sc., M.B, Ch.B, Dr J. Sadler M.B., B.S., situated on the A329, three hundred yards from the K. Summer, J. Tipp, S. Taylor, P. MacAndrew, K. Comb Dr D. Smith M.B., B.S., Dr J. -

Ure Corridor Recreation Area

A The Marina. AREA 75 Approved UreUre CorridorCorridor recreationrecreation areaarea Feb 2004 (Ripon(Ripon ToTo NewbyNewby Reach)Reach) Description This is an area of intensive recreational use situated along the eastern edge of Ripon and covering almost 4km² of the Ripon Canal and River Ure corridor. The two water courses run almost parallel to each other in a north-south direction through the area to the point where they meet approximately one mile upstream of Newby Hall. The watercourses are well-wooded providing an intimate and attractive setting for boaters and walkers with dispersed views into the landscape beyond. A strong network of public footpaths provides easy access to the banks of the canal and much of the riverbank and is a valuable resource to the local community. Beyond the watercourses, the flat landscape is more open and management is a mixture of wild looking wetland with outgrown hedges and unkempt vege tation that contrast with the manicured appearance of the marina, sailing club and racecourse. Built form and boundary treatments display a variety of styles and modern materials that lack cohesion giving a somewhat chaotic appearance to this pleasant area. Key Characteristics Geology, soils and drainage Magnesian limestone solid geology overlain with alluvial drift geology. ©Crown Copyright. All Rights Reserved. Deep, stoneless, permeable, coarse loamy Harrogate Borough Council. 1000 19628 2004. brown soils and slowly-permeable, seasonally- waterlogged, clayey and fine, loamy over HARROGATE DISTRICT Location in Harrogate District Landscape Character Assessment clayey surface water gley soils. Landform and drainage pattern Area boundary* Not to Flat landform below 20m AOD Camera location Scale & direction The River Ure and associated tributaries along with Ripon Canal are the dominant NB Due to the nature of landform, surface treatment and soil/geology composition Character watercourses. -

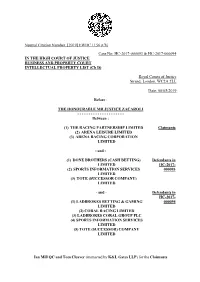

High Court Judgment Template

Neutral Citation Number: [2019] EWHC 1156 (Ch) Case No: HC-2017-000093 & HC-2017-000094 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURT INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (Ch D) Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 08/05/2019 Before : THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : (1) THE RACING PARTNERSHIP LIMITED Claimants (2) ARENA LEISURE LIMITED (3) ARENA RACING CORPORATION LIMITED - and - (1) DONE BROTHERS (CASH BETTING) Defendants in LIMITED HC-2017- (2) SPORTS INFORMATION SERVICES 000093 LIMITED (3) TOTE (SUCCESSOR COMPANY) LIMITED - and - Defendants in HC-2017- (1) LADBROKES BETTING & GAMING 000094 LIMITED (2) CORAL RACING LIMITED (3) LADBROKES CORAL GROUP PLC (4) SPORTS INFORMATION SERVICES LIMITED (5) TOTE (SUCCESSOR) COMPANY LIMITED Ian Mill QC and Tom Cleaver (instructed by K&L Gates LLP) for the Claimants Michael Bloch QC and Craig Morrison (instructed by CMS Cameron McKenna Nabarro Olswang LLP) for the Second Defendant (in HC-2017-000093) and Fourth Defendant (in HC-2017-000094) Hearing dates: 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 31 January 2019 & 1 February 2019 Post-trial written submissions 8 March 2019 & 15 March 2019 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ............................. MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI MR JUSTICE ZACAROLI Racing Partnership v Ladbrokes Et al Approved Judgment A. Introduction 1 B. The horseracing data in issue 7 (i) Betting Prices 8 (ii) Raceday Data 13 (iii) The commercial value of Betting Shows and Raceday Data 14 C. -

Welcome Pack

Welcome to St George’s Court We wish you a pleasant stay and hope you find the following pages of information useful. If you would prefer fresh milk rather than the milk portions, please ask at the house If you require any extra pillows, please just ask. You will find spare blankets in each room in case you require them. You will also find situated in a drawer a hairdryer a radio alarm clock and rechargeable torch. If you require the use of an iron and ironing board please ask at the house. Breakfast is served between 8:30am and 9:00am. No allowance will be made for meals not taken. We would like to remind you that all our rooms are no smoking. We kindly request that you vacate your room between the hours of 10:30am and 1:30pm to allow us to clean. If you are unable to do so we will be happy just to top up your tea tray on request. On the day of departure we request that you vacate your room by 10:30am. All vehicles are parked at the owner’s risk and we do not accept any responsibility for the loss or damage of them. Please park to the rear of the building unless you require any assistance. We kindly request that when you return on an evening you are as quiet as possible for the comfort of all our guests. The proprietors cannot accept responsibility for the loss or damage of guest’s property unless handed in for safe custody. -

UK TV Outside Broadcast Fibre Connected Venues

UK TV Outside Broadcast fibre connected venues From UK venues to a North of England Arenas Middlesbrough FC Blackpool Winter Gardens Newcastle United FC worldwide audience Sheffield United FC Echo Arena Liverpool Manchester Arena Wigan Athletic FC Football and training Horse racing grounds Aintree Racecourse Barnfield (Burnley FC) Beverley Racecourse Burnley FC Carlisle Racecourse Carrington Complex Cartmel Racecourse (Man Utd FC) Catterick Racecourse Darsley Park (Newcastle FC) Chester Racecourse Etihad Complex (Man City FC) Haydock Racecourse Scotland Everton FC Market Rasen Racecourse Arenas St Johnstone FC Finch Farm (Everton FC) Pontefract Racecourse Hallam FM Academy Redcar Racecourse SEC Centre St Mirren FC (Sheff Utd FC) Thirsk Racecourse Football and Horse racing Leeds United FC Wetherby Racecourse training grounds Ayr Racecourse Leigh Sports Village York Racecourse Aberdeen FC Hamilton Racecourse Liverpool FC Celtic FC Kelso Racecourse Manchester City FC Rugby AJ Bell Stadium Dundee United FC Musselburgh Manchester United FC Leigh Sports Village Hamilton Academical Racecourse Melwood Training Ground FC Perth Racecourse (Liverpool FC) Newcastle Falcons Hibernian FC Rugby Kilmarnock FC Scotstoun Stadium Livingstone FC Motherwell FC Stadiums Rangers FC Hampden Stadium Ross County FC Murrayfield Stadium Midlands and East of England Arenas West Bromwich Albion FC Birmingham NEC Wolverhampton Coventry Ricoh Arena Wanderers FC Wales and Wolverhampton Civic Hall Horse racing Football and Cheltenham Racecourse training grounds Gloucester -

RPRA Rule Book 2020

THE OFFICIAL RULES 2020 Page 2 ROYAL PIGEON RACING ASSOCIATION OFFICERS 2020 President: Mr D. Bridges (3rd year) Vice-Presidents: Mr G. Cockshott (3rd year), Mr P. Hammond (2nd year), Mr J. Waters (2nd year) Trustees: Mr L. Blacklock, Mr D. Higgins, Mr R. Shirley PRESIDENT EX-OFFICIO MEMBER OF ALL COMMITTEES FInAnce & generAl PurPOses emergency & rules APPeAls clOcK, rIng & weATHer lIBerATIOn sITe L Blacklock – CA L Blacklock – CA L Blacklock – CA D Bridges – DY (Chair) D Bridges – DY (Chair) D Bridges – DY S Briggs – IR S Briggs – IR C O’Hare – IR J Dodd – EM J Heague – WE G Cockshott – NE J Gladwin – LN A Ewart – EM J Dodd – EM P Hammond – WM N Darby – WM R Harris – SO D Headon – DC J Gladwin – LN D Headon – DC D Higgins – NE D Headon – DC T Gardner – WS T Gardner – WS D Higgins – NE P Hammond – WM R Harris – SO C Gordon – NE S Mellor – NW S Mellor – NW R Shirley – SW T Gardner – WS E Hendrie – LN R Harris – SO J Waters – WE R Shirley – SW S Mellor – NW J Waters – WE (Chair) R Shirley – SW FuTure OF THe sPOrT OlymPIAD D Bridges – DY (Chair) BrITIsH HOmIng wOrlD L Blacklock – CA G Cockshott – NE L Blacklock – CA D Bridges – DY (Chair) D Higgins – NE D Bridges – DY (Chair) G Cockshott – NE J Heague – WE S Briggs – IR R Harris – SO J Dodd – EM J Waters – WE D Headon – DC P Hammond- WM J Dodd – EM R Harris – SO P Hammond – WM R Shirley – SW J Waters – WE D Headon – DC J Gladwin – LN E Hendrie – LN G Cockshott – NE T Gardner – WS R Harris – SO cOnFeDerATIOn OF lOng D Headon – DC DIsTAnce rAcIng PIgeOn T Gardner – WS PerFOrmAnce enHAncIng Drugs S Mellor – NW unIOns OF gB & IrelAnD R Shirley – SW D Bridges – DY D Bridges – DY (Chair) I Evans – CEO J Waters – WE J. -

T Am T Th T Be an C M in Fo Co Fa Gr W St Ch T Ra Sm in R No T Str W Fa

As a freelance writer, Alan Yuill Walker has spent The Scots & The Turf tells the story of the his life writing about racing and bloodstock. For amazing contribution made to the world of over forty years he was a regular contributor to Thoroughbred horseracing by the Scots and Horse & Hound and has had a long involvement those of Scottish ancestry, past and present. with the Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association. Throughout the years, this contribution has Other magazines/journals to which he has been across the board, from jockeys to trainers contributed on a regular basis include The and owners as well as some superb horses. British/European Racehorse, Stud & Stable, Currently, Scotland has a great ambassador in Pacemaker, The Thoroughbred Breeder and Mark Johnston, who has resurrected Middleham Thoroughbred Owner & Breeder. He was also in North Yorkshire as one of the country’s a leading contributor to The Bloodstock foremost training centres, while his jumping Breeders’ Annual Review. His previous books counterpart Alan King, the son of a Lanarkshire are Thoroughbred Studs of Great Britain, The farmer, is now based outside Marlborough. The History of Darley Stud Farms, Months of Misery greatest lady owner of jumpers in recent years Moments of Bliss, and Grey Magic. was Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, while Stirling-born Willie Carson was five-times champion jockey on the Flat. These are, of course, familiar names to any racing enthusiast but they represent just a small part of the Scottish connection that has influenced the Sport of Kings down the years. Recognition of the part played by those from north of the Border is long overdue and The Scots & The Turf now sets the record straight with a fascinating account of those who have helped make horseracing into the fabulous spectacle it is today. -

Lovesome Hill Farm

Lovesome Hill Farm Lovesome Hill Farm Contact Details: N*o+rthal0l1e2r3t4o5n6 N*o+rth Y0o1r2k3s4h5i6r7e8 D*L+6 2PB0 England Lovesome Hill Farm, Guest House, B&B in Northallerton,North Yorkshire.For more information on Lovesome Hill Farm,Northallerton Guest House, B&B please send an email enquiry to the owner. Facilities: Room Details: © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 27 September 2021 Lovesome Hill Farm Recommended Attractions 1. Aerial Extreme in North Yorkshire Childrens Attractions, Walking and Climbing A thrilling Adventure Ropes Course set on the grounds of the Kirklington, DL8 2LS, North Yorkshire, Camphill Estate in Kirklington North Yorkshire England 2. Outdoor Experiences in North Yorkshire Childrens Attractions, Cycling and Mountain Bikes, Shooting and Fishing, Guided Tours and Day Trips We offer Outdoor Experiences such as Off Road Quads and Felixkirk Thirsk, YO7 2DP, North Defenders Shooting and Fishing Segway Gliding in North Yorksire. Yorkshire, England Exclusive custom-built packages to provide a truly memorable experience. We also cater for kids. Phone: 01845 537 766 3. Lightwater Valley Family Theme Park North Yorkshire Festivals and Events, Lochs Lakes and Waterfalls, Childrens Attractions, Theme Parks A Theme Park with over 40 rides and attractions for thrill seekers of North Stainley, Ripon, HG4 3HT, North all ages including Europe's longest roller coaster-The Yorkshire, England Ultimate.Located near Ripon in North Yorkshire. Phone: 0871 720 0011 4. Ripon Races Yorkshire Racecourse Sports Venues, Horse Racing Ripon Racecourse recently won Best Small Racecourse in the North; The Racecourse, Boroughbridge Road, a fitting accolade and just description for what is a beautiful and Ripon, HG4 1UG, North Yorkshire, unique racecourse. -

Racecourse Guidance Document

SPECIAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF ENTRY TO ARC RACECOURSES CONTENTS SPECIAL CONDITIONS A - PARTICIPANTS IN RACING .............................. 3 23. Scope of Special Conditions A .............................................................. 3 24. Applicable Conditions ............................................................................ 3 SPECIAL CONDITIONS B - MEDIA CONTRACTORS AND LICENSEES ..... 5 25. Scope of Special Conditions B .............................................................. 5 26. Your Rights ........................................................................................... 5 27. Third Party Media Agreements to Prevail .............................................. 6 SPECIAL CONDITIONS C - PHOTOGRAPHERS ........................................... 7 28. Scope of Special Conditions C .............................................................. 7 29. Special Conditions for Holders of Photographers' Accreditation ........... 7 SPECIAL CONDITIONS D - PRESS ............................................................. 10 30. Scope of Special Conditions D ............................................................ 10 31. Special Conditions for Holders of Press Accreditation ........................ 10 SPECIAL CONDITIONS E - ON-COURSE BOOKMAKERS AND STAFF ..... 13 32. Scope and Duration of Special Conditions E....................................... 13 33. Special Conditions for Bookmakers .................................................... 14 SPECIAL CONDITIONS F - CONTRACTORS, TRADES AND EXHIBITORS ...................................................................................................................... -

125488 Nephrite Prospectus Intro.Qxp

THIS DOCUMENT AND ANY ACCOMPANYING DOCUMENTS ARE IMPORTANT AND REQUIRE YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek immediately your own personal financial advice from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other appropriate independent financial adviser, who is authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”) if you are in the United Kingdom or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred all of your Existing Shares (other than ex-rights) before 14 January 2010 (the “Ex-Rights Date”), please send this document, together with any Provisional Allotment Letter, duly renounced, if and when received, at once to the purchaser or transferee or to the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for delivery to the purchaser or transferee except that such documents should not be sent to any jurisdiction where to do so might constitute a violation of local securities laws or regulations, including but not limited to, subject to certain exceptions, the Excluded Territories. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred only part of your holding of Existing Shares (other than ex-rights) before the Ex-Rights Date, you should refer to the instruction regarding split applications in Part III (“Terms and Conditions of the Rights Issue”) of this document and in the Provisional Allotment Letter, if and when received. This document, which comprises a prospectus relating to the Rights Issue prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules, has been approved by the Financial Services Authority (the “FSA”) in accordance with Section 87A of FSMA PRA3 4.7 and made available to the public in accordance with Rule 3.2 of the Prospectus Rules. -

View Annual Report

Arena Leisure Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2010 More than a day at the races Arena Leisure Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2010 Horseracing lies at the heart of Arena’s activities. Our portfolio of racecourse assets provides a solid base for the future development of the Group into a range of complementary, income-generating activities that enhance our racing business and allow the expansion of our racecourses into 365 days a year operations. hospitality hotels all-weather and leisure turf and Áoodlit racing horseracing golf media broadcast exhibitions conferencing and events and banqueting Arena Leisure Plc 01 Annual Report and Accounts 2010 2010 Highlights Overview Overview 01 2010 Highlights 02 At a Glance 04 Chairman’s Statement 06 Chief Executive’s Statement Revenue £63,983,000 Strategy Strategy 2010 £63,983,000 2009 £65,239,000 08 Market Overview 11 Strategy and Business Model 13 Resources ReportDirectors’ and Business Review Adjusted profit before 14 Key Performance Indicators interest and tax £5,414,000 16 Principal Risks 2010 £5,414,000 2009 £4,904,000 Performance Operational highlights Performance 19 Review of Operations Average attendance increased by 4.2% 22 Managing Responsibly to 1,800 ahead of the market average 23 Financial Review growth of 3.4% Hospitality attendance increased by 17.1% to 45,200 At The Races delivered a 163% increase in post-tax contribution of £1.4m Governance Governance 25 Board of Directors and Company Secretary Development highlights 26 Corporate Governance 30 Other Statutory Information LingÀeld