Fall-A.-2010.Understanding-The-Casamance-Conflict-A-Background.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senegal, Between Migrations to Europe and Returns

The ITPCM International Commentary Vol. X no. 35 ISSN. 2239-7949 in this issue: in this issue: SENEGALSENEGAL BETWEEN MIGRATIONS TO EUROPE AND RETURNS April 2014 1 ITPCM International Commentary April 2014 ISSN. 2239-7949 International Training Programme for Conflict Management ITPCM International Commentary April 2014 ISSN. 2239-7949 The ITPCM International Commentary SENEGAL BETWEEN MIGRATIONS TO EUROPE AND RETURNS April 2014 ITPCM International Commentary April 2014 ISSN. 2239-7949 Table of Contents For an Introduction - Senegalese Street Vendors and the Migration and Development Nexus by Michele Gonnelli, p. 8 The Senegalese Transnational The Policy Fallacy of promoting Diaspora and its role back Home Return migration among by Sebastiano Ceschi & Petra Mezzetti, p. 13 Senegalese Transnationals by Alpha Diedhiou, p. 53 Imagining Europe: being willing to go does not necessarily result The PAISD: an adaptive learning in taking the necessary Steps process to the Migration & by Papa Demba Fall, p. 21 Development nexus by Francesca Datola, p. 59 EU Migration Policies and the Criminalisation of the Senegalese The local-to-local dimension of Irregular Migration flows the Migration & Development by Lanre Olusegun Ikuteyijo, p. 29 nexus by Amadou Lamine Cissé and Reframing Senegalese Youth and Jo-Lind Roberts, p. 67 Clandestine Migration to a utopian Europe Fondazioni4Africa promotes co- by Jayne O. Ifekwunigwe, p. 35 development by partnering Migrant Associations Senegalese Values and other by Marzia Sica & Ilaria Caramia, p. 73 cultural Push Pull Factors behind migration and return Switching Perspectives: South- by Ndioro Ndiaye, p. 41 South Migration and Human Development in Senegal Returns and Reintegrations in by Jette Christiansen & Livia Manente, p. -

Road Travel Report: Senegal

ROAD TRAVEL REPORT: SENEGAL KNOW BEFORE YOU GO… Road crashes are the greatest danger to travelers in Dakar, especially at night. Traffic seems chaotic to many U.S. drivers, especially in Dakar. Driving defensively is strongly recommended. Be alert for cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, livestock and animal-drawn carts in both urban and rural areas. The government is gradually upgrading existing roads and constructing new roads. Road crashes are one of the leading causes of injury and An average of 9,600 road crashes involving injury to death in Senegal. persons occur annually, almost half of which take place in urban areas. There are 42.7 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Senegal, compared to 1.9 in the United States and 1.4 in the United Kingdom. ROAD REALITIES DRIVER BEHAVIORS There are 15,000 km of roads in Senegal, of which 4, Drivers often drive aggressively, speed, tailgate, make 555 km are paved. About 28% of paved roads are in fair unexpected maneuvers, disregard road markings and to good condition. pass recklessly even in the face of oncoming traffic. Most roads are two-lane, narrow and lack shoulders. Many drivers do not obey road signs, traffic signals, or Paved roads linking major cities are generally in fair to other traffic rules. good condition for daytime travel. Night travel is risky Drivers commonly try to fit two or more lanes of traffic due to inadequate lighting, variable road conditions and into one lane. the many pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles sharing the roads. Drivers commonly drive on wider sidewalks. Be alert for motorcyclists and moped riders on narrow Secondary roads may be in poor condition, especially sidewalks. -

Rapport EV 2009 Cartes Rev-Mai 2011 Mb MF__Dsdsx

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ---------- MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES ---------- Cellule de Suivi du Programme de Lutte contre la Pauvreté (CSPLP) ---------- Projet d’Appui à la Stratégie de Réduction de la Pauvreté (PASRP) Avec l’appui de l’union européenne ENQUETE VILLAGES DE 2009 SUR L'ACCES AUX SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE Rapport final Dakar, Décembre 2009 SOMMAIRE I. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATIONS _____________________________________________ 3 II. OBJECTIF GLOBAL DE L’ENQUETE VILLAGES __________________________________ 3 III. ORGANISATION ET METHODOLOGIE ________________________________________ 5 III.1 Rationalité ______________________________________________________________ 5 III.2 Stratégie ________________________________________________________________ 5 III.3 Budget et ressources humaines _____________________________________________ 7 III.4 Calendrier des activités ____________________________________________________ 7 III.5 Calcul des indices et classement des communautés rurales _______________________ 9 IV. Analyse des premiers résultats de l’enquête _______________________________ 10 V. ACCES ET EXISTENCE DES SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE _________________________ 11 VI. Accès et fonctionnalité des services sociaux de base ________________________ 14 VII. Disparités régionales et accès aux services sociaux de base __________________ 16 VII.1 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un lieu de commerce ___________________________ 16 VII.2 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un point d’eau potable _________________________ -

Calcium Phosphate of Kolda Reasons to Invest?

CALCIUM PHOSPHATE OF KOLDA REASONS TO INVEST? Phosphates have been the main mineral used in Senegal with a good contribution to the country's GDP. For example, the use of phosphates began in 1949 for aluminum Thiès. Besides this western part, there is a deposit in Matam in the north, some indices in the central region (Kaolack, Fatick, Diourbel, Louga, Kaffrine) and southern (Kolda and Ziguinchor). This paper aims to study the host country, its legal framework and geological order to justify the exploitation and utilization of calcium phosphate in Kolda. CALCIUM PHOSPHATE OF KOLDA OVERVIEW OF SENEGAL Situated in the extreme west of the African continent, Senegal is located between 12 ° 8:16 ° 41 north latitude and 11 ° 21 and 17 ° 32 west longitude. The country is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Mauritania to the north, La ré gion dé Mali to the east, Guinea Bissau Guinea to the south and the KoldaThé région of southeast. The Gambia is an enclave in southern Senegal in Kolda length within which penetrates deeply. With an area of La région de Kolda The Kolda region has 3 196,722 km2, Senegal, with Dakar as capital, has 12 million compte trois (03) inhabitants distributed evenly so the 14 administrative departments, 9 districts départements, neuf (09) regions (density of 61.1 ² hab / km and the population and 31 rural growth rate: 2.34 %). arrondissements neuf communities. With an (09) communes et trente area of 21011 km ², une (31) communautés Kolda has 847,243 rurales. Avec une inhabitants with a superficie de 21011 km², density of 40 inhabitants Kolda compte 847243 / km ². -

Communauté Rurale OULAMPANE

République du Sénégal Un peuple – Un but – Une foi MINISTERE DE L’HABITAT, DE LA MINISTERE DE L’URBANISME ET DE CONSTRUCTION ET DE L’HYDRAULIQUE L’ASSAINISSEMENT Région de ZIGUINCHOR PLAN LOCAL D’HYDRAULIQUE ET D’ASSAINISSEMENT -PLHA Communauté rurale OULAMPANE (Version finale) JUILLET 2010 Ce document est réalisé sur financement de l’Agence Américaine pour le Développement International (USAID) dans le cadre de son appui au Gouvernement du Sénégal 1 USAID/PEPAM Millennium Water and Sanitation Program Programme d’Eau Potable et d’Assainissement du Millénaire Cooperative Agreement No 685-A-00-09-00006-00 Accord de cooperation n°685-A-00-09-00006-00 PREPARED FOR / PRÉPARÉ À L’ATTENTION DE Prepared by / Préparé par Agathe Sector RTI International Agreement Officer’s Representative 3040 Cornwallis Road Office of Economic Growth Post Office Box 12194 USAID/Senegal Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194 Route des Almadies Phone: 919.541.6000 Almadies BP 49 Dakar, Senegal http://www.rti.org SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. 4 FICHE DE SYNTHESE PLHA............................................................................................................................ 5 I. PRÉSENTATION DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ RURALE ................................................................................ -

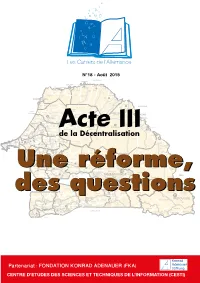

Acte III Une Réforme, Des Questions Une Réforme, Des Questions

N°18 - Août 2015 MAURITANIE PODOR DAGANA Gamadji Sarré Dodel Rosso Sénégal Ndiandane Richard Toll Thillé Boubakar Guédé Ndioum Village Ronkh Gaé Aéré Lao Cas Cas Ross Béthio Mbane Fanaye Ndiayène Mboumba Pendao Golléré SAINT-LOUIS Région de Madina Saldé Ndiatbé SAINT-LOUIS Pété Galoya Syer Thilogne Gandon Mpal Keur Momar Sar Région de Toucouleur MAURITANIE Tessekéré Forage SAINT-LOUIS Rao Agnam Civol Dabia Bokidiawé Sakal Région de Océan LOUGA Léona Nguène Sar Nguer Malal Gandé Mboula Labgar Oréfondé Nabbadji Civol Atlantique Niomré Région de Mbeuleukhé MATAM Pété Ouarack MATAM Kelle Yang-Yang Dodji Gueye Thieppe Bandègne KANEL LOUGA Lougré Thiolly Coki Ogo Ouolof Mbédiène Kamb Géoul Thiamène Diokoul Diawrigne Ndiagne Kanène Cayor Boulal Thiolom KEBEMER Ndiob Thiamène Djolof Ouakhokh Région de Fall Sinthiou Loro Touba Sam LOUGA Bamambé Ndande Sagata Ménina Yabal Dahra Ngandiouf Geth BarkedjiRégion de RANEROU Ndoyenne Orkadiéré Waoundé Sagatta Dioloff Mboro Darou Mbayène Darou LOUGA Khoudoss Semme Méouane Médina Pékesse Mamane Thiargny Dakhar MbadianeActe III Moudéry Taïba Pire Niakhène Thimakha Ndiaye Gourèye Koul Darou Mousty Déali Notto Gouye DiawaraBokiladji Diama Pambal TIVAOUANE de la DécentralisationRégion de Kayar Diender Mont Rolland Chérif Lô MATAM Guedj Vélingara Oudalaye Wourou Sidy Aouré Touba Région de Thiel Fandène Thiénaba Toul Région de Pout Région de DIOURBEL Région de Gassane khombole Région de Région de DAKAR DIOURBEL Keur Ngoundiane DIOURBEL LOUGA MATAM Gabou Moussa Notto Ndiayène THIES Sirah Région de Ballou Ndiass -

Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850

The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Benjamin, Jody A. 2016. The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493374 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 A dissertation presented by Jody A. Benjamin to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African and African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2016 © 2016 Jody A. Benjamin All rights reserved. Dissertation Adviser: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Jody A. Benjamin The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 Abstract This study re-examines historical change in western Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the lens of cotton textiles; that is by focusing on the production, exchange and consumption of cotton cloth, including the evolution of clothing practices, through which the region interacted with other parts of the world. It advances a recent scholarly emphasis to re-assert the centrality of African societies to the history of the early modern trade diasporas that shaped developments around the Atlantic Ocean. -

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance Perspectives from Women and Local Populations August 2019 Content 3. Acronyms & Abbreviations 4. Acknowledgements 5. Foreword 7. Cry For Action Of The Women Of Casamance! 8. Preface 9. Introduction 9. Context 11. Historical background of the conflict and the peace process 13. The Conflict’s Impacts On Local Populations, Women And Youth 13. Socioeconomic and environmental impacts 15. Casamance populations’ perceptions and feelings of exclusion 17. The conflict’s specific impacts on women 18. A permanent insecurity 19. Strategies And Perspectives From Civil Society 20. Civil society actors 21. Addressing challenges and establishing peace 23. Actions and approaches 25. Conditions for effective and inclusive participation 26. Women’s participation in peace processes 26. The mediation role of women of Casamance 27. La Plateforme des Femmes pour la Paix en Casamance (PFPC) 28. Senegambia Forum 29. Breaking down barriers and strengthening support across women throughout Senegal 30. Recommendations for a definitive & sustainable peace in Casamance 34. Bibliography 35. Annexes 49. Endnotes Acronyms & Abbreviations AFUDES Association of United Brothers for the Economic and Social Development of the Fogny ASC Sports and Cultural Association AJAEDO Association des Jeunes Agriculteurs et Éleveurs du Département d'Oussouye AJWS American Jewish World Service (NGO) ANRAC Agence nationale pour la Relance des Activités économiques en Casamance ANSD Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie -

Guinea-Bissau After Vieira: Challenges and Opportunities

THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS 20/1999 Guinea-Bissau after Vieira: Challenges and Opportunities On 7 June 1998, an army mutiny led by former Chief of Staff, General Ansumane Mane, plunged the Republic of Guinea-Bissau into a devastating civil war. The coup aimed to oust President Joao Bernardo Vieira, who had come to power in a military coup against Luis Cabral in 1980 and had subsequently won the country's first multiparty elections in 1994. The civil war that followed Mane's mutiny changed the framework of the ongoing transformation process in the former socialist-orientated Guinea-Bissau. It also engulfed the subregion drawing Senegal, Guinea and The Gambia into the power struggle in Guinea- Bissau. In May 1999, after a peace process had already been did not install a military regime after he came to negotiated and partially implemented, Mane's forces power. With the beginning of democratic transition launched another attack on Vieira, and finally in 1990, the military lost its remaining privileges and succeeded in ousting the incumbent leader. Although became part of the marginalised population. Major this coup can be seen as a setback for peace and sections of the army started relying on proceeds from reconciliation in Guinea-Bissau, the new political illicit arms deals with the Casamance rebels and situation that resulted from Vieira's overthrow at least cannabis sales. provided a chance to end a hitherto paralysing state of 'no peace-no war' — akin to the Angolan situation The regional dimension after the Lusaka Accords. The new power G iven Mane's control over major sections of the army, constellation under Mane may well give Vieira's Vieira had to fight the rebellion with the military rather disappointing democratisation assistance of Guinea (400 soldiers) and process fresh impetus. -

2014 Mowglis Call

The Mowglis Call 2014 Nick Robbins .................. [email protected] Holly Taylor ................................ [email protected] Tommy Greenwell ........ [email protected] FIND US ON FACEBOOK! Please join our group to keep up with the latest Mowglis events, see photos from last summer, and reconnect with old friends. We’re currently over 460 members strong! www.facebook.com/groups/CampMowglisGroup/ Please send us your email address! Send updates to: [email protected] HOLT-ELWELL MEMORIAL In This Issue FOUNDATION President’s Message ........................................................................2 TRUSTEES Director’s Message ...........................................................................3 Christopher A. Phaneuf Assistant Director’s Letter ..............................................................4 President Remembering Allyn Brown ......................................................... 5-8 Weston, Mass. New Woodworking Shop ................................................................8 Jim Westberg Vice President Wayne King: Doing Good, Doing Well ....................................9-11 Nashua, N.H. Alumni and Recruiting Events ......................................................12 David Tower Kenyon Salo: Leading the Bucket List Life ......................... 15-16 Treasurer Malvern, Pa. Alejandro and Raul Medina-Mora Return to Mowglis ...........17 Richard Morgan 2014 Contributors ................................................................... 18-19 Secretary N. Sandwich, N.H. Alumni -

Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, Stability Challenges and Prospects

Annan, N 2014 Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, stability Challenges and Prospects. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, 3(1): 3, pp. 1-16, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/sta.da RESEARCH ARTICLE Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, Challenges and Prospects Nancy Annan* The advent of intra-state conflicts or ‘new wars’ in West Africa has brought many of its economies to the brink of collapse, creating humanitarian casualties and concerns. For decades, countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea- Bissau were crippled by conflicts and civil strife in which violence and incessant killings were prevalent. While violent conflicts are declining in the sub-region, recent insurgencies in the Sahel region affecting the West African countries of Mali, Niger and Mauritania and low intensity conflicts surging within notably stable countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal sends alarming signals of the possible re-surfacing of internal and regional violent conflicts. These conflicts are often hinged on several factors including poverty, human rights violations, bad governance and corruption, ethnic marginalization and small arms proliferation. Although many actors including the ECOWAS, civil society and international community have been making efforts, conflicts continue to persist in the sub-region and their resolution is often protracted. This paper posits that the poor understanding of the fundamental causes of West Africa’s violent conflicts and civil strife would likely cause the sub-region to continue experiencing and suffering the brunt of these violent wars. Introduction 24). While violent conflicts are declining in The transformation from inter-state to intra- the sub-region, recent insurgencies in the state conflict from the latter part of the 20th Sahel region affecting the West African coun- Century in West Africa brought a number of tries of Mali, Niger and Mauritania sends its economies to near collapse. -

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Senegal: Is the Practice Declining? Descriptive Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys, 2005–2017

Population Council Knowledge Commons Reproductive Health Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 2-28-2020 Female genital mutilation/cutting in Senegal: Is the practice declining? Descriptive analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys, 2005–2017 Dennis Matanda Population Council Glory Atilola Zhuzhi Moore Paul Komba Lubanzadio Mavatikua See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Medicine and Health Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Matanda, Dennis, Glory Atilola, Zhuzhi Moore, Paul Komba, Lubanzadio Mavatikua, Chibuzor Christopher Nnanatu, and Ngianga-Bakwin Kandala. 2020. "Female genital mutilation/cutting in Senegal: Is the practice declining? Descriptive analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys, 2005-2017," Evidence to End FGM/C: Research to Help Girls and Women Thrive. New York: Population Council. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. Authors Dennis Matanda, Glory Atilola, Zhuzhi Moore, Paul Komba, Lubanzadio Mavatikua, Chibuzor Christopher Nnanatu, and Ngianga-Bakwin Kandala This report is available at Knowledge Commons: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/ 1079 TITLE WHITE TEXT FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION / CUTTING IN SENEGAL:TITLE ON IS TOPTHE OF