The Wadham Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Biden Spotted in Trump Statue Park Kissing Bronze Hair of Shirley Temple //DIANA KOLSKY

FEB 8, 2021//VOL. IV, ISSUE 3 BRB, gearing up for the ensuing Pillow Fights. 2 FD Exclusive: Governor Cuomo to COVID Task Force: “Have We Tried Peeing on the Virus?” //JAMES DWYER 4 President Biden Spotted in Trump Statue Park Kissing Bronze Hair of Shirley Temple //DIANA KOLSKY 5 The Trade-In Value on this Gamestop Stock Sucks //BRADY O'CALLAHAN 6 Where Are The $2,000 Checks? We’re Building an Army of Harriet Tubman Clones to Deliver Them as We Speak //MATTHEW BRIAN COHEN 8 Pitchfork Reviews Ariel Pink & John Maus Debut Collaboration, We The People //MICHAEL "PORTLAND MIKE" KNACKSTEDT GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 10 Paid Advertisement: The Cancelled Crate™ //THE FUNCTIONALLY DEAD HEADS 11 This Quarantine Valentine’s Day, Give Them a Gift They’ll Love: One Goddamn Day Alone //AMANDA PORYES GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 13 14 Functionally Dead Investment Newsletter: Think Like A Stock //MATTHEW BRIAN COHEN 15 Salute to Our Inessential Workers //THE FUNCTIONALLY DEAD HEADS 18 Marriage Is a Capitalist Institution, Mom (and I Can't Find Anyone Who Likes Me for Me) //ANDREW BARLOW GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 20 Dr. Jill Biden Gave Me CPR, and I Died for Seven Minutes //DIANA KOLSKY 21 Teen Militia Member Weighs Pros and Cons of Listing His Oath Keepers Affiliation on College Application //CAMILLE TINNIN GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 23 What Do I Do Now? //DAN LOPRETO THIS IS A MAGAZINE OF PARODY, SATIRE, AND OPINION//DESIGNED BY DIANA KOLSKY 1 FD EXCLUSIVE Governor Cuomo to COVID Task Force: “Have We Tried Peeing on the Virus?” //JAMES DWYER FD has secured access to a recording from a recent phone call between NY Governor Andrew Cuomo and his COVID Task Force. -

2015 Year in Review

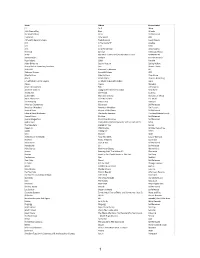

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Tbc + James Maad John Maus + Tulsa Pop Rock + Pheromone Blue Lo-Fi Stagers! Electrónica Open Mic 2.0

1 de 17 PROGRAMACIÓN NOVIEMBRE 2017 Domingo 5 Jueves 2, 21:00 Viernes 3, 21:00 Sábado 4, 22:00 Miércoles 1 19:00 Entrada libre Ant 9€ / Taq 12 € Taq 20 € Ant 10 € / Taq 12 € 21:00 Entrada libre BALCONY TV ELECTRO EL HOMBRE LUNA NIGTH MOMENTOS ALHAMBRA RADIO SHOW: MÚSICA PRESENTA NATHY FARIA DESTINO 48 FUEL FANDANGO TBC + JAMES MAAD JOHN MAUS + TULSA POP ROCK + PHEROMONE BLUE LO-FI STAGERS! ELECTRÓNICA OPEN MIC 2.0 Jueves 9, 22:00 Viernes 10, 22:00 Domingo 12, 21:00 Sábado 11, 22:00 Miércoles 8 Ant 7 € / Taq 9 € Ant 8 € / Taq 9 € Ant 6 € / Taq 7 € Ant 8 € / Taq 10 € (Incluye consumición) (Incluye consumición) (Incluye consumición) GANADORES EL CUARTO DE THE LOW FLYING LEMOND INVITADOS PANIC ATTACK STAGERS! TBC POP POP ROCK INDIE INDIE FOLK Miércoles 15, 21:00 Jueves 16, 22:00 Viernes 17, 22:00 Sábado 18, 22:00 Domingo 19 19:00 Entrada libre Ant / Taq 22 € Ant 8 € / Taq 11 € Ant 8 € / Taq 10 € Ant 10 € / Taq 12 € 21:00 Entrada libre (Incluye cocktail Ginger 43) (Incluye consumición) (Incluye consumición) (Incluye consumición) EL HOMBRE LUNA RADIO SHOW: JÄGERMUSIC PRESENTA HONKY TONKY UN BUEN CLUB ALBERTO AZUL SÁNCHEZ + ROZALEN MANS O + CEDEZAOITO EL CHOJIN PEDRO PERLES + MARTIRIO RAP / HIP HOP ELECTRÓNICA INDIE ROCK BLUES / ROCK STAGERS! OPEN MIC 2.0 Miércoles 22, 21:00 Sábado 25, 22:00 Domingo 26, 20:30 Jueves 23, 22:00 Viernes 24, 22:00 Ant 5 € / Taq 7 € Ant 8 € / Taq 11 € Ant 11,5€ / Taq 13,5 € Ant 10 € / Taq 12 € Ant 10 € / Taq 12 € (Incluye consumición) (Incluye consumición) (Incluye consumición) LA PICCOLA SPAÑISH COSMOSOUL SEYDINA NDIAYE FERNANDO BAZÁN BANDA + LOCAL QUA4TRO BURLESQUE ESOTÉRICA SHOW MÚSICAS NEGRAS MÚSICAS NEGRAS INDIE ROCK ELECTROCUMBIA BURLESQUE Miércoles 29, 21:00 Jueves 30, 22:00 Ant / Taq 22 € (Incluye cocktail Ginger 43) Ant 10 € / Taq 12 € UN BUEN CLUB FORASTERO EL CHOJIN JAZZ FUSION RAP / HIP HOP CAFÉ LA PALMA. -

OFF Festival Katowice 2018 Announcing the First Artists We’Re Pleased to Announce the First Artists That Are Confirmed to Perform at the Next OFF Festival

OFF Festival Katowice 2018 Announcing the First Artists We’re pleased to announce the first artists that are confirmed to perform at the next OFF Festival. They’re original, they’re psychedelic and they’re kaleidoscopic: Grizzly Bear, Clap Your Hands Say Yeah performing Some Loud Thunder, John Maus and Marlon Williams are coming to Katowice in August. Get your OFF Festival passes now at a special early- bird prices. There’s no better Christmas gift than that! Grizzly Bear If there’s one band on the US indie scene today that can blaze new trails in American folk music while remaining faithful to the lessons of the Beach Boys, and that can be as catchy as they are challenging, blending jazz and art rock with pop, then that band is, without a doubt, Grizzly Bear. But it would be unfair to brand this Brooklyn quartet as a group of savvy counterfeiters: their music — a dense web of gripping and at times slightly psychedelic sonic ideas — is a purely original invention. It’s also one that’s garnered rave reviews from audiences and critics alike since their debut Horn of Plenty (2004). Grizzly Bear’s follow-up Yellow House (ranked among the top albums of 2006 by The New York Times and Pitchfork) secured their spot in the top echelons of alternative rock, while later efforts, including this year’s Painted Ruins, only reinforced their status. But as we’ll all see on a warm summer night this August, this bear’s natural habitat is the stage. John Maus His music has been described as a mash-up of punk, catchy soundtracks to ‘80s blockbusters, the unremitting poppiness of Moroder, and the spiritual qualities of Medieval and Baroque music. -

Scott Walker and the Late Twentieth Century Phenomenon of Phonographic Auteurism Duncan G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Scott Walker and the Late Twentieth Century Phenomenon of Phonographic Auteurism Duncan G. Hammons Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC SCOTT WALKER AND THE LATE TWENTIETH CENTURY PHENOMENON OF PHONOGRAPHIC AUTEURISM By DUNCAN G. HAMMONS A Thesis Submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2013 Duncan Hammons defended this thesis on April 4, 2013 The members of the supervisory committee were: Kimberly VanWeelden Professor Directing Thesis Jane Clendinning Professor Co-Directing Thesis Frank Gunderson Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii Dedicated to my family and friends for their endless encouragements and many stimulating conversations that fostered the growth of my curiosity in this subject, and the memory of my father, Charles Edwin Hammons (November 1, 1941 - April 28, 2012), who taught me the invaluable lesson of consolidating work and play. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the members of my supervisory committee, Dr. Jane P. Clendinning, Dr. Kimberly VanWeelden and Dr. Frank Gunderson for their enthusiasm and generosity in their guidance of this research, and additionally, Dr. Laura Lee and Dr. Barry Faulk for lending their expertise and additional resources to the better development of this work. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ...............................................................................................................................vii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................viii 1. -

Slugmag.Com 1

slugmag.com 1 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 25 • Issue #311 • November 2014 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Coordinator: CONTRIBUTOR LIMELIGHT: Editor: Angela H. Brown Robin Sessions Managing Editor: Alexander Ortega Marketing Team: Alex Topolewski, Carl Acheson, Alex Springer Junior Editor: Christian Schultz Cassie Anderson, Cassandra Loveless, Ischa B., Janie Senior Staff Writer Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan Greenberg, Jono Martinez, Kendal Gillett, Lindsay Digital Content Coordinator: Henry Glasheen Clark, Raffi Shahinian, Robin Sessions, Zac Freeman Fact Checker: Henry Glasheen Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer Copy Editing Team: Alex Cragun, Alexander Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Ortega, Allison Shephard, Christian Schultz, Cody Distro: Andrea Silva, Daniel Alexander, Eric Kirkland, Henry Glasheen, John Ford, Jordan Granato, John Ford, Jordan Deveraux, Julia Sachs, Deveraux, Julia Sachs, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Maria Valenzuela, Michael Sanchez, Nancy Maria Valenzuela, Mary E. Duncan, Shawn Soward, Burkhart, Nancy Perkins, Phil Cannon, Ricky Vigil, Traci Grant Ryan Worwood, Tommy Dolph, Tony Bassett, Content Consultants: Jon Christiansen, Xkot Toxsik Matt Hoenes Senior Staff Writers: Alex Springer, Alexander Cover Photo: Chad Kirkland Ortega, Ben Trentelman, Brian Kubarycz, Brinley Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Froelich, Bryer Wharton, Christian Schultz, Cody Design Team: Chad Pinckney, Lenny Riccardi, Hudson, Cody Kirkland, Dean O. Hillis, Gavin Mason Rodrickc, Paul Mason Sheehan, Henry Glasheen, Ischa -

GAVIN FRIDAY Peek Aboo

edition October - December 2012 peek free of charge, not for sale 07 music quarterly published music magazine aboo magazine GAVIN FRIDAY BLANCMANGE AGENT SIDE GRINDER THE BOLLOCK BROTHERS THE BREATH OF LIFE + MIREXXX + SIMI NAH + DARK POEM + EISENFUNK + IKE YARD + JOB KARMA + METROLAND + 7JK + THE PLUTO FESTIVAL - 1 - WOOL-E-TOP 10 WOOL-E-TIPS Best Selling Releases DARK POEM (July/Aug/Sept 2012) TALES FROM THE SHADES 1. DIVE STACKS Dive Box (8CD) VOICES 2. SONAR Cut Us Up (CD) 3. VARIOUS ARTISTS Miniroboter (LP) 4. TROPIC OF CANCER Permissions Of Love (12”) 5. VARIOUS ARTISTS Something Cold (LP) 6. SSLEEPING DESIRESS Because we can’t choose not one, but two Wool-E A Voice (7”) tips!!! ‘Tales From The Shades’ is the debut CD by Ant- 7. VARIOUS ARTISTS werp-based ‘Fairyelectro’ band Dark Poem. Doomy tribal The Scrap Mag (CD) pop with heavenly voices set to a dark ambient-like under- 8. LOWER SYNTH DEPARTMENT score, with enough rough hooks to keep you wandering through their fairy wood. Beware of the Forrest Nymphs!!! Plaster Mould(LP) Our second tip also resides in Antwerp, ‘Voices’ is the 9. BONJOUR TRISTESSE debut LP of Stacks aka Sis Mathé of indie noiserockers On Not Knowing Who We Are (LP) White Circle Crime Club. Touches of John Maus, Molly 10. GAY CAT PARK Nilsson, Future Islands or even Former Ghosts come to mind. So if you like your synthpop bombastic and emo- Synthetic Woman (LP) tional, straight from the heart, then Stacks is your man or your band ;-) The Wool-E Shop - Emiel Lossystraat 17 - 9040 Ghent - Belgium VAT BE 0642.425.654 -

Wolfgang Tillmans Bibliography

WOLFGANG TILLMANS BIBLIOGRAPHY Selected Monographs: 2021 Holert, Tom, and Klaus Pollmeier, Saturated Light: Wolfgang Tillmans, Silver Works, published by Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, and Verlag der Buchhandlung Franz und Walther König, Cologne, Germany, 2021 2020 Tillmans, Wolfgang, Wolfgang Tillmans: Today Is The First Day, published by Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, WIELS, Brussels, and Koenig Books, London, UK, 2020 2018 Biswas, Allie, and Wolfgang Tillmans, Wolfgang Tillmans: DZHK Book 2018, published by David Zwirner Books, New York, NY, 2018 Eyene, Christine, N’Goné Fall, Bart van der Heide, and Ashraf Jamal, Wolfgang Tillmans: Fragile, published by Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen, Stuttgart, Germany, 2018 2017 Tillmans, Wolfgang, and Brigitte Oetker, eds., Was ist anders? Jahresring 64, published by Sternberg Press, Berlin, Germany, 2017 Tillmans, Wolfgang, and Theodora Vischer, Wolfgang Tillmans, published by Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern, Germany, 2017 Tillmans, Wolfgang, Hamburg Süd / Nee IYaow Eow Eow, CD Digipack + artist booklet, published by Fragile, and Kunstverein Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, 2017 Dercon, Chris, Mark Godfrey, Tom Holert, and Helen Sainsbury, Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017, published by Tate Publishing, London, UK, 2017 2016 Needham, Alex, Conor Donlon, published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne, Germany, 2016 Cotter, Suzanne, Wolfgang Tillmans: On the Verge of Visibility, published by Serralves Foundation, Porto, Portugal, 2016 McDonough, Tom, What’s wrong with redistribution?, published by Verlag -

Notes from the Underground: a Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music

Notes From The Underground: A Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music. Stephen Graham Goldsmiths College, University of London PhD 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: …………………………………………………. Date:…………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract The term ‗underground music‘, in my account, connects various forms of music-making that exist largely outside ‗mainstream‘ cultural discourse, such as Drone Metal, Free Improvisation, Power Electronics, and DIY Noise, amongst others. Its connotations of concealment and obscurity indicate what I argue to be the music‘s central tenets of cultural reclusion, political independence, and aesthetic experiment. In response to a lack of scholarly discussion of this music, my thesis provides a cultural, political, and aesthetic mapping of the underground, whose existence as a coherent entity is being both argued for and ‗mapped‘ here. Outlining the historical context, but focusing on the underground in the digital age, I use a wide range of interdisciplinary research methodologies , including primary interviews, musical analysis, and a critical engagement with various pertinent theoretical sources. In my account, the underground emerges as a marginal, ‗antermediated‘ cultural ‗scene‘ based both on the web and in large urban centres, the latter of whose concentration of resources facilitates the growth of various localised underground scenes. I explore the radical anti-capitalist politics of many underground figures, whilst also examining their financial ties to big business and the state(s). This contradiction is critically explored, with three conclusions being drawn. First, the underground is shown in Part II to be so marginal as to escape, in effect, post- Fordist capitalist subsumption. -

Rebel Issue Savages the Go Go's

a magazine about female drummers TOM TOM MAGAZINE summer 2014 #18: the rebel issue rebel issue sa va ges Fay Milton Kris Ramos of STOMP Didi Negron of the Cirque du Soleil Go go’s Gina Schock Alicia Warrington ISSUE 18 | USD $6 DISPLAY SUMMER 2014 kate nash CONTRIBUTORS INSIDE issUE 18 FOUNDER/pUblishER/EDiTOR-iN-ChiEF Mindy Abovitz ([email protected]) BACKSTAGE WITH STOMP maNagiNg EDitor Melody Allegra Berger 18 REViEWs EDitor Rebecca DeRosa ([email protected]) DEsigNERs Candice Ralph, Marisa Kurk & My Nguyen CIRQUE DU SOLEIL CODERs Capisco Marketing 20 WEb maNagER Andrea Davis NORThWEsT CORREspONDENT Lisa Schonberg PLANNINGTOROCK NORThWEsT CREW Katherine Paul, Leif J. Lee, Fiona CONTRibUTiNg WRiTER Kate Ryan 24 Campbell, Kristin Sidorak la CORREspONDENTs Liv Marsico, Candace Hensen OUR FRIENDS HABIBI miami CORREspONDENT Emile Milgrim 26 bOston CORREspONDENT Kiran Gandhi baRCElONa CORREspONDENT Cati Bestard NyC DisTRO Segrid Barr ALICIA WARRINGTON/KATE NASH EUROpEaN DisTRO Max Markowsky 29 COpy EDiTOR Anika Sabin WRiTERs Chloe Saavedra, Rachel Miller, Shaina FAY FROM SAVAGES Machlus, Sarah Strauss, Emi Kariya, Jenifer Marchain, Cassandra Baim, Candace Hensen, Mar Gimeno 32 Lumbiarres, Kate Ryan, Melody Berger, Lauren Flax, JD Samson, Max Markowsky illUsTRator Maia De Saavedra TEChNiqUE WRiTERs Morgan Doctor, Fernanda Terra gina from the go-go’s Vanessa Domonique 36 phOTOgRaphERs Bex Wade, Ikue Yoshida, Chloe Aftel, Stefano Galli, Cortney Armitage, Jessica GZ, John Carlow, Annie Frame SKIP THE NEEDLE illUsTRaTORs Maia De Saavedra -

1 Ervin Jarek 2017 PHD.Pdf

ii © Copyright by Jarek Paul Ervin All Rights Reserved May 2017 iii ABSTRACT My dissertation takes a speculative cue from the reception of 1970s New York punk, which is typically treated as both rule – the symbolic site of origin – and exception – a protean moment before the crystallization of punk proper. For this reason, artists such as Velvet Underground, Patti Smith, the Ramones, and Blondie are today afforded the simultaneous status of originators, interlopers, innovators, and successors. This has led both to the genre’s canonicity in the music world and its general neglect within scholarship. I argue that punk ought to be understood less as a set of stylistic precepts (ones that could be originated and then developed), than as a set of philosophical claims about the character of rock music in the 1970s. Punk artists such as Patti Smith, Jayne County, and the Ramones developed an aesthetic theory through sound. This was an act of accounting, which foregrounded the role of historical memory and recast a mode of reflexive imagination as musical practice. At times mournful, at times optimistic about the possibility of reconciliation, punk was a restorative aesthetics, an attempt to forge a new path on memories of rock’s past. My first chapter looks at the relationship between early punk and rock music, its ostensible music parent. Through close readings of writing by important punk critics including Greil Marcus, Lester Bangs, and Ellen Willis – as well as analyses of songs by the Velvet Underground and Suicide – I argue that a historical materialist approach offers a new in-road to old debates about punk’s progressive/regressive musical character. -

The Hypermodern Anti-Comedy of Tim and Eric, Eric André and Million Dollar Extreme

“The Dada of Haha”: The Hypermodern Anti-Comedy of Tim and Eric, Eric André and Million Dollar Extreme Alexandra Warrick The Department of Film Studies, Columbia University Professor Richard Pena February 1st, 2016 1 SMASHING THE LIVING ROOM: AN INTRODUCTION Potted plants, a couch. A desk, a chair. Brown curtains, columns, a tabletop globe. Picture a comedy talk show set outfitted with these staples: homey, right? Comforting? It might, for you, invoke a living room; after all, as Michael Shapiro writes, “the family-like living room of the talk-show set…functions as a theatrical stage to forge intimate connections with the friends and family of the nation.” (Shapiro 32) Think, for a moment, on the worn-in “living rooms” offered by our nation’s most beloved comedy programs: the quirky clutter of Seinfeld, the stylized skyline of the Tonight Show, the comforting glow of Saturday Night Live’s faux-Grand Central spread. We know these spaces perhaps better than we do our own living rooms; the latter mutable, the former dependable. We come upon these shared “living rooms” and we, Pavlov’s audience, know that it’s time to laugh. Comedy becomes a warm, bubbling cordial that brings us, the Shapiro-style nation-as-family, together; in indulging in our shared national sense of humor, we as a culture bond together as we settle into the cozy cosmic couch these comedy programs offer us. With this in mind, once again picture the comedy talk show set. Now picture a man bursting from the wings to violently, viciously kick it to pieces.