Why Aren't Comics Funny Anymore?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

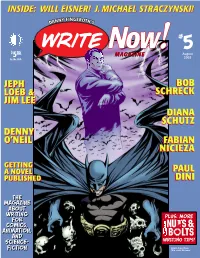

Inside: Will Eisner! J. Michael Straczynski!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: WWIILLLL EEIISSNNEERR!! JJ.. MMIICCHHAAEELL SSTTRRAACCZZYYNNSSKKII!! $ 95 MAGAAZZIINEE August 5 2003 In the USA JJEEPPHH BBOOBB LLOOEEBB && SSCCHHRREECCKK JJIIMM LLEEEE DIANA SCHUTZ DDEENNNNYY OO’’NNEEIILL FFAABBIIAANN NNIICCIIEEZZAA GGEETTTTIINNGG AA NNOOVVEELL PPAAUULL PPUUBBLLIISSHHEEDD DDIINNII Batman, Bruce Wayne TM & ©2003 DC Comics MAGAZINE Issue #5 August 2003 Read Now! Message from the Editor . page 2 The Spirit of Comics Interview with Will Eisner . page 3 He Came From Hollywood Interview with J. Michael Straczynski . page 11 Keeper of the Bat-Mythos Interview with Bob Schreck . page 20 Platinum Reflections Interview with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg . page 30 Ride a Dark Horse Interview with Diana Schutz . page 38 All He Wants To Do Is Change The World Interview with Fabian Nicieza part 2 . page 47 A Man for All Media Interview with Paul Dini part 2 . page 63 Feedback . page 76 Books On Writing Nat Gertler’s Panel Two reviewed . page 77 Conceived by Nuts & Bolts Department DANNY FINGEROTH Script to Pencils to Finished Art: BATMAN #616 Editor in Chief Pages from “Hush,” Chapter 9 by Jeph Loeb, Jim Lee & Scott Williams . page 16 Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN #167 Designer Pages from “The Blind, Part Two” by Benjamin Raab, Rich Burchett and Rodney Ramos . page 26 CHRISTOPHER DAY Script to Thumbnails to Printed Comic: Transcriber SUPERMAN ADVENTURES #40 STEVEN TICE Pages from “Old Wounds,” by Dan Slott, Ty Templeton, Michael Avon Oeming, Neil Vokes, and Terry Austin . page 36 Publisher JOHN MORROW Script to Finished Art: AMERICAN SPLENDOR Pages from “Payback” by Harvey Pekar and Dean Hapiel. page 40 COVER Script to Printed Comic 2: GRENDEL: DEVIL CHILD #1 Penciled by TOMMY CASTILLO Pages from “Full of Sound and Fury” by Diana Schutz, Tim Sale Inked by RODNEY RAMOS and Teddy Kristiansen . -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Graphic Novel Titles

Comics & Libraries : A No-Fear Graphic Novel Reader's Advisory Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives February 2017 Beginning Readers Series Toon Books Phonics Comics My First Graphic Novel School Age Titles • Babymouse – Jennifer & Matthew Holm • Squish – Jennifer & Matthew Holm School Age Titles – TV • Disney Fairies • Adventure Time • My Little Pony • Power Rangers • Winx Club • Pokemon • Avatar, the Last Airbender • Ben 10 School Age Titles Smile Giants Beware Bone : Out from Boneville Big Nate Out Loud Amulet The Babysitters Club Bird Boy Aw Yeah Comics Phoebe and Her Unicorn A Wrinkle in Time School Age – Non-Fiction Jay-Z, Hip Hop Icon Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain The Donner Party The Secret Lives of Plants Bud : the 1st Dog to Cross the United States Zombies and Forces and Motion School Age – Science Titles Graphic Library series Science Comics Popular Adaptations The Lightning Thief – Rick Riordan The Red Pyramid – Rick Riordan The Recruit – Robert Muchamore The Nature of Wonder – Frank Beddor The Graveyard Book – Neil Gaiman Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Ransom Riggs House of Night – P.C. Cast Vampire Academy – Richelle Mead Legend – Marie Lu Uglies – Scott Westerfeld Graphic Biographies Maus / Art Spiegelman Anne Frank : the Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography Johnny Cash : I See a Darkness Peanut – Ayun Halliday and Paul Hope Persepolis / Marjane Satrapi Tomboy / Liz Prince My Friend Dahmer / Derf Backderf Yummy : The Last Days of a Southside Shorty -

How the Dark Horse Came in Portland State University Library Acquires Dark Horse Comics Archives

Michael Bowman, Cristine N. Paschild, and Kimberly Willson-St. Clair How the dark horse came in Portland State University Library acquires Dark Horse Comics archives t’s another hot night, dry and windless. The the general Portland State Library collection, Ikind that makes people do sweaty, secret is available to more than 26,000 students at things. I wait and listen. For a while it’s quiet Portland State University as well as more than as it gets in Sin City.”1 200,000 students and faculty in Oregon and In 2008, the Portland State University Washington through the Orbis Cascade Alli- Library acquired the archives from the third ance academic library consortium. National largest comics publisher in the United States, and international access via the Portland the Milwaukie, Oregon-based State Library’s interlibrary loan Dark Horse Comics, Inc. Port- service also is available to in- land State University alumnus terested readers. Mike Richardson, founder University Librarian Helen and president of Dark Horse H. Spalding states, “This col- Comics, Inc., and Neil Hanker- lection will be a destination son, executive vice president, resource for researchers in donated multiple copies of popular culture, gender stud- all publications and products ies, communications, and generated by Dark Horse from sequential art. Even the busi- its establishment in 1986 to ness and publishing programs the present and will continue will have products, packaging, to provide copies of all future and advertising materials to items produced by the com- study.”4 pany.2 Richardson’s hour-long To date, more than 2,000 presentation covers the history Dark Horse Comics® and the Dark Horse comics, graphic of comics from format changes Dark Horse logo are trade- novels, manga and books have to the Comics Code to the marks of Dark Horse Com- been received, cataloged, and advent of art comics and the ics, Inc., registered in various made available for students graphic novel.3 categories and countries. -

Reframing Comics' Crucial Decade (Proposals Due 1/31/2018)

H-Announce CFP: The Other 1980s: Reframing Comics' Crucial Decade (proposals due 1/31/2018) Announcement published by Brannon Costello on Wednesday, November 29, 2017 Type: Call for Papers Date: January 31, 2018 Subject Fields: Literature, Humanities, American History / Studies, Art, Art History & Visual Studies, Cultural History / Studies CFP: Edited Collection (Proposals due 1/31/2018) The Other 1980s: Reframing Comics’ Crucial Decade Editors: Brannon Costello and Brian Cremins Description: You know the story: it’s 1986 and publications including theNew York Times and Rolling Stone herald the newfound sophistication of a narrative form with its roots in the Depression. “In recent years,” writes Mikal Gilmore in a profile ofBatman: The Dark Knight creator Frank Miller, “the comic-book field has undergone perhaps the most wide-ranging and meaningful creative explosion of its fifty-year-plus history, spawning a new generation of storytellers who are among the more intriguing literary and graphic craftsmen of our day.” In addition to Miller, Gilmore praises the work of Howard Chaykin, the Hernandez Brothers, Alan Moore, and Art Spiegelman. In the closing paragraph of the article, Miller resists any easy categorizations of this new generation of writers and artists. After all, he remarks, “it’s such a big form, and such an endless field, that right now there’s no reason for any comics artist to be bound by any one definition.” The scholarship on this watershed moment in the history of U. S. comics, however, remains limited. If the artists of the period were not “bound by any one definition,” why keep telling the same story that Gilmore first outlined over three decades ago? We invite abstracts for essays that shift our focus to forgotten and neglected comics and graphic narratives of the 1980s published for the English-speaking market in North America and the UK. -

Representation of the Mother's Body As a Narrative Conduit for Wartime

Portland State University PDXScholar Student Research Symposium Student Research Symposium 2015 May 12th, 9:00 AM - 10:30 AM Representation of the Mother’s Body as a Narrative Conduit for Wartime Themes in Saga Bess Pallares Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/studentsymposium Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Rhetoric and Composition Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Pallares, Bess, "Representation of the Mother’s Body as a Narrative Conduit for Wartime Themes in Saga" (2015). Student Research Symposium. 4. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/studentsymposium/2015/Presentations/4 This Oral Presentation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Symposium by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pallares 1 Bess Pallares Professor Kirtley Comics Theory and History 16 March 2015 Representation of the Mother’s Body as a Narrative Conduit for Wartime Themes in Saga From its first panel, the comics series Saga is a narrative that heavily integrates themes of motherhood. Within the first few pages, readers witness the birth of the book’s main character, Hazel, and the transformation of Alana into her mother. But moving beyond the initial moment of creation that launches the narrative, the story of Saga—which dances on the edge of a galaxy- spanning, genocidal war—employs motherhood as a conduit for wartime themes of interdependence and transgenerational memory. -

Sin City: Hard Goodbye V

SIN CITY: HARD GOODBYE V. 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frank Miller | 208 pages | 02 Nov 2010 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781593072933 | English | Milwaukie, United States Sin City: Hard Goodbye v. 1 PDF Book Add a review Your Rating: Your Comment:. Frank Miller. Marv looks like just a twisted, flat copy of Batman - the Batman Miller wanted to write, the Batman he's finally fully realized years later in Holy Terror: [Put a pointy cowl on the guy and give him a giant penny] Are there people in the world like Marv? During this time, a serial killer is on the loose in Sin City who preys on prostitutes and eats them. Marv is taking medications to keep his anger and his killing impulses under control, but his efforts to become a better person are sabotaged when he wakes up from a drunken stupor to find Goldie, his gorgeous one-night-stand, dead beside him. They approach Roark's home and confront him about the murders and his cannibalistic actions. Also, many people seem him as sexist, racist, and there may be some evidence for that. Syllabi and concrete examples of classroom practices have been included by each chapter author. Jun 08, Algernon Darth Anyan rated it really liked it Shelves: , comics. And absolutely zero stars for Frank Miller's rabid personality , xenophobia, and general pigheadedness. Sin City is the place — tough as leather and dry as tinder. I am so glad that I am finally reading this. Marv is able to escape the cops but not before he forces their leader to reveal Roark's name. -

Asfacts Oct19.Pub

doon in 2008. His final story, “Save Yourself,” will be published by BBC Books later this year. SF writers in- Winners for the Hugo Awards and for the John W. cluding Charlie Jane Anders, Paul Cornell, and Neil Campbell Award for Best New Writer were announced Gaiman have cited his books as an important influence. August 18 by Dublin 2019, the 77th Worldcon, in Dub- Dicks also wrote over 150 titles for children, including lin, Ireland. They include a couple of Bubonicon friends the Star Quest trilogy, The Baker Street Irregulars series, – Mary Robinette Kowal, Charles Vess, Gardner Dozois, and The Unexplained series, plus children’s non-fiction. and Becky Chambers. The list follows: Terrance William Dicks was born April 14, 1935, in BEST NOVEL: The Calculating Stars by Mary Robi- East Ham, London. He studied at Downing College, nette Kowal, BEST NOVELLA: Artificial Condition by Cambridge and joined the Royal Fusiliers after gradua- Martha Wells, BEST NOVELETTE: “If at First You Don’t tion. He worked as an advertising copywriter until his Succeed, Try, Try Again” by Zen Cho, BEST SHORT STO- mentor Malcolm Hulke brought him in to write for The RY: “A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendi- Avengers in the ’60s, and he wrote for radio and TV be- um of Portal Fantasies” by Alix E. Harrow, BEST SERIES: fore joining the Doctor Who team in the late ’60s. He Wayfarers by Becky Chambers, BEST GRAPHIC STORY: also worked as a producer on various BBC programs. He Monstress, Vol 3: Haven by Marjorie Liu and illustrated is survived by wife Elsa Germaney (married 1963), three by Sana Takeda, sons, and two granddaughters. -

Comic Book Club Handbook

COMIC BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for comics and graphic novels! STAFF COMIC BOOK LEGAL Charles Brownstein, Executive Director Alex Cox, Deputy Director DEFENSE FUND Samantha Johns, Development Manager Kate Jones, Office Manager Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Betsy Gomez, Editorial Director protecting the freedom to read comics! Our work protects Maren Williams, Contributing Editor readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor tors who face the threat of censorship. We monitor legislation Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. BOARD OF DIRECTORS We create resources that promote understanding of com- Larry Marder, President ics and the rights our community is guaranteed. Every day, Milton Griepp, Vice President Jeff Abraham, Treasurer we publish news and information about censorship events Dale Cendali, Secretary as they happen. We are partners in the Kids’ Right to Read Jennifer L. Holm Project and Banned Books Week. Our expert legal team is Reginald Hudlin Katherine Keller available at a moment’s notice to respond to First Amend- Paul Levitz ment emergencies. CBLDF is a lean organization that works Andrew McIntire hard to protect the rights that our community depends on. For Christina Merkler Chris Powell more information, visit www.cbldf.org Jeff Smith ADVISORY BOARD Neil Gaiman & Denis Kitchen, Co-Chairs CBLDF’s important Susan Alston work is made possible Matt Groening by our members! Chip Kidd Jim Lee Frenchy Lunning Join the fight today! Frank Miller Louise Nemschoff http://cbldf.myshopify Mike Richardson .com/collections William Schanes José Villarrubia /memberships Bob Wayne Peter Welch CREDITS CBLDF thanks our Guardian Members: Betsy Gomez, Designer and Editor James Wood Bailey, Grant Geissman, Philip Harvey, Joseph Cover and interior art by Rick Geary. -

Comic Composition & Ideology

ENGL 3080J, Sec 117 Spring 2015, Ellis 020 Writing and Rhetoric II: Comic Composition & Ideology Instructor: Rachael Ryerson Office: Ellis 307 Hours: MWF 1:00-2:30, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Course Description This course will focus on comic/graphic novel/webcomic composition and rhetoric. To that end, we will be reading comics and critical articles about comics, writing about comics, and creating our own comics. We will read texts created by artists/writers like Art Spiegelman, Brian Vaughn and Fiona Staples, Frank Miller, Sam Keith, Andy and Lana Wachowski, Allison Bechdel, Scott McCloud, and many others, critically analyze comics in terms of ideology and formal composition, and create comics using either digital or material means. This course will also include instruction in online comic generators, comic composing software, and comic design. This course works from two premises: one, comics are socio-cultural artifacts that reflect dominant and subversive ideologies and two, they are complex sites of multimodal meaning making where image, audio (effects), text, spatial organization, and the gestural work in concert to express meaning. With this understanding in mind, we will aim toward development of our rhetorical, multimodal, and cultural literacies through the detailed reading, analysis, and creation of comics. Course Goals & Outcomes Develop cultural, critical literacy by identifying, describing, and analyzing ideological aspects of comics Develop multimodal composition literacy by analyzing and utilizing multiple modes of meaning making Research and write academic, critical arguments about comics Analyze and apply visual, rhetorical principles for an audience Analyze and evaluate the rhetorical successes/failures of comics design Approach composing/designing as a recursive process Required Materials Kieth, Sam and William Messner-Loeb. -

![1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4211/1-over-50-years-of-american-comic-books-hardcover-1904211.webp)

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover] Product details Publisher: Bdd Promotional Book Co Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0792454502 Publication Date: November 1, 1991 A half-century of comic book excitement, color, and fun. The full story of America's liveliest, art form, featuring hundreds of fabulous full-color illustrations. Rare covers, complete pages, panel enlargement The earliest comic books The great superheroes: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and many others "Funny animal" comics Romance, western, jungle and teen comics Those infamous horror and crime comics of the 1950s The great superhero revival of the 1960s New directions, new sophistication in the 1970s, '80s and '90s Inside stories of key Artist, writers, and publishers Chronicles the legendary super heroes, monsters, and caricatures that have told the story of America over the years and the ups and downs of the industry that gave birth to them. This book provides a good general history that is easy to read with lots of colorful pictures. Now, since it was published in 1990, it is a bit dated, but it is still a great overview and history of comic books. Very good condition, dustjacket has a damage on the upper right side. Top and side of the book are discolored. Content completely new 2. Alias the Cat! Product details Publisher: Pantheon Books, New York Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0-375-42431-1 Publication Dates: 2007 Followers of premier underground comics creator Deitch's long career know how hopeless it's been for him to expunge Waldo, the evil blue cat that only he and other deranged characters can see, from his cartooning and his life. -

Grendel Omnibus Volume 2: the Legacy Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GRENDEL OMNIBUS VOLUME 2: THE LEGACY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matt Wagner,Diana Schutz,Tim Sale,Bernie Mireault,The Pander Brothers | 552 pages | 25 Dec 2012 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781595828941 | English | Milwaukie, United States Grendel Omnibus Volume 2: The Legacy PDF Book Not even the last two chapters could was the bad taste away. The Devil Inside. Need another excuse to treat yourself to a new book this week? Thank you! Matt Kindt! Pass it on! Matt Wagner was born on October 9, To ask other readers questions about Grendel Omnibus, Vol. What she finds is a mind-blowing In the Grendel Cycle, the spirit of Grendel is the spirit of violence, passing down through generations, spoiling and corrupting everything around it. Christine Spar, Hunter Rose's grand daughter takes on the mantle of Grendel, becoming the second in line. I absolutely loved the first omnibus and was looking forward to the next volume. I still find that content disturbing, but comparing this second omnibus to the first really makes me appreciate the first more. Devil Child. The Eisner award-winning, surreal superhero series, The Flaming Carrot, returns with a new omnibus collection! Robert Venditti. Imaginary Fiends. In one panel for example, on page , Christine Spars's shoulders are literally 3 times as wide as her waist. Grendel: Devil's Odyssey 4. Here's a summary of confusing plot points: view spoiler [ 1 The whole thing kicks off when Christine's son is abducted and murdered. Product Details. See more details at Online Price Match. Download Hi Res. Pricing policy About our prices.