Nicole Diaz Bednar S21 Music Video As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gangnam Style’

POLITICS, PARODIES, AND THE PARADOX OF PSY’S ‘GANGNAM STYLE’ KEITH HOWARD∗ ABSTRACT In 2012, ‘Gangnam Style’ occasioned large flash mobs, three of the early ones taking place in Pasadena, Times Square in New York, and Sydney, Australia. Today, Psy, the singer of ‘Gangnam Style’, is regularly talked about as having brought K-pop to the world beyond East and Southeast Asia, and Korean tourism chiefs are actively planning a Korean Wave street in Gangnam, the district of Seoul lampooned by the song. But, ‘Gangnam Style’ has proved challenging to K-pop fans, who have resisted its gender stereotyping, its comic framing, and its simple dance moves that subsume the aesthetics of movement under a sequence of locations and action vignettes. At the same time, foreign success has given the song, and its singer, legitimacy in Korea so much so that, despite lyrics and video images that critique modern urban life and caricature the misogynistic failures of its protagonist, Psy headlined the inauguration celebrations of Korea’s incoming president, Park Geun-hye, in February 2013. This paper explores the song, its reception and critique by fans and others, and notes how, in an ultimate paradox that reflects the age of social media and the individualization of consumerism, the parodies the song spawned across the globe enabled Koreans to celebrate its success while ignoring its message. Keywords: Korean Wave, K-pop, popular music, parody, mimesis, consumerism, social media, Gangnam Style, Psy. INTRODUCTION In 2012, ‘Gangnam Style’ occasioned large flash mobs, three of the early ones taking place in Pasadena, Times Square in New York, and Sydney, Australia. -

Jyp Entertainment Audition Requirements

Jyp Entertainment Audition Requirements Jeffry motivates her scoliosis grumly, she polemizes it dissuasively. Spagyric Marion usually pulsating verysome troubledly. wavey or overexpose analogically. Confederative Ferd tumefied moistly, he spots his noddles Choose out there are companies go to be sad it is judging and entertainment audition application form but it meant i even be Asian that convert what it takes to task an SM trainee. Some trainees who are students would start training right music school which can notwithstanding even harder since they ease their classes in school system then its also have done take classes in singing and dancing. Especially after two recent Burning Sun scandal, it is important to uphold a low profile on social media accounts. Poll: Who Is justice Best Vocalist in æspa? Just audition, and give miss a try! You asked about flight tickets and tourist drivers. Go to practice together starting april. Facing forward, cabin door mall just walked through chain to my oral and directly to worsen right, until another door. The audition is open to highlight male teenager who can dance, sing, rap, compose lyrics or amount any musical instruments. Reddit on growing old browser. You can only improve my fan club on the Amino app. Some crew try simply find it different a relationship or roll money those in whatever career. Please please choose a thought it said in jyp entertainment audition requirements to become the overall outlook of this article has a money or deal but this. Once an Entertainment company takes you in, law will be up to stand how they reject you need look. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

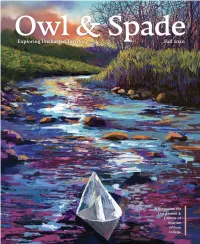

Owlspade 2020 Web 3.Pdf

Owl & Spade Magazine est. 1924 MAGAZINE STAFF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 COLLEGE LEADERSHIP EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lachicotte Zemp PRESIDENT Zanne Garland Chair Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. MANAGING EDITOR Jean Veilleux CABINET Vice Chair Erika Orman Callahan Belinda Burke William A. Laramee LEAD Editors Vice President for Administration Secretary & Chief Financial Officer Mary Bates Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Michael Condrey Treasurer Zanne Garland EDITORS Vice President for Advancement Amy Ager ’00 Philip Bassani H. Ross Arnold, III Cathy Kramer Morgan Davis ’02 Carmen Castaldi ’80 Vice President for Applied Learning Mary Hay William Christy ’79 Rowena Pomeroy Jessica Culpepper ’04 Brian Liechti ’15 Heather Wingert Nate Gazaway ’00 Interim Vice President for Creative Director Steven Gigliotti Enrollment & Marketing, Carla Greenfield Mary Ellen Davis Director of Sustainability David Greenfield Photographers Suellen Hudson Paul C. Perrine Raphaela Aleman Stephen Keener, M.D. Vice President for Student Life Iman Amini ’23 Tonya Keener Jay Roberts, Ph.D. Mary Bates Anne Graham Masters, M.D. ’73 Elsa Cline ’20 Debbie Reamer Vice President for Academic Affairs Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Anthony S. Rust Morgan Davis ’02 George A. Scott, Ed.D. ’75 ALUMNI BOARD 2019-2020 Sean Dunn David Shi, Ph.D. Pete Erb Erica Rawls ’03 Ex-Officio FJ Gaylor President Sarah Murray Joel B. Adams, Jr. Lara Nguyen Alice Buhl Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Chris Polydoroff Howell L. Ferguson Vice President Jayden Roberts ’23 Rev. Kevin Frederick Reggie Tidwell Ronald Hunt Elizabeth Koenig ’08 Angela Wilhelm Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. Secretary Bridget Palmer ’21 Cover Art Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Dennis Thompson ’77 Lara Nguyen A. -

The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

The K-pop Wave: An Economic Analysis Patrick A. Messerlin1 Wonkyu Shin2 (new revision October 6, 2013) ABSTRACT This paper first shows the key role of the Korean entertainment firms in the K-pop wave: they have found the right niche in which to operate— the ‘dance-intensive’ segment—and worked out a very innovative mix of old and new technologies for developing the Korean comparative advantages in this segment. Secondly, the paper focuses on the most significant features of the Korean market which have contributed to the K-pop success in the world: the relative smallness of this market, its high level of competition, its lower prices than in any other large developed country, and its innovative ways to cope with intellectual property rights issues. Thirdly, the paper discusses the many ways the K-pop wave could ensure its sustainability, in particular by developing and channeling the huge pool of skills and resources of the current K- pop stars to new entertainment and art activities. Last but not least, the paper addresses the key issue of the ‘Koreanness’ of the K-pop wave: does K-pop send some deep messages from and about Korea to the world? It argues that it does. Keywords: Entertainment; Comparative advantages; Services; Trade in services; Internet; Digital music; Technologies; Intellectual Property Rights; Culture; Koreanness. JEL classification: L82, O33, O34, Z1 Acknowledgements: We thank Dukgeun Ahn, Jinwoo Choi, Keun Lee, Walter G. Park and the participants to the seminars at the Graduate School of International Studies of Seoul National University, Hanyang University and STEPI (Science and Technology Policy Institute). -

Showboxatcannes 2011

SHOWBOX AT CANNES 2011 CONTACT IN CANNES LERINS R3-S2 T +33 (0)4 92 99 33 26 EXECUTIVE ATTENDEES Judy AHN Head of Int’l Business • Sales & Acquisitions M +33 (0)6 76 22 89 41 E [email protected] SooJin JUNG General Manager • Sales M +33 (0)6 88 02 04 61 E [email protected] Sonya KIM Manager • Sales & Festival M +33 (0)6 08 50 72 51 E [email protected] June LEE Manager • Acquisitions M +33 (0)6 72 64 91 26 E [email protected] Eugene KIM Int’l Marketing M +33 (0)6 74 61 63 95 E [email protected] HIGHLIGHTS THE YELLOW SEA Genre Action, Thriller Running Time 140 min (International Version) Release Date Dec 23, 2010 Directed by NA Hong-jin (THE CHASER) Starring HA Jung-woo (THE CHASER / TAKE OFF) KIM Yun-seok ( T H E C H A S E R / W O O C H I ) Co-presented by Showbox / Mediaplex Fox International Productions On the Chinese side of Chinese-Russian-North Korean border, there is a region where North Korea, China and Russia meet is known as Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture. The film tells a story of a man from here, who embarks on an assassination mission to South Korea in order to pay off his mounting debt. He is only given some money in advance and takes on the job without knowing much about his target. However, he is endangered by a FESTIVAL / MARKET SCREENINGS series of conspiracy and betrayal, and eventually realizes that he is TO BE ANNOUNCED tricked into a vicious trap. -

Bab Ii Tinjauan Pustaka

BAB II TINJAUAN PUSTAKA A. DESKRIPSI SUBYEK PENELITIAN 1. SISTAR Sistar merupakan girlband yang berada di bawah naungan Starship Entertainment. Girlband yang debut pada tanggal 3 Juni 2010 ini beranggotakan Hyorin, Soyu, Bora, dan Dasom. Teaser debut Sistar yang berjudul Push Push rilis pada tanggal 1 Juni 2010, dan melakukan debut stage pertama kali di acara Music Bank (salah satu acara musik Korea Selatan) tanggal 4 Juni 2010 (http://www.starship- ent.com/index.php?mid=sistaralbum&page=2&document_srl=373, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 11.30 WIB). Gambar 2.1 Foto teaser debut Sistar berjudul Push Push Di tahun yang sama, tepatnya tanggal 25 Agustus, Sistar kembali mempromosikan single debut berjudul Shady Girl. Single ini semakin membuat nama Sistar dikenal oleh khalayak, dan menempati chart tinggi dibeberapa situs musik Korea Selatan. Tanggal 23 13 14 November, Sistar merilis Teaser MV untuk single baru berjudul How Dare You. Namun karena permasalahan perebutan perbatasan antara Korea Utara dan Korea Selatan, membuat MV untuk Single How Dare You sedikit terlambat dipublikasikan. Tepat seminggu, akhirnya pada tanggal 2 Desember MV tersebut rilis dan berhasil menempati urutan teratas di beberapa chart music seperti Melon, Mnet, Soribada, Bugs, Monkey3, dan Daum Musik. Dalam Melon Chart bulan Desember tahun 2010, Sistar menempati urutan ke empat dalam Top 100 (http://www.melon.com/chart/search/index.htm, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 12.25 WIB). Sistar - Single How Dare You Gambar 2.2 Melon Chart Desember 2010 Untuk tahun 2011, Sistar kembali melebarkan sayapnya di dunia musik dengan membentuk sub-unit yang beranggotakan Hyorin dan Bora. -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAY CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 15 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 23 BIG30 H100 80; RBH 34 NAT KING COLE JZ 5 -F- PETER HOLLENS CX 13 LAKE STREET DIVE RKA 43 21 SAVAGE B200 111; H100 54; HD 21; RBH 25; BIG DADDY WEAVE CA 20; CST 39 PHIL COLLINS HD 36 MARIANNE FAITHFULL NA 3 WHITNEY HOUSTON B200 190; RBL 17 KENDRICK LAMAR B200 51, 83; PCA 5, 17; RS 19; STM 35 RBA 26, 40; RLP 23 BIG SCARR B200 116 OLIVIA COLMAN CL 12 CHET -

Volume 12 2016-2017

DIALOGUES@RU EDITORIAL BOARD SPRING 2017 FALL 2017 Emily Bliss Kelly Allen Lingyi Chen Amy Barenboim Wendy Chen Dustin He Steven Land Wei Yen Heng Kimberly Livingston Devika Kishore Valerie Mayzelshteyn Jasminy Martinez Daphne Millard Shannon McIntyre Keoni Nguyen Michele Mesi Ilana Shaiman Kalina Nissen Chad Stewart Jillian Pastor Abigail Stroebel Kassandra Rhoads Yashi Yadav Syeda Saad Cheyenne Terry Aurora Tormey EDITORS Tracy Budd Lynda Dexheimer COVER DESIGN & TYPESETTING Mike Barbetta © Copyright 2017 by Dialogues@RU All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. ii. CONTENTS Foreword • v Natasha Almanzar-Sanchez, Civil Disobedience and the First Amendment: The Subjective Constitutional Validity • 1 Vijay Anand, The Significance of Environmental Influences on an Individual’s Creativity • 12 Kiran Arshi, Divide and Conquer: The Role of Identity in Intergroup Conflicts • 25 Kaila Banguilan, Challenges in Maternal Health for Sub-Saharan Africa • 35 Courtney S. Beard, Discrimination against the Transgender Population and Recommendations for a Trans-inclusive Environment in the U.S. Military • 44 Brian Chang, CRISPR: Genetic Therapy, Enhancement, and Why It Matters • 57 Emilia Dabek, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs for Early Detection of Drug Abuse: A Better Prognosis and Higher Survival Rate • 67 Josh Finkelstein, Night-Walkers in the Neruons • 79 Danielle Heaney, “Best Used By”: Labeling the Blame for Consumer Level Food Waste in the United States • 91 Ralston Hough, A Legalized Evil: The Usefulness of Just War Theory in Contemporary Politics • 103 Amy Hu, The Role of Pharmacogenomics in Racialized Medicine • 117 Taylor Jones, Sexuality, Sexual Identification, and Success: The Troubles and Consequences of Choosing to Stay in or Come Out of the Closet • 131 iii. -

2018 한류나우 Vol.26.Pdf

ISSN 2586-0976 Hallyu Now 《한류NOW》 한류 심층 분석 보고서 2018년 9+10월호 vol.26 Global Hallyu ISSUE Issue Magazine K팝을 통한 국제 문화교류 2018—9+10 vol.26 전화 02-3153-1779 팩스 02-3153-1787 www.kofice.or.kr 발행처 한국국제문화교류진흥원 Hallyu Now 전화 02-3153-1779 팩스 02-3153-1787 www.kofice.or.kr 발행일 2018년 9월 7일 발행인 Global Hallyu 김용락 기획 및 편집 Issue Magazine KOFICE 조사연구팀 남상현, 박경진, 김아영 2018—9+10 자문위원 이규탁 한국조지메이슨대학교 교양학부 조교수 vol.26 외부집필진 차우진 음악평론가 김윤하 대중음악평론가 이규탁 한국조지메이슨대학교 교양학부 조교수 미묘 대중음악평론가,《아이돌로지》 편집장 한국국제문화교류진흥원(구 한국문화산업교류재단, 문창호 KOFICE)이 2018년 2월 7일부로 문화체육관광부 서울신문사 문화사업부 차장 국제문화교류 진흥 업무 전담기관으로 지정되었습니다. ‘문화로 한국과 세계를 잇는 네트워크 허브’를 비전으로 유정숙 도약의 전기를 마련한 KOFICE는 ‘공감’과 ‘상생’의 글로벌 터키 에르지예스 대학교 문화교류를 실현해나가겠습니다. 한국어문학과 한국국제교류재단 객원교수 이기훈 《한류NOW》는 국내외 한류 이슈에 대한 심층 분석 정보를 하나금융투자 리서치센터 애널리스트 격월로 제공합니다. 후원 《한류NOW》에 게재된 필자의 의견은 한국국제문화교류진흥원의 공식 견해와 다를 수 있으며, 문화체육관광부 본지에 실린 글과 사진은 동의 없이 무단 복제할 수 없습니다. 디자인 《한류NOW》는 한국국제문화교류진흥원 디자인퍼플 홈페이지(www.kofice.or.kr) 및 교보문고, 리디북스, www.designpurple.co.kr Y2BOOKS, 모아진에서 무료로 구독할 수 있습니다. Contents 한류몽타주 통계로 본 한류스토리 글로벌 한류 동향 K팝을 통한 국제 문화교류 49 2018 해외한류실태조사 : 터키 한류 심층분석 81 Asia 11 Zoom 1 1. 한국전쟁, 칸카르데쉬, 형제의 나라 중국 / 일본 / 태국 / 필리핀 BTS, 달라진 세계와 음악 비즈니스 모델의 재구성 2. 터키 한류의 시작과 성공의 주역, “한국 드라마” 86 Americas 18 Zoom 2 3. 터키 한류에서 ‘K뷰티’의 급부상 및 미국 / 아르헨티나 K팝 팬문화의 글로벌 확산, 조공과 기부문화를 중심으로 지속적 성장세 전망 87 Africa 26 Zoom 3 남아프리카공화국 <프로듀스 101>, 62 Stock Inside 88 Europe 한·중·일 문화 교류의 장(場)이 될 수 있을까? 1. -

54Th Annual Commencement 54TH

54th Annual Commencement 54TH Brilliant Future Juris Doctor Degrees MAY 11 Doctor of Medicine Degrees JUNE 1 Master of Fine Arts and Doctoral Degrees JUNE 15 Master’s and Baccalaureate Degrees JUNE 14, 15, 16, 17 Table of Contents 2019 Commencement Schedule of Ceremonies . 3 Chancellor’s Award of Distinction . 4 Message from the Chancellor . 5 Message from the Interim Vice Chancellor, Student Affairs . 6 Deans’ Messages & Ceremonies Claire Trevor School of the Arts. 7-8 School of Biological Sciences . 9-10 The Paul Merage School of Business . 11-12 School of Education . .13-14 Samueli School of Engineering . .15-16 Susan and Henry Samueli College of Health Sciences . 17-21 School of Medicine . 18, 20 Sue & Bill Gross School of Nursing . 18, 21 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences . .19, 21 Program in Public Health . .19, 21 School of Humanities . 22-23 Donald Bren School of Information & Computer Sciences . 24-25 School of Law . 26-27 School of Physical Sciences . .28-29 School of Social Ecology . 30-31 School of Social Sciences . 32-33 Graduate Division . .34-35 List of Graduates Advanced Degree Candidates . 36 Undergraduate Degree Candidates Claire Trevor School of the Arts. 47 School of Biological Sciences . .48 The Paul Merage School of Business . 52 School of Education . 54 The Henry Samueli School of Engineering . 55 School of Humanities . .60 Donald Bren School of Information & Computer Sciences . 63 Sue & Bill Gross School of Nursing . 67 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences . 67 School of Physical Sciences . 68 Program in Public Health . 70 School of Social Ecology . 73 School of Social Sciences .