~Ht Ijfctoria Jnstitute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age Key Sites Southeast Wales – Neolithic

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Key Sites, Southeast Wales, 22/12/2003 Neolithic and earlier Bronze Age Key Sites Southeast Wales – Neolithic and early Bronze Age 22/12/2003 Neolithic Domestic COED-Y-CWMDDA Enclosure with evidence for flint-working Owen-John 1988 CEFN GLAS (SN932024) Late Neolithic hut floor dated to 4110-70 BP. Late Neolithic flints have been found at this site. Excavated 1973 Unpublished: see Grimes 1984 PEN-Y-BONT, OGMORE (SS863756) Pottery, hearth and flints Hamilton and Aldhouse-Green 1998; 1999; Gibson 1998 MOUNT PLEASANT, NEWTON NOTTAGE (SS83387985) Hut, hearth, pottery Savory 1952; RCAHMW 1976a CEFN CILSANWS HUT SITE (SO02480995) Hut consisting of 46 stake holes found under cairn. The hut contained fragments of Mortlake style Peterborough Ware and flint flakes Webley 1958; RCAHMW 1997 CEFN BRYN 10 (GREAT CARN) SAM Gml96 (SS49029055) Trench, pit, posthole and hearth associated with Peterborough ware and worked flint; found under cairn. Ward 1987 Funerary and ritual CEFN BRYN BURIAL CHAMBER (NICHOLASTON) SAM Gml67 (SS50758881) Partly excavated chambered tomb, with an orthostatic chamber surviving in a roughly central position in what remains of a long mound. The mound was made up peaty soil and stone fragments, and no trace of an entrance passage was found. The chamber had been robbed at some time before the excavation. Williams 1940, 178-81 CEFN DRUM CHAMBERED TOMB (SN61360453,) Discovered during the course of the excavation of a deserted medieval settlement on Cefn Drum. A pear-shaped chamber of coursed rubble construction, with an attached orthostatic passage ending in a pit in the mouth of a hornwork and containing cremated bone and charcoal, were identified within the remains of a mound with some stone kerbing. -

Great Carn Cefn Bryn

Great Archaeological Sites in Swansea 3. THE GREAT CARN ON CEFN BRYN The Gower peninsula seems to have occupied a special place in the spirituality of Neolithic and Bronze Age people. Although it is only 20km long by 12km at its widest point, it contains six Neolithic chambered tombs, clustered around Rhossili Down and Cefn Bryn. Although chambered tombs were no longer used for burial after the Late Neolithic, the places where they had been built continued to be a focus for centuries afterwards, with large numbers of Bronze Age cairns constructed on both Rhossili Down and Cefn Bryn. There has never been any proper archaeological excavation of the cairns on Rhossili Down, but some of those on Cefn Bryn were examined by Swansea University in the 1970s and 1980s. The structure known as the Great Carn (SS 4903 9056) is one of these. It stands only 100m from the chambered tomb known as Arthur’s Stone or Maen Ceti. Although it is much less showy – just a low, flattish mound made of lumps of the local conglomerate rock – it is still impressive, and at 20m across it is the largest cairn on the ridge, hence its name. The excavators found that the heap of stones concealed a ring of boulders 12m across. It was not clear at what stage in the cairn’s construction this ring was laid out, whether it was the first thing to be constructed before it was filled in with stone inside and outside, or whether it had originally been intended as an outside kerb. -

NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA39 GOWER © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 Penrhyn G ŵyr – Disgrifiad cryno Mae Penrhyn G ŵyr yn ymestyn i’r môr o ymyl gorllewinol ardal drefol ehangach Abertawe. Golyga ei ddaeareg fod ynddo amrywiaeth ysblennydd o olygfeydd o fewn ardal gymharol fechan, o olygfeydd carreg galch Pen Pyrrod, Three Cliffs Bay ac Oxwich Bay yng nglannau’r de i halwyndiroedd a thwyni tywod y gogledd. Mae trumiau tywodfaen yn nodweddu asgwrn cefn y penrhyn, gan gynnwys y man uchaf, Cefn Bryn: a cheir yno diroedd comin eang. Canlyniad y golygfeydd eithriadol a’r traethau tywodlyd, euraidd wrth droed y clogwyni yw bod yr ardal yn denu ymwelwyr yn eu miloedd. Gall y priffyrdd fod yn brysur, wrth i bobl heidio at y traethau mwyaf golygfaol. Mae pwysau twristiaeth wedi newid y cymeriad diwylliannol. Dyma’r AHNE gyntaf a ddynodwyd yn y Deyrnas Unedig ym 1956, ac y mae’r glannau wedi’u dynodi’n Arfordir Treftadaeth, hefyd. www.naturalresources.wales NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11 Erys yr ardal yn un wledig iawn. Mae’r trumiau’n ffurfio cyfres o rostiroedd uchel, graddol, agored. Rheng y bryniau ceir tirwedd amaethyddol gymysg, yn amrywio o borfeydd bychain â gwrychoedd uchel i gaeau mwy, agored. Yn rhai mannau mae’r hen batrymau caeau lleiniog yn parhau, gyda thirwedd “Vile” Rhosili yn oroesiad eithriadol. Ar lannau mwy agored y gorllewin, ac ar dir uwch, mae traddodiad cloddiau pridd a charreg yn parhau, sy’n nodweddiadol o ardaloedd lle bo coed yn brin. Nodwedd hynod yw’r gyfres o ddyffrynnoedd bychain, serth, sy’n aml yn goediog, sydd â’u nentydd yn aberu ar hyd glannau’r de. -

The Edinburgh Gazette, July 10, 1934. Wales

596 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, JULY 10, 1934. WALES. Monument. County. Parish. Barclodiad-y-gawres Burial Chamber, Llan- Anglesey Llangwyfan. gwyfan. Holyhead, Roman wall surrounding churchyard Holyhead Urban. of St. Cybi's Church, Aberyscir Mound Brecknockshire Aberyscir. Brecon Castle St. John the Evangelist. Builth Castle Builth. Trecastle " Castle Tump " and Bailey Traian mawr. Turpil Stone, Glan-Usk Park, Llangattock Llangattock. Victorinus Stone, Scethrog Llangasty Tal-y-llyn. Castell Flemish (intrenchments), Caron-is-clawdd Cardiganshire .. Caron-is-clawdd. Castell Grogwynion, Llanafan Llanafan. Hirnant, stone circle 220 yards N. of, Melindwr Melindwr. To men Llanio, Llanio Llanio. Castell y Gaer (camp), Merthyr Carmarthenshire Merthyr. Craig Gwytheyrn (camp), Llanfihangel-ar-arth Llanfihangel-ar-arth. Dol-Wilym Burial Chamber, Llanboidy Llanboidy. Domen Llawddog (or Tomen Maesllan) Penboyr Penboyr. Domen Seba (or y Domen Fawr), Penboyr Dryslwn Castle, Llangathen Llangathen. Hirfaen Standing Stone, Llanycrwys Llanycrwys. Napps Camp, Pendine Pendine. Newchurch, Garn Fawr Earth Circle ... Newchurch. Bont Newydd Burial Cave, Cefn (St. Asaph) ... Denbighshire Cefn (St. Asaph). Cadwgan Hall Mound, Esclusham Below Esclusham Below. Castell Cawr Camp (hill fort), Abergele Rural ... Abergele Rural. Castell y Waun (castle mound), Chirk Chirk. Cefn Burial Cave, Cefn (St. Asaph) Cefn (St. Asaph). y Gardden Camp (hill fort), Ruabon Ruabon. Llwyn Bryn-Dinas Camp (hill fort), Llanrhaiadr- Llanrhaiadr-ym-Mochnant :. ym-Mochnant. Llangedwyn. Maes Gwyn Mound, Pentre-Foelas Pentre-Foelas. Mynydd Bach Camp (hill fort), Llanarmon- Llanarmon-Dyftryn-Ceiriog. Dyffryn-Ceiriog. Rhos Ddigre Burial Caves, Llanarmon-yn-Ial ... Llanarmon-yn-Ial. Tomen Cefn Glaniwrch (castle mound), Llanr- Llanrhaiadr-ym-Mochnant.. haiadr-ym-Mochnant. Tomen y Faerdre (castle mound), Glan Tanat, Llanrhaiadr-ym-Mochnant. -

Eboot - September 2014

eBoot - September 2014 This month’s edition includes: • Coach trip • Walking for Health outreach project • Notices • Forthcoming walks • Commercial corner Trip to the northern Dales - June 6th to 12th 2015 6 days walking in Northern Dales based on Graham Hoyle’s walks, to see the Dales at the peak of their spring glory. June 6th to 10th based in Hawes (Walks start at Hardraw Old School Bunkhouse, but participants are free to arrange alternative accommodation in the area) June 10-12th based in Grinton (Walks start at Dales Bike Centre, Fremington, but again can arrange own alternative accommodation. Walks range from 9-11 miles, but can be shortened by using public transport near half way point. Contact Margrid Schindler on 01179747193 or mobile 07910963282 Coach trip Places are still available on the coach trip to Gower on Sunday, 14 September. Tickets are available at the bargain price of £13 for those booking in advance: contact [email protected]. There will be a choice of three walks, each of which features a spectacular section of the southern Gower coast path. We shall see beautiful beaches and some of the finest coastal scenery within a day’s drive of Bristol. All the walks finish by rounding Mumbles Head shortly before meeting up with the coach. The 15 mile A walk will be led by Nigel Andrews and starts from Oxwich and heads north to ascend the low ridge of Cefn Bryn from where there should be good views of both coasts. We then head south-eastwards to Threecliff Bay with the distinctive rocks from which it gets its name before following the beautiful coast path all the way to Mumbles. -

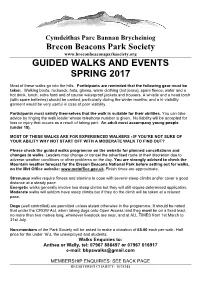

Guided Walks and Events Spring 2017

Cymdeithas Parc Bannau Brycheiniog Brecon Beacons Park Society www.breconbeaconsparksociety.org GUIDED WALKS AND EVENTS SPRING 2017 Most of these walks go into the hills. Participants are reminded that the following gear must be taken. Walking boots, rucksack, hats, gloves, warm clothing (not jeans), spare fleece, water and a hot drink, lunch, extra food and of course waterproof jackets and trousers. A whistle and a head torch (with spare batteries) should be carried, particularly during the winter months, and a hi-visibility garment would be very useful in case of poor visibility. Participants must satisfy themselves that the walk is suitable for their abilities. You can take advice by ringing the walk leader whose telephone number is given. No liability will be accepted for loss or injury that occurs as a result of taking part. An adult must accompany young people (under 18). MOST OF THESE WALKS ARE FOR EXPERIENCED WALKERS - IF YOU’RE NOT SURE OF YOUR ABILITY WHY NOT START OFF WITH A MODERATE WALK TO FIND OUT? Please check the guided walks programme on the website for planned cancellations and changes to walks. Leaders may change or cancel the advertised route at their discretion due to adverse weather conditions or other problems on the day. You are strongly advised to check the Mountain weather forecast for the Brecon Beacons National Park before setting out for walks, on the Met Office website: www.metoffice.gov.uk. Finish times are approximate. Strenuous walks require fitness and stamina to cope with several steep climbs and/or cover a good distance at a steady pace. -

Comic Barclodiad Y Gawres

Syniadau o’r Oes Neolithig blynyddoedd CC blynyddoedd OC Oes y Cerrig Yr Oes Efydd Oes yr 0 Haearn 4000 BC 3000 BC 2000 BC 1000 BC y Rhufeiniaid ym Mhrydain I Oes i yr Ia^ Barclodiad y gawres HEDDIW BYG_Comic_Welsh.indd 1 13/07/2015 10:52 Mae Barclodiad y Gawres yn fedd cyntedd ar yr A4080 rhwng Aberffraw a Rhosneigr. Mae traeth gerllaw'r safle a digon o le parcio i ffwrdd o'r ffordd. Gallwch gyrraedd y safle drwy gerdded am ychydig funudau ar lwybr eithaf rhwydd. Llybr Arfordir I Rhosneigr Ynys Môn Siambr Gladdu Barclodiad y Gawres A4080 I Aberffraw Porth trecastell 5o medr Ysgrifennwyd a darluniwyd gan John G. Swogger Golygydd y gyfres Marion Blockley Cynhyrchwyd gan Blockley Design Cyhoeddwyd gan Cadw c 2Oi5 Cyfieithiwyd gan Alun Gruffydd – Bla Translation Cadw: Plas Carew, Uned 5/7 Cefn Coed, Parc Nantgarw, Caerdydd CF15 7QQ BYG_Comic_Welsh.indd 2 13/07/2015 10:52 Barclodiad y GawresSyniadau o’r Oes Ar arfordir gorllewinol Ynys Môn, Neolithig ar benrhyn creigiog yn wynebu'r môr, mae tomen o bridd. Mae'n amlwg uwchben y traeth, lle mae pobl yn chwarae yn y tywod, yn nofio ac yn syrffio a physgota. Mae rhai o'r cerrig hyn wedi eu Os edrychwch y tu mewn i'r naddu â ffurfiau igam-ogam, domen, fe welwch gerrig yn cylchoedd a deiamwnt. sefyll yn fertigol mewn cylch... gyda charreg wastad lawer iawn mwy yn gorwedd ar eu pennau. Pysgod? Llysywod? Llyffantod? Mae'n swnio fel gweddillion un o fy mhrydau bwyd i! Daeth archaeolegwyr o hyd i rai esgyrn dynol wedi llosgi yn y siambrau ochr. -

Copyrighted Material

26_595407 bindex.qxd 8/29/05 8:56 PM Page 770 Index Alfred’s Tower (Stourhead), 402 Lavenham, 570 Abbey, The, (Bury St. Alfriston, 324–329 London, 210–211 Edmunds), 566 Alhambra Theatre (Bradford), Manchester, 619 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 688 Norwich, 582 448–449 Alice’s Shop (Oxford), 266 St. Albans, 275 Abbey Theatre (St. Albans), 275 All Saints (London), 212 Stow-on-the-Wold, 485 Abbey Treasure Museum Althorp, 586 Stratford-upon-Avon, 508 (London), 171 Alum Bay (Isle of Wight), 350 Windsor, 242 Abbot Hall Art Gallery (Kendal), The Amateur Dramatic Club Woburn, 278 644 (Cambridge), 559 Apple Market (London), 214 Aberconwy House (Conwy), 764 Ambleside, 651–654 Apsley House, The Wellington Abergavenny, 724–727 American Bar (London), 227–228 Museum (London), 184, 186 Abergavenny Castle, 726 American Express Aquarium of the Lakes Abergavenny Museum, 726 Cardiff, 713 (Lakeside), 649 Aberystwyth Musical Festival, London, 113 Arboretum Sensory Trail, 13 45–46 traveler’s checks, 39 Arbour Antiques (Stratford- Accommodations The American Museum (Bath), upon-Avon), 508 best, 14–17 385 Architecture, 23–30 surfing for, 55–56 The American Museum books about, 85 tips on, 76–80 (Claverton), 8 Arlington Row (Bibury), 475 Acorn Bank Garden & Watermill Amgueddfa Llandudno Armouries (London), 167 (Penrith), 667–668 Museum, 769 Arnolfini Portrait, 176 Adam and Eve (Norwich), 583 Ampleforth Abbey, 695 Aromatherapy, 81 Adam & Eve Tavern (Lincoln), Anchor (Cambridge), 559 Art, 20–23 605 Andrew Lamputt (Hereford), books about, 85 Addison’s Walk (Oxford), 262 531 Art galleries, Lincoln, 607 Admiral Duncan (London), 226 Angel Tavern (Cardiff), 724 The Art Gallery (Scarborough), Afternoon tea, 11 Anglesey, Isle of, 758–761 698 Ain’t Nothing But Blues Bar Anne Hathaway’s Cottage Arthur’s Stone, 737 (London), 222 (Stratford-upon-Avon), 504 Arts and crafts. -

Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust

THE GLAMORGAN-GWENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST Recently excavated medieval ship at Newport Half-yearly review October 2002 & Annual review of Cadw projects 2001-2002 Registered in Wales No. 1276976. Registered Office Heathfield House, Heathfield Swansea A Company limited by Guarantee without Share Capital. The Trust is a Registered Charity No 505609 Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust Ltd Half-Yearly Review September 2002 Contents Page REVIEW OF CADW PROJECTS APRIL 2001 – MARCH 2002 3 CURATORIAL PROJECTS GGAT 1 Regional Heritage Management Services 3 GGAT 43 Regional Archaeological Planning Services 11 GGAT 67 Tir Gofal 13 THREAT-LED ASSESSMENTS GGAT 61 Historic Landscape Characterisation – Merthyr Tydfil 14 GGAT 63 Lowland Romano-British Settlements 19 GGAT 65 Deserted Rural Settlements 19 GGAT 66 Prehistoric Non-defensive Sites 21 GGAT 72 Prehistoric, Funerary and Ritual Sites 22 GGAT 73 Early Medieval Ecclesiastical Settlement 24 REVIEW OF CADW PROJECTS APRIL 2002 – SEPT 2002 25 CURATORIAL PROJECTS GGAT 67 Tir Gofal 25 GGAT 74 Research Agenda in Wales 26 THREAT-LED ASSESSMENTS GGAT 61 Historic Landscape Characterisation – Merthyr Mawr, Kenfig and Margam Burrows and Margam Mountain 26 GGAT 66 Prehistoric Non-defensive Sites 27 GGAT 72 Prehistoric, Funerary and Ritual Sites 28 GGAT 73 Early Medieval Ecclesiastical Settlement 28 GGAT 75 Roman Vici and Roads 29 CADW-FUNDED SCIENTIFIC CONTRACTS 29 POST-EXCAVATION AND PUBLICATION REVIEW 30 Grey Literature 31 FUTURE PROGRAMME OCTOBER 2002-MARCH 2003 33 CURATORIAL PROJECTS GGAT 1 Regional Heritage -

An Investigation Into Prior Activity at Neolithic Monuments in Britain

Durham E-Theses Windows into the past: an investigation into prior activity at Neolithic monuments in Britain GRAF, JANICE,CAROL How to cite: GRAF, JANICE,CAROL (2012) Windows into the past: an investigation into prior activity at Neolithic monuments in Britain, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3510/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Windows into the past: an investigation into prior activity at Neolithic monuments in Britain Janice Carol Graf Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD Department of Archaeology University of Durham 2011 i Abstract Windows into the past: an investigation into prior activity at Neolithic monuments in Britain Janice Graf This thesis investigates the nature of the buried ground surfaces beneath Neolithic long barrows and chambered tombs in Britain. Excavations at sites across the country have revealed the presence of pre-mound pits, postholes and artefact scatters on the preserved ground surfaces below the monuments, suggesting episodes of earlier human activity. -

Landscape Character Area X

BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT AUGUST 2012 PREPARED BY FIONA FYFE ASSOCIATES WITH COUNTRYSCAPE, ALISON FARMER ASSOCIATES AND JULIE MARTIN ASSOCIATES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Landscape Character Assessment was commissioned by the Brecon Beacons National Park Authority in March 2012. It has been prepared by Fiona Fyfe Associates, with Julie Martin Associates, Alison Farmer Associates and Countryscape, between March and August 2012. The spatial approach of the Landscape Character Assessment provides a clear geographic reference for landscape character, special qualities and issues of landscape change across the National Park. It is intended for use in a number of ways, including: Assessing the qualities of wildness, tranquillity and remoteness across the National Park to develop a policy related to the impacts of recreation and development on these qualities. Contributing to the development of policies with regard to large-scale developments on the fringes of the National Park. Use as Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG), supporting emerging policies in the Local Development Plan which aim to protect the special qualities of the National Park. Forming baseline evidence in the development of a visitor management strategy, as referenced in the Environment Minister’s Strategic Grant Letter to the Welsh National Parks (29th March 2011). In addition it will inform community development, village plans, Glastir-targeted elements, countryside priorities, education and information through its contribution to understanding of sense of place. The methodology (comprising desk studies, fieldwork, consultation and writing-up) is in accordance with the current best practice guidelines for Landscape Character Assessment, and also utilises the Welsh LANDMAP landscape database. -

Channel View, the Marl, Cardiff Archaeological and Heritage Desk

Channel View, The Marl, Cardiff Archaeological and Heritage Desk-Based Assessment A115866-1 V2 Third Issue March 2021 Document prepared on behalf of Powell Dobson Architects tetratecheurope.com 1 Tetra Tech Southampton, The Pavilion, 1st Floor, Botleigh Grange Office Campus, Hedge End, Southampton, Hampshire, SO30 2AF Tetra Tech Limited Registered in England number: 1959704 Registered Office: 3 Sovereign Square, Sovereign Street, Leeds LS1 4ER VAT No: 431-0326-08 Document control Document: Archaeological and Heritage Desk Based Assessment Project: Channel View, Cardiff Client: Powell Dobson Architects Job Number: A115866-1 File Origin: A115866-1 Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment 31Mar21sh.docx Revision: V0 Date: September 2020 Prepared by: Checked by: Approved By: Samantha Hilton (PCIfA), Martin Brown, (MCIfA), Nigel Mann, Director Archaeological Consultant Associate Revision: Version 1 Date: March 2021 Prepared by: Checked by: Approved By: Samantha Hilton (PCIfA), Martin Brown, (MCIfA), Nigel Mann, Director Archaeological Consultant Associate Update to Section 10.2. tetratecheurope.com 2 Revision: Version 2 Date: March 2021 Prepared by: Checked by: Approved By: Samantha Hilton (PCIfA), Martin Brown, (MCIfA), Nigel Mann, Director Archaeological Consultant Associate Update to Section 10.2 and 11.1 tetratecheurope.com 3 CONTENTS 1. Non-Technical Summary ............................................................................................. 6 2. Introduction ...............................................................................................................