The Chronicle of Kamatari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan

The Numata Conference on Buddhist Studies: Violence, Nonviolence, and Japanese Religions: Past, Present, and Future. University of Hawaii, March 2014. Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan Mickey Adolphson University of Alberta 2014 What is religious violence and why is it relevant to us? This may seem like an odd question, for 20–21, surely we can easily identify it, especially considering the events of 9/11 and other instances of violence in the name of religion over the past decade or so? Of course, it is relevant not just permission March because of acts done in the name of religion but also because many observers find violence noa, involving religious followers or justified by religious ideologies especially disturbing. But such a ā author's M notion is based on an overall assumption that religions are, or should be, inherently peaceful and at the harmonious, and on the modern Western ideal of a separation of religion and politics. As one Future scholar opined, religious ideologies are particularly dangerous since they are “a powerful and Hawai‘i without resource to mobilize individuals and groups to do violence (whether physical or ideological of violence) against modern states and political ideologies.”1 But are such assumptions tenable? Is a quote Present, determination toward self-sacrifice, often exemplified by suicide bombers, a unique aspect of not violence motivated by religious doctrines? In order to understand the concept of “religious do Past, University violence,” we must ask ourselves what it is that sets it apart from other violence. In this essay, I the and at will discuss the notion of religious violence in the premodern Japanese setting by looking at a 2 paper Religions: number of incidents involving Buddhist temples. -

Print This Article

sJapanese Language and Literature JJournalapanese of the American Language Association and of Teachers Literature of Japanese Journal of the American Association of Teachers of Japanese jll.pitt.edu | Vol. 54 | Number 1 | April 2020 | DOI 10.5195/jll.2020.89 jll.pitt.edu | Vol. 54 | Number 1 | April 2020 | DOI 10.5195/jll.2020.89 ISSN 1536-7827 (print) 2326-4586 (online) ISSN 1536-7827 (print) 2326-4586 (online) Poetics of Acculturation: Early Pure Land Buddhism and the Topography of the Periphery in Orikuchi Shinobu’s The Book of the Dead Ikuho Amano Introduction Known as the exponent practitioner of kokubungaku (national literature), modernist ethnologist Orikuchi Shinobu (1887–1953) readily utilized archaic Japanese experiences as viable resources for his literary imagination. As the leading disciple of Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962), who is known as the founding father of modern folkloric ethnology in Japan, Orikuchi is often considered a nativist ethnologist whose works tend to be construed as a probing into the origin of the nation. He considered the essence of national literature as “the origins of art itself,” and such a critical vision arguably linked him to interwar fascism.1 Nevertheless, his nativist effort as a literatus was far from the nationalist ambition of claiming a socio-cultural unity. On the contrary, Orikuchi invested his erudition to disentangle the concatenation of the nation, religion, and people and thus presented ancient Japanese experience as discursive molecules rooted in each locality. In this regard, his novel Shisha no sho (The Book of the Dead, 1939) plays an instrumental role of insinuating the author’s nuanced modernist revisionism. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

Women and Japanese Buddhism

Barbara Ruch, ed.. Engendering Faith: Women and Buddhism in Premodern Japan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002. Illustrations, charts, maps. lxxviii + 706 pp. $69.00, cloth, ISBN 978-1-929280-15-5. Reviewed by Michiko Yusa Published on H-Buddhism (August, 2009) Commissioned by A. Charles Muller (University of Tokyo) This book marks a clear departure from the this process, and feminist scholarship, too, made male-oriented foci of traditional scholarship on its contribution. That the recent volume of the Ja‐ Japanese Buddhism and ventures to reconstruct panese Journal of Religious Studies ( JJRS, 2003, its history by incorporating women's voices.[1] All edited by Noriko Kawahashi and Masako Kuroki) of the essays address, from diverse angles, wom‐ is dedicated to "Feminism and Religion in Contem‐ en's roles in the history of Japanese Buddhism. porary Japan" speaks for the healthy unfolding of The volume begins with a foreword and preface, feminist studies in Japan, as this issue marks the followed by twenty-three weighty essays, inter‐ twentieth anniversary of the 1983 special issue of spersed with ninety-five illustrations, charts, and JJRS, "Women and Religion in Japan," the guest ed‐ maps, many of which are in full color; a list of itor of which was the late Kyōko Nakamura. characters; a selected bibliography; an index; and Indeed, Japanese society's acknowledgement information about the contributors. One of the of the importance of women's issues helped to distinctive features of this book is that it contains create the academic discipline of women's studies a substantial number of essays by a younger gen‐ as well as to promote the study of women in the eration of Japanese scholars, all translated into history of Japanese religions. -

Buddhist Sculpture and the State: the Great Temples of Nara Samuel Morse, Amherst College November 22, 2013

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Fall 2013 The Culture and Arts of Korea and Early Japan Sponsored by The Society for Asian Art Buddhist Sculpture and the State: The Great Temples of Nara Samuel Morse, Amherst College November 22, 2013 Brief Chronology 694 Founding of the Fujiwara Capital 708 Decision to move the capital again is made 710 Founding of the Heijō (Nara) Capital 714 Kōfukuji is founded 716 Gangōji (Hōkōji) is moved to Heijō 717 Daianji (Daikandaiji) is moved to Heijō 718 Yakushiji is moved to Heijō 741 Shōmu orders the establishment of a national system of monasteries and nunneries 743 Shōmu vows to make a giant gilt-bronze statue of the Cosmic Buddha 747 Casting of the Great Buddha is begun 752 Dedication of the Great Buddha 768 Establishment of Kasuga Shrine 784 Heijō is abandoned; Nagaoka Capital is founded 794 Heian (Kyoto) is founded Yakushiji First established at the Fujiwara Capital in 680 by Emperor Tenmu on the occasion of the illness of his consort, Unonosarara, who later took the throne as Empress Jitō. Moved to Heijō in 718. Important extant eighth century works of art include: Three-storied Pagoda Main Image, a bronze triad of the Healing Buddha, ca. 725 Kōfukuji Tutelary temple of the Fujiwara clan, founded in 714. One of the most influential monastic centers in Japan throughout the temple's history. Original location of the statues of Bonten and Taishaku ten in the collection of the Asian Art Museum. Important extant eighth century works include: Statues of the Ten Great Disciples of the Buddha Statues of the Eight Classes of Divine Protectors of the Buddhist Faith Tōdaiji Temple established by the sovereign, Emperor Shōmu, and his consort, Empress Kōmyō as the central institution of a countrywide system of monasteries and nunneries. -

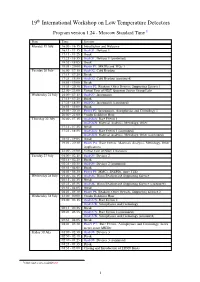

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - Moscow Standard Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 16:00 - 16:15 Introduction and Welcome 16:15 - 17:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O3: Instruments 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 20:00 - 21:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Tuesday 27 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 03:55 - 04:05 Break 04:05 - 05:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Wednesday 28 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting -

ACS42 01Kidder.Indd

The Vicissitudes of the Miroku Triad in the Lecture Hall of Yakushiji Temple J. Edward Kidder, Jr. The Lecture Hall (Ko¯do¯) of the Yakushiji in Nishinokyo¯, Nara prefecture, was closed to the public for centuries; in fact, for so long that its large bronze triad was almost forgotten and given little consideration in the overall development of the temple’s iconography. Many books on early Japanese Buddhist sculpture do not mention these three images, despite their size and importance.1) Yakushiji itself has given the impression that the triad was shielded from public view because it was ei- ther not in good enough shape for exhibition or that the building that housed it was in poor repair. But the Lecture Hall was finally opened to the public in 2003 and the triad became fully visible for scholarly attention, a situation made more intriguing by proclaiming the central image to be Maitreya (Miroku, the Buddha of the Fu- ture). The bodhisattvas are named Daimyo¯so¯ (on the Buddha’s right: Great wondrous aspect) and Ho¯onrin (left: Law garden forest). The triad is ranked as an Important Cultural Property (ICP), while its close cousin in the Golden Hall (K o n d o¯ ), the well known Yakushi triad (Bhais¸ajya-guru-vaidu¯rya-prabha) Buddha, Nikko¯ (Su¯ryaprabha, Sunlight) and Gakko¯ (Candraprabha, Moonlight) bodhisattvas, is given higher rank as a National Treasure (NT). In view of the ICP triad’s lack of exposure in recent centuries and what may be its prior mysterious perambulations, this study is an at- tempt to bring together theories on its history and provide an explanation for its connection with the Yakushiji. -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Chinese Religion and the Formation of Onmyōdō

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40/1: 19–43 © 2013 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture Masuo Shin’ichirō 増尾伸一郎 Chinese Religion and the Formation of Onmyōdō Onmyōdō is based on the ancient Chinese theories of yin and yang and the five phases. Practitioners of Onmyōdō utilizedYijing divination, magical puri- fications, and various kinds of rituals in order to deduce one’s fortune or to prevent unusual disasters. However, the term “Onmyōdō” cannot be found in China or Korea. Onmyōdō is a religion that came into existence only within Japan. As Onmyōdō was formed, it subsumed various elements of Chinese folk religion, Daoism, and Mikkyō, and its religious organization deepened. From the time of the establishment of the Onmyōdō as a government office under the ritsuryō codes through the eleventh century, magical rituals and purifications were performed extensively. This article takes this period as its focus, particularly emphasizing the connections between Onmyōdō and Chi- nese religion. keywords: Onmyōryō—ritsuryō system—Nihon shoki—astronomy—mikkyō— Onmyōdō rituals Masuo Shin’ichirō is a professor in the Faculty of Humanities at Tokyo Seitoku University. 19 he first reference to the Onmyōryō 陰陽寮 appears in the Nihon shoki 日本書紀. On the first day of the first month of 675 (Tenmu 4), various students of the Onmyōryō, the Daigakuryō 大学寮, and the Geyakuryō T外薬寮 (later renamed the Ten'yakuryō 典薬寮) are said to have paid tribute with medicine and rare treasures together with people from India, Bactria, Baekje, and Silla. On this day, the emperor took medicinal beverages such as toso 屠蘇 and byakusan 白散1 and prayed together with all his officials for longevity. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135 -

Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality Religion and Society

Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality Religion and Society Edited by Gustavo Benavides, Frank J. Korom, Karen Ruffle and Kocku von Stuckrad Volume 64 Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality New Approaches Edited by Birgit Kellner ISBN 978-3-11-041153-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041308-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041314-4 ISSN 1437-5370 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019941312 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Birgit Kellner, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston This book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Birgit Kellner 1 Introduction 1 Ingo Strauch 2 Buddhism in the West? Buddhist Indian Sailors on Socotra (Yemen) and the Role of Trade Contacts in the Spread of Buddhism 15 Anna Filigenzi 3 Non-Buddhist Customs of Buddhist People: Visual and Archaeological Evidence from North-West Pakistan 53 Toru Funayama 4 Translation, Transcription, and What Else? Some Basic Characteristics of Chinese Buddhist Translation as a Cultural Contact between India and China, with Special Reference to Sanskrit ārya and Chinese sheng 85 Lothar Ledderose 5 Stone Hymn – The Buddhist Colophon of 579 Engraved on Mount Tie, Shandong 101 Anna Andreeva 6 “To Overcome the Tyranny of Time”: Stars, Buddhas, and the Arts of Perfect Memory at Mt.