Provisioning Ecosystem Services Provided by the Hadejia Nguru Wetlands, Nigeria – Current Status and Future Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typha Grass Militating Against Agricultural Productivity Along Hadejia River, Jigawa State, Nigeria Sabo, B.B.1*, Karaye, A.K.2, Garba, A.3 and Ja'afar, U.4

Scholarly Journal of Agricultural Science Vol. 6(2), pp. 52-56 May, 2016 Available online at http:// www.scholarly-journals.com/SJAS ISSN 2276-7118 © 2016 Scholarly-Journals Full Length Research Paper Typha Grass Militating Against Agricultural Productivity along Hadejia River, Jigawa State, Nigeria Sabo, B.B.1*, Karaye, A.K.2, Garba, A.3 and Ja'afar, U.4 Jigawa Research Institute, PMB 5015, Kazaure, Jigawa State Accepted 21 May, 2016 This research work tries to examine the socioeconomic impact of typha grass in some parts of noth eastern Jigawa State, Nigeria. For better understanding of the field conditions with regards to the impact of the grass on the socioeconomy of the area (agriculture, fishing and the livelihood pattern), three hundred (300) questionnaires were designed and administered, out of which only two hundred and forty six (246) were returned. Findings from the questionnaire survey of some communities along river Hadejia show that, there is general reduction in the flow of water in the river channel over the last few years. This was attributed to blockages by typha grass and silt deposits within the river channel. There is also reduced or loss of cultivation of some crops particularly irrigated crops such as maize, rice, wheat and vegetables, fishing activities in the area is also affected by the grass. Moreover, communities have tried communal and individual manual clearance of the typha, while Jigawa State and Federal Governments are also carrying out mechanical clearance work in the channel. All these efforts have little impact. Key words: Typha grass, Irrigated crops, Hadejia River. -

Lake Chivero Holds About 250 000 Million Litres (264 000 Million Quarts) of Water and Is LAKE CHIVERO 2 Approximately 26 Km (10 Square Miles) Or ZIMBABWE 2 632 Ha

Lake Cahora Basa Lake Cahora Basa is a human made reser- voir in the middle of the Zambezi River in Mozambique, which is primarily used for the production of hydroelectricity. Cre- ated in 1974, this 12 m (39 ft) deep lake has been strategically built on a narrow gorge, enhancing the rapid collection of water and creating the pressure required to drive its giant turbines. The lake’s dam has a production capacity of 3 870 megawatts, making it the largest power-producing bar- rage on the African continent. After the construction of Cahora Basa Dam, its water level held constant for 19 • Large mammals, including the once- Cahora Basa Dam is used in Mozambique, years, resulting in a near-constant release abundant buffalo, have almost disap- with some sold to South Africa and Zim- of 847 m3 (1 108 cubic yards) over the same peared from the delta babwe. Lake Cahora Basa can actually be period. Observations before and 20 years • The abundance of waterfowl has de- seen as a ‘powerhouse’ of Southern Africa, after the dam’s impoundment, however, clined signifi cantly although damage to the generators dur- ing the civil war in 1972 has kept the plant reveal the following negative impacts, some • Floodplain ‘recession agriculture’ has from functioning at its originally antici- of which may also have been caused by declined signifi cantly pated levels. The construction of the dam other dams on the river (e.g. Kariba), as • Vast vegetated islands have appeared well as the effects of the country’s 20-year has been opposed by communities down in the river channel, many of which the Zambezi River, where it reduced the civil war —but nearly all of which have been have been inhabited by people directly infl uenced by the over-regulation annual fl ooding on which they rely for cul- of a major river system: • Dense reeds have lined the sides of tivation. -

The History and Future of Water Management of the Lake Chad Basin in Nigeria

143 THE HISTORY AND FUTURE OF WATER MANAGEMENT OF THE LAKE CHAD BASIN IN NIGERIA Roger BLEN" University of Cambridge Abstract The history of water management in Nigeriahas been essentially a history of large capital projects, which have ofkn been executed without comprehensive assessments of either the effects on downstream users or on the environment.In the case ofthe Chad basin, the principal river systems bringing waterto the lake are the Komadugu Yobeand Ngadda systems. The Komadugu Yobe, in particular, has ben impounded at various sites, notably Challawa Gorge and Tiga, and further dams are planned, notably at Kafin Zaki. These have redud the flow to insignificant levels near the lake itself. On the Ngadda system, the Alau dam, intended for urban water supply, has meant the collapse of swamp farming systems in the Jere Bowl area northmt of Maiduguri without bringing any corresponding benefits. A recent government-sponsored workshop in Jos, whose resolutions are appended to the paper, has begun to call into question existing waterdevelopment strategies andto call for a more integrated approach to environmental impact assessment. Keywords: water management, history, environment, Lake ChadBasin, Nigeria. N 145 Acronyms In a paper dealing with administrative history, acronyms are an unfortunate necessity if the text is not to be permanently larded with unwieldy titles of Ministries and Parastatals. The most important of those used in the text are below. ADP Agricultural Development Project CBDA Chad Basin Development Authority DID Department -

Impact of British Colonial Agricultural Policies on Jama'are Emirate, 1900

IMPACT OF BRITISH COLONIAL AGRICULTURAL POLICIES ON JAMA’ARE EMIRATE, 1900-1960 BY AMINA BELLO ZAILANI M.A/ARTS/03910/2008-2009 BEING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M.A.) DEGREE IN HISTORY, FACULTY OF ARTS MARCH, 2015 DECLARATION I, Amina Bello Zailani, hereby declare that this study is the product of my own research work and that it has never been submitted in any previous application for the award of higher degrees. All sources of information in this study have been duly and specifically acknowledged by means of reference. ____________________ ______________ Amina Bello Zailani Date ii CERTIFICATION This M.A Thesis titled ―IMPACT OF BRITISH COLONIAL AGRICULTURAL POLICIES ON JAMA’ARE EMIRATE, 1900-1960‖ by Amina Bello Zailani, has been certified to have met part of the requirements governing the award of Masters of Arts (M.A) in Department of History, Faculty of Arts, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and hereby approved. _________________________ _________________ Prof. Abdulkadir Adamu Date Chairman, Supervisory Committee _________________________ _______________ Dr. Hannatu Alahira, Date Member, Supervisory Committee ________________________ ________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Head of Department ________________________ ________________ Prof. A.Z. Hassan Date Dean, School of Postgraduate Studies iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the Glory of the Almighty Allah. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study would not have been possible without the Rahama i.e. mercy of Almighty Allah through the opportunity He afforded me to achieve this monumental feat. Scholarship or acquisition of knowledge is such a wonderful and complex phenomenon that one person cannot share in its glory. -

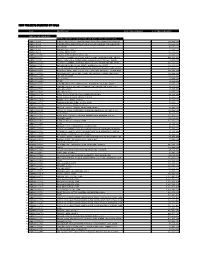

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Water Management Issues in the Hadejia-Jama'are-Komadugu-Yobe

Water Management Issues in the Hadejia-Jama'are-Komadugu-Yobe Basin: DFID-JWL and Stakeholders Experience in Information Sharing, Reaching Consensus and Physical Interventions Muhammad J. Chiroma. DFID-Joint Wetlands Livelihoods Project (JWL). Nigeria. [email protected]. Yahaya D. Kazaure. Hadejia-Jama'are River Basin Authority. Nigeria. [email protected]. Yahya B. Karaye. Kano State Water Board Nigeria. [email protected] and Abba J. Gashua. Yobe State ADP Nigeria. abba [email protected]. Abstract The Hadejia-Jama'are-Komadugu-Yobe Basin (HJKYB) is an inter-state and transboundary basin in Northern Nigeria. Covering an area of approximately 84,000 km 2 is an area of recent drama in water resources issues. Natural phenomena combining with long time institutional failure in management of water resources of the basin have led to environmental degradation, loss of livelihoods, resources use competition and conflicts, apathy and poverty among the various resource users in the basin. Unfortunately, complexities in statutory and traditional framework for water mf;magement has been a major bottleneck for proper water resources management in the basin. The Joint Wetlands Livelihoods (JWL) Project, which is supported by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID), has been designed to address increasing poverty and other resources use issues in the basin. Specifically, JWL is concerned with demonstrating processes that will help to improve the management of common pool resources (CPRs) - particularly water resources,.; in the Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands (HNWs) in particular and the HJKYB as a whole as a means ofreducing poverty. This process has brought together key stakeholders to form platforms for developing and implementing strategies to overcome CPR management problems. -

Review of Groundwater Potentials and Groundwater Hydrochemistry of Semi-Arid Hadejia-Yobe Basin, North-Eastern Nigeria

Journal of Geological Research | Volume 02 | Issue 02 | April 2020 Journal of Geological Research https://ojs.bilpublishing.com/index.php/jgr-a REVIEW Review of Groundwater Potentials and Groundwater Hydrochemistry of Semi-arid Hadejia-Yobe Basin, North-eastern Nigeria Saadu Umar Wali1* Ibrahim Mustapha Dankani2 Sheikh Danjuma Abubakar2 Murtala Abubakar Gada2 Abdulqadir Abubakar Usman1 Ibrahim Mohammad Shera1 Kabiru Jega Umar3 1. Department of Geography, Federal University Birnin kebbi, P.M.B 1157. Kebbi State, Nigeria 2. Department of Geography, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, P.M.B. 2346. Sokoto State, Nigeria 3. Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry, Federal University Birnin kebbi, P.M.B 1157. Kebbi State, Nigeria ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Understanding the hydrochemical and hydrogeological physiognomies of Received: 13 July 2020 subsurface water in a semi-arid region is important for the effective man- agement of water resources. This paper presents a thorough review of the Accepted: 24 July 2020 hydrogeology and hydrochemistry of the Hadejia-Yobe basin. The hydro- Published Online: 30 July 2020 chemical and hydrogeological configurations as reviewed indicated that the Chad Formation is the prolific aquifer in the basin. Boreholes piercing the Keywords: Gundumi formation have a depth ranging from 20-85 meters. The hydro- Hydrogeology chemical composition of groundwater revealed water of excellent quality, as all the studied parameters were found to have concentrations within Sedimentary aquifers WHO and Nigeria’s standard for drinking water quality. However, further Basement complex terrain studies are required for further evaluation of water quality index, heavy Physical parameters metal pollution index, and irrigation water quality. Also, geochemical, and stable isotope analysis is required for understanding the provenance of sa- Chemical parameters linity and hydrogeochemical controls on groundwater in the basin. -

1 Water Management Issues in the Hadejia-Jama'are

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Water Management Issues in the Hadejia-Jama’are-Komadugu-Yobe Basin: DFID-JWL and Stakeholders Experience in Information Sharing, Reaching Consensus and Physical Interventions Muhammad J. Chiroma, DFID-Joint Wetlands Livelihoods Project (JWL), Nigeria. [email protected]. Yahaya D. Kazaure, Hadejia-Jama’are River Basin Authority, Nigeria. [email protected]. Yahya B. Karaye, Kano State Water Board Nigeria. [email protected] Abba J. Gashua, Yobe State ADP Nigeria. [email protected] Abstract The Hadejia-Jama’are-Komadugu-Yobe Basin (HJKYB) is an inter-state and transboundary basin in Northern Nigeria. Covering an area of approximately 84,000 km2, it is an area of recent drama in water resource issues. Natural phenomena combined with long-term institutional failure in management of water resources of the basin have led to environmental degradation, loss of livelihoods, resource use competition and conflicts, apathy and poverty among the various resource users in the basin. The Joint Wetlands Livelihoods (JWL) Project, which is supported by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID), has been designed to address increasing poverty and other resource use issues in the basin. Specifically, JWL is concerned with demonstrating processes that will help to improve the management of common pool resources (CPRs) - particularly water resources - in the Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands (HNWs) in particular and the HJKYB as a whole as a means of reducing poverty. This process has brought together key stakeholders to form platforms for developing and implementing strategies to overcome CPR management problems. -

` Impact of Hadejia Valley Irrigation (Hvip) Project on Crop Productivity and Poverty Reduction in Jigawa State, Nigeria

` IMPACT OF HADEJIA VALLEY IRRIGATION (HVIP) PROJECT ON CROP PRODUCTIVITY AND POVERTY REDUCTION IN JIGAWA STATE, NIGERIA BY Mohammed Bashir UMAR (Ph. D. AGRIC/8714/2010-2011) DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND RURAL SOCIOLOGY FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA, KADUNA STATE NIGERIA MARCH, 2016 i IMPACT OF HADEJIA VALLEY IRRIGATION (HVIP) PROJECT ON CROP PRODUCTIVITY AND POVERTY REDUCTION IN JIGAWA STATE, NIGERIA BY Mohammed Bashir UMAR (PhD/ AGRIC / 8714 / 2010-11) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AND RURAL SOCIOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND RURAL SOCIOLOGY FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA, KADUNA STATE NIGERIA MARCH, 2016 ii DECLARATION I hereby declare that the work in this thesis entitled ‘’ Impact of Hadejia Valley Irrigation Project (HVIP) on Crop Productivity and Poverty Reduction in Jigawa State” has been written by me and it is my research work. No part of this work has been presented in any previous application for another Degree or Diploma in this or any other institution. All borrowed information has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided. Mohammed Bashir UMAR Date PhD/AGRIC/8714/2010-2011 iii CERTIFICATION This thesis entitled ―Impact of Hadejia Valley Irrigation Project (HVIP) on Crop Productivity and Poverty Reduction in Jigawa State” by Mohammed Bashir UMAR meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of PhD Agricultural Extension and Rural Sociology of the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. -

Hydro-Climatic Variability of the Hadejia-Jama'are River Systems In

Hydro-climatology: Variability and Change (Proceedings of symposium J-H02 held during 163 IUGG2011 in Melbourne, Australia, July 2011) (IAHS Publ. 344, 2011). Hydro-climatic variability of the Hadejia-Jama’are river systems in north-central Nigeria SHAKIRUDEEN ODUNUGA, IFEYINWA OKEKE, ADEMOLA OMOJOLA & LEKAN OYEBANDE Department of Geography, University of Lagos, Nigeria [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The study investigates the hydrological fluxes and land-use dynamics of the Hadejia-Jama’are basin in north-central Nigeria for sustainable agricultural development. The empirical Thornthwaite model was used to determine the potential evapotranspiration (PE) loss taking into account the land-use dynamics obtained from change detection using Landsat TM of 1986 and 2006. Using the results obtained from land- use dynamics, multiplying factors were determined and future water balances computed for high and medium emission climate change (HCC; MCC) scenarios for 50 and 100 years. The results reveal that the basin is currently recording a water deficit and that this will increase by 0.52% for the 50-year MCC, 0.53% for the 100-year MCC, 7.25% for the 50-year HCC and 37.82% for the 100-year HCC in Nguru, relative to the 2006 water balance. Sustainable agricultural practices and appropriate dam optimization techniques to ensure eco-friendly developments were recommended. Key words hydro-climatic; land use; water stress; climate change; Hadejia-Jama’are river systems, Nigeria INTRODUCTION The Hadejia-Jama’are River System (H-JRS) ecosystems and the human food production systems and livelihoods they support are threatened by the phenomenon of climate change, which over the years has resulted in a high level of variability and uncertainty in the annual flood regime (Yahya et al., 2010). -

Conservation and Sustainable Resource Use in the Hadejia–Jama

ORYX VOL 30 NO 2 APRIL 1996 Conservation and sustainable resource use in the Hadejia-Jama'are Valley, Nigeria William M. Adams and David H. L. Thomas Sustainable development is increasingly being seen as a legitimate, and locally critical, element in wildlife conservation. However, relatively few studies of projects attempt to combine conservation and development goals. The Hadejia-Nguru Wetland Conservation Project in Nigeria grew out of a concern for wildlife (particularly wetland birds), but has expanded to address issues of environmental sustainability and economic development at both the local and the regional scale. This paper assesses the achievements of the project's approach. Conservation and sustainable people are likely to oppose the establishment development of parks unless 'strenuous and imaginative ef- forts are made from the start to involve them Eltringham (1994) asked 'Can wildlife pay its in planning and development of the park', way?' and by posing that question he marked and to see that they benefit from any employ- a major shift in the way in which we under- ment generated (p. 725). The creation of new stand and conceive of conservation. During economic opportunities in a buffer zone the last decade, ideas about wildlife conser- around a national park may take human vation based on the designation of protected pressure off the national park itself. areas have increasingly given way to attempts Development here is being used as a means of to integrate human needs and conservation winning over local opposition to conservation objectives at the local scale and particularly to objectives, the carrot that balances the more a new focus on people and parks (McNeely conventional sticks, such as antipoaching and and Miller, 1984; Brandon and Wells, 1992; land-use control measures. -

Download Full Issue

ISSN (Print): ISSN (Online): ISSN (Print): 2616-051X | ISSN (electronic): 2616-0501 NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY (NIJEST) In Affiliation with The Nigerian Environmental Society (NES) https://www.nijest.com Volume 3 | Number 2 | October 2019 NIJEST / Nig. J. of Env. Sci. & Tech. 3 (2), October 2019 www.nijest.com NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY (NIJEST) https://www.nijest.com Volume 3 │ Number 2 │ October 2019 A PUBLICATION OF FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF BENIN IN AFFILIATION WITH THE NIGERIAN ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIETY Copyright © 2019 The Nigerian Journal of Environmental Sciences and Technology Published by: The Faculty of Environmental Sciences University of Benin P.M.B 1154, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria E: [email protected] In Partnership with Mindex Publishing Co. Ltd. 22, Benin Technical College Road, Ugbowo, P. O. Box 5089, Benin City, Nigeria Tel: +234802 345 3848, 803 740 4398, 805 475 5695 Email: [email protected], [email protected] website: www.mindexpublishing.com *Benin *Lagos *Abuja *Aba All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright Conventions. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher. Services For advertisements (online or in print copy of NIJEST), journal reprints and general enquiries please contact the secretariat or email the Editor – [email protected] Address for Correspondence The Nigerian Journal of Environmental Sciences and Technology (NIJEST) is Managed by: The Faculty of Environmental Sciences, University of Benin PMB 1154, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria E: [email protected] NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY (NIJEST) https://www.nijest.com EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Prof J.