Commerce and Exchange Buildings Listing Selection Guide Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽabbāsid Art: Squinch Fragmentation As The

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽAbbāsid Art: squinch fragmentation as The structural origin of the muqarnas La tradición sasánida en el arte ʿabbāssí: la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina como origen estructural de la decoración de muqarnas A tradição sassânida na arte abássida: a fragmentação do arco de canto como origem estrutural da decoração das Muqarnas Alicia CARRILLO1 Abstract: Islamic architecture presents a three-dimensional decoration system known as muqarnas. An original system created in the Near East between the second/eighth and the fourth/tenth centuries due to the fragmentation of the squinche, but it was in the fourth/eleventh century when it turned into a basic element, not only all along the Islamic territory but also in the Islamic vocabulary. However, the origin and shape of muqarnas has not been thoroughly considered by Historiography. This research tries to prove the importance of Sasanian Art in the aesthetics creation of muqarnas. Keywords: Islamic architecture – Tripartite squinches – Muqarnas –Sasanian – Middle Ages – ʽAbbāsid Caliphate. Resumen: La arquitectura islámica presenta un mecanismo de decoración tridimensional conocido como decoración de muqarnas. Un sistema novedoso creado en el Próximo Oriente entre los siglos II/VIII y IV/X a partir de la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina, y que en el siglo XI se extendió por toda la geografía del Islam para formar parte del vocabulario del arte islámico. A pesar de su importancia y amplio desarrollo, la historiografía no se ha detenido especialmente en el origen formal de la decoración de muqarnas y por ello, este estudio pone de manifiesto la influencia del arte sasánida en su concepción estética durante el Califato ʿabbāssí. -

I Mmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I

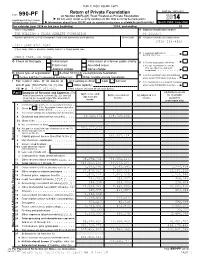

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¸ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2014 or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM & FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION 94-1655673 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (650) 234 -4500 2121 SAND HILL ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code m m m m m m m C If exemption application is I pending, check here MENLO PARK, CA 94025 G m m I Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm here m mand m attach m m m m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminatedm I Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I J X Fair market value of all assets at Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminationm I end of year (from Part II, col. -

17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/ Hungerford Footbridges

17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/ 149 Hungerford Footbridges 285 The Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges flank the Hungerford railway bridge, built in 1863. The footbridges were designed by the architects Lifschutz Davidson and were opened as a Millennium Project in 2003. 286 There are two Viewing Locations at Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges, 17A and 17B, referring to the upstream and downstream sides of the bridge. 150 London View Management Framework Viewing Location 17A Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream N.B for key to symbols refer to image 1 Panorama from Assessment Point 17A.1 Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream - close to the Lambeth bank Panorama from Assessment Point 17A.2 Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream - close to the Westminster bank 17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges 151 Description of the View 287 Two Assessment Points are located on the upstream side of Landmarks include: the bridge (17A.1 and 17A.2) representing the wide swathe Palace of Westminster (I) † of views available. A Protected Silhouette of the Palace of Towers of Westminster Abbey (I) Westminster is applied between Assessment Points 17A.1 The London Eye and 17A.2. Westminster Bridge (II*) Whitehall Court (II*) 288 The river dominates the foreground. In the middle ground the London Eye and Embankment trees form distinctive Also in the views: elements. The visible buildings on Victoria Embankment The Shell Centre comprise a broad curve of large, formal elements of County Hall (II*) consistent height and scale, mostly of Portland stone. St Thomas’s Hospital (Victorian They form a strong and harmonious building line. section) (II) St George’s Wharf, Vauxhall 289 The Palace of Westminster, part of the World Heritage Site, Millbank Tower (II) terminates the view, along with the listed Millbank Tower. -

March Newsletter

The Train at Pla,orm 1 The Friends of Honiton Staon Newsle9er 12 - March 2021 Welcome to the March newsle0er. As well as all the latest rail news, this month we have more contribuons from our members and supporters, as well as the usual update on engineering work taking place along our line over the next couple of months. We also take the opportunity to remember the 50th anniversary this year of the demolion of William Tite’s original staon building at Honiton. Hopefully, as the front image shows, Spring is on its way. Remember that you can read the newsle0er online or download a copy from our website. (Photograph by Vernon Whitlock) SWR Research Shows Likely Future Changes to Rail Travel Research commissioned by South Western Railway suggests that rail travel will look very different in a post-pandemic world. SWR has invesgated the possible impact of the pandemic on train travel and the main concerns passengers have about returning to the railways. They spoke to over 6,000 people across the region between April and October 2020. Their research has explored passenger’s atudes to SWR and to travel in general. These studies highlighted three key safety concerns held by passengers, that train companies need to connue to address. These are: other passengers’ adherence to safety measures, crowded trains, and the cleanliness of trains. The key finding of this research is that five key changes in behaviour are likely to have a long term impact on SWR. These are: • A move to remote meengs, held online through plaPorms such as Zoom and Microso Teams; • A move away from public transport back to the car; • More people choosing to work from home in the future; • A fla0ening of the rush hour peak, with a longer, but less intense peak period; • More people intending to take holidays in the UK in the future. -

Management, Leadership and Leisure 12 - 15 Your Future 16-17 Entry Requirements 18

PLANNING AND MANCHESTER MANAGEMENT, GEOGRAPHY ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHITECTURE INSTITUTE OF LEADERSHIP SCHOOL SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION AND LEISURE OF LAW SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT UNDERGRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 COURSES 2020 COURSES 2020 www.manchester.ac.uk/study-geography www.manchester.ac.uk/pem www.manchester.ac.uk/msa www.manchester.ac.uk/mie www.manchester.ac.uk/mll www.manchester.ac.uk www.manchester.ac.uk CHOOSE HY STUDY MANAGEMENT, MANCHESTER LEADERSHIPW AND LEISURE AT MANCHESTER? At Manchester, you’ll experience an education and environment that sets CONTENTS you on the right path to a professionally rewarding and personally fulfilling future. Choose Manchester and we’ll help you make your mark. Choose Manchester 2-3 Kai’s Manchester 4-5 Stellify 6-7 What the City has to offer 8-9 Applied Study Periods 10-11 Gain over 500 hours of industry experience through work-based placements Management, Leadership and Leisure 12 - 15 Your Future 16-17 Entry Requirements 18 Tailor your degree with options in sport, tourism and events management Broaden your horizons by gaining experience through UK-based or international work placements Develop skills valued within the global leisure industry, including learning a language via your free choice modules CHOOSE MANCHESTER 3 AFFLECK’S PALACE KAI’S Affleck’s is an iconic shopping emporium filled with unique independent traders selling everything from clothes, to records, to Pokémon cards! MANCHESTER It’s a truly fantastic environment with lots of interesting stuff, even to just window shop or get a coffee. -

The Custom House

THE CUSTOM HOUSE The London Custom House is a forgotten treasure, on a prime site on the Thames with glorious views of the river and Tower Bridge. The question now before the City Corporation is whether it should become a luxury hotel with limited public access or whether it should have a more public use, especially the magnificent 180 foot Long Room. The Custom House is zoned for office use and permission for a hotel requires a change of use which the City may be hesitant to give. Circumstances have changed since the Custom House was sold as part of a £370 million job lot of HMRC properties around the UK to an offshore company in Bermuda – a sale that caused considerable merriment among HM customs staff in view of the tax avoidance issues it raised. SAVE Britain’s Heritage has therefore worked with the architect John Burrell to show how this monumental public building, once thronged with people, can have a more public use again. SAVE invites public debate on the future of the Custom House. Re-connecting The City to the River Thames The Custom House is less than 200 metres from Leadenhall Market and the Lloyds Building and the Gherkin just beyond where high-rise buildings crowd out the sky. Who among the tens of thousands of City workers emerging from their offices in search of air and light make the short journey to the river? For decades it has been made virtually impossible by the traffic fumed canyon that is Lower Thames Street. Yet recently for several weeks we have seen a London free of traffic where people can move on foot or bike without being overwhelmed by noxious fumes. -

MANCHESTER HIGH QUALITY WORK SPACE in MANCHESTER MANCHESTER CITY CENTRE St Ann’S Square Is One of Manchester’S Most Well Known and Busiest Public Squares

MANCHESTER HIGH QUALITY WORK SPACE IN MANCHESTER MANCHESTER CITY CENTRE St Ann’s Square is one of Manchester’s most well known and busiest public squares. The original heart of the retail district, it now contains a cosmopolitan mix of business, retail, residential and leisure, all in a historic open space that is now the emotional centre of Manchester and a treasured Conservation Area. St Ann’s House is an imposing 20th century building sympathetic to its setting. The brick and Portland stone façade offers classic lines, topped off by a striking green pantile mansard roof. The modern canopy frames the designer shops at ground floor level, whilst large windows on the upper floors offer gorgeous views overlooking the Church and Square and flood the space with light. HOUSE ANN’S ANN’S ST ST ST PETER’S MANCHESTER EXCHANGE SHUDEHILL SQUARE CENTRAL VICTORIA THE SQUARE TRANSPORT NORTHERN KING MANCHESTER METROLINK PICCADILLY CONVENTION STATION NOMA PRINTWORKS METROLINK INTERCHANGE QUARTER STREET TOWN HALL STATION STATION COMPLEX MANCHESTER HOUSE SALFORD LOWRY HARVEY ARNDALE SPINNINGFIELDS RADISSON THE CENTRAL HOTEL NICHOLS CENTRE BLU MIDLAND ANN’S STATION SELFRIDGES EDWARDIAN HOTEL ST & CO HOTEL It’s all here at St Ann’s Square — street flower 8 MINS WALK 15 MINS WALK stalls, visiting markets, Manchester’s third oldest Church, the iconic Royal Exchange MANCHESTER MANCHESTER with its celebrated Theatre, fashionable arcades and the city’s top jewellers. Statues MANCHESTER VICTORIA PICCADILLY and fountains go hand in hand with high MANCHESTER AN fashion retail, boutique hotels, traditional ale M GE VICTORIA ILLE L R ST ST REE RE T houses and trendy restaurants. -

The Smithfield Gazette

THE SMITHFIELD GAZETTE EDITION 164 April 2018 REMEMBERING THE POULTRY MARKET FIRE Early on 23 January 1958 a fire broke out in the basement of the old Poultry Market building at Smithfield Market. It was to be one of the worst fires London had seen since the Blitz. The old Poultry Market was similar in style to the two remaining Victorian buildings – it was also designed by Sir Horace Jones and opened in 1875. In a moving ceremony held in Grand Avenue exactly sixty years after the fire started, the two firefighters who died were remembered by the unveiling of one of the Fire Brigades Union’s new red plaques. Wreaths were laid by Matt Wrack, General Secretary of the Fire Brigades Union, Greg Lawrence, Chairman of the Smithfield Market Tenants’ Association and Mark Sherlock, Superintendent of Smithfield Market. Serving and retired firefighters attended as well as Market tenants and representatives of the City of London. Two fire engines were also there. The fire burned for three days in the two and a half acre basement, which was full of crates of poultry as well as being lined with wooden match boarding which had become soaked with fat over a period of years – this meant that the fire spread exceptionally quickly. Reports of the time state that by dawn the stalls and market contents had been destroyed, the roof had collapsed and what was left was a blackened shell enclosing a twisted heap of ironwork and broken masonry. Flames 100 feet high lit the night sky. Firefighters from Clerkenwell fire station were the first to arrive on the scene, including Station Officer Jack Fourt-Wells, aged 46, and Firefighter Richard Stocking, 31, the two who lost their lives. -

1 Draft Paper Elisabete Mendes Silva Polytechnic Institute of Bragança

Draft paper Elisabete Mendes Silva Polytechnic Institute of Bragança-Portugal University of Lisbon Centre for English Studies, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Portugal [email protected] Power, cosmopolitanism and socio-spatial division in the commercial arena in Victorian and Edwardian London The developments of the English Revolution and of the British Empire expedited commerce and transformed the social and cultural status quo of Britain and the world. More specifically in London, the metropolis of the country, in the eighteenth century, there was already a sheer number of retail shops that would set forth an urban world of commerce and consumerism. Magnificent and wide-ranging shops served householders with commodities that mesmerized consumers, giving way to new traditions within the commercial and social fabric of London. Therefore, going shopping during the Victorian Age became mandatory in the middle and upper classes‟ social agendas. Harrods Department store opens in 1864, adding new elements to retailing by providing a sole space with a myriad of different commodities. In 1909, Gordon Selfridge opens Selfridges, transforming the concept of urban commerce by imposing a more cosmopolitan outlook in the commercial arena. Within this context, I intend to focus primarily on two of the largest department stores, Harrods and Selfridges, drawing attention to the way these two spaces were perceived when they first opened to the public and the effect they had in the city of London and in its people. I shall discuss how these department stores rendered space for social inclusion and exclusion, gender and race under the spell of the Victorian ethos, national conservatism and imperialism. -

2008 Romanesque in the Sousa Valley.Pdf

ROMANESQUE IN THE SOUSA VALLEY ATLANTIC OCEAN Porto Sousa Valley PORTUGAL Lisbon S PA I N AFRICA FRANCE I TA LY MEDITERRANEAN SEA Index 13 Prefaces 31 Abbreviations 33 Chapter I – The Romanesque Architecture and the Scenery 35 Romanesque Architecture 39 The Romanesque in Portugal 45 The Romanesque in the Sousa Valley 53 Dynamics of the Artistic Heritage in the Modern Period 62 Territory and Landscape in the Sousa Valley in the 19th and 20th centuries 69 Chapter II – The Monuments of the Route of the Romanesque of the Sousa Valley 71 Church of Saint Peter of Abragão 73 1. The church in the Middle Ages 77 2. The church in the Modern Period 77 2.1. Architecture and space distribution 79 2.2. Gilding and painting 81 3. Restoration and conservation 83 Chronology 85 Church of Saint Mary of Airães 87 1. The church in the Middle Ages 91 2. The church in the Modern Period 95 3. Conservation and requalification 95 Chronology 97 Castle Tower of Aguiar de Sousa 103 Chronology 105 Church of the Savior of Aveleda 107 1. The church in the Middle Ages 111 2. The church in the Modern Period 112 2.1. Renovation in the 17th-18th centuries 115 2.2. Ceiling painting and the iconographic program 119 3. Restoration and conservation 119 Chronology 121 Vilela Bridge and Espindo Bridge 127 Church of Saint Genes of Boelhe 129 1. The church in the Middle Ages 134 2. The church in the Modern Period 138 3. Restoration and conservation 139 Chronology 141 Church of the Savior of Cabeça Santa 143 1. -

Millbank Tower, London Sw1p 4Qp

MILLBANK TOWER, LONDON SW1P 4QP OFFICE TO RENT | 817 - 28,464 SQ FT | £30.00 PER SQ FT (INCL S/C) VICTORIA'S EXPERT PROPERTY ADVISORS TUCKERMAN TUCKERMAN.CO.UK 1 CASTLE LANE, VICTORIA, LONDON SW1E 6DR T (0) 20 7222 5511 MILLBANK TOWER, LONDON SW1P 4QP PLUG & PLAY OFFICES WITH STUNNING VIEWS DESCRIPTION AMENITIES Millbank Tower is located on the north side of the river Thames, with Air Conditioning Pimlico underground a short walk away, with St James’s Park and Raised Floor Westminster Underground Stations a 10 minute walk. Showers & Bike Racks Double Height Entrance Tenants not only benefit from the onsite amenities, but also on Horseferry Road, a two minute walk to the North and Victoria Street, a Manned Reception ten minute walk to the north. The available office floors are fitted to Fantastic Natural Light provide a mixture of open plan and cellular office space. AVAILABILITY TERMS FLOOR SIZE (SQ FT) AVAILABILITY RENT RATES S/C 30th 7,602 Available £30.00 Per Sq Ft (Incl Estimated at £20.00 Inclusive. Part 26th 3,678 27 April 2021 S/C) per sq ft. Part 25th 1,890 Available New lease(s) direct from the Landlord to September 2024. Part 17th 2,555 Available Part 14th 2,331 Available EPC Part 12th 2,665 Available Available upon request. Part 6th 817 Available LINKS Part 2nd 6,926 Available Website Virtual Tour TOTAL 28,464 GET IN TOUCH HARRIET DE FREITAS WILLIAM DICKSON Tuckerman Tuckerman 020 3328 5380 020 3328 5374 [email protected] [email protected] SUBJECT TO CONTRACT. -

Romanesque Architecture and Arts

INDEX 9 PREFACES 17 1ST CHAPTER 19 Romanesque architecture and arts 24 Romanesque style and territory: the Douro and Tâmega basins 31 Devotions 33 The manorial nobility of Tâmega and Douro 36 Romanesque legacies in Tâmega and Douro 36 Chronologies 40 Religious architecture 54 Funerary elements 56 Civil architecture 57 Territory and landscape in the Tâmega and Douro between the 19th and the 21st centuries 57 The administrative evolution of the territory 61 Contemporary interventions (19th-21st centuries) 69 2ND CHAPTER 71 Bridge of Fundo de Rua, Aboadela, Amarante 83 Memorial of Alpendorada, Alpendorada e Matos, Marco de Canaveses ROMANESQUE ARCHITECTURE AND ARTS omanesque architecture was developed between the late 10th century and the first two decades of the 11th century. During this period, there is a striking dynamism in the defi- Rnition of original plans, new building solutions and in the first architectural sculpture ex- periments, especially in the regions of Burgundy, Poitou, Auvergne (France) and Catalonia (Spain). However, it is between 1060 and 1080 that Romanesque architecture consolidates its main techni- cal and formal innovations. According to Barral i Altet, the plans of the Romanesque churches, despite their diversity, are well defined around 1100; simultaneously, sculpture invades the building, covering the capitals and decorating façades and cloisters. The Romanesque has been regarded as the first European style. While it is certain that Romanesque architecture and arts are a common phenomenon to the European kingdoms of that period, the truth is that one of its main stylistic characteristics is exactly its regional diversity. It is from this standpoint that we should understand Portuguese Romanesque architecture, which developed in Portugal from the late 11th century on- wards.