20050726-Stern.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism, Genocide, and Resistance: the Politics of Language And

114 PART TWO: Images as Sites of Struggles Nickel, H. M. 1991-1992. "Women in the German Democratic Republic and the New Federal States: Looking Backwards and Forwards." In German Politics and Society 24/25 (Winter): 34-52. Plenzdorf, U. 1980. Karla. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Racism, Genocide, and Resistance: Richter, R. 1981. "Herman Zschoche." In DEFA Spielfilmregisseure und ihre Kritiker [DEFA Feature Film Directors and Their Critics]. Vol. I, 224-241. Berlin: The Politics of Language Henschel. —. 1990. "Weder Wink& noch Zufall" [Neither Arbitrariness nor Chance]. In Film und Fernsehen 6: 41-44. and International Law Rosenberg, D. 1991. "The Colonization of East Germany." Monthly Review 4 (Sep- tember): 14-33. Schumann, M. 1992. Zweigeteilt. Uber den Umgang mit der SED-Vergangenheit [Di- JOY JAMES vided in Two. On the Treatment of the SED Past]. Hamburg: VSA Verlag. Ulbricht, W. 1966- "Brief des Genossen Walter Ulbricht an Genossen Prof. Dr. Kurt Maetzig" [Letter from Comrade Walter Ulbricht to Comrade Profes- sor Kurt Maetzig]. Neues Deutschland (23 January): 3. Wischnewski, K. 1975. "Ober Jakob und Andere" [On Jakob and Others]. Film und Fernsehen. (Reprinted in Behn, M. and Bock, H. 1988. Film und Gesellschaft in der DDR [Film and Society in the GDR], Vol. I. Hamburg.) GENOCIDE IN THE WAR ZONES Racism killed Malice Green, and if racism itself is not destroyed, it will destroy our nation. It got Malice Green at night. It will get you in the morning. -Rev. Adam' 1992 funeral eulogy for Malice Green, who was beaten to death by Detroit police Outside of a few communities, people rarely speak about racist state murders in a language that allows one to understand and mourn our losses. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 the FAN - Ed Bianchi

Domingo 9 17:00 THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD - Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 THE FAN - Ed Bianchi Lunes 10 CGAC 17:00 L’AVEU - Constantin Costa-Gavras 19:30 L’AMOUR À MORT - Alain Resnais 21:15 THE RAIN PEOPLE - Francis Ford Coppola Martes 11 17:00 A DANDY IN ASPIC - Anthony Mann, Laurence Harvey 19:00 THE DEADLY AFFAIR - Sidney Lumet 21:00 DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN - Wim Wenders Miércoles 12 16:30 SECHSE KOMMEN DURCH DIE WELT - Rainer Simon 18:00 TILL EULENSPIEGEL - Rainer Simon 19:45 JADUP UND BOEL - Rainer Simon 21:30 DIE FRAU UND DER FREMDE - Rainer Simon Jueves 13 17:45 WENGLER & SÖHNE, EINE LEGENDE - Rainer Simon 19:30 DER FALL Ö - Rainer Simon 21:15 WORK IN PROGRESS: CORTOMETRAJES DE MARCOS NINE - Marcos Nine Viernes 14 16:00 FÜNF PATRONENHÜLSEN - Frank Beyer 17:30 NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN - Frank Beyer 19:45 KARBID UND SAUERAMPFER - Frank Beyer 21:15 JAKOB, DER LÜGNER - Frank Beyer 23:00 DER VERDACHT - Frank Beyer Miércoles 19 21:30 DER TUNNEL - Roland Suso Richter Jueves 20 16:00 CARLOS - Olivier Assayas 21:45 DIE STILLE NACH DEM SCHUSS - Volker Schlöndorff Venres 21 16:00 8MM-KO ERREPIDEA - Tximino Kolektiv (Ander Parody, Pablo Maraví, Itxaso Koto, Mikel Armendáriz) 17:00 PROXECTO NIMBOS (SELECCIÓN DE CORTOMETRAJES) - Varios autores 17:45 WORK IN PROGRESS: O LUGAR DOS AVÓS - Víctor Hugo Seoane 20:15 EL CORRAL Y EL VIENTO - Miguel Hilari 21:15 OUROBOROS - Carlos Rivero, Alonso Valbuena Sábado 22 17:00 VIDEOCREACIÓNS - Olalla Castro 18:30 A HISTÓRIA DE UM ERRO - Joana Barros 20:15 TRUE ROMANCE. -

The Holocaust: Full Book List

Page 1 Holocaust Books for Young Readers Prejudice, Discrimination, Tolerance, Bullying, Being an Upstander The Sneetches by Dr. Seuss (1961) – Ages 4 - 8 Picture book that teaches children to be tolerant through a metaphor of what happened during the Holocaust https://greenvilleartspartnership.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/thesneetchesguide.p df https://www.teachingchildrenphilosophy.org/BookModule/TheSneetches Terrible Things: Allegory of the Holocaust by Eve Bunting (1996) Ages 6 and up. The author teaches children about the Holocaust through an allegory using animals. This introduction to the Holocaust encourages young children to stand up for what they think is right, without waiting for others to join them. It shows young readers the dangers of being silent in the face of danger. https://rapickering.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/terrible-things-questions.docx ______________________________________________________________ Brundibar by Toni Kushner (2003) – Ages 6 - 9 Picture book based on the Czech Opera performed by the children of Terezin. Brundibar tells the story of a brother and sister who stand up against tyranny with the help of other children in order to help their sick mother. http://www.ratiotheatre.org/Brund-SG www.pbs.org/now/arts/brundibar.html _____________________________________________________________ Star of Fear, Star of Hope by Jo Hoestlandt (1993) – Ages 7 - 10 The story of a nine year old girl who is confused by the disappearance of her Jewish friend during the Nazi occupation of Paris. www.holyfamilyregional.com/.../Star%20of%20Fear%20Star%20of%20Hope.p df _____________________________________________________________ Page 2 Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany by Ilse Koehn (1977) Ages 11 - 14 A memoir of Ilse Koehn who is classified a Mischling, second degree citizen in Nazi Germany. -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

Luis Trenker Der Schmale Grat Der Wahrheit

LUIS TRENKER DER SCHMALE GRAT DER WAHRHEIT CREDITS LUIS TRENKER D/AT|2015|BR|OV|90´ Regie: Wolfgang Murnberger Drehbuch: Peter Probst Kamera: Peter von Haller Produktion: Annie Brunner, Andreas Richter Darsteller: Tobias Moretti, Brigitte Hobmeier, Anatole Taubman WOLFGANG MURNBERGER FILMOGRAPHIE 2015 Das ewige Leben 2011 Mein bester Feind 2009 Der Knochenmann 2004 Silentium 2000 Komm, süsser Tod 1990 Himmel oder Hölle VORSTELLUNGEN STARNBERG SCHLOSSBERGHALLE 02.08., 19:30 UHR SCHLOSS SEEFELD 03.08., 17:00 UHR DIESSEN 04.08., 20:00 UHR WWW.FSFF.DE MR. TURNER - MEISTER DES LICHTS WILLIAM TURNER MR. TURNER CREDITS GB | 2014 | DCP | DE | 150´ Regie: Mike Leigh Drehbuch: Mike Leigh Kamera: Dick Pope Produktion: Georgina Lowe Darsteller: Dorothy Atkinson, Paul Jesson, Timothy Spall MIKE LEIGH FILMOGRAPHIE 2010 Another Year 2008 Happy-Go-Lucky 2004 Vera Drake 2002 All or Nothing 1997 Karriere Girls 1996 Lügen und Geheimnisse 1993 Nackt VORSTELLUNGEN SEEFELD 01.08., 11:00 UHR STARNBERG 02.08., 10:30 UHR HERRSCHING 09.08., 11:00 UHR FÜNF SEEN FILM FESTIVAL 2015 WALK THE LINE JOHNNY CASH CREDITS WALK THE LINE USA | 2005 | BR | DE | 136´ Regie: James Mangold Drehbuch: James Mangold, Gill Dennis Kamera: Phedon Papamichael Produktion: Cathy Konrad, James Keach Darsteller: Joaquin Phoenix, Reese Witherspoon, Robert Pa- trick, Ginnifer Goodwin, Dallas Roberts, Dan John Miller JAMES MANGOLD FILMOGRAPHIE 2013 Wolverine: Weg des Kriegers 2007 Todeszug nach Yuma 2005 Walk the Line 2003 Identität - Identity 2001 Kate & Leopold 1999 Durchgeknallt VORSTELLUNGEN STARNBERG 02.08., 22:00 UHR 21:30 UHR OPEN AIR BIERGARTEN HOCHSTADT 05.08., 21:30 UHR WWW.FSFF.DE FÜNF SEEN FILM FESTIVAL 2015 WWW.FSFF.DE MICHAEL VERHOEVEN FILMOGRAPHIE (Auswahl) 1967 Paarungen (auch Drehbuch) 1969 Der Kommissar - Dr. -

Ernst Thälmann – Führer Seiner Klasse (1955) Propaganda Für Arbeiterklasse, Partei Und Heroismus

Ernst thälmann – FührEr sEinEr KlassE (1955) Propaganda für Arbeiterklasse, Partei und Heroismus 1 FilmographischE angabEn 3 2 Filminhalt 3 3 HistorischE KontExtualisiErung 4 4 DiDaKtischE übErlEgungEn 7 5 ArbEitsanrEgungEn 11 6 MatErial 13 7 LitEratur 29 2 Unterrichtsmaterial Ernst Thälmann – Führer seiner Klasse www.ddr-im-film.de 1 FilmographischE angabEn Regie Kurt Maetzig Drehbuch Willi Bredel, Michael Tschesno-Hell, Kurt Maetzig Kamera Karl Plintzner, Horst E. Brandt schnitt Lena Neumann Musik Wilhelm Neef bauten Otto Erdmann, Willy Schiller, Alfred Hirschmeier Kostüme Gerhard Kaddatz produktion DEFA-Studio für Spielfilme (Potsdam-Babelsberg) uraufführung 07.10.1955, Ost-Berlin/Volksbühne Länge 140 Minuten FSK ab 12 Auszeichnungen Karlovy-Vary-Filmfestival 1956: Preis für den besten Schauspieler an Günther Simon Darstellerinnen | Darsteller Günther Simon (Ernst Thälmann), Hans-Peter Minetti (Fiete Jan- sen), Karla Runkehl (Änne Hansen), Paul R. Henker (Robert Dirhagen), Hans Wehrl (Wilhelm Pieck), Karl Brenk (Walter Ulbricht), Michel Piccoli (Maurice Rouger) Gerd Wehr (Wilhelm Flo- rin), Walter Martin (Hermann Matern), Georges Stanescu (Georgi Dimitroff), Carla Hoffmann (Rosa Thälmann), Erich Franz (Arthur Vierbreiter), Raimund Schelcher (Krischan Daik), Fritz Diez (Hitler), Hans Stuhrmann (Goebbels) 2 Filminhalt Der Film behandelt das Leben des Vorsitzenden der Kommunistischen Partei Deutsch- lands, Ernst Thälmann, in den Jahren von 1930 bis zu seinem Tode 1944. In lose aneinander gereihten Szenen werden vor allem die politische Arbeit des Parteiführers gezeigt. Thälmann wohnt zu Beginn der 1930er-Jahre in einem Zimmer einer typischen Berliner Mietskasernen- wohnung, das ihm von seinem Parteifreund Fiete Jansen und dessen schwangerer Frau Änne untervermietet wird. Fiete hat jahrelang im Gefängnis gesessen. Änne ist als Mitglied des kommunistischen Jugendverbandes für die KPD politisch aktiv. -

The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 12-15-2020 The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Gideon Reuveni University of Sussex Diana University Franklin University of Sussex Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reuveni, Gideon, and Diana Franklin, The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism. (2021). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Edited by IDEON EUVENI AND G R DIANA FRANKLIN PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS | WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-711-9 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of librar- ies working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61249-703-7. Cover artwork: Painting by Arnold Daghani from What a Nice World, vol. 1, 185. The work is held in the University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep, Arnold Daghani Collection, SxMs113/2/90. -

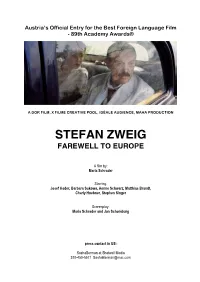

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

German Videos - (Last Update December 5, 2019) Use the Find Function to Search This List

German Videos - (last update December 5, 2019) Use the Find function to search this list Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness.LLC Library CALL NO. GR 009 Aimée and Jaguar DVD CALL NO. GR 132 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder. with Brigitte Mira, El Edi Ben Salem. 1974, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A widowed German cleaning lady in her 60s, over the objections of her friends and family, marries an Arab mechanic half her age in this engrossing drama. LLC Library CALL NO. GR 077 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD CALL NO. GR 134 A/B Alles Gute (chapters 1 – 4) CALL NO. GR 034-1 Alles Gute (chapters 13 – 16) CALL NO. GR 034-4 Alles Gute (chapters 17 – 20) CALL NO. GR 034-5 Alles Gute (chapters 21 – 24) CALL NO. GR 034-6 Alles Gute (chapters 25 – 26) CALL NO. GR 034-7 Alles Gute (chapters 9 – 12) CALL NO. GR 034-3 Alpen – see Berlin see Berlin Deutsche Welle – Schauplatz Deutschland, 10-08-91. [ Opening missing ], German with English subtitles. LLC Library Alpine Austria – The Power of Tradition LLC Library CALL NO. GR 044 Amerikaner, Ein – see Was heißt heir Deutsch? LLC Library Annette von Droste-Hülshoff CALL NO. GR 120 Art of the Middle Ages 1992 Studio Quart, about 30 minutes. -

Das Kind Im Koffer

Szene aus MDR-Produktion „Nackt unter Wölfen“ Buchenwald-Überlebende Apitz, Stefan Jerzy Zweig 1964, Szene aus DDR-Film „Nackt unter Wölfen“ 1962: Tapfere Antifaschisten besiegen Nazi-Schergen Das Kind im Koffer Fernsehen Mit einer Neuverfilmung des DDR-Bestsellers „Nackt unter Wölfen“ erinnert die ARD an die Befreiung des Konzentrationslagers Buchenwald vor 70 Jahren. Die Geschichte wird ideologisch entrümpelt, aber die ganze Wahrheit wird noch immer nicht erzählt. Von Martin Doerry m 11. April 1945 überfliegen ame - Unter den Gefangenen aus den Reihen Mann, der sich ihnen in den Weg stellt. rikanische Artillerie-Aufklärer das des kommunistischen Untergrunds gibt es Schließlich kommen aus der Lautsprecher - AKonzentrationslager Buchenwald, nun kein Halten mehr. Hunderte stürmen anlage des KZs die erlösenden Worte eines in der Ferne sind Panzermotoren zu hö - aus ihren Baracken auf das Tor und die Häftlings: „Wir sind frei!“ Jubel bricht aus, ren. Unter den SS-Leuten bricht Panik Wachtürme des KZs zu. Mit Gewehren glücklich fallen sich die ausgemergelten aus. Einige flüchten, andere wollen noch und Handgranaten, die sie für diesen Tag Gestalten in die Arme. schnell sämtliche Häftlinge des Lagers versteckt haben, überwältigen die Kämp - Mit diesen triumphierenden Bildern erschießen. fer ihre Bewacher, sie töten jeden SS- endet einer der bekanntesten DDR-Filme, 136 DER SPIEGEL 79 / 867: Kultur „Nackt unter Wölfen“, 1962 von Frank hener Wissenschaftler wie Julius H. Schoeps die die moralische Integrität seiner Mithäft - Beyer gedreht, nach der Vorlage des gleich - oder David A. Hackett geholt. linge beweisen sollte: Ein Transport aus namigen Buchs von Bruno Apitz, des mit In Buchenwald waren zwischen 1937 Auschwitz bringt im Frühjahr 1945 einen etwa zwei Millionen verkauften Exempla - und 1945 etwa 250 000 Menschen inhaftiert, dreijährigen jüdischen Jungen nach Bu - ren populärsten Romans der DDR.