Study of Representation in Aeschylus' the Persians and Ferdowsi's Eskandar in Shahnameh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Some Account of the Arabic Work Entitled " Nihd- Yatu'l-Irab Fi Akhbdri'l-Furs Iva'l-'Arab," Particularly of That Part Which Treats of the Persian Kings

195 ART. X.—Some Account of the Arabic Work entitled " Nihd- yatu'l-irab fi akhbdri'l-Furs iva'l-'Arab," particularly of that part which treats of the Persian Kings. By EDWARD Gr. BROWNE, M.A., M.R.A.S. To the curious book of which the full title stands at the head of this article, I have already alluded in my communi- cation to the Journal of January, 1899, on The Sources of Dawlatshdh, pp. 51-53. I now propose to give such account of its contents as is possible within the limits here prescribed. For this purpose I have made use of the Cambridge Codex (belonging to the Burckhardt Collection) marked QQ. 225. Though the book is a rare one, at least three other manuscripts are known — two in the British Museum (see the old Arabic Catalogue, pp. 418 and 581)l and one (marked A. 1741) at Gotha. The last was used by Professor Noldeke, in his reference to the Nihayat, at pp. 475-476 of his excellent Geschichte . der Sasaniden. He describes it as "in the main a quite arbitrary recension of Dinawari, though here [namely, in the Romance of Bahrain Chubin] it had before it an essentially fuller text than this," and briefly characterizes it as " das seltsame, ziemlich schwindelhafte Werk." When I first lighted on the book at Cambridge, not being aware of the existence of other copies, or of Noldeke's unfavourable judgment as to its value, I was elated beyond measure, believing that I had at last found the substance of that 1 These MSS., marked Add. -

The Persian Achaemenid Architecture Art Its Impact ... and Influence (558-330BC)

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 The Persian Achaemenid Architecture Art its Impact ... and Influence (558-330BC) Assistant professor Dr. Iman Lafta Hussein a a Department of History, College of Education, Al Qadisiya University, Ministry of Higher Education and Research, Republic of Iraq Abstract The Achaemenid Persians founded an empire that lasted for two centuries (550-331 BC) within that empire that included the regions of the Near East, Asia Minor, part of the Greek world, and highly educated people and people such as Babylon, Assyria, Egypt, and Asia Minor. Bilad Al-Sham, centers of civilization with a long tradition in urbanism and civilization, benefited the Achaemenids in building their empire and the formation of their civilization and the upbringing of their culture. It also secured under the banner of late in the field of civilization, those ancient cultures and mixed and resulted in the Achaemenid civilization, which is a summarization of civilizations of the ancient East and reconcile them, and architecture and art were part of those civilizational mixing, It was influenced by ancient Iraqi and Egyptian architecture as well as Greek art. In addition, it also affected the architecture of the neighboring peoples, and its effects on the architecture of India and Greece, as well as southern Siberia, but the external influences on the architecture of Achaemenid. It does not erase the importance of the special element and the ability to create a special architecture of Achaemenid civilization that has the character and characteristics and distinguish it from its counterparts in the ancient East. -

Ocjene I Prikazi

OCJENE I PRIKAZI Dr F1ehiim Baj.raktareVJić, Osnovi prakse tUrSkog jeZJilka :za pr,o~teklih se turske gramatike. Lzdanje Naučne lmji dam ·decenija. ge. Beog:rad 1962. · Na ·n.ašiJ. žalost, to je Učinio dr Fe h:iin Bajra:kitarevrić. Njegovo wda:nje Jeh1iitschlkLnog udžbenika,. čak ako je Dužnost nam je da zabiliiežimo po priiPremlJeno na brzu ruku, :za mteme javu OVJog. upibeniika ikojli j.e objavljen pokeoo njegove katedre, jednom alb pod Jmenom dra F·ehima. Baj~rakttan:e javljeno, teško da !Pfredstavlja pođistrek V1ića, . dugogodiš:nj,eg, rediOVIUOJg profesora i ohraihrenje za ooe kQj'i počinju da ·lUČe ·i š,efa lkat·edre za 1011Lj·entalistilku Filo turslk:i jooilk, a na velikoj ddsrtanci m loškog falkulteta u Beogradu. ostaje za IIJ.IivoOIIIl turkologije đ. osmani Dr Fehim Bajnakta~rević u p.redgo stike u našoj zemljii. varu prezentli.ra ovaj udžbenik Ikao sa Za pisca ovih ~edova, ikojli je pa mostalan ~ad, namijenjen za IPQ'1;lre!be žl}i:vo sraV'!liio »Os.nove tui'!s.ke grama nasta.ve 'turskog jellilka na našim uni tike« sa Tiirikische Konversatil()l!ls vemiltetima. Grammatdik, biLa bi naučma dumoSit da Međutim, _'-potrebno je unijeti. korek ul!aZii u a:naldzu prerade koju je dr turu u ovakav stav dra Fehima Bajrak..: Fehdm Bajlt'aktarević ±zv·ršOO. AH, ono tarevrića. Ovaj udžbenliik nilje samosita što se mora reći je to da ova prerada lan :raQ. ma Feh:ima Bajrakta.revića, ukazuje da dr Fehi1m Bajralttarević, nego 01!1 tPredstavlja. Skraćeno i mjesiti maka[- se lkooistio Denyem, Rossddem i miČIIl:o, ru IP'Jtgledu pojedinih li:zriaza d c'lrugi:ma, ostavlja av]m posLom utisaik t~ina, retušilrano !izldanje Tilrkische da prenebregava rezultate moderne Konversations-Grammatik ~d ·H. -

A Study of the Illustrations of the Sharaf-Nama in the Chester Beatty Library's Anthology. Pers 124 of 1435-36

PERSICA XVI, 2000 67 A STUDY OF THE ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SHARAF-NAMA IN THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY’S ANTHOLOGY. PERS 124 OF 1435-36 Caroline Singer University of Edinburgh The purpose of this article is to discuss a portion of the 121 illustrations of the Chester Beatty Library’s Anthology Pers 124.1 It will concentrate primarily on the illus- trations to Nizami’s Sharaf-Nama, the first part of his epic poem, the Iskandar-Nama, extolling the life of Alexander the Great. In addition, it will consider the overall choice of subjects illustrating the Iskandar-nama made by Persian manuscript painters from c. 1380-1474. It will also address the problem of provenance inherent in this understudied manuscript. The Anthology has variously been attributed to provincial Southern Iranian schools, and, most recently, has been connected with a group of near-contemporary man- uscripts thought to have been executed in Sultanate India. In conclusion, a comparison will be made with a Shah-Nama of similar date, and with remarkably similar stylistic traits, in the hope that further work may be done on the basis of this preliminary study. The manuscript, now in two leather-bound volumes, comprises an anthology of Per- sian and Arabic literature, richly illustrated with 121 miniatures within the pages of the text. Originally, two double frontispieces adorned the beginning of Volume One; the right half of the first frontispiece is now missing, and the left page is damaged, obliterat- ing the name of the patron and place of manufacture. It is, however, still possible to appreciate the lavish and fairly sophisticated illumination of these frontispieces, deco- rated in blue, black and predominantly gold, with medallions encircling a central rosette and angelic figures in all four corners. -

Pismo III 2005

Pismo, III/1 Izlazak ovog broja Pisma finansijski su potpomogli: • Udruženje građana KULT, Sarajevo • gospođa Ljubinka Petrović-Ziemer • gospodin Emir Granov • gospođa Dorothea König 1 Sadržaj UDK 81+82 ISSN 1512-9357 PISMO Journal for Linguistics and Literary Studies Zeitschrift für Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft III/1 Published by Herausgegeben von: BOSNIAN PHILOLOGICAL SOCIETY BOSNISCHE PHILOLOGISCHE GESELLSCHAFT SARAJEVO, 2005 2 Pismo, III/1 UDK 81+82 ISSN 1512-9357 PISMO Časopis za jezik i književnost GODIŠTE 3, BROJ 1 SARAJEVO, 2005. 3 Sadržaj Izdavač: Bosansko filološko društvo, B. Nušića 15d, Sarajevo Savjet: prof. dr. Esad Duraković (Sarajevo), prof. dr. Dževad Karahasan (Graz – Sarajevo), prof. dr. Svein Mønnesland (Oslo), prof. dr. Angela Richter (Halle), prof. dr. Norbert Richard Wolf (Würzburg) Redakcija: Adnan Kadrić, Sanjin O. Kodrić, Munir Mujić, Merima Osmankadić, Ismail Palić, Vahidin Preljević, Vedad Smailagić i Amela Šehović Glavni urednik: Ismail Palić Časopis izlazi jedanput godišnje. 4 Pismo, III/1 Sadržaj I. RASPRAVE I ČLANCI JEZIK Amra Mulović: Diglosija u savremenom arapskom jeziku ............................................. 11 Munir Drkić: Arapski utjecaj na nastanak novoperzijskoga jezika (7–11. st.) ............ 25 Alen Kalajdžija: Usmeno jezičko stvaralaštvo Umihane Čuvidine .................................. 40 Ivo Pranjković: Što je kao ............................................................................................... 55 Đenita Haverić: ba] u perzijskom jeziku i njegovi prijevodni] ﺑﺎ -

1720-Eski Chaghlar Ve Turk Tarixinin Ilk Donemleri-Ismet Parmaqsizoghlu

ismet PARMAKSIZOĞLU Yaşar ÇAĞLAYAN GENEL TARİH I Eski Çağlar ve Türk Tarihinin İlk Dönemleri Ankara, 1976 FUNDA YAYINLARI, Sanlı Han 105/311 Kızılay/ANKARA Birinci Basım Kapak : Sadri Pekak Dizgi, Basl<ı, Kapak Baskısı, C iit: TİSA l\/latbaaoılık Ltd. Şti. Mitinatpaşd Cad. 62 İÇİNDEKİLER Sayfa No. ÖNSÖZ XI ESKİÇAĞ TARİHİ BİRİNCİ BÖLÜM : G İ R İ Ş 1. Eskiçağ Tarihine Başlarken .............................................. 3 1.1. Eskiçağ Tarihinin Sınırları ...................................... 3 1.2. Tarihöncesi .................................................................... 5 1.2.1. Tarihöncesi Kültür Anlaşmaları ..................... 7 1.2.2. Ön Asya Uygarlık Alanlarının Tarihöncesi ... 10 1.3. Yazı 17 2. Çin ......................................................................................... 19 2.1. Çin Tarihinin Özellikleri ve Önemi .......................... 20 2.2. Çinin Siyasal Tarihi ...................................................... 21 2.3. Çin Düşüncesinin Temelleri ................. ..................... 27 2.4. Çinin Türk Tarihince Değeri ...................................... 30 3. Hint ................................................ ,....................................... 31 3.1. Hint Tarihinin Özellikleri ........................................... 31 3.2. Siyasal Tarih .................................................................. 34 3.3. Hint Düşüncesi .............................................................. 36 İKİNCİ BÖLÜM : ESKİ DOĞU UYGARLIKLARI ................. 43 1. Mezopotamya Tarihi -

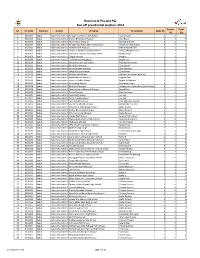

Final List of Pcs and Pss Run-Off Presidential Election, 2014

Final List of PCs and PSs Run-off presidential election, 2014 Female Total No PC Code Province District PC Name PC locatioin Male PS PS PSs 1 0101001 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan High School Asakzai lane 3 3 6 2 0101002 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mullah Mahmood Mosque Shur Bazar 3 3 6 3 0101003 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Akhir-e-Jada Mosque Maiwand Street 2 2 4 4 0101004 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan Secondary School Se Dokan Chandawaul 3 3 6 5 0101005 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Pakhtaferoshi Mosque Pakhta forushi lane 2 3 5 6 0101006 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Daqeqi-e-Balkhi Secondary School Saraji, Ahangari Lane 3 3 6 7 0101007 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mastoora-e-Ghoori Seconday School Babay Khudi 3 3 6 8 0101008 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Eidgah Mosque Abdgah 3 3 6 9 0101009 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Fatiha-Khana-e-Baghqazi Baghe Qazi 2 2 4 10 0101010 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Aisha-e-Durani High School Pule baghe Umumi 3 2 5 11 0101011 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Bibi Sidiqa Mosque Chendawul 2 1 3 12 0101012 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Sar-e-Gardana Mosque Sare Gardana 1 1 2 13 0101013 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Takya-Khana-e-Omomi Chendawul 3 2 5 14 0101014 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Khawja Safa Mosqe Asheqan wa Arefan Bala Joy 1 1 2 15 0101015 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Baghbankocha Mosque Baghbanlane 2 1 3 16 0101016 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Onsuri-e-Balkhi School Baghe Ali Mardan 3 2 5 17 0101017 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Imam Baqir Mosqe Hazaraha village 2 1 3 18 0101018 Kabul -

M'sian Origins010508(210817)

MALAYSIAN ORIGINS® by E.S.Shankar 1/75 a brief history of the peoples of Malaysia® CONTENTS PG. f o r e w o r d 2 m e l a k a – the beginning 6 malay roots 10 sejarah melayu – malay annals 12 chinese armada 17 of birds’ nest s and dragons in the east 20 golden age of melaka 23 dev illed curry chicken 25 islam the pilla r 27 fleeting dutchman - double dutch and bugi s 29 the legend of hang tuah 31 homo sapien 34 race for the future 40 sejarah melayu revisited – t h e a l exander and persian problem 44 aryavartha – t h e n o r t h 49 daksh i n a p a t h a – t h e s o u t h 54 r a j a marong mahawangsa or kedah annals 59 the golden chersonese 62 the truth shall remain the truth 64 A p p e n d i x : melaka sultanate 68 sejarah melayu parameswara ancestry 69 alexander ancestry 70 persian ances t r y 71 c o r r e s p ondence with a ghani ismail 73- 75 MALAYSIAN ORIGINS® by E.S.Shankar 2/75 a brief history of the peoples of Malaysia® F o r e w o r d We have been led to believe by revisionist historians t h a t for all intents and purposes, M’sian history commences w i t h t h e conversion to Islam and t h e installation of I s k a n d a r Shah (Parameswara) as Sultan of Melaka i n 1 4 0 0 AD. -

Rome and Parthia: Power Politics and Diplomacy Across Cultural Frontiers1

Culture Mandala, Volume 13, special issue 3, June 2019 © R. James Ferguson Rome and Parthia: Power Politics and Diplomacy Across Cultural Frontiers1 by Dr R. James Ferguson Parthians and Persians: The Horizon of Hellenistic and Roman Power Modern international relations, though still focused in part on issues of power and power balance, has in recent years been forced to assess a wide range of religious, economic and cultural factors that cross boundaries and form deep linkages among social systems that are transnational in nature.2 This problem is prominent where national or imperial frontiers expand across areas still linked by trade, religious affiliation, and migration flows, and where the patterns of diplomacy and war themselves form transboundary linkages. Such frontiers were enduring problems that focused the attentions of major civilisations for centuries, e.g. China with its complex frontier-relations to the west and north-west (followed by a sense of vulnerably to European naval power from the south-east, at first via the South China Sea), Russia’s historical obsession with an expanding eastern frontier, and European concern about the power, influence and later instability of the Ottoman Empire. This problem was also found in the Graeco-Roman world, whose interaction with Persia formed one of the great ‘east-west’ dichotomies in European thought. If not exactly 'transnational', since modern nation-states had not yet been formed, such 'trans-imperial' patterns complicated the creation of stable borders, undermined power-balancing, and reduced the mutual acceptance of zones for cultural and religious interaction. Indeed, it seems likely that 'notions of state, territory and boundary' had developed to a substantial degree in Imperial Rome and Sasanid Persia, shaping complex regional interactions during both war and peace.3 Persia and Parthia were two of the great 'others' that shaped the limits of the Graeco- Roman world,4 and were also imagined worlds where European values were explored, excluded, and projected. -

Drugs Politics

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 213.205.194.120, on 21 Jun 2019 at 10:36:11, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/E2EFB2A2A59AC5C2D6854BC4C4501558 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 213.205.194.120, on 21 Jun 2019 at 10:36:11, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/E2EFB2A2A59AC5C2D6854BC4C4501558 Drugs Politics Iran has one of the world’s highest rates of drug addiction, estimated to be between two and seven per cent of the entire population. This makes the questions this book asks all the more salient: what is the place of illegal substances in the politics of modern Iran? How have drugs affected the formation of the Iranian state and its power dynamics? And how have governmental attempts at controlling and regulating illicit drugs affected drug consumption and addiction? By answering these questions, Maziyar Ghiabi suggests that the Islamic Republic’s image as an inherently conservative state is not only misplaced and inaccurate, but in part a myth. In order to dispel this myth, he skilfully combines ethnographic narratives from drug users, vivid field observations from ‘under the bridge’, with archival material from the pre- and post-revolutionary era, statistics on drug arrests and interviews with public officials. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/ 9781108567084. MAZIYAR GHIABI is an Italian/Iranian social scientist, ethnographer and historian, currently a lecturer at the University of Oxford and Titular Lecturer at Wadham College. -

THE EVOLUTION of TRADITIONAL THEATRE and the DEVELOPMENT of MODERN THEATRE in IRAN by Iraj Emami Thesis Submitted to the Faculty

THE EVOLUTION OF TRADITIONAL THEATRE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN THEATRE IN IRAN by Iraj Emami Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts, for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh September 1987 To Husayn Ali Zadeh, Muhammad Reza Lutfi and Muhammad Reza Shajarian. ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to describe and analyse the evolution of traditional theatre in Iran and its development towards occidental and modern theatre, up to the Revolution of 1979. The introductory chapter consists of a brief historical background to the Persian theatre and a discussion of its roots. Chapter II examines the origin of popular theatrical forms in Iran and its development from such popular narrative forms such as story-telling, poetic recitation, oratorical contest, public amusements and puppet theatre. Chapter III concerns Taziya, the passion play of Iran, the most famous and influential form of theatre in the nineteenth century. Taziya's origin, form, music and all related forms of traditional drama have been examined in this chapter. Chapter IV focuses on the evolution of Taqlid and its developed form, Takht-i-Hawzi, the popular Iranian comedy. Chapter V looks at the development of theatre in Iran during the Qajar era when both comic and tragic theatre, or Takht-i Hawzi and Taziya grew in two opposite directions and the first direct steps towards the evolution of a written text for the performance of occidental theatre were taken. Chapter VI ;s a survey of the formation of modern theatre in Iran and the role of education in its development. Also the impact of western culture on this evolution is examined.