St Augustine's Use of the Psalms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AD TE LEVAVI • “Hosanna” Literally Means, “Help” Or “Save, I Pray.” It Is Most Prominent in the Hallel: Psalms 113-118

Covenant was brought forward was pulled by “two cows which had never been yoked.” (see John 19:41) 8 Most of the crowd spread their cloaks on the road, and others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road. • The crowds laid their cloaks on the road just as it was done at the inauguration of Jehu (2 Kings 9:12-13). • Branches and palms were used for religious processions (see 1 Maccabees 13:51; 2 Maccabees 10:6-7). THE FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT 9 And the crowds that went before him and that followed him were shouting, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!” AD TE LEVAVI • “Hosanna” literally means, “help” or “save, I pray.” It is most prominent in the Hallel: Psalms 113-118. The Hallel was a collection of Psalms for morning prayer. The crowds sang out Psalm 118:25-26, specifically. This To You I Lift Up part of the Hallel was sung during the feasts of the Passover and of the tabernacles, Israel’s great Jubilee, when the people walked around Study Notes for the Christian Layperson the altar with the branches of the palm and trees (Leviticus 23:40). by: Rev. Roberto E. Rojas, Jr. These were also the words of the Great Hosanna, the song of praise used in the time of the second temple when the people passed around the altar of the sacrifice, during the feast of the tabernacles. Collect of the Day: Stir up Your power, O Lord, and come, that by Your protection we may be • “Name of the Lord” — See the 2nd Commandment, the 1st Petition of rescued from the threatening perils of our sins and saved by Your mighty the Lord’s Prayer, the Sanctus (LSB 195), and the hymn “O Lord, How deliverance; for You live and reign with the Father and the Holy Spirit, one Shall I Meet You” (LSB 334). -

Tender Mercies in English Scriptural Idiom and in Nephi's Record

Tender Mercies in English Scriptural Idiom and in Nephi’s Record Miranda Wilcox Nephi records divine beings inviting humans to participate in the sacred story of salvation and humans petitioning divine beings for aid in their mortal affliction. The first chapter of Nephi’s story introduces linguistic, textual, and narrative questions about how humans should engage with and produce holy books that memorialize these divine- human relations in heaven and on earth. For Nephi, a central element of these relationships is “tender mercies” (1 Nephi 1:20). What are tender mercies? How do the Lord’s tender mercies make the chosen faithful “mighty, even unto the power of deliverance”? Nephi’s striking phrase has become popular in Latter-day Saint discourse since Elder David A. Bednar preached of the “tender mercies of the Lord” at general conference in April 2005. He defined tender mercies as “very personal and individualized blessings, strength, pro- tection, assurances, guidance, loving-kindnesses, consolation, support, and spiritual gifts which we receive from and because of and through the Lord Jesus Christ.”1 I would like to extend this discussion and reconsider this definition with respect to Nephi’s record by explor- ing the biblical sources and the transmission of this beloved phrase through English scriptural idiom. 1. David A. Bednar, “The Tender Mercies of the Lord,”Ensign , May 2005, 99. 75 76 Miranda Wilcox Nephi explains that he has acquired “a great knowledge of the good- ness and the mysteries of God” and that he will share this knowledge in his record (1 Nephi 1:1). -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Psalm-25-Digging-Deeper.Pdf

Chico Alliance Church Message February 1, 2015 Digging Deeper on the Message Pastor David Welch “Lord, Do Remember Me” Psalm 25 - The Psalms can be approached in so many different ways. This particular Psalm divides nicely under the R.A.P categories. Resolve, Affirmation and Petition appear all through the song. Not accounting for the Hebrew poetry factor, which often repeats similar thoughts in differing words, I identified 16 resolves, 13 affirmations and 18 petitions scattered throughout this Psalm. These categories can be found in many of the Psalms. Most of the time they appear randomly throughout the Psalm. Try identifying the categories in another Psalm. I gathered all the verses of Psalm 25 under these three categories. RESOLVE -- David’s desire to trust God alone Since David began with resolve, I want to explore his resolves first and then the affirmations of truth that stimulated the resolves and inspired the petitions. David expressed his personal action throughout the song. To You, O LORD, I lift up my soul. O my God, in YOU I trust… Psalm 25:1-2 Lift up is another way of saying, Lord I appeal to you or give my attention to you. I trust in You. You are the object of my trust. I wait for YOU. Psalm 25:21 For YOU I wait all the day. Psalm 25:5 The term “wait” goes deeper than waiting around wishing something will happen. It indicates a certain expectation that God will act in His way and His time and I continue on in the present anticipating God’s appearance in the future. -

Psalm 84-88 Monday 27Th July - Psalm 84

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 84-88 Monday 27th July - Psalm 84 How lovely is your dwelling place, 7 They go from strength to strength, Lord Almighty! till each appears before God in Zion. 2 My soul yearns, even faints, 8 Hear my prayer, Lord God Almighty; for the courts of the Lord; listen to me, God of Jacob. my heart and my flesh cry out 9 Look on our shield, O God; for the living God. look with favour on your anointed one. 3 Even the sparrow has found a home, 10 Better is one day in your courts and the swallow a nest for herself, than a thousand elsewhere; where she may have her young— I would rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my a place near your altar, God Lord Almighty, my King and my God. than dwell in the tents of the wicked. 4 Blessed are those who dwell in your house; 11 For the Lord God is a sun and shield; they are ever praising you. the Lord bestows favour and honour; 5 Blessed are those whose strength is in you, no good thing does he withhold whose hearts are set on pilgrimage. from those whose walk is blameless. 6 As they pass through the Valley of Baka, 12 Lord Almighty, they make it a place of springs; blessed is the one who trusts in you. the autumn rains also cover it with pools. One of my boys loves to have his back scratched and preferably scratched hard. As I was scratching his back one night, he said: “This is the life!” At that moment, his idea of the good life was pretty simple. -

HOPE in the WORD Is a Plan for You to Connect with God by Being in YOUR Bible for 90 Days

HOPE IN THE WORD is a plan for you to connect with God by being in YOUR bible for 90 days. The format will be Facebook Live from Monday to Thursday @ 10am and will allow you the flexibility to listen in/read at your own pace. In this custom plan, we will read ~ 33% of the Bible, from Old Testament accounts to all the Psalms, Proverbs, the gospel of Mark, and several of the New Testament epistles including Romans, Philippians, and others. Join us for 90 days of being fed with the Word of God! DAY DATE READING DONE 1 Jan 4, 2021 Mark 1-3; Proverbs 1 2 Jan 5, 2021 Mark 4-5; Psalm 1-2 3 Jan 6, 2021 Mark 6-7; Psalm 3-4; Romans 1 4 Jan 7, 2021 Mark 8-9; Psalm 4-5 5 Jan 11, 2021 Mark 10-12; Romans 2 6 Jan 12, 2021 Mark 13-14; Proverbs 2 7 Jan 13, 2021 Mark 15-16; Psalm 6-7; Romans 3 8 Jan 14, 2021 Genesis 1-2; Psalm 8-9 9 Jan 18, 2021 Genesis 3-4; Romans 4 10 Jan 19, 2021 Genesis 6-8; Psalm 10-11 11 Jan 20, 2021 Genesis 7-9; Psalm 12 12 Jan 21, 2021 Genesis 11-12; Romans 5 13 Jan 25, 2021 Genesis 13-14; Psalm 13-15 14 Jan 26, 2021 Genesis 15-17; Romans 6 15 Jan 27, 2021 Genesis 18-19; Psalm 16-17 16 Jan 28, 2021 Genesis 20-21; Romans 7 17 Feb 1, 2021 Genesis 22; Psalm 18-19; Proverbs 3-4 18 Feb 2, 2021 Genesis 23-24; Psalm 20 19 Feb 3, 2021 Genesis 25-26; Proverbs 5; Romans 8 20 Feb 4, 2021 Genesis 27-28; Psalm 21-22 21 Feb 8, 2021 Genesis 29-30; Psalm 23-25 22 Feb 9 2021 Genesis 31-32; Proverbs 6 23 Feb 10, 2021 Genesis 33-34; Romans 9-10 24 Feb 11, 2021 Genesis 35,37; Romans 11 25 Feb 15, 2021 Genesis 38-39; Psalm 26-28 26 Feb 16, 2021 Genesis -

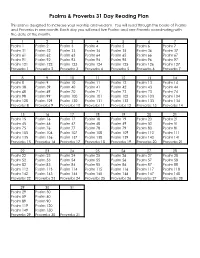

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

To You I Lift up Study Notes for the Christian Layperson By: Rev

THE FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT AD TE LEVAVI To You I Lift Up Study Notes for the Christian Layperson by: Rev. Roberto E. Rojas, Jr. Matthew 21:1-9 ESV Collect of the Day: Author and Date: Stir up Your power, O Lord, and come, Matthew Levi the apostle around AD 50. This is the Triumphal Entry of Jesus that by Your protection we may be rescued from Bethany to Jerusalem (Matthew 21:1-9; Mark 11:1-11; Luke 19:28-44; from the threatening perils of our sins John 12:12-19). and saved by Your mighty deliverance; for 1 Now when they drew near to Jerusalem and came to Bethphage, to the Mount You live and reign with the Father and the of Olives, then Jesus sent two disciples, Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen. • This text is recorded by all four Evangelists and is read twice in the course of a year: Advent 1 and Palm Sunday. Note also that the text for Trinity 10 takes Introit: place immediately after this. Psalm 25:4-5, 21-22 (antiphon: Psalm 25:1-3a) • Bethphage was a village on the Mount of Olives around 1 mile from the — To You, O Lord, I lift up my soul. temple in Jerusalem. The Mount of Olives was named in the prophecy Psalm: of the Lord’s advent (Zechariah 14:4). 24 (antiphon: v. 7) — The King of Glory • The two disciples are unidentified (see Mark 6:7; Luke 10:1). Old Testament Reading: • This all took place on the first day of the week, Sunday, on the 10th Jeremiah 23:5-8 — The Righteous Branch of Nisan (see John 12:1, 12). -

Metrical Psalter Book 1 V 1-0-3

The Psalms in metre Book 1 Psalms 1-41 Book 1 ; Page 1 © Dru Brooke-Taylor 2015, the author’s moral rights have been asserted. For further information both on copyright and how to use this material see https://psalmsandpsimilar.wordpress.com v 1.0.3 : 15 vi 2015 Book 1 ; Page 2 Table of Contents Psalm 1 (SHa) CM 5 Psalm 2 (SHa)CM 6 Psalm 3 (SHa) CM 8 Psalm 4 (SHa)CM 10 Psalm 5 (TBa) CM 11 Psalm 6 (TBa) CM 13 Psalm 7 (SHa) CM 14 Psalm 8 (SHa) CM 16 Psalm 8-B (DBT) 13,13,13,13,13,13 18 Psalm 9 (SHa) CM 20 Psalm 10 (SHa) CM 22 Psalm 11 (DBT) CM 24 Psalm 12 - (SHa) CM 25 Psalm 13 (SHa) CM 26 Psalm 14 - (SHa) CM 27 Psalm 14-B - Another version (TB unaltered) LM 28 Psalm 15 - (SHa) CM 30 Psalm 16 - (SHa) CM 31 Psalm 17 - (SHa) CM 33 Part 2 34 Psalm 18 - (SHa) CM 35 Psalm 19 (SHa) CM 40 Psalm 20 (SHa) CM 42 Psalm 21 (SHa) DCM 43 Psalm 22 (SHa) CM 45 Part 2 46 Part 3 46 Psalm 23 (R) CM 48 Psalm 23 - B (SHa) CM 48 Psalm 23 - C A version by Sir H. W. Baker 8787 49 Psalm 23 - D - a version by Addison 88 88 88 50 Psalm 24 (TBa) DCM 52 Psalm 24 - B Dr Watts version to Kingsbridge in LM 54 Part 2 55 Psalm 25 (SHa) DSM 56 Part 2 57 Psalm 26 (SHa) CM 59 Psalm 27 (SHa) CM 60 Psalm 28 (SHa) CM 62 Psalm 29 (SHa) CM 63 Psalm 30 (DBT) DCM 65 Psalm 31 (SHa) CM 67 Psalm 32 (SHa) CM 70 Psalm 33 (TB) CM 72 Part 2 73 Psalm 34 (TB) CM 74 Part 2 75 Psalm 35 (TBa) CM 76 Book 1 ; Page 3 Part 2 77 Part 3 77 Psalm 36 (SHa) CM 79 Psalm 37 (TBa) 888 888 81 Part 2 82 Part 3 83 Part 3 84 Psalm 38 (SHa) CM 86 Part 2 87 Psalm 39 (SHa) CM 88 Psalm 40 (SHa) CM 90 Psalm 40 - B (TBa) LM 92 Psalm 41 (SHa) DCM 94 Book 1 ; Page 4 Psalm 1 (SHa) CM Playford has a good tune in three line harmony, which floats between Emi and G Maj, which is below as ‘Old First’ with the addition of an alto line and some ornamentation. -

Reflections on the Saddest Psalm in the Psalter

Verbum et Ecclesia ISSN: (Online) 2074-7705, (Print) 1609-9982 Page 1 of 7 Original Research ‘Darkness is my closest friend’ (Ps 88:18b): Reflections on the saddest psalm in the Psalter Author: On the face of it, there are no bright spots in Psalm 88 – no hope at all for the bitterly lamenting 1 Ernst R. Wendland psalmist, or seemingly for his readers today either. This intensely individual complaint Affiliation: expresses ‘the dark night of the soul … a state of intense spiritual anguish in which the 1Department of Ancient struggling, despairing believer feels he is abandoned by God’ (Boice 1996:715–716). So why Studies, Stellenbosch has this disorienting ‘psalm of disorientation’ (Brueggemann & Bellinger 2014:7) been University, South Africa included in the Psalter, the penultimate prayer of Book III, and what are we to make of it? Corresponding author: One cannot of course provide definitive answers, but several suggestions may be offered Ernst Wendland, based on the opinions of a number of capable Psalms scholars, coupled with some personal [email protected] observations. After citing the text in Hebrew, along with my own English translation, the Dates: poetic structure of the psalm is overviewed and then selected features of its artistry and Received: 29 Oct. 2015 rhetoric are discussed. This study concludes with an assortment of reflections that speak to Accepted: 09 Feb. 2016 the theological importance of this dark psalm and its relevance for all those in particular who Published: 25 May 2016 wake up in the morning, consider their current situation in life, and wonder: ‘Can it get any How to cite this article: worse?’ Wendland, E.R., 2016, ‘“Darkness is my closest Intradisciplinary and/or interdisciplinary implications: This study illustrates how a close friend” (Ps 88:18b): literary–structural analysis can serve to reveal insights of exegetical and theological significance Reflections on the saddest while at the same time critiquing certain received scholarly positions. -

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) Calvin, Jean (1509-1564) (Alternative) (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Calvin found Psalms to be one of the richest books in the Bible. As he writes in the introduction, "there is no other book in which we are more perfectly taught the right manner of praising God, or in which we are more powerfully stirred up to the performance of this religious exercise." This comment- ary--the last Calvin wrote--clearly expressed Calvin©s deep love for this book. Calvin©s Commentary on Psalms is thus one of his best commentaries, and one can greatly profit from reading even a portion of it. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer This volume contains Calvin©s commentary on chapters 67 through 92. Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Commentary on Psalms 67-92 1 Psalm 67 2 Psalm 67:1-7 3 Psalm 68 5 Psalm 68:1-6 6 Psalm 68:7-10 11 Psalm 68:11-14 14 Psalm 68:15-17 19 Psalm 68:18-24 23 Psalm 68:25-27 29 Psalm 68:28-30 33 Psalm 68:31-35 37 Psalm 69 40 Psalm 69:1-5 41 Psalm 69:6-9 46 Psalm 69:10-13 50 Psalm 69:14-18 54 Psalm 69:19-21 56 Psalm 69:22-29 59 Psalm 69:30-33 66 Psalm 69:34-36 68 Psalm 70 70 Psalm 70:1-5 71 Psalm 71 72 Psalm 71:1-4 73 Psalm 71:5-8 75 ii Psalm 71:9-13 78 Psalm 71:14-16 80 Psalm 71:17-19 84 Psalm 71:20-24 86 Psalm 72 88 Psalm 72:1-6 90 Psalm 72:7-11 96 Psalm 72:12-15 99 Psalm 72:16-20 101 Psalm 73 105 Psalm 73:1-3 106 Psalm 73:4-9 111 Psalm 73:10-14 117 Psalm 73:15-17 122 Psalm 73:18-20 126 Psalm 73:21-24 -

2 Samuel & 1 Chronicles with Associated Psalms

2 Samuel& 1 Chronicles w/Associated Psalms (Part 2 ) -Psalm 22 : The Psalm on the Cross . This anguished prayer of David was on the lips of Jesus at his crucifixion. Jesus’ prayed the psalms on the cross! Also, this is the most quoted psalm in the New Testament. Read this and then pray this the next time you experience anguish. -Psalm 23 : The Shepherd Psalm . Probably the best known psalm among Christians today. -Psalm 24 : The Christmas Processional Psalm . The Christmas Hymn, “Lift Up Your Heads, Yet Might Gates” is based on this psalm; also the 2000 chorus by Charlie Hall, “Give Us Clean Hands.” -Psalm 47 : God the Great King . Several hymns & choruses are based on this short psalmcelebrating God as the Great King over all. Think of “Psalms” as “Worship Hymns/Songs.” -Psalm 68 : Jesus Because of Hesed . Thematically similar to Psalms 24, 47, 132 on the triumphant rule of Israel’s God, with 9 stanzas as a processional liturgy/song: vv.1-3 (procession begins), 4-6 (benevolent God), 7-10 (God in the wilderness [bemidbar]), 11-14 (God in the Canaan conquest), 15-18 (the Lord ascends to Mt. Zion), 19-23 (God’s future victories), 24-27 (procession enters the sanctuary), 28-31 (God subdues enemies), 32-35 (concluding doxology) -Psalm 89 : Davidic Covenant (Part One) . Psalms 89 & 132 along with 2 Samuel 7 & 1 Chronicles 17 focus on God’s covenant with David. This psalm mourns a downfall in the kingdom, but clings to the covenant promises.This psalm also concludes “book 4” of the psalter.