Why We Do What We Do: Georgians Speak About Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM 42Nd STFM Annual Spring Conference C O N F E R E N C E April 29-May 3, 2009 Hyatt Regency Denver HIGHLIGHTS Denver, CO

42ND STFM ANNUAL SPRING CONFERENCE The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine April 29-May 3, 2009 Hyatt Regency Denver FINAL PROGRAM 42nd STFM Annual Spring Conference C O N F E R E N C E April 29-May 3, 2009 Hyatt Regency Denver HIGHLIGHTS Denver, CO Transforming Education to Meet the STFM’s Annual Showcase—providing the best oppor- Needs of the Personal Medical Home tunity for camaraderie with colleagues in family medicine 3 Transmitting the STFM Core Purpose to through education, meetings, informal gatherings, and Learners Across the Continuum social events. 3 Identifying and Teaching the Knowledge, Patient-centered Medical Home—We are offering a Skills, and Attitudes Learners Need Within number of sessions related to the PCMH. Look for the ses- the Personal Medical Home sion track MH, which highlights them. 3 Developing and Implementing New Curricula for the Personal Medical Home: Expanded Poster Session—This year’s conference will Lessons Learned continue to provide two scholastic poster sessions—as well as research, special P4 poster displays and osteopathic 3 Evaluating Competence in Providing the resident posters too! Personal Medical Home: Best Practices Networking—Participants continue to rank networking as the most important factor for their attendance at the con- ference. Make connections and contacts with your peers through common interest and special topic breakfasts, the poster sessions, exhibit hall and group meetings, and optional community service project. TABLE OF CONTENTS STFM Village— STFM will feature our programs, prod- ucts, and learning opportunities in the STFM Village. The President’s Message ...................................... 1 STFM Village will include incentives for members to pay it Overall Conference Schedule ......................2-6 forward by donating in various ways: to the STFM Foun- Preconference Workshops ............................ -

Miscellaneous Surveys

_,. -- -~--1 -_-~~<:::_~,:.:·-f.:J_"'~--:\.:~~-~~:~::..:~!..1--· ----- -- ··- -- --- ..) _:,, _·) ,,.,~ a2.ter info:rrr,ation o·btained from CIP, Curre<"lt fatalog, etc.? j....-fl,G. I '-1. -:_,_·.s yo;r entire collection cataloge~ (except for _jo\lrnals)'?_, 'f<'ha.t is.~o>? -) ;jC--' -l.r0o--:. )~o~~- ~, ~ t.t.-v...J:..t.' <f'tQJ<-~- ~~- t •1Ld~lM7 c:· /' wrt3.t type of catalog do you have (dictionary, e-cc. ) ? fuc_, fi OY')Q$ j 6. How do you obtain catalog cards? .)L fU- Cl4 VV~.tNY'-U'~~ '7 l. How are cards prepared (typed, one typed and others xeroxed, etc.)? 8. flow much of b'.ldget spent on cataloging activities (including your or assj stant s' time.- specify %of person's time),. , if possible? 9. How many books are cataloged per year? (DO 10.- Are the majority of books purchased at one time or at regular intervals (quarterly, etc.) ? ~ t;J.. a~ K.u4i!... 1 ' _..~ ... How __ much original cataloging do you do? 16 ~~ 1t ~ ci:J~&J-- Ho~ many books do you have in your collection? 4i 00 0 P~_ease include a typical card and bring this questionnaire to the nerl meetinr: or rrail to M. Gibbs. Please :Lnclude any other pertinent remarks on back. 51 19'7'"( \... - roes:I:BL!t ~~ FOO CON$Pft'I'ItJM MON'"l'riLY MZETINGS I, ' ' . f:·,' Please rate tiM following topi<:!s in order of your interest. (ex. n•. ::of:.t interested • Hl) If you have no interest in having such e. r)rogre.m at. a ~eting, l.esYi! box blank. -

Connected Members (Query-Based Exchange) As of 9/1/19

Connected Members (Query-Based Exchange) As of 9/1/19 State Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Development Disabilities Agencies (DBHDD) – Shares patient discharge records Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) – Views patient health information for youth in their care Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH) – Bi-directional submission gateway for immunization data (GRITS), eLab and Syndromic Surveillance reporting; contributes immunization information Georgia Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) – Views patient health information for youth in their care Georgia Medicaid/Department of Community Health (DCH) – Contributes Medicaid claims (health, dental, pharmacy) information. Medicaid providers using GAMMIS can view patient health information. Care Care Management Organizations facilitate care coordination for Medicare and Medicaid patients, Management including PeachCare for Kids(r), Georgia Families(r) and Planning for Healthy Babies (r) (P4HB(r)) Organizations Amerigroup – shares care plans and views patient health information CareSource – shares care plans and views patient health information Peach State – views patient health information WellCare – views patient health information Health Shares patient health information from their connected providers Systems Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA) – Georgia’s largest children’s hospital Emory Healthcare – Georgia’s largest academic hospital Grady Health System – Georgia’s largest public hospital Gwinnett Health System – Serves one of the -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

March 6, 2019 – March 12, 2019 Need Projection Analyses

Use the links below for easy navigation Letters of Intent Letters of Intent - Expired New CON Applications Pending/Complete Applications Pending Review/Incomplete CON Applications Office of Health Planning Recently Approved CON Applications Recently Denied CON Applications Appealed CON Projects Letters of Determination Requests for Miscellaneous Letters of Determination Appealed Determinations DET Review LNR Conversion Requests for LNR for Diagnostic or Therapeutic Equipment Requests for LNR for Establishment CERTIFICATE OF NEED of Physician-Owned Ambulatory Surgery Facilities Appealed LNRs Requests for Extended Implementation/Performance Period Batching Notifications - Fall March 6, 2019 – March 12, 2019 Need Projection Analyses New Batching Review Winter Cycle Fall Cycle Non-Filed or Incomplete Surveys Georgia Department of Community Health Office of Health Planning Indigent-Charity Shortfalls 2 Peachtree Street 5th Floor CON Filing Requirements (effective July 18, 2017) Atlanta, Georgia 30303-3159 Contact Information (404) 656-0409 (404) 656-0442 Fax Verification of Lawful Presence within U.S. www.dch.georgia.gov Periodic Reporting Requirements CON Thresholds Open Record Request Form Web Links Certificate of Need Appeal Panel www.GaMap2Care.info Letters of Intent LOI2019010 Tanner Imaging Center, Inc. Development of Freestanding Imaging Center on Tanner Medical Center-Carrollton Campus Received: 2/15/2019 Application must be submitted on: 3/18/2019 Site: 706 Dixie Street, Carrollton, GA 30117 (Carroll County) Estimated Cost: $2,200,000 -

Volume 26, Number 3, Summer 2010

Message from the Chair Danny O ’Neal All W e Nee d Is A “F ew G oo d Memb ers ” Volume 2 6, N umber 3 Summer 2010 Hello to every one and “Happy Summer”! I h ope y ou are a ll havin g a wo nd erful sum mer, tho ugh in th e South tha t p retty much me ans he at, humi dity a nd, depend ing on w here y ou Message fr om th e C hair - 1 live, the v ariou s f orces of nat ure. I won ’t m ention the m for Current SC/MLA Officers - 2 fear of invoking their presence. I’ll just wish that we all stay safe from any adverse weather phenomena. Around th e S outh Alabama - 3 For all of you who were not able to atte nd MLA 2010, I do want to sa y that it w as a n exceptional meeting. Whenever I attend a conference I always return to work Florida - 4 pumpe d up and full of ne w ideas to try on pa trons an d col leagues. This year w as no G e o rgia - 1 0 different but as I attended many sessions, speakers, CE’s, and other events my ex - perience was tempered by comparing the scope and quality of MLA against our up - Mississippi - 1 1 coming chapt er meetin g in Novem ber. The re is no thing like participating in a South C arolina - 1 1 process to fully apprec iate the creat ivity, logistic s, time , and energy required to put it together and make it work. -

2019 Cardiovascular Update May 31, 2019

2019 Cardiovascular Update May 31, 2019 Drew Lecture Hall Medical Services Building Piedmont Athens Regional Athens, GA About the Conference Welcome The Georgia Chapter of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) would like to invite you to attend the 2019 Car- diovascular Update. This meeting reflects our dedication to reducing cardiovascular risk and improving patient outcomes. Registered Nurses, Nurse Practitioners, Clinical Nurse Specialists, Physician Assistants, and Clinical Pharmacists should participate in order to enhance their knowledge, improve assessment skills, and network with colleagues. At this meeting, you will have the opportunity to learn more about the latest research and clinical guideline updates in cardiovascular medicine and apply this information to your own clinical practice. We look forward to providing you with an individualized experience that meets all of your learning needs. Kathi Davis, RN, CCCC Program Director About the Conference Parking The conference registration desk will be open from The conference will be held in the Drew 7:00am - 3:00pm on Friday. The program will begin Lecture Hall which is located on the third floor of the promptly at 8:00am and continue until 3:00pm. Medical Services Building (#8 on the map below). You may park in the MSB parking lot and one of the CME All registrants will need to provide their member or non team will validate your parking ticket if needed. member ID# and email address. Each attendee will be sent an evaluation link from [email protected] following the course. Once the evaluation has been completed, you will be prompted to enter your name (as you would like for it to appear on your certificate) and your email address. -

It's About Time... You Knew the Facts. Trauma Care in Georgia

FACT SHEET – GEORGIA It’s About Time... You Knew the Facts. Trauma Care in Georgia • In Georgia, only 15 of the state’s 152 acute-care hospitals are designated trauma centers. • Georgia should have approximately 30 designated trauma centers in strategic locations to adequately address trauma and emergency preparedness needs, according to state health officials. • The 15 current centers are dispersed among ten counties and large areas are not adequately served. Millions of Georgians live and work at least two hours away from timely trauma care, even in urban and suburban areas. • Several Georgia counties still do not have a 911 emergency system. • Of the estimated 40,000 cases of major trauma each year in Georgia, only about 10,000 are treated in designated trauma centers. • Georgia’s trauma death rate is significantly higher than the national average: 63 of every 100,000 people compared to the national average of 56 per 100,000. • If Georgia’s death rate improved to the national average, it would mean a difference of as many as 700 more lives saved every year. • Georgians are four times more likely to die if involved in a vehicular crash in a rural area, than in an urban area, according to Georgia Department of Transportation statistics. State health officials say poor access to trauma centers in rural areas is a major factor. • The state’s first trauma center, Floyd Medical Center, opened in 1981. • In Georgia a “designated” trauma center must voluntarily meet guidelines established by the state and the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma. -

2019 Ambetter and Bluecross Hospital List.Xlsx

Ambetter and BlueCross Hospital List Most doctors that practice at an in‐network hospital will also be in‐network. One exception we know is Piedmont Atlanta Hospital. Piedmont Hospital is in the Ambetter netwok, but very few Piedmont Doctors are. It's always best to check with the insurance company's Search Tool or with the Provider directly. Hospital Name City Zip Ambetter BlueCross Emory University Hospital Atlanta 30322 X Emory University Hospital Midtown Atlanta 30308 X Emory Saint Joseph Atlanta 30342 X Emory Johns Creek Duluth 30097 X Emory Wesley Woods Hospital Atlanta 30329 X Northside Hospital Atlanta 30342 X Northside Hospital Cherokee Canton 30115 X Northside Hospital Forsyth Cumming 30041 X WellStar Atlanta Medical Center Atlanta 30312 X X WellStar Windy Hill Marietta 30067 X X WellStar Cobb Austell 30106 X X WellStar North Fulton Hospital Roswell 30076 X X WellStar Douglas Douglasville 30134 X Wellstar Kennestone Hospital Marietta 30060 X X WellStar Paulding Hiram 30141 X X WellStar Spalding Griffin 30224 X X WellStar Sylvan Grove Jackson 30233 X X WellStar Atlanta Medical Center South East Point 30344 X X Wellstar West Georgia Medical Center Lagrange 30240 X X DeKalb Medical Center Decatur 30033 X X Dekalb Medical Center at Hillendale Lithonia 30058 X X Shepherd Center Atlanta 30305 X X Gwinnett Medical Center Duluth Lawrenceville 30096 X X Gwinnett Medical Center Lawrenceville 30046 X X Childrens Healthcare of Atlanta Scottish Rite Atlanta 30342 X X Children Healthcare of Atl Hughes Spaulding Atlanta 30303 X X Childrens -

Alanna & the Qs

Q LIVE NOVEMBER 2017 Alanna & The Qs Wednesday 1st November // 21:00-22:20 Alanna has over 15 years of professional experience as an events performer, session singer and voice over vocalist. She has appeared on BBC1 and BBC Radio 2, as well as being a featured choral vocalist on the Disney’s Cinderella (2015) soundtrack. She has also worked with an array of producers and recording artists globally which most recently includes Ellie Goulding, Sir Tom Jones, Madonna, Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorrillaz), Will Young and Shane Filan (formerly Westlife). Alanna has thrilled guests with her smooth vocals at wedding and corporate events. Alanna & The Qs have performed across London and prestigious venues in the UK with their soulful and rich sound. Q LIVE NOVEMBER 2017 Rachel Trio Friday 3rd November // 21:00-23:00 Rachel is a highly experienced and sought after session vocalist who has backed up the likes of HURTS, Giles Peterson, Giovanca and Elshay while featuring on many notable releases across the globe including the Radio 1’s Dev. International gigs included The Palm Dubai, The Venetian Macao and Four Seasons Florence along with some of the biggest venues across London and the UK. Rachel has been entertaining globally for over 5 years and can hold crowds of up to 5000+ for huge New Years Eve events and exclusive celebrity wedding and parties. Rachel and her trio perform an upbeat and exciting set full of modern pop and classic songs. Q LIVE NOVEMBER 2017 Florence (7 piece) Friday 3rd November // 23:00-00:20 Florence is a jazz/soul singer with an impressive vocal range inspired from legendary female vocalists such as Aretha Franklin, Eva Cassidy and Martha Reeves. -

Medicare Readmission Chart with September 2012 Update

Medicare Readmission Penalties by Hospital (September Update) Medicare will apply the readmissions penalty to reimbursements beginning on Oct. 1. This chart shows both the original penalties released by Medicare in August and the corrected numbers Medicare released on Sept. 28. Maryland hospitals were not penalized because the state has a unique reimbursement arrangement with Medicare. In addition, hospitals with fewer than 25 cases in each of three categories-- heart failure, heart attack and pneumonia--are exempt from the penalties. These hospitals are noted in the "Penalty Eligibility Status." Source: Kaiser Health News analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Initial Corrected Readmission Readmission Penalty Penalty Change in Penalty Eligibility Hospital Name City State Hospital Referral Region (August) (September) Penalty Status Alabama ANDALUSIA REGIONAL HOSPITAL ANDALUSIA AL Pensacola, FL 0.62% 0.67% 0.05% Enough Cases ATHENS-LIMESTONE HOSPITAL ATHENS AL Huntsville, AL 0.05% 0.06% 0.01% Enough Cases ATMORE COMMUNITY HOSPITAL ATMORE AL Pensacola, FL 0.94% 1.00% 0.06% Enough Cases BAPTIST MEDICAL CENTER EAST MONTGOMERY AL Montgomery, AL 0.37% 0.40% 0.03% Enough Cases BAPTIST MEDICAL CENTER SOUTH MONTGOMERY AL Montgomery, AL 0.71% 0.74% 0.03% Enough Cases BAPTIST MEDICAL CENTER-PRINCETON BIRMINGHAM AL Birmingham, AL 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% Enough Cases BIBB MEDICAL CENTER CENTREVILLE AL Tuscaloosa, AL 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% Enough Cases BROOKWOOD MEDICAL CENTER BIRMINGHAM AL Birmingham, AL 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% Enough Cases -

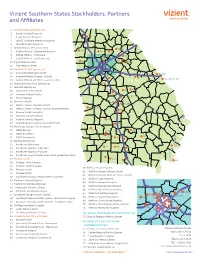

2018 Vizient Southern States Membership Map-Apr

Vizient Southern States Stockholders, Partners and Affiliates 1 Archbold Medical Center, Inc. 2 Brooks County Hospital 18 3 Grady General Hospital 19 16 4 John D. Archbold Memorial Hospital 5 Mitchell County Hospital 6 DeKalb Regional Health System 27, 28 28, 31 10 7 DeKalb Medical - Downtown Decatur 3433 35 30 8 DeKalb Medical - Hillandale 14, 63 33 30 9 DeKalb Medical - North Decatur 11 29 7 10 Floyd Medical Center 66 43 11 Polk Medical Center 12 Gwinnett Health System, Inc. 51, 52, 53 13 Glancy Rehabilitation Center 54, 56 69 14 Gwinnett Medical Center - Duluth 58 15 Gwinnett Medical Center - Lawrenceville 53, 55, 57, 59 70 GEORGIA 16 Hamilton Health Care System, Inc. 68 17 Houston Healthcare 25, 26 25 18 Houston Heart Institute 26 19 Houston Medical Center 24 24, 64 21, 22, 27 20 Perry Hospital 21 Navicent Health 23 17, 18, 19 22 Medical Center, Navicent Health 20, 21, 22 44, 45, 46 23 Medical Center of Peach County, Navicent Health 20 69 24 Monroe County Hospital 73 8, 9, 11, 61 25 Navicent Health Baldwin 23 26 Putnam General Hospital 40 68, 70 10 27 Rehabilitation Hospital, Navicent Health 75 28 Northeast Georgia Health System 29 NGMC Barrow 42 39 62 76 30 NGMC Braselton 66 31 NGMC Gainesville 37, 38 41 50, 52 6774 32 Northside Hospital 36 33 Northside Alpharetta 65 5 72 47, 48 34 Northside Hospital - Cherokee 51 41 34 35 50 35 Northside Hospital - Forsyth 40, 42, 43, 44 36 Northside Hospital Outpatient Center @ Meridian Mark 3 37 Phoebe Health 1, 4 3 260 49 38 Phoebe – Main Campus 6 48 46 39 Phoebe – North Campus 60 WellStar Health