AMS Louisville 2015 Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Leonardoelectronicalma

/ ____ / / /\ / /-- /__\ /______/____ / \ ________________________________________________________________ Leonardo Electronic Almanac volume 11, number 2, February 2003 ________________________________________________________________ ISSN #1071-4391 ____________ | | | CONTENTS | |____________| ________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL --------- by Patrick Lambelet FEATURES -------- < The Scientific and Contemplative Exploration of Consciousness > by B. Alan Wallace < Materialism and the Immaterial Mind in the Ge-luk Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism > by William Magee < Project *Amala*: An Artistic Vision of Consciousness in Buddhism > by Kok Kee Choy < Samadhi: The Contemplation of Space > by Robert C. Morgan < On Audience Awareness: The “Empathy Factor” in the Work of Nell Tenhaaf > by Nina Czegledy LEONARDO DIGITAL REVIEWS ------------------------- < Mirror of Consciousness: Art, Creativity and Veda > Reviewed by Robert Pepperell ISAST NEWS ----------- < OLATS News > ________________________________________________________________ _______________ | | | EDITORIAL | |_______________| ________________________________________________________________ We often discuss consciousness in these pages as if it is a foregone conclusion that we understand what it actually is. By exploring fields such as artificial intelligence, artificial 1 LEONARDOELECTRONICALMANAC VOL 11 NO 2 ISSN 1071-4391 ISBN 978-0-9833571-0-0 life, virtual reality and so on, we may discover and develop sophisticated means of replicating human -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

The Dark Romanticism of Francisco De Goya

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya Elizabeth Burns-Dans The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Burns-Dans, E. (2018). The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya (Master of Philosophy (School of Arts and Sciences)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/214 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i DECLARATION I declare that this Research Project is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which had not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Elizabeth Burns-Dans 25 June 2018 This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence. i ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the enduring support of those around me. Foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Deborah Gare for her continuous, invaluable and guiding support. -

4802170-Ccf435-053479213624.Pdf

1 Suite for Viola and Piano, Op. 8 - Varvara Gaigerova (1903-1944) 1. I. Allegro agitato 2:36 2. II. Andantino 3:06 3. III. Scherzo: Prest 4:25 4. IV. Moderato 4:47 Two Pieces for Viola and Piano, Op.31 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 5. I. Méditation élégiaque (Andante mesto poco mosso) 4:22 6. II. La toupie: scène d’enfant: Scherzino (Allegro vivace) 2:44 Sonata in D Major for Viola and Piano, Op. 15 - Paul Juon (1872-1940) 7. I. Moderato 7:09 8. II. Adagio assai e molto cantabile 6:13 9. III. Allegro moderato 6:50 Sonata in C minor for Viola and Piano, Op. 10 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 10. Moderato 9:59 11. Allegro agitato 6:28 12. L’istesso tempo ma poco rubato 4:24 Variations sur un air breton 13. Thème: Andante 1:06 14. Variation 1: L’istesso tempo poco rubato 1:39 15. Variation 2: Allegretto 1:06 16. Variation 3: Allegro patetico 1:10 17. Variation 4: Andante molto espressivo 1:23 18. Variation 5: Allegro con fuoco 1:18 19. Variation 6: Andante sostenuto 1:47 1 20. Variation 7: Fuga (Allegro moderato) 1:50 21. Coda: Poco più animato - Maestoso pesante 1:05 Total Time 71:02 In the early 20th century, composers Varvara Gaigerova, Alexander Winkler, and Paul Juon, reflect different aspects of Russian music at this historic time of intense social and political revolution. The Russian Revolution of 1905, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, in concert with the complex dynamics involved in the two great World Wars, created instability and hardship for most. -

BOY S GOLD Mver’S Windsong M If for RCA Distribim

Lion, joe f AND REYNOLDS/ BOY S GOLD mver’s Windsong M if For RCA Distribim ARM Rack Jobbe Confab cercise In Commi i cation ista Celebrates 'st Year ith Convention, Concert tal’s Private Stc ijoys 1st Birthd , usexpo Makes I : TED NUGENFS HIGH WIRED ACT. Ted Nugent . Some claim he invented high energy. Audiences across the country agree he does it best. With his music, his songs and his very plugged-in guitar, Ted Nugent’s new album, en- titled “Ted Nugent,” raises the threshold of high energy rock and roll. Ted Nugent. High high volume, high quality. 0n Epic Records and Tapes. High Energy, Zapping Cross-Country On Tour September 18 St. Louis, Missouri; September 19 Chicago, Illinois; September 20 Columbus, Ohio; September 23 Pitts, Penn- sylvania; September 26 Charleston, West Virginia; September 27 Norfolk, Virginia; October 1 Johnson City, Tennessee; Octo- ber 2 Knoxville, Tennessee; October 4 Greensboro, North Carolina; October 5 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; October 8 Louisville, x ‘ Kentucky; October 11 Providence, Rhode Island; October 14 Jonesboro, Arkansas; October 15 Joplin, Missouri; October 17 Lincoln, Nebraska; October 18 Kansas City, Missouri; October 21 Wichita, Kansas; October 24 Tulsa, Oklahoma -j 1 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC-RECORD WEEKLY C4SHBCX VOLUME XXXVII —NUMBER 20 — October 4. 1975 \ |GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW cashbox editorial Executive Vice President Editorial DAVID BUDGE Editor In Chief The Superbullets IAN DOVE East Coast Editorial Director Right now there are a lot of superbullets in the Cash Box Top 1 00 — sure evidence that the summer months are over and the record industry is gearing New York itself for the profitable dash towards the Christmas season. -

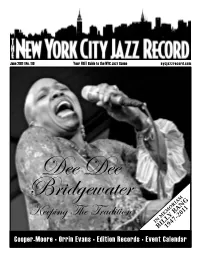

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

The Grateful Dead and the Long 1960S – Syllabus Department of Music, University of California – Santa Cruz, Spring Quarter 2018

Music 80N: The Grateful Dead and the Long 1960s – Syllabus Department of Music, University of California – Santa Cruz, Spring Quarter 2018 Instructor: Dr. Melvin Backstrom [email protected] Teaching Assistants: Marguerite Brown [email protected] Ike Minton [email protected] Class Schedule: MWF, 12pm-1:05pm, Music 101 (Recital Hall) OFFICE HOURS & LOCATION INSTRUCTOR Room 126 Mondays 2-3pm or by appointment TEACHING ASSISTANTS TBA Course Description This music history survey course uses the seminal Bay Area rock band/improvisational ensemble the Grateful Dead as a lens to understand the music and broader history of countercultural music from the 1950s to the present. It combines an extensive engagement with the music of the Grateful Dead, as well as other related musicians, along with a wide variety of readings from non- musical history, political science, philosophy and cultural studies in order to encourage a deep reflection on what the countercultures of the 1960s meant in their heyday, and what their descendants continue to mean today in both musical and non-musical realms. It aims to be both an introduction to those interested in the Grateful Dead, though largely born after the group’s disbandment in 1995, as well as to appeal to those with a broader interest in recent cultural history. Because the University of California – Santa Cruz is the home of the Grateful Dead Archive, students are encouraged to make use of it. However, given the number of students in the course and limitations of UCSC Special Collections its use will not be required. Readings All texts will be available through UCSC’s online system. -

AMS Newsletter August 2015

AMS NEWSLETTER THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY CONSTITUENT MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LEARNED SOCIETIES VOLUME XLV, NUMBER 2 August 2015 ISSN 0402-012X Louisville: City of Surprises AMS Louisville 2015 12–15 November www.ams-net.org/louisville Looee-ville, Louis-ville, Loo-a-ville, Loo-ih- vuhl, Loo-ih-vul . it’s a city of seemingly many names. But to the locals, it’s simply Loo-uh-vul; and one imagines that Louis XVI, after whom the city was named, would probably turn in his grave if he heard it. So would Michelangelo, if he saw the stupen- dous homage to him outside the 21c Museum Hotel, one of the top boutique hotels in the world and only a short walk from Galt House (venue of the AMS meeting). Drenched in mock Cellinian splendor (and somehow al- ways free of avian donations despite its being The Belle of Louisville on the Ohio River permanently placed outside), it’s truly a sight see in this city by the river (the red glass gems- House is Fourth Street Live!, a focal point for to behold. encrusted limousine by the hotel entrance, so nighttime entertainment (and the location But 21c’s always captivating art exhibition, dressed up as to be inspired by the interior for our Friday night dance: see p. 18). For the whether indoors or outdoors, is only one of of a pomegranate, is another eye-catcher). more adventurous, there’s the Urban Bour- the many things that a visitor would want to As huge as the homage to Michelangelo is, it bon Trail that leads to the many scattered dis- pales beside the baseball bat that stands taller tilleries (such as Maker’s Mark and Jim Beam) In This Issue… than the five-story Slugger Museum on which for which Kentucky is known. -

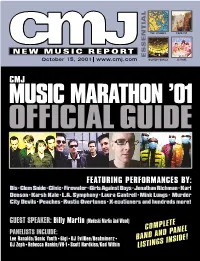

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Lecture Slides

Lunch Lecture Inter-Actief will start at 12:50 ;lkj;lkj;lkj Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (orchestration: Maurice Ravel) Klaas Sikkel Münchner PhilharmonikerInter-Actief lunch conducted lecture, 15 Dec 2020 by Valery Gergiev 1 Pictures at an Exhibition and the Music of the Mighty Handful Inter-Actief Lunch Lecture 15 December 2020 Klaas Sikkel Muziekbank Enschede For Spotify playlist and more info see my UT home page (google “Klaas Sikkel”) Purpose of this lecture • Tell an entertaining story about a fragment of musical history • (hopefully) make you aware that classical music isn’t as boring as you thought, (possibly) raise some interest in this kind of music • Not a goal: make you a customer of the Muziekbank (instead, check out the Spotify playlist) Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 3 Classical Music in Russia around 1860 Two persons have contributed greatly to professionalization and practice of Classical Music in Russia: • Anton Rubinstein (composer, conductor, pianist) 4 Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 Classical Music in Russia around 1860 Two persons have contributed greatly to professionalization and practice of Classical Music in Russia: • Anton Rubinstein (composer, conductor, pianist) • Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna (aunt of Tsar Alexander II, patroness) 5 Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 Classical Music in 1859 Russia around 1860 Founding of the Two persons have contributed Russian greatly to professionalization and Musical Society practice of Classical