Bisexuality Is Queer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: an Argument from Bisexuality

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2012 Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality Michael Boucai University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Michael Boucai, Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality, 49 San Diego L. Rev. 415 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality MICHAEL BOUCAI* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................416 II. SEXUAL LIBERTY AND SAME-SEX MARRIAGE .............................. 421 A. A Right To Choose Homosexual Relations and Relationships.........................................421 B. Marriage'sBurden on the Right............................426 1. Disciplineor Punishment?.... 429 2. The Burden's Substance and Magnitude. ................... 432 III. BISEXUALITY AND MARRIAGE.. ......................................... -

Nepantla.Issue3 .Pdf

Nepantla A Journal Dedicated to Queer Poets of Color Editor-In-Chief Christopher Soto Manager William Johnson Cover Image David Uzochukwu Welcome to Nepantla Issue #3 Wow! I can't believe this is already the third year of Nepantla's existence. It feels like just the other day when I only knew a handful of queer poets of color and now my whole life is surrounded by your community. Thank you for making this journal possible! This year, we read thousands of poems to consider for publication in Nepantla. We have published twenty-seven poets below (three of them being posthumous publications). It's getting increasingly more difficult to publish all of the amazing poems we encounter during the submissions process. Please do not be discouraged from submitting to us multiple years! This decision, to publish posthumously, was made in a deep desire to carry the legacies of those who have helped shape our understandings of self and survival in the world. With Nepantla we want to honor those who have proceeded us and honor those who are currently living. We are proud to be publishing the voices of June Jordan, Akilah Oliver, and tatiana de la tierra in Issue #3. This year's issue was made possible by a grant from the organization 'A Blade of Grass.' Also, I want to acknowledge other queer of color journals that have formed in the recent years too. I believe that having a multitude of journals, and not a singular voice, for our community is extremely important. Oftentimes, people believe in a destructive competition which doesn't allow for their communities to flourish. -

Bisexual Crime Victims: Least Visible, Most at Risk

Bisexual Crime Victims: Least Visible, Most at Risk Loree Cook-Daniels and michael munson July 2019 forge-forward.org Thank you OVC ! This training was produced by FORGE under 2016- XV-GX-K015, awarded by the Office for Victims of Crime, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this training are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. forge-forward.org Welcome & Housekeeping • Take care of yourself • PPTs 3 forge-forward.org FORGE Webinar Leads Loree Cook-Daniels michael munson Policy & Program Director Executive Director 4 forge-forward.org FORGE’s Role in Resource Center • One of eight population groups • FORGE leads the LGBTQ working group • National transgender anti-violence group • Headquartered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin Facebook Twitter Instagram 5 forge-forward.org Agenda • Makeup of the LGBTQ community • Bisexuality: Definitions and Data • Invisibility • Disparities (victimization, health, other) • Best or worst of both worlds? • Service provider barriers • What providers can do to help • Take home messages 6 forge-forward.org Makeup of U.S. LGB Community 7 forge-forward.org 2015 White House Bisexual Community Policy Briefing 8 forge-forward.org Definitions and Data forge-forward.org What about trans people and gender diversity? forge-forward.org Our definition of bisexual A person who is romantically and/or sexually attracted to individuals of their own gender and to individuals of other genders. forge-forward.org “I call myself bisexual because I acknowledge that I have in myself the potential to be attracted – romantically and/or sexually – to people of more than one sex and/or gender, not necessarily at the same time, not necessarily in the same way, and not necessarily to the same degree.” 12 forge-forward.org U.S. -

Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2017 Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States Royal Gene Cravens III University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Cravens, Royal Gene III, "Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4453 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Royal Gene Cravens III entitled "Politics at the Intersection of Sexuality: Examining Political Attitudes and Behaviors of Sexual Minorities in the United States." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Anthony J. Nownes, Major Professor -

SPR2013 SOC200 Syllabus DRAFT.Docx

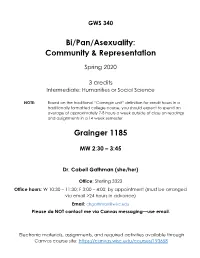

GWS 340 Bi/Pan/Asexuality: Community & Representation Spring 2020 3 credits Intermediate; Humanities or Social Science NOTE: Based on the traditional “Carnegie unit” definition for credit hours in a traditionally formatted college course, you should expect to spend an average of approximately 7-8 hours a week outside of class on readings and assignments in a 14-week semester Grainger 1185 MW 2:30 – 3:45 Dr. Cabell Gathman (she/her) Office: Sterling 3323 Office hours: W 10:30 – 11:30; F 3:00 – 4:00; by appointment (must be arranged via email >24 hours in advance) Email: [email protected] Please do NOT contact me via Canvas messaging—use email. Electronic materials, assignments, and required activities available through Canvas course site: https://canvas.wisc.edu/courses/193658 – 2 – Course Description Bisexual/biromantic, pansexual/panromantic, and asexual/aromantic (BPA) people are often denied (full) membership in the "queer community," or assumed to have the same experiences and concerns as lesbian and gay (LG) people and thus not offered targeted programs or services. Recent research has shown a wide variety of negative outcomes experienced by bisexual/biromantic people at much higher rates than LG people, and still barely acknowledges the existence of pansexual/panromantic or asexual/aromantic people. (Although research differentiating pan and bi people is still quite sparse, what exists suggests that systematic differences may exist between these groups, as well.) This course builds on concepts and information covered in Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies (GWS 200). It will explore the experiences, needs, and goals of BPA people, as well as their interactions with the mainstream lesbian & gay community and overlap and coalition building with other marginalized groups. -

June Jordan's Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler in Her Poetry, the Late African Am

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 38 (2013): 65-82 “I am she who will be free”: June Jordan’s Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler In her poetry, the late African American writer June Jordan (1936- 2002) approaches cultural disputes, violent conflicts, as well as transnational issues of equality and inclusion from an all-encompassing, global angle. Her rather singular way of connecting feminism, female sexual identity politics, and transnational issues from wars to foreign policy facilitates an investigation of the role of poetry in the context of Transnational Feminisms at large. The transnational quality of her literary oeuvre is not only evident thematically but also in her style and her use of specific poetic forms that encourage cross-cultural dialogue. By “mapping connections forged by different people struggling against complex oppressions” (Friedman 20), Jordan becomes part of a multicultural feminist discourse that takes into account the context-dependency of oppressions, while promoting relational ways of thinking about identity. Through forging links and loyalties among diverse groups without silencing the complexities and historical specificities of different situations, her writing inspires a “polyvocal” (Mann and Huffmann 87) feminism that moves beyond fixed categories of race, sex and nation and that works towards a more “relational” narration of conflicts and oppressions across the globe (Friedman 40). Jordan’s poetry consciously reflects upon the experience of being female, black, bisexual, and American. Thus, her work speaks from an angle that is at the same time dominant and marginal. To put it in her own words: “I am Black and I am female and I am a mother and I am a bisexual and I am a nationalist and I am an antinationalist. -

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms Mollie Blackburn Mary Catherine Miller Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Art Classrooms KEY TERMS Equity Assistance Centers (EACs) are charged with providing technical assistance, LGBTQ - The acronym used to represent lesbian, gay, including training, in the area of sex bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning identities and desegregation, among other areas of themes. We recognize that this acronym excludes some desegregation, of public elementary and people, like those who are asexual or intersex, but we aim to secondary schools. Sex desegregation, here, be honest about who gets featured in literature representing sexual and gender minorities. means the “assignment of students to public schools and within those schools without regard Gender - While “sex” is the biological differentiation of being to their sex including providing students with a male or female, gender is the social and cultural presentation full opportunity for participation in all of how an individual self-identifies as masculine, feminine, or within a rich spectrum of identities between the two. Gender educational programs regardless of their roles are socially constructed, and typically reinforced in a sex” (https://www.federalregister.gov/ gender binary that places masculine and feminine roles in documents/2016/03/24/2016-06439/equity- opposition to each other. assistance-centers-formerly-desegregation- Cisgender - An individual who identifies as the gender assistance-centers). This is pertinent to LGBTQ corresponding with the sex they were assigned at birth students. Most directly, students who identify as (Aultman, 2014; Stryker, 2009). By using cisgender to trans or gender queer are prevented from distinguish someone as not transgender, the term “helps attending school because of the transphobia distinguish diverse sex/gender identities without reproducing they experience there. -

Ways to Be an Ally to Nonmonosexual / Bi People

Ways To Be An Ally to Nonmonosexual / Bi People The ideas in this pamphlet were generated during a discussion at a UC Davis Bi Visibility Project group meeting and were compiled Winter quarter, 2009. Nonmonosexual / bisexual individuals self-identify in a variety of different ways – please keep in mind that though this pamphlet gives suggestions about how to be a good ally, one of the most important aspects of being an ally is respecting individual’s decisions about self-identification. There are hundreds of ways to be a good ally – Please use these suggestions as a starting point, and seek additional resources! In this pamphlet the terms “bisexual” and “nonmonosexual” will be used Monosexism: a belief that monosexuality interchangeably to describe individuals who (either exclusive heterosexuality and/or identify with nonmonosexual orientations being lesbian or gay) is superior to a (attracted to more than one gender), bisexual or pansexual orientation. encompassing pan-, omni-, ambi-, bi-, and <http://www.wikipedia.com> nonmonosexual identities. Respect personal choices about self-identification and use specific terms on an individual basis. Try… Acknowledging that a person who is bisexual is always bisexual regardless of their current or past partner(s) or sexual experience(s). Using the terms, “monosexual” and “monosexism.” Educating yourself through articles, books, websites or other resources if you have questions. Questioning the negativity associated with bisexual stereotypes. Example: The stereotype that “all bi people are oversexed.” This reinforces societal assumptions about the nature of “good” or “appropriate” sexual practice or identity. Acknowledge the different ways women, people of color, disabled people, queer people and all intersections thereof, are eroticized or criticized for being sexual. -

Queer Politics, Bisexual Erasure: Sexuality at the Nexus of Race, Gender, and Statistics

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Queer Politics, Bisexual Erasure: Sexuality at the Nexus of Race, Gender, and Statistics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8hv987pn Author Rodriguez, JM Publication Date 2021-06-27 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California JUANA MARÍA RODRÍGUEZ Queer Politics, Bisexual Erasure Sexuality at the Nexus of Race, Gender, and Statistics COMING OF AGE as a bisexual Latina femme in the 1980s, I was sur- rounded by lesbian-feminist communities and discourses that dispar- aged, dismissed, and vilified bisexuality. Those of us that enthusiastically embraced femininity or that actively sought out masculine presenting butches, were deemed perpetually suspect. Femmes were imagined as being always on the verge of abandoning the lesbian-feminist commu- nities that nurtured us for the respectability and privilege that hetero- sexual relations might afford. The label bisexuality, for those that dared to claim it, was viewed as the apolitical cop-out for those that were not radical enough to fully commit to the implied lesbian practice of feminist theory. In the bad old days of lesbian separatist politics, bisexu- ality was attached to a yearning, not just for men, but for multifarious sexual pleasures deemed decidedly anti-feminist including desires for penetration, sexual dominance and submission, and the wickedly per- verse delights of expressive gender roles. Decades later, discursive prac- tices have shifted. The B is now routinely added to the label LGBT and the umbrella of queer provides discursive cover for sexual practices that fall outside the normative frameworks of heteropatriarchy. -

Hopelessly/Helplessly?)To Labels That Rust, Paula and C

my sexuality is whole. I am not York: Simon and Schuster, 1996. You're a fence-sitter. We're all straight with men and lesbian Hutchins, Loraine and Lani waiting for you to come out with women; I am bisexual with Kaahumanu. Bi Any Other Name. come down. We're all waiting both. (qtd. in Pramagiorre and Los Angeles: Alyson Books, 1991. for you. (Carlton 14) Pramagiorre 161). Murphy, Marilyn. "Thinking About Bisexuality." Resourcesfor Feminist I guess, in retrospect, it's the notion So I am in a monogamous, com- Research 19 (314) (1990): 87-88. of this last opinion that I find the mitted relationshipwith a man. "Not Papazian, Ellen. "Woman on the most bitter pill to swallow, although muchofa bisexual yousay" (Yoshizaki Verge." Ms. Magazine (November1 I would be lying if I said it didn't qtd. in Hutchins etal. 25). However, December 1996): 38-45. resonate to some degree. for me I am. More than being about Pramagiorre, Donald E. and Maria the "au courant," bisexuality has Pramagiorre, eds. Representing Sometimes I think I'm only allowed me to better understand my Bisexualities. New York: New York bisexual in that "not lesbian potential. Even if I am still clutching University Press, 1996. enuf' kind of way. (Crago 15) (hopelessly/helplessly?)to labels that Rust, Paula and C. Rust. Bisexuality stay firmly "within the box," this andthe Challenge to Lesbian Politics. Conclusions? notion of bisexual "possibilities" has New York: New York University allowed me to understand that being Press, 1995. If only I had come to some bisexual can have more to do with Sinclair, April. -

Novel Approaches to Negotiating Gender and Sexuality in the Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The olorC Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Selha, A. D., "Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The oC lor Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues" (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 9. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -r Distracting the border guards: Novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies Major Professor: Kathy Hickok Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1997 1 ii JJ Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of A.D. Selha has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University 1 1 11 iii DEDICATION For those who have come before me, I request your permission to write in your presence, to illuminate your lives, and draw connections between the communities which you may have painfully felt both a part of and apart from. -

A Review of Cigarettes & Wine, JE Sumerau (Sense Publishers, 2017)

Journal of Bisexuality ISSN: 1529-9716 (Print) 1529-9724 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wjbi20 Until It Gets Better: A Review of Cigarettes & Wine, J. E. Sumerau (Sense Publishers, 2017) Loraine Hutchins To cite this article: Loraine Hutchins (2017) Until It Gets Better: A Review of Cigarettes & Wine, J. E. Sumerau (Sense Publishers, 2017), Journal of Bisexuality, 17:3, 374-376, DOI: 10.1080/15299716.2017.1362915 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2017.1362915 Published online: 05 Sep 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 25 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wjbi20 Download by: [University of Tampa] Date: 28 September 2017, At: 20:50 JOURNAL OF BISEXUALITY 2017, VOL. 17, NO. 3, 374–376 BI BOOK REVIEW Until It Gets Better: A Review of Cigarettes & Wine, J. E. Sumerau (Sense Publishers, 2017) “To those who embody sexual and gender fluidity in a world that seeks to erase us.…” (Cigarettes & Wine, dedication page) Cigarettes & Wine evokes mind-altering and relaxing substances teens often sample when first navigating the uncertain shoals of sexual intimacy. The sensations and memories of sharing smokes and sipping alcohol are so intertwined with the early sexual memories of many of us that it is impossible to separate them from the experience. I put my aversion to tobacco smoke aside to read this absorbing novel, remembering how romanticized smoking was when as, as a youth, I first encountered the sensory inhalation as a sign of freedom and independence of beginning adulthood, “We drank wine, she smoked cigarettes, and we began the process of saying goodbye to our time as childhood neighbors without a care in the world” (p.