Class-Race-Gender: Sloganeering in Search of Meaning. by Kathleen Daly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missing from the Map: Feminist Theory and the Omission of Jewish Women Jennifer Roskies Researcher, ISGAP and Bar-Ilan Universit

1 Missing from the Map: Feminist Theory and the Omission of Jewish Women Jennifer Roskies Researcher, ISGAP and Bar-Ilan University [email protected] The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series. Working Paper Roskies 2010 ISSN: 1940-610X © The Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and PolicyISBN: 978-0-9819058-6-0 Series Editor Charles Asher Small ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second Floor New York, NY 10022 United States www.isgap.org 2 ABSTRACT This paper examines an apparent omission within feminist theory. Feminists of diverse cultural backgrounds have developed theoretical models which articulate their respective standpoints in relation to the sexism of their racial/ethnic groups on the one hand, and what has been termed “mainstream” or “white” feminism on the other. This is not the case when it comes to multicultural and ethnographic research regarding Jewish women, notwithstanding the involvement of many Jewish women in the feminist movement generally, including as leading theorists. Would a body of scholarship which examines Jewish women’s experiences from this dual perspective uncover a distinct theoretical model? How would such a “feminist Jewish women’s standpoint” address their concerns within the Jewish world as well as within the world of mainstream feminism – such as expressions within the mainstream women’s movement that pertain to Jewish issues or Israel? In examining the possible origins of the existing asymmetry, as well as its implications, this paper explores the possibility of adding new dimensions to understanding of multicultural feminism, identity studies and the study of Jewish identity. -

A Classification of Feminist Theories Karen Wendling

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 15:45 Les ateliers de l'éthique The Ethics Forum A Classification of Feminist Theories Karen Wendling Volume 3, numéro 2, automne 2008 Résumé de l'article Une analyse critique de la description des théories politiques féministes révèle URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1044593ar qu’une classification alternative à celle de Jaggar permettrait de répertorier DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1044593ar plus adéquatement les différents courants féministes qui ont évolués au cours des dernières décennies. La nouvelle cartographie que nous proposons Aller au sommaire du numéro comprend deux familles de féminisme : activiste et académique. Cette nouvelle manière de localiser et situer les féminismes aide à comprendre pourquoi il n’y a pas de féminisme radical à l’extérieur de l’Amérique du Nord et aussi Éditeur(s) pourquoi il y a si peu de féministes socialistes en Amérique du Nord. Dans ce nouveau schème, le féminisme de la « différence » devient une sous-catégorie Centre de recherche en éthique de l’Université de Montréal du féminisme activiste car ce courant a eu une influence importante sur le féminisme activiste. Même si les courants de féminisme académique n’ont pas ISSN de rapports directs avec les mouvements activistes, ils jouent un rôle important dans l’énonciation et l’élaboration de certaines problématiques qui, ensuite, 1718-9977 (numérique) peuvent s’avérer cruciales pour les activistes. Nous concluons en démontrant que cette nouvelle classification représente plus clairement les différents Découvrir la revue féminismes et facilite la compréhension de l’évolution du féminisme et des enjeux qui ont influencé le féminisme. -

Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: an Argument from Bisexuality

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2012 Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality Michael Boucai University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Michael Boucai, Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality, 49 San Diego L. Rev. 415 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality MICHAEL BOUCAI* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................416 II. SEXUAL LIBERTY AND SAME-SEX MARRIAGE .............................. 421 A. A Right To Choose Homosexual Relations and Relationships.........................................421 B. Marriage'sBurden on the Right............................426 1. Disciplineor Punishment?.... 429 2. The Burden's Substance and Magnitude. ................... 432 III. BISEXUALITY AND MARRIAGE.. ......................................... -

Global Feminism, Comparatism, and the Master's Tools

15 Compared to What? Global Feminism, Comparatism, and the Master's Tools SUSAN SNIADER LANSER And rain is the very thing that you, just now, do not want, for you are thinking of the hard and cold and dark and long days you spent working in North America (or, worse, Europe), earning some money so that you could stay in this place (Antigua) where the sun always shines and where the climate is deliciously hot and dry ...and since you are on your holiday, since you are a tourist, the thought of what it might be like for someone who had to live day in, day out in a place that suffers constantly from drought ...must never cross your mind. And you leave, and from afar you watch as we do to ourselves the very things you used to do to us. And you might feel that there was more to you than that, you might feel that you had understood the meaning of the Age of Enlightenment (though, as far as I can see, it has done you very little good); you loved knowl edge, and wherever you went you made sure to build a school, a library (yes, and in both of these places you distorted or erased my history and glorified your own). As for what we were like before we met you, I no longer care. No periods of time over which my ancestors held sway, no doc umentation of complex civilisations, is any comfort to me. Even if I really came from people who were living like monkeys in trees, it was better to be that than what happened to me, what I became after I met you. -

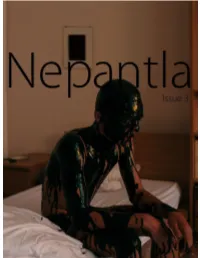

Nepantla.Issue3 .Pdf

Nepantla A Journal Dedicated to Queer Poets of Color Editor-In-Chief Christopher Soto Manager William Johnson Cover Image David Uzochukwu Welcome to Nepantla Issue #3 Wow! I can't believe this is already the third year of Nepantla's existence. It feels like just the other day when I only knew a handful of queer poets of color and now my whole life is surrounded by your community. Thank you for making this journal possible! This year, we read thousands of poems to consider for publication in Nepantla. We have published twenty-seven poets below (three of them being posthumous publications). It's getting increasingly more difficult to publish all of the amazing poems we encounter during the submissions process. Please do not be discouraged from submitting to us multiple years! This decision, to publish posthumously, was made in a deep desire to carry the legacies of those who have helped shape our understandings of self and survival in the world. With Nepantla we want to honor those who have proceeded us and honor those who are currently living. We are proud to be publishing the voices of June Jordan, Akilah Oliver, and tatiana de la tierra in Issue #3. This year's issue was made possible by a grant from the organization 'A Blade of Grass.' Also, I want to acknowledge other queer of color journals that have formed in the recent years too. I believe that having a multitude of journals, and not a singular voice, for our community is extremely important. Oftentimes, people believe in a destructive competition which doesn't allow for their communities to flourish. -

Modernity, Marginality, and Redemption: German and Jewish Identity at the Fin-De-Siècle

MODERNITY, MARGINALITY, AND REDEMPTION: GERMAN AND JEWISH IDENTITY AT THE FIN-DE-SIÈCLE Richard V. Benson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Dr. Jonathan Hess (Advisor) Dr. Jonathan Boyarin Dr. William Collins Donahue Dr. Eric Downing Dr. Clayton Koelb © 2009 Richard V. Benson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Richard Benson Modernity, Marginality, and Redemption: German and Jewish Identity at the Fin-de-Siècle (Under the direction of Dr. Jonathan Hess) Modernity, Marginality, and Redemption: German and Jewish Identity at the Fin-de-Siècle explores the literary, cultural, and historical process of negotiating German-Jewish identity following the radical restructuring of German-Jewish society during the nineteenth century. Modernity, Marginality, and Redemption considers the dynamic cultural roles that writers such as Karl Emil Franzos, Martin Buber, Jakob Wassermann, Theodor Herzl, and others assigned to the image of East European Jewry and of ghetto life, to Chassidic mysticism, and to messianic historical figures. I show that the works of these authors enact a self-conscious reinvention of Jewish tradition, which weds Enlightenment ideals with aspects of Jewish tradition that the Enlightenment had marginalized, while also engaging in dialogue with the most pressing discourses of fin-de-siècle European culture, in order to proffer Jewish identities that are neither strictly national nor simply religious. As I demonstrate, these texts establish Jewish identity as a central coordinate in debates about nationalism, the limits of language, phenomenology, social progress, and cultural degeneration. -

SPR2013 SOC200 Syllabus DRAFT.Docx

GWS 340 Bi/Pan/Asexuality: Community & Representation Spring 2020 3 credits Intermediate; Humanities or Social Science NOTE: Based on the traditional “Carnegie unit” definition for credit hours in a traditionally formatted college course, you should expect to spend an average of approximately 7-8 hours a week outside of class on readings and assignments in a 14-week semester Grainger 1185 MW 2:30 – 3:45 Dr. Cabell Gathman (she/her) Office: Sterling 3323 Office hours: W 10:30 – 11:30; F 3:00 – 4:00; by appointment (must be arranged via email >24 hours in advance) Email: [email protected] Please do NOT contact me via Canvas messaging—use email. Electronic materials, assignments, and required activities available through Canvas course site: https://canvas.wisc.edu/courses/193658 – 2 – Course Description Bisexual/biromantic, pansexual/panromantic, and asexual/aromantic (BPA) people are often denied (full) membership in the "queer community," or assumed to have the same experiences and concerns as lesbian and gay (LG) people and thus not offered targeted programs or services. Recent research has shown a wide variety of negative outcomes experienced by bisexual/biromantic people at much higher rates than LG people, and still barely acknowledges the existence of pansexual/panromantic or asexual/aromantic people. (Although research differentiating pan and bi people is still quite sparse, what exists suggests that systematic differences may exist between these groups, as well.) This course builds on concepts and information covered in Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies (GWS 200). It will explore the experiences, needs, and goals of BPA people, as well as their interactions with the mainstream lesbian & gay community and overlap and coalition building with other marginalized groups. -

June Jordan's Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler in Her Poetry, the Late African Am

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 38 (2013): 65-82 “I am she who will be free”: June Jordan’s Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler In her poetry, the late African American writer June Jordan (1936- 2002) approaches cultural disputes, violent conflicts, as well as transnational issues of equality and inclusion from an all-encompassing, global angle. Her rather singular way of connecting feminism, female sexual identity politics, and transnational issues from wars to foreign policy facilitates an investigation of the role of poetry in the context of Transnational Feminisms at large. The transnational quality of her literary oeuvre is not only evident thematically but also in her style and her use of specific poetic forms that encourage cross-cultural dialogue. By “mapping connections forged by different people struggling against complex oppressions” (Friedman 20), Jordan becomes part of a multicultural feminist discourse that takes into account the context-dependency of oppressions, while promoting relational ways of thinking about identity. Through forging links and loyalties among diverse groups without silencing the complexities and historical specificities of different situations, her writing inspires a “polyvocal” (Mann and Huffmann 87) feminism that moves beyond fixed categories of race, sex and nation and that works towards a more “relational” narration of conflicts and oppressions across the globe (Friedman 40). Jordan’s poetry consciously reflects upon the experience of being female, black, bisexual, and American. Thus, her work speaks from an angle that is at the same time dominant and marginal. To put it in her own words: “I am Black and I am female and I am a mother and I am a bisexual and I am a nationalist and I am an antinationalist. -

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms Mollie Blackburn Mary Catherine Miller Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Art Classrooms KEY TERMS Equity Assistance Centers (EACs) are charged with providing technical assistance, LGBTQ - The acronym used to represent lesbian, gay, including training, in the area of sex bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning identities and desegregation, among other areas of themes. We recognize that this acronym excludes some desegregation, of public elementary and people, like those who are asexual or intersex, but we aim to secondary schools. Sex desegregation, here, be honest about who gets featured in literature representing sexual and gender minorities. means the “assignment of students to public schools and within those schools without regard Gender - While “sex” is the biological differentiation of being to their sex including providing students with a male or female, gender is the social and cultural presentation full opportunity for participation in all of how an individual self-identifies as masculine, feminine, or within a rich spectrum of identities between the two. Gender educational programs regardless of their roles are socially constructed, and typically reinforced in a sex” (https://www.federalregister.gov/ gender binary that places masculine and feminine roles in documents/2016/03/24/2016-06439/equity- opposition to each other. assistance-centers-formerly-desegregation- Cisgender - An individual who identifies as the gender assistance-centers). This is pertinent to LGBTQ corresponding with the sex they were assigned at birth students. Most directly, students who identify as (Aultman, 2014; Stryker, 2009). By using cisgender to trans or gender queer are prevented from distinguish someone as not transgender, the term “helps attending school because of the transphobia distinguish diverse sex/gender identities without reproducing they experience there. -

Beck VITA Rev January 2018

January 2018 EVELYN TORTON BECK, Ph.D. Professor Emerita, Women’s Studies, University of Maryland; Alum Research Fellow, Creative Longevity and Wisdom Initiative, The Fielding Graduate University [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. (Clinical Psychology) 2004 The Fielding Graduate University Ph.D. (Comparative Literature) 1969 University of Wisconsin-Madison M.A. 1955 Yale University B.A. 1954 Brooklyn College ACADEMIC TEACHING POSITIONS 2002—Professor Emerita, University of Maryland-College Park 1984–2002 Professor, Women's Studies Department, Affiliate Professor of Comparative Literature, German, and Jewish Studies, University of Maryland-College Park 1984-93 Director, Women's Studies Program, University of Maryland-College Park 1982-84 Professor, Comparative Literature, German and Women's Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1981-82 Jane Watson Irwin Visiting Professor of Comparative Literature and Women's Studies, Hamilton College 1977-82 Associate Professor, Comparative Literature, German and Women's Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1972-77 Assistant Professor, Comparative Literature, German and Women's Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1970-72 Lecturer, Comparative Literature, University of Maryland-College Park Selected HONORS AND AWARDS Frieda-Fromm Reichmann Dissertation Award, Fielding Graduate University, 2004 Alum “Fellow” Creative Longevity and Wisdom Project, The Fielding Graduate University, 2005 - present Distinguished Scholar/Teacher, University of Maryland, 1995-96 Outstanding Woman of the Year, University of Maryland, 1993 Outstanding Alum, University of Wisconsin, Gay/Lesbian Alums, 1993 National Endowment for the Humanities, Research Fellowship, 1983-84; 1973 American Council of Learned Societies, l97l-72 BOOKS Physical Illness, Psychological Woundedness and the Healing Power of Art in the Life and Work of Franz Kafka and Frida Kahlo, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Fielding Graduate University, 2004. -

Goddess and God in the World

Contents Introduction: Goddess and God in Our Lives xi Part I. Embodied Theologies 1. For the Beauty of the Earth 3 Carol P. Christ 2. Stirrings 33 Judith Plaskow 3. God in the History of Theology 61 Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow 4. From God to Goddess 75 Carol P. Christ 5. Finding a God I Can Believe In 107 Judith Plaskow 6. Feminist Theology at the Center 131 Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow 7. Answering My Question 147 Carol P. Christ 8. Wrestling with God and Evil 171 Judith Plaskow Part II. Theological Conversations 9. How Do We Think of Divine Power? 193 (Responding to Judith’s Chapters in Part 1) Carol P. Christ 10. Constructing Theological Narratives 217 (Responding to Carol’s Chapters in Part 1) Judith Plaskow 11. If Goddess Is Not Love 241 (Responding to Judith’s Chapter 10) Carol P. Christ 12. Evil Once Again 265 (Responding to Carol ’s Chapter 9) Judith Plaskow 13. Embodied Theology and the 287 Flourishing of Life Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow List of Publications: Carol P. Christ 303 List of Publications: Judith Plaskow 317 Index 329 GODDESS AND GOD IN THE WORLD Sunday school lack a vocabulary for intelligent discussion of religion. Without new theological language, we are likely to be hesitant, reluctant, or unable to speak about the divinity we struggle with, reject, call upon in times of need, or experience in daily life. Yet ideas about the sacred are one of the ways we orient ourselves in the world, express the values we consider most important, and envision the kind of world we would like to bring into being. -

Novel Approaches to Negotiating Gender and Sexuality in the Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The olorC Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Selha, A. D., "Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The oC lor Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues" (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 9. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -r Distracting the border guards: Novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies Major Professor: Kathy Hickok Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1997 1 ii JJ Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of A.D. Selha has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University 1 1 11 iii DEDICATION For those who have come before me, I request your permission to write in your presence, to illuminate your lives, and draw connections between the communities which you may have painfully felt both a part of and apart from.