Introduction (Part 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing the Radical in Antisexist and Antiracist Work

The Seneca Falls Dialogues Journal Volume 3 Race and Intersecting Feminist Futures Article 4 2021 Doing the *: Performing the Radical in Antisexist and Antiracist Work Barbara LeSavoy The College at Brockport, State University of New York, [email protected] Angelica Whitehorne The College at Brockport, [email protected] Jasmine Mohamed [email protected] Mackenzie April [email protected] Kendra Pickett The College at Brockport, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sfd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Repository Citation LeSavoy, Barbara; Whitehorne, Angelica; Mohamed, Jasmine; April, Mackenzie; and Pickett, Kendra (2021) "Doing the *: Performing the Radical in Antisexist and Antiracist Work," The Seneca Falls Dialogues Journal: Vol. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sfd/vol3/iss1/4 This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sfd/vol3/iss1/4 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Doing the *: Performing the Radical in Antisexist and Antiracist Work Abstract The essay summarizes excerpts from the 6th Biennial Seneca Falls Dialogue’s (SFD) session, “Doing the *: Performing the Radical in Antisexist and Antiracist Work.” In this dialogue, students read, displayed, or performed excerpts from feminist manifestos that they authored in a -

The Digital Afterlives of This Bridge Called My Back: Woman of Color Feminism, Digital Labor, and Networked Pedagogy Cassius

American Literature Cassius The Digital Afterlives Adair of This Bridge Called My Back: and Woman of Color Feminism, Digital Labor, Lisa and Networked Pedagogy Nakamura Abstract This article traces the publication history of the canonical woman of color feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back through its official and unofficial editions as it has migrated from licensed paper to PDF format. The digital edition that circulated on the social blogging platform Tumblr.com and other informal social networks constitutes a new and impor- tant form of versioning that reaches different audiences and opens up new pedagogical opportu- nities. Though separated by decades, Tumblr and This Bridge both represent vernacular pedagogy networks that value open access and have operated in opposition to hierarchically controlled con- tent distribution and educational systems. Both analog and digital forms of open-access woman of color pedagogy promote the free circulation of knowledge and call attention to the literary and social labor of networked marginalized readers and writers who produce it, at once urging new considerations of academic labor and modeling alternatives to neoliberal university systems. Keywords digital pedagogy, social media, free labor, publishing, open access, Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga Despite encountering the book more than two decades apart, both authors of this article view the edited collection This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (Mor- aga and Anzaldúa 1981) as a cornerstone of our feminist conscious- ness. Perhaps this is not surprising: published in 1981 by the collec- tively run woman of color press Kitchen Table, This Bridge is now countercultural canon, one of many radical interventions into white feminist theory that now undergirds much intersectional work on gender, race, class, and homophobia. -

Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: an Argument from Bisexuality

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2012 Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality Michael Boucai University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Michael Boucai, Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality, 49 San Diego L. Rev. 415 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality MICHAEL BOUCAI* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................416 II. SEXUAL LIBERTY AND SAME-SEX MARRIAGE .............................. 421 A. A Right To Choose Homosexual Relations and Relationships.........................................421 B. Marriage'sBurden on the Right............................426 1. Disciplineor Punishment?.... 429 2. The Burden's Substance and Magnitude. ................... 432 III. BISEXUALITY AND MARRIAGE.. ......................................... -

Nepantla.Issue3 .Pdf

Nepantla A Journal Dedicated to Queer Poets of Color Editor-In-Chief Christopher Soto Manager William Johnson Cover Image David Uzochukwu Welcome to Nepantla Issue #3 Wow! I can't believe this is already the third year of Nepantla's existence. It feels like just the other day when I only knew a handful of queer poets of color and now my whole life is surrounded by your community. Thank you for making this journal possible! This year, we read thousands of poems to consider for publication in Nepantla. We have published twenty-seven poets below (three of them being posthumous publications). It's getting increasingly more difficult to publish all of the amazing poems we encounter during the submissions process. Please do not be discouraged from submitting to us multiple years! This decision, to publish posthumously, was made in a deep desire to carry the legacies of those who have helped shape our understandings of self and survival in the world. With Nepantla we want to honor those who have proceeded us and honor those who are currently living. We are proud to be publishing the voices of June Jordan, Akilah Oliver, and tatiana de la tierra in Issue #3. This year's issue was made possible by a grant from the organization 'A Blade of Grass.' Also, I want to acknowledge other queer of color journals that have formed in the recent years too. I believe that having a multitude of journals, and not a singular voice, for our community is extremely important. Oftentimes, people believe in a destructive competition which doesn't allow for their communities to flourish. -

Biographies of the Contributors Norma Alarcon Born in Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico and Raised in Chicago

246 Biographies of the Contributors Norma Alarcon Born in Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico and raised in Chicago. Will receive Ph.D. in Hispanic Literatures in 1981 from Indiana University where she is presently employed as Visiting Lecturer in Chicano- Riqueno Studies. Gloria Evangelina Anzaldtia I'm a Tejana Chicana poet, hija de Amalia, Hecate y Yemaya. I am a Libra (Virgo cusp) with VI – The Lovers destiny. One day I will walk through walls, grow wings and fly, but for now I want to play Hermit and write my novel, Andrea. In my spare time I teach, read the Tarot, and doodle in my journal. Barbara M. Cameron Lakota patriot, Hunkpapa, politically non-promiscuous, born with a caul. Will not forget Buffalo Manhattan Hat and Mani. Love Marti, Maxine, Leonie and my family. Still beading a belt for Pat. In love with Robin. Will someday raise chickens in New Mexico. Andrea R. Canaan Born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1950. Black woman, mother and daughter. Director of Women And Employment which develops and places women on non-traditional jobs. Therapist and counselor to bat- tered women, rape victims, and families in stress. Poetry is major writing expression. Speaker, reader, and community organizer. Black feminist writer. Jo Carrillo Died and born 6000 feet above the sea in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Have never left; will never leave. But for now, I'm living in San Fran- cisco. I'm loving and believing in the land, my extended family (which includes Angie, Mame and B. B. Yawn) and my sisters. Would never consider owning a souvenir chunk of uranium. -

SPR2013 SOC200 Syllabus DRAFT.Docx

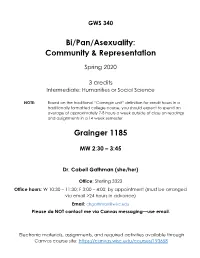

GWS 340 Bi/Pan/Asexuality: Community & Representation Spring 2020 3 credits Intermediate; Humanities or Social Science NOTE: Based on the traditional “Carnegie unit” definition for credit hours in a traditionally formatted college course, you should expect to spend an average of approximately 7-8 hours a week outside of class on readings and assignments in a 14-week semester Grainger 1185 MW 2:30 – 3:45 Dr. Cabell Gathman (she/her) Office: Sterling 3323 Office hours: W 10:30 – 11:30; F 3:00 – 4:00; by appointment (must be arranged via email >24 hours in advance) Email: [email protected] Please do NOT contact me via Canvas messaging—use email. Electronic materials, assignments, and required activities available through Canvas course site: https://canvas.wisc.edu/courses/193658 – 2 – Course Description Bisexual/biromantic, pansexual/panromantic, and asexual/aromantic (BPA) people are often denied (full) membership in the "queer community," or assumed to have the same experiences and concerns as lesbian and gay (LG) people and thus not offered targeted programs or services. Recent research has shown a wide variety of negative outcomes experienced by bisexual/biromantic people at much higher rates than LG people, and still barely acknowledges the existence of pansexual/panromantic or asexual/aromantic people. (Although research differentiating pan and bi people is still quite sparse, what exists suggests that systematic differences may exist between these groups, as well.) This course builds on concepts and information covered in Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies (GWS 200). It will explore the experiences, needs, and goals of BPA people, as well as their interactions with the mainstream lesbian & gay community and overlap and coalition building with other marginalized groups. -

June Jordan's Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler in Her Poetry, the Late African Am

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 38 (2013): 65-82 “I am she who will be free”: June Jordan’s Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler In her poetry, the late African American writer June Jordan (1936- 2002) approaches cultural disputes, violent conflicts, as well as transnational issues of equality and inclusion from an all-encompassing, global angle. Her rather singular way of connecting feminism, female sexual identity politics, and transnational issues from wars to foreign policy facilitates an investigation of the role of poetry in the context of Transnational Feminisms at large. The transnational quality of her literary oeuvre is not only evident thematically but also in her style and her use of specific poetic forms that encourage cross-cultural dialogue. By “mapping connections forged by different people struggling against complex oppressions” (Friedman 20), Jordan becomes part of a multicultural feminist discourse that takes into account the context-dependency of oppressions, while promoting relational ways of thinking about identity. Through forging links and loyalties among diverse groups without silencing the complexities and historical specificities of different situations, her writing inspires a “polyvocal” (Mann and Huffmann 87) feminism that moves beyond fixed categories of race, sex and nation and that works towards a more “relational” narration of conflicts and oppressions across the globe (Friedman 40). Jordan’s poetry consciously reflects upon the experience of being female, black, bisexual, and American. Thus, her work speaks from an angle that is at the same time dominant and marginal. To put it in her own words: “I am Black and I am female and I am a mother and I am a bisexual and I am a nationalist and I am an antinationalist. -

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms Mollie Blackburn Mary Catherine Miller Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Art Classrooms KEY TERMS Equity Assistance Centers (EACs) are charged with providing technical assistance, LGBTQ - The acronym used to represent lesbian, gay, including training, in the area of sex bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning identities and desegregation, among other areas of themes. We recognize that this acronym excludes some desegregation, of public elementary and people, like those who are asexual or intersex, but we aim to secondary schools. Sex desegregation, here, be honest about who gets featured in literature representing sexual and gender minorities. means the “assignment of students to public schools and within those schools without regard Gender - While “sex” is the biological differentiation of being to their sex including providing students with a male or female, gender is the social and cultural presentation full opportunity for participation in all of how an individual self-identifies as masculine, feminine, or within a rich spectrum of identities between the two. Gender educational programs regardless of their roles are socially constructed, and typically reinforced in a sex” (https://www.federalregister.gov/ gender binary that places masculine and feminine roles in documents/2016/03/24/2016-06439/equity- opposition to each other. assistance-centers-formerly-desegregation- Cisgender - An individual who identifies as the gender assistance-centers). This is pertinent to LGBTQ corresponding with the sex they were assigned at birth students. Most directly, students who identify as (Aultman, 2014; Stryker, 2009). By using cisgender to trans or gender queer are prevented from distinguish someone as not transgender, the term “helps attending school because of the transphobia distinguish diverse sex/gender identities without reproducing they experience there. -

Analyzing the Combahee River Collective As a Social Movement

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, The Trinity Papers (2011 - present) Catalogs, etc.) 2019 Analyzing the Combahee River Collective as a Social Movement Alexander Gnassi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/trinitypapers Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gnassi, Alexander, "Analyzing the Combahee River Collective as a Social Movement". The Trinity Papers (2011 - present) (2019). Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford, CT. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/trinitypapers/74 Analyzing the Combahee River Collective as a Social Movement Alexander Gnassi Sociological analysis of social movements has progressed dialectically, each new theory building off and in contrast to what previously existed, whilst what previously existed is modified as newer theories bring up relevant new ideas. Three theories—Collective Behavior Theory (CB), Resource Mobilization Theory (RMT), and Political Process Theory (PPT)—best illustrate this dialectical relationship through their many commonalities and clear departures from one another (Edwards 2017). Across the theories, four general elements of social movements are proffered: social movements are collective organized efforts at social change, they are durable over a period of time and engage with a powerful opponent on a conflictual issue, members of a social movement share a collective identity, and social movements utilize protest as a mechanism to achieve their goals (Edwards 2017). All three theories identify social problems as a necessary element, though not a causal factor, of collective action, protest, and social movements. In general, contemporary conceptualizations of social movements are moving toward “a ‘rational’ understanding of what social movements are and how they operate” (Edwards 2017:8). -

Novel Approaches to Negotiating Gender and Sexuality in the Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The olorC Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Selha, A. D., "Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The oC lor Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues" (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 9. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -r Distracting the border guards: Novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies Major Professor: Kathy Hickok Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1997 1 ii JJ Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of A.D. Selha has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University 1 1 11 iii DEDICATION For those who have come before me, I request your permission to write in your presence, to illuminate your lives, and draw connections between the communities which you may have painfully felt both a part of and apart from. -

Spring 1989 Newsletter

NewYorkCityWritingProJect NEWSLETTER Volumes, Number 2 Spring 1989 Tapping Wellsprings And Moving To Action It is Saturday, January 14. I am part of a two-day inquiry a variation of the "theme" idea that would aid teachers in various workshop. Twenty-two Writing Project teachers have come subject areas, and be great for social studies teachers. Every together at Lehman College over the weekend to be pan of a time I asked someone about inquiry, I got a response like the one workshop directed by Elaine Avidon and Gail Kleiner. I had I give when people ask me about the writing process: "You heard a lot about "inquiry." I thought it was a technique that have to experience it" would be useful for me as a teacher and as a teacher-consultant; So here I am in a classroom on this cold gray Saturday morning. We are given our topic: the impact of race on the success of minority students in urban schools. Tine," I think, Important Risks "It's a place to begin." We have only two days and I have not come with a specific agenda. I really just want to experience an How we teach, and, as a corollary to this, how we allow our students to learn, has a profound impact on the life-long stances inquiry for myself, and get a look at the various procedures one of our students. The roles students are continually permitted to can use. play contribute to the roles they take on in the larger world of ideas and institutions. We worry greatly about this, given the I am intellectually, if not emotionally, engaged by this topic. -

This Bridge Called My Back Writings by Radical Women of Color £‘2002 Chenic- L

This Bridge Called My Back writings by radical women of color £‘2002 Chenic- L. Moiaga and Gloria E. Anzaldua. All rights reserved. Expanded and Re vised Third Edition, First Pr nLing 2002 First Edition {'.'1981 Cherrie L. Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldua Second Edition C 1983 Cherne L. Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldua All rights reserved under International an d Pan American Copyright Conventions. Published by Third Woman Press. Manufactured in the United Stales o( America. Printed and b ound by M c Na ugh ton & Gunn, Saline, Ml No p art of this book may be reproduced by any me chani cal photographic, or electronic process, or in the form of a phonographic recording nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise copied, for public or private use, without tne prior written permission of the publisher. Address inquiries to: Third Woman Press. Rights and Permissions, 1329 9th Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 or www.thirdwomanpress.com Cover art: Ana Mendieta, Body Tracks (1974), perfomied bv the artist, blood on white fabric, University of Iowa. Courtesy of the Estate of Ana Mendieta and Galerie Lelong, NYC. Cover design: Robert Barkaloff, Coatli Design, www.coatli.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data This b ridge called my back : writ ines by radical women of color / edi tors, Cherne L. Moraga, Gloria E. AnzaTdua; foreword, Toni Cade Bambara. rev an d expanded 3rd ed. p.cm. (Women of Color Series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-943219-22-1 (alk. paper) I. Feminism-Literary collections. 2. Women-United States-Literary collections.