Bruckner Journal V6 2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward Elgar: the Dream of Gerontius Wednesday, 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall

EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS WEDNESDAY, 7 MARCH 2012 ROYAL FESTIVAL HALL PROGRAMME: £3 royal festival hall PURCELL ROOM IN THE QUEEN ELIZABETH HALL Welcome to Southbank Centre and we hope you enjoy your visit. We have a Duty Manager available at all times. If you have any queries please ask any member of staff for assistance. During the performance: • Please ensure that mobile phones, pagers, iPhones and alarms on digital watches are switched off. • Please try not to cough until the normal breaks in the music • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. • There will be a 20-minute interval between Parts One and Two Eating, drinking and shopping? Southbank Centre shops and restaurants include Riverside Terrace Café, Concrete at Hayward Gallery, YO! Sushi, Foyles, EAT, Giraffe, Strada, wagamama, Le Pain Quotidien, Las Iguanas, ping pong, Canteen, Caffè Vergnano 1882, Skylon and Feng Sushi, as well as our shops inside Royal Festival Hall, Hayward Gallery and on Festival Terrace. If you wish to contact us following your visit please contact: Head of Customer Relations Southbank Centre Belvedere Road London SE1 8XX or phone 020 7960 4250 or email [email protected] We look forward to seeing you again soon. Programme Notes by Nancy Goodchild Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie © London Concert Choir 2012 www.london-concert-choir.org.uk London Concert Choir – A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and with registered charity number 1057242. Wednesday 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS Mark Forkgen conductor London Concert Choir Canticum semi-chorus Southbank Sinfonia Adrian Thompson tenor Jennifer Johnston mezzo soprano Brindley Sherratt bass London Concert Choir is grateful to Mark and Liza Loveday for their generous sponsorship of tonight’s soloists. -

Principal Partner 2 an ORCHESTRA LIKE NO OTHER Meet Southbank Sinfonia: 33 Outstanding Young Players Poised to Make a Significant Impact on the Music Profession

Principal partner 2 AN ORCHESTRA LIKE NO OTHER Meet Southbank Sinfonia: 33 outstanding young players poised to make a significant impact on the music profession. Every year we welcome an entirely new cohort of exceptional talents from all over the world and are fascinated to hear and see what they will achieve together. Let them guide you through a vast array of repertoire and invigorating collaborations with artists such as Antonio Pappano, Vladimir Ashkenazy and Guy Barker as well as venerable organisations like the Royal Opera House and Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Whatever events you can attend, you are sure to experience the immense energy and freshness the players bring to every performance. They make a blazing case for why orchestras still matter today, investing new life in a noble tradition and reminding us all what can be accomplished when dedicated individuals put their hearts and minds together. Join us on their remarkable journey, and be enlivened and inspired. Simon Over Music Director and Principal Conductor For the latest concert listings and to book tickets online, visit us at southbanksinfonia.co.uk All information in this Concert Diary was correct at the time of going to press, but Southbank Sinfonia reserves the right to vary programmes if necessary. 3 MEET THE PLAYERS Alina Hiltunen Karla Norton Anaïs Ponty Duncan Anderson Violin Violin Violin Viola Yena Choi Tamara Elias Rachel Gorman Kaya Kuwabara Cara Laskaris Colm O’Reilly Timothy Rathbone Violin Violin Violin Violin Violin Violin Violin Martha Lloyd Helen -

London Concert Choir Counterpoint Mark Forkgen Conductor

HANDEL MESSIAH London Concert Choir Counterpoint Mark Forkgen Conductor Wednesday 14 December, 2011 Programme: £2 Cadogan Hall, 5 Sloane Terrace, London SW1X 9DQ Booking: 020 7730 4500 / www.cadoganhall.com WELCOME TO CADOGAN HALL In the interests of your comfort and safety, please note the following: • Latecomers will only be admitted to the auditorium during a suitable pause in the performance. • Cadogan Hall is a totally non-smoking building. • Glasses, bottles and food are not allowed in the auditorium. • Photography, and the use of any video or audio recording equipment, is forbidden. • Mobiles, Pagers & Watches: please ensure that you switch off your mobile phone and pager, and deactivate any digital alarm on your watch before the performance begins. • First Aid: Please ask a Steward if you require assistance. Thank you for your co-operation. We hope you enjoy the performance. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Programme notes ©2011 Nancy Goodchild Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie London Concert Choir - A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 HANDEL MESSIAH London Concert Choir Counterpoint Mark Forkgen Conductor Erica Eloff Soprano | Christopher Lowrey Counter tenor James Geer Tenor | Giles Underwood Bass-Baritone There will be an INTERVAL of 20 minutes after Part One Hope and support for troubled children through art and music…… In our experience, children and young people may not want to talk about what is troubling them. At Chance for Children we help those who have experienced traumatic situations, including bereavement, domestic violence, war or criminal activity in their families, to recover by expressing their feelings in a safe way. -

Rachmaninov Liturgy of St John Chrysostom London Concert Choir Conductor: Mark Forkgen

Tuesday 23 October 2012 St. Sepulchre’s Church, Holborn Viaduct, EC1 Rachmaninov Liturgy of St John Chrysostom London Concert Choir Conductor: Mark Forkgen Programme £2 Please note: • The consumption of food is not permitted in the church. • Please ensure that all mobile phones, pagers, and alarms on digital watches are switched off. • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. • There will be a 20-minute Interval, during which drinks will be served. Programme Notes © David Knowles Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie London Concert Choir A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 Registered Office 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU St Sepulchre-without-Newgate: The National Musicians’ Church This is the first time that London Concert Choir has performed at St Sepulchre’s. Named after the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the church is first mentioned in 1137. It was grandly re-built in 1450 only to be badly damaged in the Great Fire of 1666. The burnt-out shell was rebuilt by Wren’s masons in 1670-71. St Sepulchre’s now stands as the largest parish church in the City of London. Famous in folklore, the twelve ‘Bells of Old Bailey’ are remembered in the rhyme ‘Oranges and Lemons’. The great bell of St Sepulchre’s tolled as condemned men passed from Newgate prison towards the gallows. On midnight of an execution day, St Sepulchre’s Bellman would pass by an underground passage to Newgate Prison and ring twelve double tolls to the prisoner on the Execution Bell, whilst reciting a rhymed reminder that the day of execution had come. -

CLASS:Aktuell

2012/Nr.3 CLASS: aktuell Association of Classical Independents in Germany Martin Spangenberg mit Webers Klarinettenkonzerten Utrecht String Quartet Kammermusik von Carlos Micháns Meta4 und Minetti Quartett Gänsehautschönheit Christian Zacharias Fulminanter Schlusspunkt Frauke Hess Phantastischer Dialog Michala Petri Preisgekrönte Nachtigall Thomas Albertus Irnberger Echo Klassik 2012 Ein unruhiger Geist mit großem Gewinnspiel Sonntag, 14. Oktober 2012 Konzerthaus Berlin Die ECHO Klassik-Verleihung wird am 14. Oktober 2012 um 22 Uhr im ZDF ausgestrahlt. www.echoklassik.de | www.facebook.com/ECHO.Klassik EchoKlassik2012_Anzeige_Class.indd 1 28.08.2012 10:39:23 Uhr CLASS: aktuell CLASS: aktuell 3/2012 Inhalt Musik ist älter als der Mensch. Bevor unsere Ur-Ur-Vorfahren zu singen und zu 4 Ein unruhiger Geist musizieren begannen, hatte unsere Spezies nämlich unzählige Tausende von Jahren den Der Geiger Thomas Albertus Irnberger Vögeln zugehört. Im Gesang der Vögel steckt schon alles, was wir als Musik empfinden: 6 Schlemmen à la française Melodie, Rhythmus, Phrase, auch Improvisation, Duett und Mehrstimmigkeit. Weltweit mit dem Trio Parnassus erzählen Mythen und Legenden davon, dass die Menschen das Singen von den Vögeln 7 Debüt: Martin Spangenberg lernten. Auch den Buckelwalen haben manche Völker jahrtausendelang gelauscht. mit Webers Klarinettenkonzerten Die Lieder der Buckelwale besitzen Motive, Rhythmen und Form, dauern in der Regel fünf 8 Preisgekrönte Nachtigall bis 16 Minuten lang und benutzen den gleichen Tonumfang wie ein Konzertflügel. Michala Petri mit zeitgenössischen Entdeckungen Die Ur-Lust, das Eigentliche 9 Weltenbürger mit Doppelstrategie Kammermusik von Carlos Micháns mit dem Utrecht String Quartet Was Musik diesen Tieren bedeutet, wissen wir nicht. Doch ebenso wenig wissen wir, warum uns Menschen Musik so sehr ergreift, warum sie uns traurig oder fröhlich stimmt, 10 Gänsehautschönheit warum sie zu uns spricht, ohne etwas Bestimmtes zu sagen, und warum sie in unserem Meta4 und Minetti Quartett Gehirn dieselben Effekte hat wie eine Droge. -

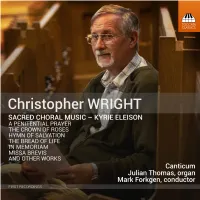

TOCC0457DIGIBKLT.Pdf

MY SACRED CHORAL MUSIC – KYRIE ELEISON by Christopher Wright A few words of introduction first, if you will allow me. I was born in 1954 and am a native of Suffolk, where I also live now. My earliest compositions, composed when I was still at school, were Four Short Piano Preludes and a quartet, Kyson Point (named after a local Woodbridge beauty spot), scored for flute, oboe, violin and cello and premiered at an East Anglian New Music Society concert in Ipswich in 1971 – my first public performance. On leaving school, I went on to study music at The Colchester Institute, where I received composition lessons from Richard Arnell. After graduating, I took up various teaching posts in class music, as a peripatetic brass teacher, in both state and independent establishments. I also studied composition with Stanley Glasser at Goldsmiths College (part of London University) and with Nicholas Sackman at Nottingham University. During my years as a schoolteacher, little time was available for composing and only a handful of works materialised, among them Patterns for brass band (1978), String Quartet No. 1 (1980), Armageddon for large orchestra and tape (1980) and a brass quintet subtitled Music for Youth (1977). My first commission came in 1985 from the Cheltenham International Violin Course – my Concertino for Violin Orchestra and Piano. When I left teaching in 1993, the invaluable asset of time gave me space to think, compose and organise performances. The first piece to emerge, in 1994, was a wind quintet with the subtitle ‘...the ceremony of innocence is drowned’ (a line from W. -

Piano News (Issue of February 2007) Choose the CD 1567 As CD of the Month

Fumiko Shiraga was born in Tokyo to musically educated parents. She started playing the piano at the age of three and moved to Germany at the age of six. She was a student of Professor Detlef Kraus, Friedrich Wilhelm Schnurr and Vladimir Krainev. In 1995 she completed her studies in Hanover, achieving the highest distinction in her soloist examinations. Parallel to her final years of studies she was intensively taken care of by the Polish teacher Malgorzata Bator-Schreiber. Fumiko Shiraga has won numerous prizes in national and international competitions. Fumiko Shiraga received much inspiration of artistic value by attending international master classes held by Nikita Magaloff, Yara Bernette, Jeremy Menuhin, Paul Badura-Skoda, Edith Picht-Axenfeld and John O´Conor (Fondazione Wilhelm Kempff/Positano). Fumiko Shiraga played solo evenings, orchestra concerts and chamber music concerts in London, Budapest, Salzburg, Gstaad, Helsinki, Riga, Kiev, Istanbul, Beirut, San José, at the Schleswig Holstein Music Festival, at the Bremen Music Festival, the Mozart Festival Wuerzburg, the Rheingau Music Festival and the renowned Chopin Festival in Duszniki/Polen. She also gave concerts in the Herkulessaal in Munich, the Laeiszhalle in Hamburg, the Bruckner House Linz, the Casals Hall Tokyo and the great hall of the Tschaikowsky Conservatory in Moskow. Amongst innumerable concerts in Germany she regularly played concerts for the recording of miscellaneous radio stations, such as NDR (Norddeutscher Rundfunk = northern Germany radio station), BR (Bayerischer Rundfunk = Bavarian radio station), SWR (Südwestrundfunk, south-west Germany radio station), HR (Hessischer Rundfunk = Hesse radio). Ever since 1996 she has played various concertos for the Swedish label BIS, where she caused furore worldwide with the series ”Piano concertos in disguise“. -

Kammermusik Auf Haus Opherdicke

klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll musikalisch hören musikalisch hören sehen klangvoll hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen klang sievoll klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll gefühlvoll musik fühlvoll musikalisch klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll musikalisch hören klangvoll phantasievoll hören musikalisch hören sehen phan klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasie sehen klangvoll hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen klangvoll musik sievoll klangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll gefühlvoll musikalisch hören gefühlvollKammermusik musikalisch klangvoll auf musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll musikalisch hörenHaus sehen phantasievoll Opherdicke musikalisch hören klangvoll phantasievoll hören musikalisch2015 hören sehen phanklangvoll musikalisch hören sehen phantasievoll klangvoll gefühlvoll musik phantasievoll Programmübersicht Donnerstag | 29.01.2015 | 20.00 Uhr Fumiko Shiraga (Klavier) und David Stromberg (Violoncello) Donnerstag | 26.02.2015 | 20.00 Uhr Balletto Terzo – Trio für Alte Musik Sigrun Stephan (Cembalo, Harfe) | Brigitta Borchers (Gesang) Andreas Nachtsheim (Laute, Chitarrone, Barockgitarre) Donnerstag | 19.03.2015 | 20.00 Uhr Ensemble Correlatif – Das Holzbläserquartett Christian Strube (Flöte) | Marion Klotz (Oboe) | Matthias Beltz (Klarinette) | Anne Weber-Krüger (Fagott) Donnerstag | 30.04.2015 -

Recent Publications in Music 2012

1 of 149 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2012 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove and David Sommerfield This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2011. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in conjuction with Fontes artis musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compilers welcome inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS. Argentina: Estela Escalada Japan: SEKINE Toshiko Australia: Julia Mitford Kenya: Santie De Jongh Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Malawi: Santie De Jongh Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Mexico: Daniel Villanueva Rivas, María Del China: Katie Lai Consuelo García Martínez Croatia: Žeiljka Radovinović The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert Denmark: Anne Ørbæk Jensen New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Estonia: Katre Rissalu Nigeria: Santie De Jongh Finland: Tuomas Tyyri Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina France: Élisabeth Missaoui Serbia: Radmila Milinković Germany: Susanne Hein South Africa: Santie De Jongh Ghana: Santie De Jongh Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis González Ribot Greenland: Anne Ørbæk Jensen Taiwan: Katie Lai Hong Kong: Katie Lai Turkey: Senem Acar, Paul Alister Whitehead Hungary: SZEPESI Zsuzsanna Uganda: Santie De Jongh Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Ireland: Roy Stanley United States: Karen Little, Lindsay Hansen Italy: Federica Biancheri Uruguay: Estela Escalada With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Ana Cristán, Paul Frank, Irina Kirchik, Everette Larson, Miroslava Nezar, Joan Weeks, and Thompson A. -

Download Concert Programme

Th ursday 7 November 2019, 7.30pm Cadogan Hall, Sloane Terrace, SW1 Celebrating 60 years PURCELL KING ARTHUR CONCERT PERFORMANCE Programme £3 Welcome to Cadogan Hall Please note: • Latecomers will only be admitted to the auditorium during a suitable pause in the performance. • All areas of Cadogan Hall are non-smoking areas. • Glasses, bottles and food are not allowed in the auditorium. • Photography, and the use of any video or audio recording equipment, is forbidden. PURCELL • Mobiles, Pagers & Watches: please ensure that you switch off your mobile phone and pager, and deactivate any digital alarm on your watch before the performance begins. • First Aid: Please ask a Steward if you require assistance. • Thank you for your co-operation. We hope you enjoy the concert. Programme notes adapted from those by Michael Greenhalgh, facebook.com/ by permission of Harmonia Mundi. londonconcertchoir Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie instagram.com/ London Concert Choir is a company limited by guarantee, londonconcertchoir incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 @ChoirLCC Registered Office: 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU Thursday 7 November 2019 Cadogan Hall PURCELL KING ARTHUR CONCERT PERFORMANCE Mark Forkgen conductor Rachel Elliott soprano Rebecca Outram soprano Bethany Partridge soprano William Towers counter tenor James Way tenor Peter Willcock bass baritone Aisling Turner and Joe Pike narrators London Concert Choir Counterpoint Ensemble There will be an interval of 20 minutes after ACT III Henry Purcell (1659–1695) King Arthur Semi-opera in five acts Libretto by John Dryden The first concert in the choir’s 60th Anniversary season is Purcell’s dramatic masterpiece about the conflict between King Arthur’s Britons and the heathen Saxon invaders. -

Seasons in the Basilica at Assisi Active Involvement

Supporting the Choir London Concert Choir is one of London’s leading amateur choirs. A lively and friendly choir with around 150 members London Concert Choir is committed to high and an unusually broad repertoire, LCC regularly appears standards and constantly strives to raise the level of at all the major London concert venues as well as visiting its performances by means of workshops and other special events. The choir is grateful for the financial destinations further afield. In 2014 the choir performed contribution of its supporters and welcomes their Haydn’s oratorio The Seasons in the Basilica at Assisi active involvement. with Southbank Sinfonia. A tour to Poland will take place in July 2016. For information on how you can help the choir to achieve its aims, please contact: LCC celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2010 with two [email protected] memorable performances of Britten’s War Requiem – at the Conductor: Mark Forkgen Barbican and in Salisbury Cathedral. In 2011 a performance Enquiries about opportunities for sponsorship and of Verdi’s Requiem with the Augsburg Basilica Choir in programme advertising should be sent to the same address. the Royal Festival Hall was followed by a joint concert at the Augsburg Peace Festival. Other major works in earlier Joining the Choir seasons include Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis with the English Chamber Orchestra, and Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and The choir welcomes new members, who are invited to Mendelssohn’s Elijah with Southbank Sinfonia. attend a few rehearsals before an informal audition. If you are interested, please fill in your details online at: Performances of Baroque music with Counterpoint include Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus and Bach’s St Matthew Passion. -

Swr2 Programm Kw 20

SWR2 PROGRAMM - Seite 1 - KW 20 / 17. - 23.05.2021 Ferenc Farkas: Diese haben auch Komponistinnen und Montag, 17. Mai Alte ungarische Tänze aus Komponisten in vielfältiger Weise inspi- dem 17. Jahrhundert riert – von den Epen des Mittelalters bis 0.03 ARD-Nachtkonzert István-Zsolt Nagy (Flöte) zur Opernbühne der Moderne. Die Richard Strauss: Budapest Strings SWR2 Musikstunde folgt den Spuren, Hornkonzert Nr. 1 Es-Dur op. 11 Giuseppe Ferlendis: die Heroinen und Heroen in der Musik Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden Oboenkonzert Nr. 1 F-Dur hinterlassen haben. Leitung: Christian Thielemann Heinz Holliger (Oboe) Georg Friedrich Händel: Academy of St. Martin in the Fields 10.00 Nachrichten, Wetter Suite g-Moll HWV 432 Leitung: Kenneth Sillito Ragna Schirmer (Klavier) Benedetto Marcello: 10.05 SWR2 Treffpunkt Klassik Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Konzert e-Moll op. 1 Nr. 2 Musik. Meinung. Perspektiven. Violinkonzert e-Moll op. 64 Sonatori de la Gioiosa Marca Alina Pogostkina (Violine) Gaetano Donizetti: 11.57 SWR2 Kulturservice MDR-Sinfonieorchester Sonate F-Dur Leitung: Mario Venzago Larissa Kondratjewa, 12.00 Nachrichten, Wetter Ernst von Dohnányi: Reinhard Schmiedel (Klavier) Serenade C-Dur op. 10 Luka Sorkocevic: 12.05 SWR2 Aktuell Abigél Králik (Violine) Sinfonie Nr. 2 G-Dur Ulrich Eichenauer (Viola) Salzburger Hofmusik 12.30 Nachrichten Andreas Brantelid (Violoncello) Leitung: Wolfgang Brunner Joseph Haydn: 12.33 SWR2 Journal am Mittag Oboenkonzert C-Dur Hob. VIIg/C1 6.00 SWR2 am Morgen Das Magazin für Kultur und Gesellschaft Pierre Pierlot (Oboe) darin bis 8.30 Uhr: Franz Liszt Kammerorchester u. a. Pressestimmen, 12.59 SWR2 Programmtipps Leitung: János Rolla Kulturmedienschau und Kulturgespräch 13.00 Nachrichten, Wetter 2.00 Nachrichten, Wetter 6.00 SWR2 Aktuell 13.05 SWR2 Mittagskonzert 2.03 ARD-Nachtkonzert 6.20 SWR2 Zeitwort Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Camille Saint-Saëns: 17.05.1874: Die Strandungs- des SWR Violoncellokonzert Nr.