London Concert Choir Counterpoint Mark Forkgen Conductor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward Elgar: the Dream of Gerontius Wednesday, 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall

EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS WEDNESDAY, 7 MARCH 2012 ROYAL FESTIVAL HALL PROGRAMME: £3 royal festival hall PURCELL ROOM IN THE QUEEN ELIZABETH HALL Welcome to Southbank Centre and we hope you enjoy your visit. We have a Duty Manager available at all times. If you have any queries please ask any member of staff for assistance. During the performance: • Please ensure that mobile phones, pagers, iPhones and alarms on digital watches are switched off. • Please try not to cough until the normal breaks in the music • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. • There will be a 20-minute interval between Parts One and Two Eating, drinking and shopping? Southbank Centre shops and restaurants include Riverside Terrace Café, Concrete at Hayward Gallery, YO! Sushi, Foyles, EAT, Giraffe, Strada, wagamama, Le Pain Quotidien, Las Iguanas, ping pong, Canteen, Caffè Vergnano 1882, Skylon and Feng Sushi, as well as our shops inside Royal Festival Hall, Hayward Gallery and on Festival Terrace. If you wish to contact us following your visit please contact: Head of Customer Relations Southbank Centre Belvedere Road London SE1 8XX or phone 020 7960 4250 or email [email protected] We look forward to seeing you again soon. Programme Notes by Nancy Goodchild Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie © London Concert Choir 2012 www.london-concert-choir.org.uk London Concert Choir – A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and with registered charity number 1057242. Wednesday 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS Mark Forkgen conductor London Concert Choir Canticum semi-chorus Southbank Sinfonia Adrian Thompson tenor Jennifer Johnston mezzo soprano Brindley Sherratt bass London Concert Choir is grateful to Mark and Liza Loveday for their generous sponsorship of tonight’s soloists. -

Principal Partner 2 an ORCHESTRA LIKE NO OTHER Meet Southbank Sinfonia: 33 Outstanding Young Players Poised to Make a Significant Impact on the Music Profession

Principal partner 2 AN ORCHESTRA LIKE NO OTHER Meet Southbank Sinfonia: 33 outstanding young players poised to make a significant impact on the music profession. Every year we welcome an entirely new cohort of exceptional talents from all over the world and are fascinated to hear and see what they will achieve together. Let them guide you through a vast array of repertoire and invigorating collaborations with artists such as Antonio Pappano, Vladimir Ashkenazy and Guy Barker as well as venerable organisations like the Royal Opera House and Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Whatever events you can attend, you are sure to experience the immense energy and freshness the players bring to every performance. They make a blazing case for why orchestras still matter today, investing new life in a noble tradition and reminding us all what can be accomplished when dedicated individuals put their hearts and minds together. Join us on their remarkable journey, and be enlivened and inspired. Simon Over Music Director and Principal Conductor For the latest concert listings and to book tickets online, visit us at southbanksinfonia.co.uk All information in this Concert Diary was correct at the time of going to press, but Southbank Sinfonia reserves the right to vary programmes if necessary. 3 MEET THE PLAYERS Alina Hiltunen Karla Norton Anaïs Ponty Duncan Anderson Violin Violin Violin Viola Yena Choi Tamara Elias Rachel Gorman Kaya Kuwabara Cara Laskaris Colm O’Reilly Timothy Rathbone Violin Violin Violin Violin Violin Violin Violin Martha Lloyd Helen -

Rachmaninov Liturgy of St John Chrysostom London Concert Choir Conductor: Mark Forkgen

Tuesday 23 October 2012 St. Sepulchre’s Church, Holborn Viaduct, EC1 Rachmaninov Liturgy of St John Chrysostom London Concert Choir Conductor: Mark Forkgen Programme £2 Please note: • The consumption of food is not permitted in the church. • Please ensure that all mobile phones, pagers, and alarms on digital watches are switched off. • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. • There will be a 20-minute Interval, during which drinks will be served. Programme Notes © David Knowles Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie London Concert Choir A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 Registered Office 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU St Sepulchre-without-Newgate: The National Musicians’ Church This is the first time that London Concert Choir has performed at St Sepulchre’s. Named after the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the church is first mentioned in 1137. It was grandly re-built in 1450 only to be badly damaged in the Great Fire of 1666. The burnt-out shell was rebuilt by Wren’s masons in 1670-71. St Sepulchre’s now stands as the largest parish church in the City of London. Famous in folklore, the twelve ‘Bells of Old Bailey’ are remembered in the rhyme ‘Oranges and Lemons’. The great bell of St Sepulchre’s tolled as condemned men passed from Newgate prison towards the gallows. On midnight of an execution day, St Sepulchre’s Bellman would pass by an underground passage to Newgate Prison and ring twelve double tolls to the prisoner on the Execution Bell, whilst reciting a rhymed reminder that the day of execution had come. -

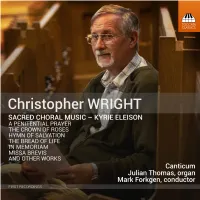

TOCC0457DIGIBKLT.Pdf

MY SACRED CHORAL MUSIC – KYRIE ELEISON by Christopher Wright A few words of introduction first, if you will allow me. I was born in 1954 and am a native of Suffolk, where I also live now. My earliest compositions, composed when I was still at school, were Four Short Piano Preludes and a quartet, Kyson Point (named after a local Woodbridge beauty spot), scored for flute, oboe, violin and cello and premiered at an East Anglian New Music Society concert in Ipswich in 1971 – my first public performance. On leaving school, I went on to study music at The Colchester Institute, where I received composition lessons from Richard Arnell. After graduating, I took up various teaching posts in class music, as a peripatetic brass teacher, in both state and independent establishments. I also studied composition with Stanley Glasser at Goldsmiths College (part of London University) and with Nicholas Sackman at Nottingham University. During my years as a schoolteacher, little time was available for composing and only a handful of works materialised, among them Patterns for brass band (1978), String Quartet No. 1 (1980), Armageddon for large orchestra and tape (1980) and a brass quintet subtitled Music for Youth (1977). My first commission came in 1985 from the Cheltenham International Violin Course – my Concertino for Violin Orchestra and Piano. When I left teaching in 1993, the invaluable asset of time gave me space to think, compose and organise performances. The first piece to emerge, in 1994, was a wind quintet with the subtitle ‘...the ceremony of innocence is drowned’ (a line from W. -

Recent Publications in Music 2012

1 of 149 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2012 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove and David Sommerfield This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2011. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in conjuction with Fontes artis musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compilers welcome inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS. Argentina: Estela Escalada Japan: SEKINE Toshiko Australia: Julia Mitford Kenya: Santie De Jongh Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Malawi: Santie De Jongh Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Mexico: Daniel Villanueva Rivas, María Del China: Katie Lai Consuelo García Martínez Croatia: Žeiljka Radovinović The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert Denmark: Anne Ørbæk Jensen New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Estonia: Katre Rissalu Nigeria: Santie De Jongh Finland: Tuomas Tyyri Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina France: Élisabeth Missaoui Serbia: Radmila Milinković Germany: Susanne Hein South Africa: Santie De Jongh Ghana: Santie De Jongh Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis González Ribot Greenland: Anne Ørbæk Jensen Taiwan: Katie Lai Hong Kong: Katie Lai Turkey: Senem Acar, Paul Alister Whitehead Hungary: SZEPESI Zsuzsanna Uganda: Santie De Jongh Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Ireland: Roy Stanley United States: Karen Little, Lindsay Hansen Italy: Federica Biancheri Uruguay: Estela Escalada With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Ana Cristán, Paul Frank, Irina Kirchik, Everette Larson, Miroslava Nezar, Joan Weeks, and Thompson A. -

Download Concert Programme

Th ursday 7 November 2019, 7.30pm Cadogan Hall, Sloane Terrace, SW1 Celebrating 60 years PURCELL KING ARTHUR CONCERT PERFORMANCE Programme £3 Welcome to Cadogan Hall Please note: • Latecomers will only be admitted to the auditorium during a suitable pause in the performance. • All areas of Cadogan Hall are non-smoking areas. • Glasses, bottles and food are not allowed in the auditorium. • Photography, and the use of any video or audio recording equipment, is forbidden. PURCELL • Mobiles, Pagers & Watches: please ensure that you switch off your mobile phone and pager, and deactivate any digital alarm on your watch before the performance begins. • First Aid: Please ask a Steward if you require assistance. • Thank you for your co-operation. We hope you enjoy the concert. Programme notes adapted from those by Michael Greenhalgh, facebook.com/ by permission of Harmonia Mundi. londonconcertchoir Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie instagram.com/ London Concert Choir is a company limited by guarantee, londonconcertchoir incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 @ChoirLCC Registered Office: 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU Thursday 7 November 2019 Cadogan Hall PURCELL KING ARTHUR CONCERT PERFORMANCE Mark Forkgen conductor Rachel Elliott soprano Rebecca Outram soprano Bethany Partridge soprano William Towers counter tenor James Way tenor Peter Willcock bass baritone Aisling Turner and Joe Pike narrators London Concert Choir Counterpoint Ensemble There will be an interval of 20 minutes after ACT III Henry Purcell (1659–1695) King Arthur Semi-opera in five acts Libretto by John Dryden The first concert in the choir’s 60th Anniversary season is Purcell’s dramatic masterpiece about the conflict between King Arthur’s Britons and the heathen Saxon invaders. -

Seasons in the Basilica at Assisi Active Involvement

Supporting the Choir London Concert Choir is one of London’s leading amateur choirs. A lively and friendly choir with around 150 members London Concert Choir is committed to high and an unusually broad repertoire, LCC regularly appears standards and constantly strives to raise the level of at all the major London concert venues as well as visiting its performances by means of workshops and other special events. The choir is grateful for the financial destinations further afield. In 2014 the choir performed contribution of its supporters and welcomes their Haydn’s oratorio The Seasons in the Basilica at Assisi active involvement. with Southbank Sinfonia. A tour to Poland will take place in July 2016. For information on how you can help the choir to achieve its aims, please contact: LCC celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2010 with two [email protected] memorable performances of Britten’s War Requiem – at the Conductor: Mark Forkgen Barbican and in Salisbury Cathedral. In 2011 a performance Enquiries about opportunities for sponsorship and of Verdi’s Requiem with the Augsburg Basilica Choir in programme advertising should be sent to the same address. the Royal Festival Hall was followed by a joint concert at the Augsburg Peace Festival. Other major works in earlier Joining the Choir seasons include Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis with the English Chamber Orchestra, and Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and The choir welcomes new members, who are invited to Mendelssohn’s Elijah with Southbank Sinfonia. attend a few rehearsals before an informal audition. If you are interested, please fill in your details online at: Performances of Baroque music with Counterpoint include Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus and Bach’s St Matthew Passion. -

Judas Maccabaeus

Thursday 6 November, 2014 Handel JUDAS MACCABAEUS Conductor: Mark Forkgen London Concert Choir Counterpoint Programme: £2 Cadogan Hall, 5 Sloane Terrace London SW1X 9DQ WELCOME TO CADOGAN HALL In the interests of your comfort and safety, please note the following: • Latecomers will only be admitted to the auditorium during a suitable pause in the performance. • Cadogan Hall is a totally non-smoking building. • Glasses, bottles and food are not allowed in the auditorium. • Photography, and the use of any video or audio recording equipment, is forbidden. • Mobiles, Pagers & Watches: please ensure that you switch off your mobile phone and pager, and deactivate any digital alarm on your watch before the performance begins. • First Aid: Please ask a Steward if you require assistance. Thank you for your co-operation. We hope you enjoy the performance. ______________________________________________________________________________________ Judas Maccabeus Words by Rev. Thomas Morell Music by George Frederic Handel Edited by Merlin Channon © Copyright Novello & Company Limited All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured. Used by permission of Novello & Company Limited. Programme note © Frances Cave 2014 Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie London Concert Choir - A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 Registered Office 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU Thursday 6 November, 2014 Cadogan Hall Handel: JUDAS MACCABAEUS -

Download Concert Programme

Wednesday 29 March 2017 RACHMANINOV THE BELLS Borodin: Polovtsian Dances Tchaikovsky: Polonaise from Eugene Onegin Fantasy Overture - Romeo and Juliet PROGRAMME: £3 Welcome to the Barbican In the interests of your comfort and safety, please note the following: • Please try to restrain coughing until the normal breaks in the performance. • If you have a mobile phone or digital watch, please ensure that it is turned off during the performance. • In accordance with the requirements of the licensing authority, sitting or standing in any gangway is not permitted. • No cameras, tape recorders, other types of recording apparatus, food or drink may be brought into the auditorium • It is illegal to record any performance unless prior arrangements have been made with the Managing Director and the concert promoter concerned. • Smoking is not permitted anywhere on Barbican premises. Barbican Centre, Silk St, London EC2Y 8DS Administration: 020 7638 4141 Box Office Telephone bookings: 020 7638 8891 (9am - 8pm daily: booking fee) www.barbican.org.uk (reduced booking fee online) Programme notes © David Nice Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie London Concert Choir - A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 Registered Office7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU Wednesday 29 March 2017, Barbican Hall Tchaikovsky: Polonaise from Eugene Onegin Borodin: Polovtsian Dances Tchaikovsky: Fantasy Overture - Romeo and Juliet INTERVAL RACHMANINOV: THE BELLS Mark Forkgen conductor London Concert Choir Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Natalya Romaniw soprano Andrew Rees tenor Michael Druiett bass baritone Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) Polonaise from Eugene Onegin If Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837) very soon came to be known as the ‘father of Russian literature’, he is also the father of Russian opera. -

Mass in Time of War Dona Nobis Pacem

Tuesday 27 September, 2011 Queen Elizabeth Hall WA R & PEACE HAYDN: MASS IN TIME OF WAR VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: DONA NOBIS PACEM Programme £2 royal festival hall PURCELL ROOM IN THE QUEEN ELIZABETH HALL Welcome to Southbank Centre and we hope you enjoy your visit. We have a Duty Manager available at all times. If you have any queries please ask any member of staff for assistance. During the performance: • Please ensure that mobile phones, pagers, iPhones and alarms on digital watches are switched off. • Please try not to cough until the normal breaks in the music • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. Eating, drinking and shopping? Southbank Centre shops and restaurants include Riverside Terrace Café, Concrete at Hayward Gallery, YO! Sushi, Foyles, EAT, Giraffe, Strada, wagamama, Le Pain Quotidien, Las Iguanas, ping pong, Canteen, Caffè Vergnano 1882, Skylon and Feng Sushi, as well as our shops inside Royal Festival Hall, Hayward Gallery and on Festival Terrace. If you wish to contact us following your visit please contact: Head of Customer Relations Southbank Centre Belvedere Road London SE1 8XX or phone 020 7960 4250 or email [email protected] We look forward to seeing you again soon. Programme Notes © Terry Barfoot Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie © London Concert Choir 2011 London Concert Choir - A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and with registered charity number 1057242. Tuesday 27 September 2011 Queen Elizabeth Hall, Southbank Centre WAR & PEACE HAYDN: MASS IN TIME OF WAR VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: DONA NOBIS PACEM Mark Forkgen conductor London Concert Choir City of London Sinfonia Helen Meyerhoff soprano Jeanette Ager mezzo soprano Nathan Vale tenor Colin Campbell baritone JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) Missa in tempore belli (Mass in Time of War) for soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor and bass soloists, chorus & orchestra 1. -

Raf Centenary Concert 100 Years of British Music

RAF CENTENARY CONCERT 100 YEARS OF BRITISH MUSIC Monday 11 June 2018 Programme: £3 Welcome to the Barbican In the interests of your comfort and safety, please note the following: • Please try to restrain coughing until the normal breaks in the performance. • If you have a mobile phone or digital watch, please ensure that it is turned off during the performance. • In accordance with the requirements of the licensing authority, sitting or standing in any gangway is not permitted. • No cameras, tape recorders, other types of recording apparatus, food or drink may be brought into the auditorium. • It is illegal to record any performance unless prior arrangements have been made with the Managing Director and the concert promoter concerned. • Smoking is not permitted anywhere on Barbican premises. Barbican Centre, Silk St, London EC2Y 8DS Administration: 020 7638 4141 Box Office Telephone bookings: 020 7638 8891 (9am - 8pm daily: booking fee) www.barbican.org.uk (reduced booking fee online) facebook.com/ Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie londonconcertchoir London Concert Choir is a company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 instagram.com/ and registered charity number 1057242 londonconcertchoir Registered Office: 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU @ChoirLCC londonconcertchoir.org Monday 11 June 2018 Barbican Hall RAF CENTENARY CONCERT 100 YEARS OF BRITISH MUSIC including the World Premiere of PER ARDUA AD ASTRA Through Adversity to the Stars by Roderick Williams -

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018 Holy Trinity Sloane Square in aid of Welcome to Holy Trinity Please note: • The consumption of food is not allowed in the Church. • Please switch off mobile phones and alarms on digital watches. • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. • There will be an interval of 20 minutes during which drinks will be served. LCC would like to thank the Volunteers from The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity and friends of the choir for their help with front-of-house duties. Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie Programme notes by Frances Cave and Eleanor Cowie, with acknowledgements to Making Music facebook.com/ London Concert Choir is a company limited by guarantee, londonconcertchoir incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 instagram.com/ Registered Office: londonconcertchoir 7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU @ChoirLCC www.londonconcertchoir.org BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Missa Brevis Chichester Psalms Interval Warm-Up, Three Songs Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Mark Forkgen conductor Nathan Mercieca countertenor Richard Pearce organ/piano Anneke Hodnett harp Sacha Johnson percussion The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity raises money solely to support The Royal Marsden, a world-leading cancer centre. We’re making a vital difference to the lives of cancer patients Life-saving Modern Patient research Environments By funding new clinical trials we can Patients need welcoming, dignified rapidly translate new discoveries into and peaceful environments that better treatments. enhance their wellbeing and support their recovery.