University of Huddersfield Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partial Listing of Gluten-Free “Mainstream” Products Available in the Chicago Area Or Through the Internet

PARTIAL LISTING OF GLUTEN-FREE “MAINSTREAM” PRODUCTS AVAILABLE IN THE CHICAGO AREA OR THROUGH THE INTERNET Updated March 5, 2005 Wheaton Gluten-Free Support Group This list was compiled from lists and postings on celiac and autism organizations’ websites and from information provided by manufacturers and retailers. In addition to products in this list, a wide variety of gluten-free specialty products are available, clearly labeled “gluten free.” This list is based on available information and does not claim to be complete. Its accuracy depends on the accuracy of the information provided by the product manufacturers. Information verification dates are given in parentheses. INGREDIENTS OF SOME PRODUCTS CHANGE OFTEN. FOR CURRENT INFORMATION, CHECK THE INGREDIENT LIST ON THE PRODUCT LABEL. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Shelf-Stable Entrees/Travel Foods .................................................................39 MIXES ........................................................................................................40 PICKLES AND OLIVES ................................................................................41 BAKERY/BREAD/TACOS/TORTILLAS.......................................................... 3 SALAD DRESSINGS ....................................................................................42 Waffles....................................................................................................... 3 SAUCES/CONDIMENTS ..............................................................................43 BAKING PRODUCTS ................................................................................... -

Mars Petcare Opens First Innovation Center in The

Contacts: Gregory Creasey (615) 807-4239 [email protected] MARS PETCARE OPENS FIRST INNOVATION CENTER IN THE UNITED STATES New $110 Million Gold LEED-Certified Campus Will Serve As Global Center of Excellence for Dry Cat and Dog Food THOMPSON’S STATION, TENN. (October 1, 2014) – Today Mars Petcare officially opened the doors of its new, state-of-the-art, Gold-LEED certified $110 million Global Innovation Center in Thompson’s Station, Tenn. The new campus, designed to help the company Make a Better World for Pets™ through pet food innovations, is the third Mars Petcare innovation center and first in the United States. It will serve as the global center of excellence for the company’s portfolio, which includes five billion dollar brands: PEDIGREE®, WHISKAS®, ROYAL CANIN®, BANFIELD® and IAMS®. The new center joins forces with similar Mars Petcare Global Innovation Centers located in Verden, Germany and Aimargues, France, and will focus on dry cat and dog food in both the natural and mainstream pet food categories. “Everything about this campus is dedicated to helping pets live longer and happier lives,” said Larry Allgaier, president of Mars Petcare North America. “Mars has been doing business in Tennessee for the past 35 years, employing nearly 1,700 Associates across our Petcare, Chocolate and Wrigley business segments. Our $110 million Global Innovation Center marks the sixth Mars site in Tennessee and will employ more than 140 Associates.” The location in Thompson’s Station was selected in part because of a great working relationship with the state of Tennessee, which is already home to Mars facilities in Cleveland, Chattanooga, Lebanon and Franklin (two locations). -

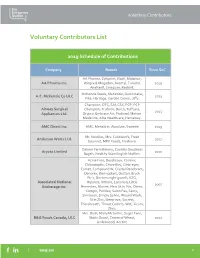

Voluntary Contributors List

Voluntary Contributors Voluntary Contributors List 2019 Schedule of Contributions Company Brands Since SoC AA Pharma, Zyloprim, Elavil, Midamor, AA Pharma Inc. Winpred, Mogadon, Aventyl, Toradol, 2019 Anafranil, Sinequan, Restoril. McKenzie Seeds, McKenzie, Gusto Italia, A.E. McKenzie Co ULC 2013 Pike, Heritage, Garden Corner, Jiffy. Champion, OTC, SAI, CSX, PCP, PCP Airway Surgical Champion, Truform, Darco, Tuffcare, 2013 Appliances Ltd. Drypro, Embrace Air, Proband, Motion Medecine, Alba Healthcare, Hemaway. AMC Direct Inc. AMC, Mehadrin, Absolute, Sweetie 2019 Mr. Noodles, Mrs. Cubbison’s, Fresh Anderson Watts Ltd. 2017 Gourmet, MPK Foods, Freshana. Oakrun Farm Bakery, Country Goodness Aryzta Limited 2010 Bagels, Healthy Start English Muffins. Acme Free, Boudreaux, Carmex, Chloraseptic, Chore Boy, Clear eyes, Comet, Compound W, Crystal Deodorant, Denorex, Dermoplast, Doctors Brush Pic's, Doctors night guards, EZO, Associated National Hylands, Inttimo, Lansinon, Little 2007 Brokerage Inc. Remedies, Murine, New Skin, Nix, Osteo, Outgro, Peridex, Salon Pas, Samy, Similasan, Simply Saline, Wound Wash, Skin Zinc, Sleep-eze, Sucrets, Therabreath, Throat Coolers, Wet, Zicam, Zims. Mrs. Dash, Molly Mcbutter, Sugar Twin, B&G Foods Canada, ULC Static Guard, Cream of Wheat, 2012 Underwood, Accent. 1 Voluntary Contributors Company Brands Since SoC Bellisio Food Canada Joy of Cooking, Michelina's. 2010 Bissell Canada Bissel. 2005 Corporation Blistex Inc. Blistex. 2015 Boshart Industries Inc. Iron Out, Plumbeeze Line. 2005 Bulk Barn Foods Ltd. Bulk Barn Foods. 2009 PediFix, Xenna, Silk Feet, Magni Life, Support Plus, Thera Sock, Thera Glove, Nova, No Rince, ArmRx, Hartmobility, Sea Band, Trion Z, Vital ID, Aquatabs, Card Health Care Inc. 2019 Sabona, Sleep Pretty in Pink, Hearos, Ear Band-it, 4 Eyes, First Medic, Vita Medic, Kids Medic, Citrus Magic, Clearly Natural, Worlds Best. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 OR 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act Of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) April 9, 2014 THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ohio 1-434 31 -0411980 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission File (IRS Employer of incorporation) Number) Identification Number) One Procter & Gamble Plaza, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 (Address of principal executive offices) Zip Code (513) 983 -1100 45202 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Zip Code Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) ITEM 7.01 REGULATION FD DISCLOSURE On April 9, 2014, The Procter & Gamble Company (“Company”) and Mars, Incorporated (“Mars”) issued a news release announcing that the companies have reached an agreement for the sale of a significant portion of the Company’s pet food business to Mars. The Company is furnishing this 8-K pursuant to Item 7.01, "Regulation FD Disclosure." SIGNATURE Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the Registrant has duly caused this Report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned hereunto duly authorized. THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY BY: /s/ Susan S. -

News Release

News Release November 16, 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Franck Cordes, 202.357.5312 [email protected] Foundation for the National Archives Presents 2012 Heritage Award to Philanthropist Jacqueline Badger Mars Award presented at annual gala chaired by David M. Rubenstein Washington, DC – November 16, 2012 – The Foundation for the National Archives presented its first Heritage Award to philanthropist Jacqueline Badger Mars Tuesday November 13, at the Foundation’s annual black-tie gala. The event was chaired by David M. Rubenstein. Presenting sponsor was AT&T Services, Inc., with special thanks to the Maris S. Cuneo Foundation and the Eliasberg Family Foundation, Inc. The Heritage Award takes its name from the “Heritage” sculpture outside the National Archives Building and recognizes individuals, corporations, and organizations whose deeds are consistent with the Foundation’s mission of educating, enriching, and inspiring a deeper appreciation of our country’s heritage through the collected evidence of its history. A lifelong businesswoman, philanthropist, and advocate for women’s education, Jacqueline Mars was honored for her support of the National Archives as well as other arts and cultural institutions in Washington, DC. “We are so excited to present Jacquie with our first Heritage Award,” said Foundation President A’Lelia Bundles, who presented the award along with Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero. “We are inspired by Jacquie's personal passion for history and her commitment to preserving documents, books, and artifacts that celebrate our nation's heritage.” “Jaqueline Mars shares our passion for making historical records available to the public and preserving them for future generations,” said Ferriero. -

For Immediate Release Contacts: Sumitomo Corporation Expands

For Immediate Release Contacts: Ms. Jewelle Yamada Phone: 212-207-0574 E-mail: [email protected] Ms. Vanessa Goldschneider Phone: 212-207-0567 E-mail: [email protected] Sumitomo Corporation Expands Renewable Energy Portoflio as Sole Owner of Mesquite Creek Wind Farm in Texas Exclusive Long Term Agreement with Mars Inc. to Purchase Renewable Energy from Wind Farm New York, New York – April 30, 2014 – Sumitomo Corporation of Americas (SCOA) and Sumitomo Corporation (SC) (collectively Sumitomo) have acquired the remaining shares of the Mesquite Creek Wind Farm in Western Texas from co-developer BNB Renewable Energy (BNB) to achieve 100% ownership of the project. Sumitomo also announced that they have entered into a long-term agreement with Mars Inc. to purchase the renewable energy from the wind farm which will allow Mars to be effectively carbon neutral in their electricity consumption for 20+ years. Sumitomo secured financing for the project through funding from a syndicate of banks including, Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation and Mizuho Bank. “We are pleased to be partnered with Mars to help them reduce their carbon footprint and allow them to be carbon-neutral in the U.S. Mesquite Creek is a landmark project for Sumitomo and further stregthens our commitment to renewable energy and the U.S. market.”, said William Cannon, Vice President, Sumitomo Corporation of Americas. BNB, the originating developer of the project, entered into a joint venture with Sumitomo in August 2013 and they have since worked together to bring the 25,000 acre wind farm project to fruition. -

Mars Drinks Brings “A Barista” to the Workplace

MARS DRINKS BRINGS “A BARISTA” TO THE WORKPLACE NEW FLAVIA® BARISTA ESPRESSO BREWER INTRODUCES LEADING GLOBAL ESPRESSO BRAND TO THE WORKPLACE Company Reaches Agreement on Key Terms to Distribute Segafredo® Zanetti Internationally West Chester, PA (April 10, 2014) — Mars Drinks, a business unit of Mars, Incorporated, today announced the introduction of the design driven FLAVIA® BARISTA, a cutting-edge brewer with authentic espresso capability for the workplace. Available this fall in North America, the FLAVIA® BARISTA delivers the widest selection of authentically crafted coffeehouse-style hot beverages available now in the workplace. A game-changer for the market, the brewer features the required high pressure of up to 15-BARs to offer real, full-bodied, Italian espressos with thick, rich “crema” in 30-40 seconds. It also offers cappuccinos, lattes, teas, coffees and hot chocolates. To build on its authentic espresso capability, Mars Drinks has teamed with premier global coffee brand Segafredo Zanetti® and Massimo Zanetti Beverage Group to feature three Segafredo Zanetti® espresso blends with Mars Drinks’ FLAVIA® BARISTA brewer internationally. The FLAVIA® BARISTA brewer is part of Mars Drinks’ continuing commitment to provide innovative technologies and products for workplaces by making the booming global espresso experience accessible to associates right in their workplaces. “The right beverage experience is a catalyst for the kinds of moments that transform workplace culture. At Mars Drinks, we create great tasting moments that encourage collaboration and ideation in the workplace, and we are now excited to extend that proposition to include Segafredo Zanetti® espresso through our new FLAVIA® BARISTA brewer,” said Xavier Unkovic, global president, Mars Drinks. -

Eat Well Be Happy Organic

SIRI & SONS RALPH'S GREENHOUSE ORGANIC SPINACH BUNCHES 2 for $4 EAT WELL Save 99¢/ea BE HAPPY ORGANIC TOMATOES ORGANIC ON THE VINE MINI SEEDLESS WATERMELONS $2.49/lb Save $1/lb GREAT $1.19/lb DEAL Save $1.30/lb ORGANIC PINEAPPLE $1.99/lb Save 50¢/lb ORGANIC CANTALOUPE Recipe $1.19/lb INSIDE Save 50¢/lb ORGANIC KALE Purple · Green · Italian $1.99 Save 50¢/ea Organic Produce · On Sale 5/18 - 5/24 ORGANIC CRIMINI Wild Mushroom Calzones MUSHROOMS Pizza Dough Filling • 3 cups unbleached • 2 Tbsp butter $3.99/lb white flour, plus more • 1 yellow onion, chopped for kneading • 2 cloves garlic, minced Save $1/lb • 2 sprigs fresh rosemary • 3 slices bacon, cut leaves, minced into ½-inch pieces • 1 pkt (2 ¼ tsp) • ¾ lb mushrooms, sliced active dry yeast (We used crimini, maitake, • 1 tsp kosher salt and king trumpet) • 2 Tbsp olive oil, plus • Salt and pepper, to taste more for brushing • ½ cup marinara (We • 1 cup warm water (114°F) used Muir Glen) • 1 ½ cups mozzarella, ORGANIC shredded (We used Organic Valley) BRUSSELS SPROUTS Pizza Dough 1. In a large mixing bowl, whisk together flour, rosemary, yeast, $2.99/lb and kosher salt. Stir in olive oil and warm water. A shaggy Save $2/lb dough will form. 2. Turn dough out onto a floured surface. Knead for 3-4 minutes, until the dough becomes smooth and elastic. Add a little more flour to your hands and surface if it begins to stick. 3. Oil your mixing bowl. Place dough back into the bowl, and brush with a little more oil. -

Mars Food 2020 Purpose in Action Report Delivering Better Food Today

Mars Food 2020 Purpose in Action Report Delivering Better Food Today. A Better World Tomorrow Purpose in Action Report At Mars Food, everything we do is guided by our Purpose - Better Food Today. A Better World Tomorrow. As a food company, we know the power of dinnertimes. It’s and have used this position to inspire people to cook and more than just what is on our plates. We know that what we eat, eat together. In response to COIVD-19, we used our voice where it comes from and who we share it with are important. to remind people of the importance of eating together Creating better food today for a better world tomorrow has even when we’re far apart through our Special Guests never been more important than it is today as we face global communications. challenges that affect every one of us. • We have also made strong progress on our sustainability We believe that a better world tomorrow is one where commitments. In 2020, over 99% of our rice has been everyone has access to healthy meals, more people cook and sourced from farmers working towards the Sustainable sit down together to enjoy shared dinnertimes, and more Rice Platform Standard. This is not only good for the planet food can be produced with less. As a company, we have made but is also helping to support farmers on the pathway to some strong steps towards realizing this future and that is why economic stability. Results from our rice farmers in India and I am delighted to introduce our first annual Purpose in Action Pakistan for example have shown an 8% increase in yield, report. -

MMS 75Th Anniversary Press Release 030316 FINAL

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 800 HIGH STREET HACKETTSTOWN, NJ 07840 T+1 908 852 1000 F+1 908 850 2624 Contact: Katie Durkin Veronica Marshall Weber Shandwick Weber Shandwick 312.988.2444 312.988.2028 [email protected] [email protected] M&M’S® Turns 75 Years Young and Launches Year-Long Celebration for Fans America’s Favorite Chocolate Candy Invites Fans from Around the Globe to “Celebrate with M” with Star-Studded Partnerships, Product Innovation and Iconic Collaboration Hackettstown, N.J. (March 3, 2016) – M&M’S® Milk Chocolate Candies are the people’s chocolate. Since March 3, 1941, it is the fans who have made M&M’S the most popular chocolate candies on earth. To celebrate their anniversary, M&M’S is bringing the celebration to their fans - all year long. “For 75 years, our fans have made M&M’S the iconic and beloved chocolate brand it is today,” said Berta de Pablos-Barbier, Vice President, Marketing, Mars Chocolate North America. “We aren’t satisfied with solely looking back on our history as America’s favorite chocolate candies. We are looking to the next 75 years of innovation and transformation to engage, entice and excite consumers of today and tomorrow.” #CelebrateWithM A birthday celebration wouldn’t be complete without the guest of honor – and for M&M’S, that’s the fans! From weddings to birthdays and all occasions in between, M&M’S fans already celebrate with the brand every day. However, in 2016, M&M’S is taking the celebration up a notch with the launch of the largest marketing campaign in the brand’s history: “Celebrate with M.” The campaign will feature star-studded events, product innovation, iconic collaborations and unexpected partnerships that will cement the brand’s place in pop culture history. -

Mars Veterinary, Owner of the Wisdom Panel® Product Announces the Purchase of Assets Relating to the Canine Heritage™ Mixed Breed Dog Dna Identification Product

CONTACTS: Mars Veterinary 301-444-7900 [email protected] MARS VETERINARY, OWNER OF THE WISDOM PANEL® PRODUCT ANNOUNCES THE PURCHASE OF ASSETS RELATING TO THE CANINE HERITAGE™ MIXED BREED DOG DNA IDENTIFICATION PRODUCT Mars Veterinary™ has acquired the Canine Heritage XL Breed Test product previously offered by Scidera Canine LLC in the canine DNA breed identification market. The acquisition stems in part from the resolution of a patent infringement suit brought by Mars associated with its Wisdom Panel® canine DNA breed identification product. In order to ensure that customers who have purchased and submitted a Canine Heritage™ DNA test receive their results, Canine Heritage™ will coordinate processing the tests with Mars Veterinary™, the makers of Wisdom Panel® Family of Breed Identification tests, provided that the purchasers submit their dog's DNA swab within 90 days starting June 19, 2012. For more information regarding canine DNA Breed Identification, please visit Mars Veterinary's™ website at: www.wisdompanel.com. About Mars Veterinary™ Mars Veterinary is a division of MARS® Incorporated, a company known for innovative consumer and pet food brands that are trusted by people around the world. Its mission is to facilitate responsible pet care by enlightening pet owners and communities with valuable insights into their pets as individuals through innovative, science- based discoveries. For more than a decade, Mars Veterinary has researched and developed state-of-the-art genetic tests for mixed-breed dogs, revolutionizing personalized pet care. By discovering a dog’s ancestry, pet owners and veterinarians can work together to tailor wellness programs that fit the needs of a dog. -

CFS Shoppers' Guide

TRUE FOOD SHOPPER ’S GUIDE \How to Avoid Genetically Engineered Foods PROTECTING OUR FOOD, OUR FARMS & OUR ENVIRONMENT Which supermarket foods are genetically engineered? This is probably the most urgent question the public has about these novel foods. Opinion polls show that up to 90 percent of the American public wants GE foods labeled. But despite this overwhelming demand, almost no foods on U.S. grocery shelves reveal their secret, genetically engineered ingredients. We’ve seen that our government, under pressure from the biotechnology industry, has not required the labeling of GE foods. And the biotech industry does not voluntarily iden - ti fy them, fearing, probably correctly, that the majority of Americans would avoid GE foods if given a choice. As a result, the U.S. public has been deprived of its right to choose whether to buy and consume these engineered foods. However, this is not the case with most of our major trading partners around the globe who have instituted mandatory labeling of all GE foods and ingredients. This Non-GE Shopping Guide is designed to help you reclaim your right to know about the foods you are buying, and help you find and avoid GE foods. For more information on GE foods and what you can do to help, visit our website and join our True Food Network! www.centerforfoodsafety.org This Guide was compiled based on company statements sent to CFS and consumers; statements posted on compa - ny websites; and companies and products enrolled in the Non-GMO Project's non-GMO verification program. As ingredients in products change frequently, always check the packages—even of foods you buy often—to be sure to avoid non-organic at-risk ingredients.