Towards an Anatomy of Protracted Scientific Controversy: Perpetuated Negotiation in the 'Directed Mutation' Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Timeline of Significant Events in the Development of North American Mammalogy

SpecialSpecial PublicationsPublications MuseumMuseum ofof TexasTexas TechTech UniversityUniversity NumberNumber xx66 21 Novemberxx XXXX 20102017 A Timeline of SignificantTitle Events in the Development of North American Mammalogy Molecular Biology Structural Biology Biochemistry Microbiology Genomics Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Computer Science Statistics Physical Chemistry Information Technology Mathematics David J. Schmidly, Robert D. Bradley, Lisa C. Bradley, and Richard D. Stevens Front cover: This figure depicts a chronological presentation of some of the significant events, technological breakthroughs, and iconic personalities in the history of North American mammalogy. Red lines and arrows depict the chronological flow (i.e., top row – read left to right, middle row – read right to left, and third row – read left to right). See text and tables for expanded interpretation of the importance of each person or event. Top row: The first three panels (from left) are associated with the time period entitled “The Emergence Phase (16th‒18th Centuries)” – Mark Catesby’s 1748 map of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Willson Peale; the next two panels represent “The Discovery Phase (19th Century)” – Spencer Fullerton Baird and C. Hart Merriam. Middle row: The first two panels (from right) represent “The Natural History Phase (1901‒1960)” – Joseph Grinnell and E. Raymond Hall; the next three panels (from right) depict “The Theoretical and Technological Phase (1961‒2000)” – illustration of Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson’s theory of island biogeography, karyogram depicting g-banded chromosomes, and photograph of electrophoretic mobility of proteins from an allozyme analysis. Bottom row: These four panels (from left) represent the “Big Data Phase (2001‒present)” – chromatogram illustrating a DNA sequence, bioinformatics and computational biology, phylogenetic tree of mammals, and storage banks for a supercomputer. -

What the Modern Age Knew Piero Scaruffi 2004

A History of Knowledge Oldest Knowledge What the Jews knew What the Sumerians knew What the Christians knew What the Babylonians knew Tang & Sung China What the Hittites knew What the Japanese knew What the Persians knew What the Muslims knew What the Egyptians knew The Middle Ages What the Indians knew Ming & Manchu China What the Chinese knew The Renaissance What the Greeks knew The Industrial Age What the Phoenicians knew The Victorian Age What the Romans knew The Modern World What the Barbarians knew 1 What the Modern Age knew Piero Scaruffi 2004 1919-1945: The Age of the World Wars 1946-1968: The Space Age 1969-1999: The Digital Age We are not shooting enough professors An eye for an eye makes (Lenin’s telegram) the whole world blind. (Mahatma Gandhi) "Pacifism is objectively pro-Fascist.” (George Orwell, 1942) "The size of the lie is a definite factor What good fortune for governments in causing it to be believed" that the people do not think (Adolf Hitler, "Mein Kampf") (Adolf Hitler) 2 What the Modern Age knew • Bibliography – Paul Kennedy: The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987) – Jacques Barzun: "From Dawn to Decadence" (2001) – Gregory Freeze: Russia (1997) – Andrzej Paczkowski: The Black Book of Communism (1999) – Peter Hall: Cities in Civilization (1998) – Edward Kantowicz: The World In The 20th Century (1999) – Paul Johnson: Modern Times (1983) – Sheila Jones: The Quantum Ten (Oxford Univ Press, 2008) – Orlando Figes: “Natasha's Dance - A Cultural History of Russia” (2003) 3 What the Modern Age knew • Bibliography – -

Some Observations on Avoiding Pitfalls in Developing Future Flight Systems

AIAA 97-3209 Some Observations on Avoiding Pitfalls in Developing Future Flight Systems Gary L. Bennett Metaspace Enterprises Emmett, Idaho; U.S.A. 33rd AIAA/ASME/SAEIASEEJoint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit July 6 - 9, 1997 I Seattle, WA For permission to copy or republish, contact the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1801 Alexander Bell Drive, Suite 500, Reston, VA 22091 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON AVOIDING PITFALLS IN DEVELOPING FUTURE FLIGHT SYSTEMS Gary L. Bennett* 5000 Butte Road Emmett, Idaho 83617-9500 Abstract Given the speculative proposals and the interest in A number of programs and concepts have been developing breakthrough propulsion systems it seems proposed 10 achieve breakthrough propulsion. As an prudent and appropriate to review some of the pitfalls cautionary aid 10 researchers in breakthrough that have befallen other programs in "speculative propulsion or other fields of advanced endeavor, case science" so that similar pitfalls can be avoided in the histories of potential pitfalls in scientific research are future. And, given the interest in UFO propulsion, described. From these case histories some general some guidelines to use in assessing the reality of UFOs characteristics of erroneous science are presented. will also be presented. Guidelines for assessing exotic propulsion systems are suggested. The scientific method is discussed and some This paper will summarize some of the principal tools for skeptical thinking are presented. Lessons areas of "speculative science" in which researchers learned from a recent case of erroneous science are were led astray and it will then provide an overview of listed. guidelines which, if implemented, can greatly reduce Introduction the occurrence of errors in research. -

Karl Jordan: a Life in Systematics

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Kristin Renee Johnson for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of SciencePresented on July 21, 2003. Title: Karl Jordan: A Life in Systematics Abstract approved: Paul Lawrence Farber Karl Jordan (1861-1959) was an extraordinarily productive entomologist who influenced the development of systematics, entomology, and naturalists' theoretical framework as well as their practice. He has been a figure in existing accounts of the naturalist tradition between 1890 and 1940 that have defended the relative contribution of naturalists to the modem evolutionary synthesis. These accounts, while useful, have primarily examined the natural history of the period in view of how it led to developments in the 193 Os and 40s, removing pre-Synthesis naturalists like Jordan from their research programs, institutional contexts, and disciplinary homes, for the sake of synthesis narratives. This dissertation redresses this picture by examining a naturalist, who, although often cited as important in the synthesis, is more accurately viewed as a man working on the problems of an earlier period. This study examines the specific problems that concerned Jordan, as well as the dynamic institutional, international, theoretical and methodological context of entomology and natural history during his lifetime. It focuses upon how the context in which natural history has been done changed greatly during Jordan's life time, and discusses the role of these changes in both placing naturalists on the defensive among an array of new disciplines and attitudes in science, and providing them with new tools and justifications for doing natural history. One of the primary intents of this study is to demonstrate the many different motives and conditions through which naturalists came to and worked in natural history. -

Representatives and Committees of the Society

REPRESENTATIVES AND COMMITTEES OF THE SOCIETY Representatives of the Society in the Division of Physical Sciences of the National Research Council: 1944-1945—Marston Morse, M. H. Stone, Warren Weaver. 1945-1946—A. B. Coble, G. A. Hedlund, Saunders MacLane, Marston Morse, Oswald Veblen, Warren Weaver. 1946-1947—A. B. Coble, Saunders MacLane, John von Neumann, M. H. Stone, Oswald Veblen, Warren Weaver. 1947-1948—R. V. Churchill, M. R. Hestenes, Saunders MacLane, John von Neu mann, M. H. Stone, Oswald Veblen. Representatives on the Council of the American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1945—R. P. Agnew, M. R. Hestenes. 1946—Philip Franklin, C. V. Newsom. 1947—Solomon Lefschetz, G. T. Whyburn. Representatives on the Editorial Board of the Annals of Mathematics: K. 0. Friedrichs, Norman Levinson, R. L. Wilder. Representatives on the Editorial Board of the Duke Mathematical Journal: F. J. Murray, Morgan Ward. Representative on the American Year Book: G. T. Whyburn. Liaison Officer in Connection with Editorial Management of Quarterly of Applied Mathematics: Einar Hille. Colloquium Speakers: 1944—Einar Hille. 1946—Hassler Whitney. 1945—Tibor Rado. 1947—Oscar Zariski. Committee to Select Gibbs Lecturers for 1946 and 1947: L. M. Graves (Chairman), G. A. Hedlund, S. S. Wilks. Gibbs Lecturers: 1923—M. I. Pupin. 1930—E. B. Wilson. 1939—Theodore von Kârmân. 1924—Robert Henderson. 1931—P. W. Bridgman. 1941—Sewall Wright. 1925—James Pierpont. 1932—R. C. Tolman. 1943—Harry Bateman. 1926—H. B. Williams. 1934—Albeit Einstein. 1944—John von Neumann. 1927-E. W. Brown. 1935—Vannevar Bush. 1945—J. C. Slater. 1928—G. -

Roles for Socially-Engaged Philosophy of Science in Environmental Policy

Roles for Socially-Engaged Philosophy of Science in Environmental Policy Kevin C. Elliott Lyman Briggs College, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, and Department of Philosophy, Michigan State University Introduction The philosophy of science has much to contribute to the formulation of public policy. Contemporary policy making draws heavily on scientific information, whether it be about the safety and effectiveness of medical treatments, the pros and cons of different economic policies, the severity of environmental problems, or the best strategies for alleviating inequality and other social problems. When science becomes relevant to public policy, however, it often becomes highly politicized, and figures on opposing sides of the political spectrum draw on opposing bodies of scientific information to support their preferred conclusions.1 One has only to look at contemporary debates over climate change, vaccines, and genetically modified foods to see how these debates over science can complicate policy making.2 When science becomes embroiled in policy debates, questions arise about who to trust and how to evaluate the quality of the available scientific evidence. For example, historians have identified a number of cases where special interest groups sought to influence policy by amplifying highly questionable scientific claims about public-health and environmental issues like tobacco smoking, climate change, and industrial pollution.3 Determining how best to respond to these efforts is a very important question that cuts across multiple -

Breaking the Siege: Guidelines for Struggle in Science Brian Martin Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, NSW 2522 [email protected]

Breaking the siege: guidelines for struggle in science Brian Martin Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, NSW 2522 http://www.bmartin.cc/ [email protected] When scientists come under attack, it is predictable that the attackers will use methods to minimise public outrage over the attack, including covering up the action, devaluing the target, reinterpreting what is happening, using official processes to give an appearance of justice, and intimidating people involved. To be effective in countering attacks, it is valuable to challenge each of these methods, namely by exposing actions, validating targets, interpreting actions as unfair, mobilising support and not relying on official channels, and standing up to intimidation. On a wider scale, science is constantly under siege from vested interests, especially governments and corporations wanting to use scientists and their findings to serve their agendas at the expense of the public interest. To challenge this system of institutionalised bias, the same sorts of methods can be used. ABSTRACT Key words: science; dissent; methods of attack; methods of resistance; vested interests Scientists and science under siege In 1969, Clyde Manwell was appointed to the second chair environmental issues?” (Wilson and Barnes 1995) — and of zoology at the University of Adelaide. By present-day less than one in five said no. Numerous environmental terminology he was an environmentalist, but at the time scientists have come under attack because of their this term was little known and taking an environmental research or speaking out about it (Kuehn 2004). On stand was uncommon for a scientist. Many senior figures some topics, such as nuclear power and fluoridation, it in government, business and universities saw such stands can be very risky for scientists to take a view contrary as highly threatening. -

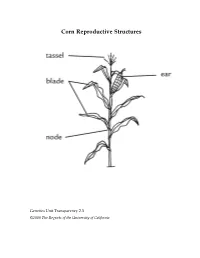

Corn Reproductive Structures

Corn Reproductive Structures Genetics Unit Transparency 2.3 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Creating a Punnett Square Genetics Unit Transparency 2.4 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Case Study Summary Sheet Case Study Type of Benefits Risks and concerns Remaining questions Genetic Modification Genetics Unit Transparency 4.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Class Data for Rice Breeding Simulation aromatic, non-aromatic, aromatic, non-aromatic ,flood-tolear nt flood-tolerant flood-intolerant flood-intolerant AAFF AAFf AaFF AaFf aaFF aaFf AAff Aaff aaff Group 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Genetics Unit Transparency 5.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Three Types of Cells Genetics Unit Transparency 6.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California DNA base percentages in a variety of organisms Source of A T G C DNA Human 31.0% 31.5% 19.1% 18.4% Mouse 29.1% 29.0% 21.1% 21.1% Frog 26.3% 26.4% 23.5% 23.8% Fruit fly 27.3% 27.6% 22.5% 22.5% Corn 25.6% 25.3% 24.5% 24.6% E. coli 24.6% 24.3% 25.5% 25.6% Genetics Unit Transparency 7.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl’s Experiment to Investigate DNA Replication First: Scientists James Watson and Francis Crick propose a method of semi-conservative replication in their paper on the structure of DNA. However, they have no data to support their hypothesis. Next: Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl use the procedure that follows to investigate DNA created by the process of DNA Replication. -

The Role of Participation in a Techno-Scientific Controversy

PARTICIPATORY GOVERNANCE AND INSTITUTIONAL INNOVATION Participatory Governance and Institutional Innovation [PAGANINI] Contract No. CIT2-CT-2004-505791 . Deliverable Number 16 Work Package 6 _ GM Food THE ROLE OF PARTICIPATION IN A TECHNO-SCIENTIFIC CONTROVERSY Larry Reynolds and Bronislaw Szerszynski with Maria Kousis and Yannis Volakakis 6th EU Framework Programme for Research and Technology Participatory Governance and Institutional Innovation [PAGANINI] Contract No. CIT2-CT-2004-505791 . Deliverable Number 16 WORK PACKAGE 6 _ GM FOOD THE ROLE OF PARTICIPATION IN A TECHNO-SCIENTIFIC CONTROVERSY Larry Reynolds and Bronislaw Szerszynski with Maria Kousis and Yannis Volakakis 1 The Paganini Project Focussing on selected key areas of the 6th EU Framework Programme for Research and Technology, PAGANINI investigates the ways in which participatory practices contribute to problem solving in a number of highly contentious fields of EU governance. PAGANINI looks at a particular dynamic cluster of policy areas concerned with what we call “the politics of life”: medicine, health, food, energy, and environment. Under “politics of life” we refer to dimensions of life that are only to a limited extent under human control - or where the public has good reasons to suspect that there are serious limitations to socio-political control and steering. At the same time, “politics of life” areas are strongly connected to normative, moral and value-based factors, such as a sense of responsibility towards the non-human nature, future generations and/or one‟s -

EUGENICS, HUMAN GENETICS and HUMAN FAILINGS the Eugenics Society, Its Sources and Its Critics in Britain Pauline M.H.Mazumdar

EUGENICS, HUMAN GENETICS AND HUMAN FAILINGS The Eugenics Society, its sources and its critics in Britain Pauline M.H.Mazumdar London and New York 1992 CONTENTS List of illustrations vii Preface x INTRODUCTION 1 1 THE EUGENICS EDUCATION SOCIETY: THE TRADITION, THE 5 SETTING AND THE PROGRAMME 2 THE AGE OF PEDIGREES: THE METHODOLOGY OF EUGENICS, 40 1900–20 3 IDEOLOGY AND METHOD: R.A.FISHER AND RESEARCH IN 69 EUGENICS 4 THE ATTACK FROM THE LEFT: MARXISM AND THE NEW 106 MATHEMATICAL TECHN JQUES 5 HUMAN GENETICS AND THE EUGENICS PROBLEMATIC 142 EPILOGUE AND CONCLUSION 184 Notes 193 Bibliography 232 Frontispiece Pedigree of the Wedgwood-Darwin-Galton family, the model family of the eugenics movement EUGENICS, HUMAN GENETICS AND HUMAN FAILINGS What is the history of the British eugeriics movement? Why should it be of interest to how scientists work today? This outstanding study follows the history of the eugeriics movements from its roots to its heyday as the source of a science of human genetics. The primary contributions of the book are fourfold. First, it points to nineteenth-century social reform as contributing to the later eugenics movement. Second, it is based upon important archival material newly available to researchers. This material gives the reader an insight into the inner councils of the Society that could not have been obtained by relying upon published sources alone. Third, it treats the statistical methods involved in human genetics historically, in a way that allows the reader to follow their development and tie them to their context within the eugenics movement. -

Rhetoric for Becoming Otherwise

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts RHETORIC FOR BECOMING OTHERWISE: LIFE, LITERATURE, GENEALOGY, FLIGHT A Dissertation in English by Abram D. Anders © 2009 Abram D. Anders Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 ii The dissertation of Abram D. Anders was reviewed and approved* by the following: Richard M. Doyle Professor of English and Science, Technology and Society Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Jeffrey T. Nealon Liberal Arts Research Professor of English Xiaoye You Assistant Professor of English and Asian Studies Robert A. Yarber, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Art Robert R. Edwards Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English and Comparative Literature Department of English Graduate Director *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT Rhetoric for Becoming Otherwise begins with the Isocratean premise that thought, speech, writing are best understood as bridges between the already said of language and the emerging circumstances that are the occasions for their production. This argument is rehearsed across a variety of domains and instances following Isocrates exhortation that the rhetorician or practitioner of philosophia can only model the movement of discourse without expecting to provide any “true knowledge” or “absolute theory” for how to encounter the problematics of an endlessly deferred present. As a matter of rhetoric, becoming otherwise is the continually renewed task of creating something new from the resources of language and for the demands of an ever deferred present—Presocratics versus Classicists (Chapter 1). As a matter of health, becoming otherwise is the necessity of overcoming limitation and suffering in order to achieve new norms of health and pursue the ever changing opportunities of a self‐developing capacity for producing new capacities—Normativity versus Normalization (Chapter 2). -

The Argument Form “Appeal to Galileo”: a Critical Appreciation of Doury's Account

The Argument Form “Appeal to Galileo”: A Critical Appreciation of Doury’s Account MAURICE A. FINOCCHIARO Department of Philosophy University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas, NV 89154-5028 USA [email protected] Abstract: Following a linguistic- Résumé: En poursuivant une ap- descriptivist approach, Marianne proche linguistique-descriptiviste, Doury has studied debates about Marianne Doury a étudié les débats “parasciences” (e.g. astrology), dis- sur les «parasciences » (par exem- covering that “parascientists” fre- ple, l'astrologie), et a découvert que quently argue by “appeal to Galileo” les «parasavants» raisonnent souvent (i.e., defend their views by compar- en faisant un «appel à Galilée" (c.-à- ing themselves to Galileo and their d. ils défendent leurs points de vue opponents to the Inquisition); oppo- en se comparant à Galileo et en nents object by criticizing the analo- comparant leurs adversaires aux gy, charging fallacy, and appealing juges de l’Inquisition). Les adver- to counter-examples. I argue that saires des parasavant critiquent Galilean appeals are much more l'analogie en la qualifiant de soph- widely used, by creationists, global- isme, et en construisant des contre- warming skeptics, advocates of “set- exemples. Je soutiens que les appels tled science”, great scientists, and à Galilée sont beaucoup plus large- great philosophers. Moreover, sever- ment utilisés, par des créationnistes, al subtypes should be distinguished; des sceptiques du réchauffement critiques questioning the analogy are planétaire, des défenseurs de la «sci- proper; fallacy charges are problem- ence établie», des grands scien- atic; and appeals to counter- tifiques, et des grands philosophes. examples are really indirect critiques En outre, on doit distinguer plusieurs of the analogy.