Of Rauschenberg, Policy and Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017

The Museum of Modern Art Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017 Stop List 800. Introduction 801. Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, Double Rauschenberg, c. 1950 802. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Black Painting with Asheville Citizen), c. 1952 8021. Underneath Asheville Citizen 803. Robert Rauschenberg, White Painting, 1951, remade 1960s 804. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Scatole personali) (Personal boxes), 1952-53 805. Robert Rauschenberg with John Cage, Automobile Tire Print, 1953 806. Robert Rauschenberg with Willem de Kooning and Jasper Johns, Erased de Kooning, 1953 807. Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955 8071. Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines 808. Robert Rauschenberg, Minutiae, 1954 809. Robert Rauschenberg, Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante's Inferno, 1958-60 810. Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959 811. Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-59 812. Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960 813. Robert Rauschenberg, Trophy IV (for John Cage), 1961 814. Robert Rauschenberg, Homage to David Tudor (performance), 1961 815. Robert Rauschenberg, Pelican, (performance), 1963 USA20415F – MoMA – Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Script 1 816. Robert Rauschenberg, Retroactive I, 1965 817. Robert Rauschenberg, Oracle, 1962-65 818. Robert Rauschenberg with Carl Adams, George Carr, Lewis Ellmore, Frank LaHaye, and Jim Wilkinson, Mud Muse, 1968-71 819. John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol with Fred Waldhauer, The Moon Museum, 1969 820. Robert Rauschenberg, 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, 1966 (Poster, ephemera) 821. Robert Rauschenberg, Cardboards, 1971-1972 822. Robert Rauschenberg, Jammers (series), 1974-1976 823. Robert Rauschenberg, Glut (series), 1986-97 824. Robert Rauschenberg, Glacial Decoy (series of 620 slides and film), 1979 825. -

Marian Penner Bancroft Rca Studies 1965

MARIAN PENNER BANCROFT RCA STUDIES 1965-67 UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, Arts & Science 1967-69 THE VANCOUVER SCHOOL OF ART (Emily Carr University of Art + Design) 1970-71 RYERSON POLYTECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, Toronto, Advanced Graduate Diploma 1989 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, Visual Arts Summer Intensive with Mary Kelly 1990 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, short course with Griselda Pollock SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, upcoming in May 2019 WINDWEAVEWAVE, Burnaby, BC, video installation, upcoming in May 2018 HIGASHIKAWA INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL GALLERY, Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan, Overseas Photography Award exhibition, Aki Kusumoto, curator 2017 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, RADIAL SYSTEMS photos, text and video installation 2014 THE REACH GALLERY & MUSEUM, Abbotsford, BC, By Land & Sea (prospect & refuge) 2013 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HYDROLOGIC: drawing up the clouds, photos, video and soundtape installation 2012 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, SPIRITLANDS t/Here, Grant Arnold, curator 2009 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, CHORUS, photos, video, text, sound 2008 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HUMAN NATURE: Alberta, Friesland, Suffolk, photos, text installation 2001 CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver THE MENDEL GALLERY, Saskatoon SOUTHERN ALBERTA ART GALLERY, Lethbridge, Alberta, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) 2000 GALERIE DE L'UQAM, Montreal, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver, VISIT 1999 PRESENTATION HOUSE GALLERY, North Vancouver, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) UNIVERSITY -

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol. 44 Issue 97 While the Artery is providing this newsletter as a courtesy service, every effort is made to ensure that information listed below is timely and accurate. However we are unable to guarantee the accuracy of information and functioning of all links. INDEX # ON AT THE GALLERY: Exhibition My Vintage Rubble and Fish & Moose series 1 Mini-retrospective by Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wednesday, Feb 1, 6:30 pm EVENTS AROUND TOWN EVENTS 2-6 EXHIBITIONS 7-24 THEATRE 25/26 WORKSHOPS 27-30 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS LOCAL EXHIBITIONS 31 GRANTS 32 MISCELLANEOUS 33 PUBLIC ART 34 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS NATIONAL AWARDS 35 EXHIBITIONS 36-44 FAIR 45/46 FESTIVAL 47-49 JOB CALL 50-56 CALL FOR PARTICPATION 57 PERFORMANCE 58 CONFERENCE 59 PUBLIC ART 60-63 RESIDENCY 64-69 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS INTERNATIONAL WEBSITE 70 BY COUNTRY ARGENTINA RESIDENCY 71 AUSTRIA PRIZE 72 BRAZIL RESIDENCY 73/74 CANADA RESIDENCY 75-79 FRANCE RESIDENCY 80/81 GERMANY RESIDENCY 82 ICELAND PERFORMERS 83 INDIA RESIDENCY 84 IRELAND FESTIVAL 85 ITALY FAIR 86 RESIDENCY 87-89 MACEDONIA RESIDENCY 90 MEXICO RESIDENCY 91/92 MOROCCO RESIDENCY 93 NORWAY RESIDENCY 94 PANAMA RESIDENCY 95 SPAIN RESIDENCY 96 RETREAT 97 UK RESIDENCY 98/99 USA COMPETITION 100 EXHIBITION 101 FELLOWSHIP 102 RESIDENCY 103-07 BRITANNIA ART GALLERY: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: 108 SUBMISSIONS TO THE ARTERY E-NEWSLETTER 109 VOLUNTEER RECOGNITION 110 GALLERY CONTACT INFORMATION 111 ON AT BRITANNIA ART GALLERY 1 EXHIBITIONS: February 1 - 24 My Vintage Rubble, Fish and Moose series – Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wed. -

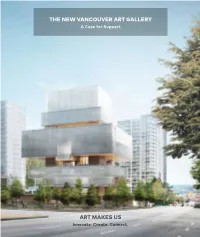

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY a Case for Support

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY A Case for Support A GATHERING PLACE for Transformative Experiences with Art Art is one of the most meaningful ways in which a community expresses itself to the world. Now in its ninth decade as a significant contributor The Gallery’s art presentations, multifaceted public to the vibrant creative life of British Columbia and programs and publication projects will reflect the Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has embarked on diversity and vitality of our community, connecting local a transformative campaign to build an innovative and ideas and stories within the global realm and fostering inspiring new art museum that will greatly enhance the exchanges between cultures. many ways in which citizens and visitors to the city can experience the amazing power of art. Its programs will touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, through remarkable, The new building will be a creative and cultural mind-opening experiences with art, and play a gathering place in the heart of Vancouver, unifying substantial role in heightening Vancouver’s reputation the crossroads of many different neighbourhoods— as a vibrant place in which to live, work and visit. Downtown, Yaletown, Gastown, Chinatown, East Vancouver—and fuelling a lively hub of activity. For many British Columbians, this will be the most important project of their Open to everyone, this will be an urban space where museum-goers and others will crisscross and encounter generation—a model of civic leadership each other daily, and stop to take pleasure in its many when individuals come together to build offerings, including exhibitions celebrating compelling a major new cultural facility for its people art from the past through to artists working today— and for generations of children to come. -

New Year's in Vancouver

NEW YEAR’S IN Activity Level: 1 VANCOUVER December 30, 2021 – 4 Days 1 Dinner Included With Salute to Vienna concert at Orpheum Fares per person: $1,470 double/twin; $1,825 single; $1,420 triple Please add 5% GST. Ring in 2022 in style and enjoy the annual performance of Salute to Vienna presented Early Bookers: $60 discount on first 15 seats; $30 on next 10 by the Vancouver Symphony. It has an Experience Points: outstanding cast of 75 musicians, singers, Earn 32 points on this tour. and dancers, and has been billed as the Redeem 32 points if you book by October 27, 2021. world’s greatest New Year’s concert. We Departure from: Victoria have reserved superb seats in the Centre Orchestra of the Orpheum Theatre. Two other shows are also included, but most theatre companies are still emerging from Covid shutdowns and planning their fall and winter schedules. A morning at the Vancouver Art Gallery is included. The tour stays 3 nights at the renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver. Salute to Vienna ITINERARY Day 1: Thursday, December 30 such as the Gateway or Granville Island Stage. Transportation is provided mid-day to the Again, if you are not interested in attending, you renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver and we stay can opt out and your fare will be reduced. We three nights. Opened in 1939 at a cost of $12 return to the hotel after the show, then at million, it was the third Hotel Vancouver and a midnight you may want to celebrate the arrival of downtown landmark with its copper green roof 2022 in the hotel lounge or nearby. -

Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’S 2016 Media Kit

Assignment: Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’s 2016 Media Kit TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 4 WHERE IN THE WORLD IS VANCOUVER? ........................................................ 4 VANCOUVER’S TIMELINE.................................................................................... 4 POLITICALLY SPEAKING .................................................................................... 8 GREEN VANCOUVER ........................................................................................... 9 HONOURING VANCOUVER ............................................................................... 11 VANCOUVER: WHO’S COMING? ...................................................................... 12 GETTING HERE ................................................................................................... 13 GETTING AROUND ............................................................................................. 16 STAY VANCOUVER ............................................................................................ 21 ACCESSIBLE VANCOUVER .............................................................................. 21 DIVERSE VANCOUVER ...................................................................................... 22 WHERE TO GO ............................................................................................................... 28 VANCOUVER NEIGHBOURHOOD STORIES ................................................... -

THE DIGITAL DOMAIN NO. 3: Selected Internet Visual Resources for the Study of British Columbia - Arty Photography, and Multimedia

THE DIGITAL DOMAIN NO. 3: Selected Internet Visual Resources for the Study of British Columbia - Arty Photography, and Multimedia COMPILED BY DAVID MATTISON Access Services Archivist, BC Archives, Victoria his compilation lists publicly accessible Internet image collections documenting BC's pictorial heritage in the form T of selected artwork, photographs, and multimedia (combi nations of text, still images, and audio-video) Web sites. Architecture and cartography resources will be described in a future Digital Domain. Non-image-based Internet sites such as the George Eastman House photography database are also included because they document the existence of images held by institutions. Organizations such as the Vancouver Cultural Alliance which promote access to arts resources, but do not necessarily feature reproductions from the visual arts arena, are also included. Due to space limitations and the vast amount of visual material on the Internet, this listing is not inclusive. The majority of references in this bibliography are to Web sites whose URL (Universal/Uniform Resource Locator) or Internet address always begins with http://. In order to prevent confusion and because the URL must include the service designator, the Web designator is shown. The two most popular graphical Web browsers, Microsoft Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator, both default to a Web URL when the service designator is not included. Those using the Internet through a proxy server or who have cookies disabled may encounter problems with some of these resources. You are encouraged to contact your Internet Service Provider (ISP) if you have problems connecting with a particular Web site or Internet computer system, or if you need general assistance in configuring your Web browser and any associated software required to access these resources. -

SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS of CIRCLES Through the Art of JOCK MACDONALD

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE FOR GRADES 8–11 LEARN ABOUT SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS OF CIRCLES through the art of JOCK MACDONALD Click the right corner to SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS OF CIRCLES JOCK MACDONALD through the art of return to table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 RESOURCE WHO WAS JOCK TIMELINE OF OVERVIEW MACDONALD? HISTORICAL EVENTS AND ARTIST’S LIFE PAGE 4 PAGE 8 PAGE 10 LEARNING CULMINATING HOW JOCK MACDONALD ACTIVITIES TASK MADE ART: STYLE & TECHNIQUE PAGE 11 READ ONLINE DOWNLOAD ADDITIONAL JOCK MACDONALD: JOCK MACDONALD RESOURCES LIFE & WORK IMAGE FILE BY JOYCE ZEMANS EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE SHADING TECHNIQUES & MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS OF CIRCLES through the art of JOCK MACDONALD RESOURCE OVERVIEW This teacher resource guide has been designed to complement the Art Canada Institute online art book Jock Macdonald: Life & Work by Joyce Zemans. The artworks within this guide and images required for the learning activities and culminating task can be found in the Jock Macdonald Image File provided. These activities were prepared with Laura Briscoe & Jeni Van Kesteren of Art of Math Education. Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) was one of the most radical artists in Canada in the mid-twentieth century. In the 1930s he began experimenting with abstraction, a quest that led him to many different disciplines. As author Joyce Zemans has noted, he was “guided by the most current discussions of art and aesthetics and of mathematical and scientific theories.” In the spirit of Macdonald’s works, the activities in this guide connect visual arts and mathematics. This connection will make Macdonald’s art more engaging for students and inspire a creative, personalized approach to understanding mathematical concepts of circles. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Alley Cat Rentals Artina’s (Victoria), 127 AAA Horse & Carriage Ltd. (Vancouver), 87 Artisans Courtyard (Vancouver), 82 Alliance for Arts and Culture (Courtenay), 198 Abandoned Rails Trail, 320 (Vancouver), 96 Artisan’s Studio (Nanaimo), Aberdeen Hills Golf Links Allura Direct (Whistler), 237 169 (Kamloops), 287 Alpha Dive Services (Powell Art of Man Gallery (Victoria), Abkhazi Garden (Victoria), River), 226 126 119 Alpine Rafting (Golden), 323 The Arts Club Backstage Access-Able Travel Source, 42 Alta Lake, 231 Lounge (Vancouver), 100 Accessible Journeys, 42 American Airlines, 36 Arts Club Theatre Company Active Pass (between Galiano American Automobile Asso- (Vancouver), 97 from Mayne islands), 145 ciation (AAA), 421 Asulkan Valley Trail, 320 Adam’s Fishing Charters American Express Athabasca, Mount, 399 (Victoria), 122 Calgary, 340 Athabasca Falls, 400 Adams River Salmon Run, Edmonton, 359 Athabasca Glacier, 400 286 American Foundation for the Atlantic Trap and Gill Adele Campbell Gallery Blind (AFB), 42 (Vancouver), 99 (Whistler), 236 Anahim Lake, 280 Au Bar (Vancouver), 101 Admiral House Boats Ancient Cedars area of Cougar Aurora (Banff), 396 (Sicamous), 288 Mountain, 235 Avello Spa (Whistler), 237 Adventure Zone (Blackcomb), Ancient Cedars Spa (Tofino), 236 189 Afterglow (Vancouver), 100 Anglican Church abine Mountains Recre- Agate Beach Campground, B Alert Bay, 218 ation Area, 265 258 Barkerville, 284 Backpacking, 376 Ah-Wa-Qwa-Dzas (Quadra A-1 Last Minute Golf Hot Line Backroom Vodka Bar Island), 210 (Vancouver), 88 (Edmonton), -

The Evolution of Municipal Government Arts Policy in Vancouver

kquisi'rlons 3rd Dmction des acqut:;r!ions et Bib5og;apiric Services Brm& rigs serwsces bibitwiaphrques 395 't,'ei,qI~slStas: .335. rue L%'elfrigtz>.? ~z,.*G, 0:4~.,.ln..a-.*.?. 1~rlns-t.J..&n:W: . K 1 A ~pg M 3. n ~% .cL%~15i.r * A ' ,.,,, , 2.. %.,,!:. .pa..\, .. *, i. quality of this microform is La qualitk de cette microforme heavily dependeni upon the depend grandernent de la qualite qwiity ~f the originat thesis de la th6se soilmise au submitfed for microfilming. microfiimage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualite ensure the highest quality of superieure de reproduction. reproduct ion possibk. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec I'universite degree. qui a confere le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualit4 d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser a pages were typed with a poor dbsirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont a6 university sent us an inferior dactylographiees a I'aide d'un photocopy. ruban use ou si I'universitb nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualite infkrieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, meme partielle, tk;e,, ,,, ,,,,,,m;nrninrm ,,,, ,,, is governed by de cette microforme esf soumlse the Canadian Copyright Act, a la Loi canadienne sur ie droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30,et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subsequents. THE POLITICS OF LOCAL CULTERE: THE EVOLUTION OF MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT ARTS POLICY fM VANCOUVER Susan Juliet Stevenson B.A., McGiil University 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFiLLMENT OF REQUIRmNTS FOR THE DEGREE OF OF ARTS in &he Department of Communication O Susan Stevenson SIMCIN FmSER UNIVERSITY September 1992 All rights reserved. -

Vancouver Art Gallery Announces New Members of Board of Trustees

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE VANCOUVER ART GALLERY ANNOUNCES NEW MEMBERS OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES VANCOUVER, BC (November 20, 2019) – The Vancouver Art Gallery announced at its Annual General Meeting on November 13, 2019, the appointment of three new Trustees to its Board, Leah George-Wilson, Salia Joseph and Jessica Yan-Macintosh. “Each of the new Trustees bring inspiration, experience and diversity of thought to the Vancouver Art Gallery,” said Vancouver Art Gallery Board Secretary and Chair, Governance/Nominations, Hank Bull. “These individuals are community leaders committed to the growth of the arts in Vancouver and will play a vital role in the continuing evolution of the Vancouver Art Gallery, helping lead the organization forward.” At the Annual General Meeting, Board of Trustees, Chair, David Calabrigo welcomed the new Trustees, bringing the count of voting members to 20. A complete list of the Board of Trustees can be found on the Vancouver Art Gallery website at www.vanartgallery.bc.ca/leadership. “We are truly fortunate to welcome these stellar individuals to the organization. They join a group of committed and passionate Trustees whose breadth of knowledge will help the Gallery strategically,” shared Interim Vancouver Art Gallery Director, Daina Augaitis. “Combined with their unflagging belief in the work that the Gallery does, I am confident that they will help us achieve our goals.” ABOUT THE NEW TRUSTEES Leah George-Wilson is a Chief at Tsleil Waututh Nation and was the first woman to serve this position. She is also a lawyer practicing in the area of Indigenous law at Miller Titerle + Co. George-Wilson is also the elected co-chair of the First Nations Summit, a director on the Land Advisory Board and an appointed board member of the First Nations Health Council. -

The Transformation of the Vancouver Art Gallery

A 2017 PRE-BUDGET SUBMISSION TO THE HOUSE OF COMMONS STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE VANCOUVER ART GALLERY Executive Summary We are the Vancouver Art Gallery and we are proud to play a central role in celebrating British Columbian and Canadian artists while also introducing audiences to art and ideas from around the world. The Gallery is in the midst of one of the most exciting endeavours in its long and distinguished history: to create a new, purpose-built museum that will better serve our communities of today and for decades to come. At a time of growth and change for both the institution and the cultural life of this country, we respectfully ask the Government of Canada to join us in the next phase of our journey. This submission outlines how federal funding will help our community support residents, visitors and businesses from across Canada and contribute to the nation’s economic growth. ◊ As the largest public art museum in Western Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has experienced unprecedented growth in the last decade—in its artistic and educational programs as well as in its organizational capacity. The almost tripling of the Gallery’s attendance figures in the last 15 years, a 5-fold increase in membership, the enormous increase in public demand for our many programs, and a 67% increase of the permanent art collection clearly illustrate how our institution has outgrown our building. After more than a decade of research and planning, we are moving forward with our vision to establish an innovative new building for the Gallery.