Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rodney Graham Biography

Rodney Graham Rodney Graham pulls at the threads of cultural and intellectual history through photography, film, music, performance and painting. He presents cyclical narratives that pop with puns and references to literature and philosophy, from Lewis Carroll to Sigmund Freud to Kurt Cobain, with a sense of humour that betrays Graham’s footing in the post-punk scene of late 1970s Vancouver. The nine-minute loop Vexation Island (1997) presents the artist as a 17th-century sailor, lying unconscious under a coconut tree with a bruise on his head; after eight and a half minutes he gets up and shakes the tree inducing a coconut to fall and knock him out, and for the sequence to start again. Graham returns as a cowboy in How I Became a Ramblin’ Man (1999) and as both city dandy and country bumpkin in City Self/Country Self (2001) – fictional characters all engaged in an endless loop of activity. Such dream states and the ramblings of the unconscious are rooted in Graham’s earlier upside-down photographs of oak trees. Inversion, Graham explains, has a logic: ‘You don’t have to delve very deeply into modern physics to realise that the scientific view holds that the world is really not as it appears. Before the brain rights it, the eye sees a tree upside down in the same way it appears on the glass back of the large format field camera I use.’ (2005) Rodney Graham was born in Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada in 1949. He graduated from the University of British Columbia, Burnaby, Canada in 1971 and lives and works in Vancouver, Canada. -

Ffdoespieszak Pieszak CRITICAL REALISM in CONTEMPORARY ART by Alexandra Oliver BFA, Ryerson University, 2005 MA, University of E

CRITICAL REALISM IN CONTEMPORARY ART by Alexandra Oliver BFA, Ryerson University, 2005 MA, University of Essex, 2007 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 FfdoesPieszak Pieszak UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Alexandra Oliver It was defended on April 1, 2014 and approved by Terry Smith, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory, History of Art & Architecture Barbara McCloskey, Associate Professor, History of Art & Architecture Daniel Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago Dissertation Advisor: Josh Ellenbogen, Associate Professor, History of Art & Architecture ii Copyright © by Alexandra Oliver 2014 iii CRITICAL REALISM IN CONTEMPORARY ART Alexandra Oliver, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2014 This study responds to the recent reappearance of realism as a viable, even urgent, critical term in contemporary art. Whereas during the height of postmodern semiotic critique, realism was taboo and documentary could only be deconstructed, today both are surprisingly vital. Nevertheless, recent attempts to recover realism after poststructuralism remain fraught, bound up with older epistemological and metaphysical concepts. This study argues instead for a “critical realism” that is oriented towards problems of ethics, intersubjectivity, and human rights. Rather than conceiving of realism as “fit” or identity between representation and reality, it is treated here as an articulation of difference, otherness and non-identity. This new concept draws on the writings of curator Okwui Enwezor, as well as German critical theory, to analyze the work of three artists: Ian Wallace (b. -

Photography and Cinema

Photography and Cinema David Campany Photography and Cinema EXPOSURES is a series of books on photography designed to explore the rich history of the medium from thematic perspectives. Each title presents a striking collection of approximately80 images and an engaging, accessible text that offers intriguing insights into a specific theme or subject. Series editors: Mark Haworth-Booth and Peter Hamilton Also published Photography and Australia Helen Ennis Photography and Spirit John Harvey Photography and Cinema David Campany reaktion books For Polly Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2008 Copyright © David Campany 2008 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Campany, David Photography and cinema. – (Exposures) 1. Photography – History 2. Motion pictures – History I. Title 770.9 isbn–13: 978 1 86189 351 2 Contents Introduction 7 one Stillness 22 two Paper Cinema 60 three Photography in Film 94 four Art and the Film Still 119 Afterword 146 References 148 Select Bibliography 154 Acknowledgements 156 Photo Acknowledgements 157 Index 158 ‘ . everything starts in the middle . ’ Graham Lee, 1967 Introduction Opening Movement On 11 June 1895 the French Congress of Photographic Societies (Congrès des sociétés photographiques de France) was gathered in Lyon. Photography had been in existence for about sixty years, but cinema was a new inven- tion. -

Marian Penner Bancroft Rca Studies 1965

MARIAN PENNER BANCROFT RCA STUDIES 1965-67 UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, Arts & Science 1967-69 THE VANCOUVER SCHOOL OF ART (Emily Carr University of Art + Design) 1970-71 RYERSON POLYTECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, Toronto, Advanced Graduate Diploma 1989 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, Visual Arts Summer Intensive with Mary Kelly 1990 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, short course with Griselda Pollock SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, upcoming in May 2019 WINDWEAVEWAVE, Burnaby, BC, video installation, upcoming in May 2018 HIGASHIKAWA INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL GALLERY, Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan, Overseas Photography Award exhibition, Aki Kusumoto, curator 2017 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, RADIAL SYSTEMS photos, text and video installation 2014 THE REACH GALLERY & MUSEUM, Abbotsford, BC, By Land & Sea (prospect & refuge) 2013 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HYDROLOGIC: drawing up the clouds, photos, video and soundtape installation 2012 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, SPIRITLANDS t/Here, Grant Arnold, curator 2009 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, CHORUS, photos, video, text, sound 2008 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HUMAN NATURE: Alberta, Friesland, Suffolk, photos, text installation 2001 CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver THE MENDEL GALLERY, Saskatoon SOUTHERN ALBERTA ART GALLERY, Lethbridge, Alberta, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) 2000 GALERIE DE L'UQAM, Montreal, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver, VISIT 1999 PRESENTATION HOUSE GALLERY, North Vancouver, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) UNIVERSITY -

Season 8 Screening Guide-09.09.16

8 ART IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE TO THE EIGHTH SEASON © ART21 2016. All Rights Reserved. art21.org | pbs.org/art21 GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE Through in-depth profiles and interviews, the four- This Screening Guide is designed to help you plan an part series reveals the inspiration, vision, and event using Season Eight of Art in the Twenty-First techniques behind the creative works of some of Century. For each of the four episodes in Season today’s most accomplished contemporary artists. Eight, this guide includes: ART21 travels across the country and abroad to film contemporary artists, from painters and ■ Episode Synopsis photographers to installation and video artists, in ■ Artist Biographies their own spaces and in their own words. The result ■ Screening Resources is a unique opportunity to experience first-hand the Ideas for Screening-Based Events complex artistic process—from inception to finished Screening-Based Activities product—behind today’s most thought-provoking art. Discussion Questions Links to Resources Online Season Eight marks a shift in the award-winning series. For the first time in the show’s history, the Educators’ Guide episodes are not organized around an artistic theme The 62-page color manual ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS includes infomation on artists, such as Fantasy or Fiction. Instead the 16 featured before-viewing, while-viewing, Public screenings of the Art in the Twenty-First artists are grouped according to the cities where and after-viewing discussion Century series illuminate the creative process of questions, as well as classroom they live and work, revealing unique and powerful activities and curriculum today’s visual artists in order to deepen audience’s relationships—artistic and otherwise—to place. -

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol. 44 Issue 97 While the Artery is providing this newsletter as a courtesy service, every effort is made to ensure that information listed below is timely and accurate. However we are unable to guarantee the accuracy of information and functioning of all links. INDEX # ON AT THE GALLERY: Exhibition My Vintage Rubble and Fish & Moose series 1 Mini-retrospective by Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wednesday, Feb 1, 6:30 pm EVENTS AROUND TOWN EVENTS 2-6 EXHIBITIONS 7-24 THEATRE 25/26 WORKSHOPS 27-30 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS LOCAL EXHIBITIONS 31 GRANTS 32 MISCELLANEOUS 33 PUBLIC ART 34 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS NATIONAL AWARDS 35 EXHIBITIONS 36-44 FAIR 45/46 FESTIVAL 47-49 JOB CALL 50-56 CALL FOR PARTICPATION 57 PERFORMANCE 58 CONFERENCE 59 PUBLIC ART 60-63 RESIDENCY 64-69 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS INTERNATIONAL WEBSITE 70 BY COUNTRY ARGENTINA RESIDENCY 71 AUSTRIA PRIZE 72 BRAZIL RESIDENCY 73/74 CANADA RESIDENCY 75-79 FRANCE RESIDENCY 80/81 GERMANY RESIDENCY 82 ICELAND PERFORMERS 83 INDIA RESIDENCY 84 IRELAND FESTIVAL 85 ITALY FAIR 86 RESIDENCY 87-89 MACEDONIA RESIDENCY 90 MEXICO RESIDENCY 91/92 MOROCCO RESIDENCY 93 NORWAY RESIDENCY 94 PANAMA RESIDENCY 95 SPAIN RESIDENCY 96 RETREAT 97 UK RESIDENCY 98/99 USA COMPETITION 100 EXHIBITION 101 FELLOWSHIP 102 RESIDENCY 103-07 BRITANNIA ART GALLERY: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: 108 SUBMISSIONS TO THE ARTERY E-NEWSLETTER 109 VOLUNTEER RECOGNITION 110 GALLERY CONTACT INFORMATION 111 ON AT BRITANNIA ART GALLERY 1 EXHIBITIONS: February 1 - 24 My Vintage Rubble, Fish and Moose series – Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wed. -

Rodney Graham CV

Rodney Graham Lives and works in Vancouver, Canada 1979–80 Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada 1968–71 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 1949 Born in Vancouver, Canada Selected Solo Exhibitions 2020 ‘Artists and Models', Serlachius Museum Gösta, Mänttä, Finland ‘Painting Problems’, Lisson Gallery 2019 303 Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2018 ‘Central Questions of Philosophy’, Lisson Gallery, London, UK 2017 ‘Lightboxes’, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany 303 Gallery, New York, NY, USA ‘That’s Not Me’, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK; Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Netherlands; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland ‘Canadian Impressionist’, Canada House, London, UK ‘Media Studies’, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland 2016 ‘You should be an Artist’, Le Consortium, Dijon, France ‘Waterloo Billboard Commissions’, Hayward Gallery, London, UK ‘Jack of All Trades’, Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art, Toronto, Canada ‘Più Arte dello Scovolino!’, Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy Alt Art Space, Istanbul Turkey 2015 Sammlung Goetz, Munich, Germany ‘Kitchen Magic Drawings’, Galerie Rüdinger Schöttle, Munich, Germany 2014 ‘Rodney Graham: Props and Other Paintings’, Charles H. Scott Gallery, Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Vancouver, Canada ‘Collected Works’, Rennie Collection, Vancouver, Canada ‘Torqued Chandelier Release and Other Works’, Belkin Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 2013 Lisson Gallery, London, UK 303 Gallery, New York, NY, USA ‘The Four Seasons’, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland 2012 ‘Canadian Humourist’, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada Johnen Galerie, Berlin, Germany 2011 Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA ‘Vignettes of Life’, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland ‘Rollenbilder – Rollenspiele’, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, Austria ‘The Voyage or Three Years at Sea: Part 1. -

Mindful Photographer

Operating Manual for the Mindful Photographer Ed Heckerman Copyright © 2017 Cerritos College and Ed Heckerman 11110 Alondra Blvd., Norwalk, CA 90650 Second Edition, 2018 This interactive PDF was made in partial fulfillment for a sabbatical during the academic year 2016 - 2017. No part of the text of this book may be reporduced without permission from Cerritos College. All photographs were taken by Ed Heckerman and produced independently from sabbat- ical contract. Ed Heckerman maintains the copyright for all the photographs and edition changes. No images may be copied from this manual for any use without his consent. Contents Part 1 — Insights and Aspirations 1 contents page Introduction 1 What is Photography? 2 What is a Photograph? Motivations — Why Make Photographs? Photography and Mindfulness 6 Thoughts On Tradition ��������������������������������������������������������������������������12 Part 2 — Navigating Choices ������������������������������������������������������������� 14 Cameras Loading Your Camera Unloading Your Camera Manual Focus Autofocus Sensitivity and Resolution — ISO Controlling Exposure — Setting the Aperture and Shutter Speed Shutter Speed Coordinating Apertures and Shutter Speeds Exposure Metering Systems ��������������������������������������������������������������� 25 Full-frame Average Metering Center Weighted Metering Spot Metering Multi-Zone Metering Incident Metering -

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY a Case for Support

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY A Case for Support A GATHERING PLACE for Transformative Experiences with Art Art is one of the most meaningful ways in which a community expresses itself to the world. Now in its ninth decade as a significant contributor The Gallery’s art presentations, multifaceted public to the vibrant creative life of British Columbia and programs and publication projects will reflect the Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has embarked on diversity and vitality of our community, connecting local a transformative campaign to build an innovative and ideas and stories within the global realm and fostering inspiring new art museum that will greatly enhance the exchanges between cultures. many ways in which citizens and visitors to the city can experience the amazing power of art. Its programs will touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, through remarkable, The new building will be a creative and cultural mind-opening experiences with art, and play a gathering place in the heart of Vancouver, unifying substantial role in heightening Vancouver’s reputation the crossroads of many different neighbourhoods— as a vibrant place in which to live, work and visit. Downtown, Yaletown, Gastown, Chinatown, East Vancouver—and fuelling a lively hub of activity. For many British Columbians, this will be the most important project of their Open to everyone, this will be an urban space where museum-goers and others will crisscross and encounter generation—a model of civic leadership each other daily, and stop to take pleasure in its many when individuals come together to build offerings, including exhibitions celebrating compelling a major new cultural facility for its people art from the past through to artists working today— and for generations of children to come. -

New Year's in Vancouver

NEW YEAR’S IN Activity Level: 1 VANCOUVER December 30, 2021 – 4 Days 1 Dinner Included With Salute to Vienna concert at Orpheum Fares per person: $1,470 double/twin; $1,825 single; $1,420 triple Please add 5% GST. Ring in 2022 in style and enjoy the annual performance of Salute to Vienna presented Early Bookers: $60 discount on first 15 seats; $30 on next 10 by the Vancouver Symphony. It has an Experience Points: outstanding cast of 75 musicians, singers, Earn 32 points on this tour. and dancers, and has been billed as the Redeem 32 points if you book by October 27, 2021. world’s greatest New Year’s concert. We Departure from: Victoria have reserved superb seats in the Centre Orchestra of the Orpheum Theatre. Two other shows are also included, but most theatre companies are still emerging from Covid shutdowns and planning their fall and winter schedules. A morning at the Vancouver Art Gallery is included. The tour stays 3 nights at the renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver. Salute to Vienna ITINERARY Day 1: Thursday, December 30 such as the Gateway or Granville Island Stage. Transportation is provided mid-day to the Again, if you are not interested in attending, you renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver and we stay can opt out and your fare will be reduced. We three nights. Opened in 1939 at a cost of $12 return to the hotel after the show, then at million, it was the third Hotel Vancouver and a midnight you may want to celebrate the arrival of downtown landmark with its copper green roof 2022 in the hotel lounge or nearby. -

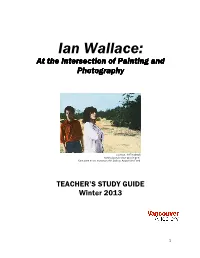

Ian Wallace: at the Intersection of Painting and Photography

Ian Wallace: At the Intersection of Painting and Photography Lookout , 1979 (detail) hand-coloured silver gelatin print Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Acquisition Fund TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE Winter 2013 1 Contents Page Program Information and Goals ................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition...................................................................................................................... 4 Artist Information......................................................................................................................................... 5 Ian Wallace: Essential Terms 101.............................................................................................................. 6 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. Ian Wallace and His Art ................................................................................................................... 7 Artist Information Sheet 1 (intermediate/secondary students) ................................................... 8 Artist Information Sheet 2 (primary students)............................................................................... 9 Student Worksheet........................................................................................................................10 2. History Paintings Now....................................................................................................................11 3. Heroes in the Street.......................................................................................................................13