Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A European Cooperation Programme

Year 32 • Issue #363 • July/August 2019 2,10 € ESPAÑOLA DE InternationalFirst Edition Defence of the REVISTA DEFEandNS SecurityFEINDEF ExhibitionA Future air combat system A EUROPEAN COOPERATION PROGRAMME BALTOPS 2019 Spain takes part with three vessels and a landing force in NATO’s biggest annual manoeuvres in the Baltic Sea ESPAÑOLA REVISTA DE DEFENSA We talk about defense NOW ALSO IN ENGLISH MANCHETA-INGLÉS-353 16/7/19 08:33 Página 1 CONTENTS Managing Editor: Yolanda Rodríguez Vidales. Editor in Chief: Víctor Hernández Martínez. Heads of section. Internacional: Rosa Ruiz Fernández. Director de Arte: Rafael Navarro. Parlamento y Opinión: Santiago Fernández del Vado. Cultura: Esther P. Martínez. Fotografía: Pepe Díaz. Sections. Nacional: Elena Tarilonte. Fuerzas Armadas: José Luis Expósito Montero. Fotografía y Archivo: Hélène Gicquel Pasquier. Maque- tación: Eduardo Fernández Salvador. Collaborators: Juan Pons. Fotografías: Air- bus, Armada, Dassault Aviation, Joaquín Garat, Iñaki Gómez, Latvian Army, Latvian Ministry of Defence, NASA, Ricardo Pérez, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGY Jesús de los Reyes y US Navy. Translators: Grainne Mary Gahan, Manuel Gómez Pumares, María Sarandeses Fernández-Santa Eulalia y NGWS, Fuensanta Zaballa Gómez. a European cooperation project Germany, France and Spain join together to build the future 6 fighter aircraft. Published by: Ministerio de Defensa. Editing: C/ San Nicolás, 11. 28013 MADRID. Phone Numbers: 91 516 04 31/19 (dirección), 91 516 04 17/91 516 04 21 (redacción). Fax: 91 516 04 18. Correo electrónico:[email protected] def.es. Website: www.defensa.gob.es. Admi- ARMED FORCES nistration, distribution and subscriptions: Subdirección General de Publicaciones y 16 High-readiness Patrimonio Cultural: C/ Camino de Ingenieros, 6. -

Soak up Every Last Drop of Summer in Ohio Plan Your End-Of-Summer Ohio Road Trip with Ohio

For Immediate Release Contact: Tamara Brown, 614-466-8591, [email protected] Soak Up Every Last Drop of Summer in Ohio Plan your end-of-summer Ohio Road Trip with Ohio. Find It Here. COLUMBUS, Ohio (August 1, 2019) – As August kicks-off, it’s time to make the most of those remaining summer days before school schedules begin. With so much to do in Ohio, you don’t have to go far to find breathtaking waterfront views, live music or an inspiring museum. The only question is, where to first? “There is still time to take an Ohio. Find It Here. road trip,” said Matt MacLaren, director of TourismOhio. “It’s the perfect time to plan a road trip around big anniversary celebrations including The Shawshank Redemption or continue to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Ohioan Neil Armstrong’s first step on the moon.” At RoadTrips.Ohio.org you’ll find 10 themed road trip routes complete with Spotify playlists curated by the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Here are some of the big anniversaries offering plenty of end-of- summer opportunities to enjoy with those who mean the most to you. Anniversary Celebrations The Shawshank Redemption 25th Anniversary Celebration, Mansfield (August 16 – 28) Get busy living with a screening of The Shawshank Redemption in the Renaissance Theatre, where Shawshank originally premiered in 1994. As part of this special anniversary event, attendees will be able to meet some of the film’s celebrities at the Ohio State Reformatory, and the annual Shawshank Hustle 7K route will take runners past several of the film’s locations. -

1-Bureaud Annotated

A New territory of (In)human Proportions Annick Bureaud introduction to the space art special section, Art Press, n°298, February 2004 Where is space? For the ancients, it was simple. There was the Earth and the Heavens, and the more or less divine links between the two. Science secularized the cosmos, and engineers hurled their rockets right into it. Where does space begin? Where does the Earth end? On its surface? With its atmosphere? With its gravitational field? With what used to be called “the known world,” that is, the “inhabited” and mapped world ? French uses the vague term espace to designate “the world beyond the world,” while English prefers “outer space,” implying that there is an “inside space” as well. Space and territories are at the core of many space artworks. Leave the Earth, turn around and look back at it. This macroscopic vision involves a shift in the relationship of scale between us and our planet that is simultaneously glorious and overwhelming. Alain Jacquet took up this global vision in his serigraph First Breakfast (1972), where the Earth, seen from the pole, looks like an image seen on a radar screen. The human vision and the artificial vision of satellites for a new re- presentation of the world. For the @ Geosphere Project (1990), Tom Van Sant made a polar projection map of the earth using satellite photos. This “real” image goes beyond cartographic abstraction, with its political boundaries etc. It is unreal, or perhaps ultra- real, because there is not a cloud in sight. But you can also use the Earth as a medium, as if going beyond Land Art, and draw on it an eye that is reflected by the "eye" of the satellites in an endlessly reflexive stare (Reflections from Earth, Tom Van Sant, 1980), or its medieval symbol, fusing sign and object (Signature Terre, Pierre Comte, 1989). -

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, NY Académie Julian, Paris, France

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, NY Académie Julian, Paris, France Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, France Black Mountain College, Asheville, North Carolina Art Students League of New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Now, Then and Always, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY (forthcoming) JDJ | The Ice House, Garrison, NY 2020 Art Hysteri of Susan Weil: 70 Years of Innovation and Wit, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY [online exhibition] 2019 Once In A Blue Moon, Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich, Germany 2017 Susan Weil: Now and Then, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Susan Weil’s James Joyce: Shut Your Eyes and See, University at Buffalo, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, Buffalo, NY 2015 Poemumbles: 30 Years of Susan Weil’s Poem | Images, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, NC 2013 Time’s Pace: Recent Works by Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Reflections, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2008-2009 Motion Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA (2008); Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Hong Kong (2009) Trees, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Now & Then: A Retrospective of Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Ear’s Eye for James Joyce, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Moving Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Aronowitsch, Stockholm, Sweden 2000 Wanås, Knislinge, Sweden 1998 North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND Susan Weil: Full Circle, Black Mountain Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, -

Looking for Love: Identifying Robert Rauschenberg's Collage Elements in a Lost, Early Work

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Greg Allen, “Looking for Love: Identifying Robert Rauschenberg’s Collage Elements in a Lost, Early Work,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1663. Looking for Love: Identifying Robert Rauschenberg’s Collage Elements in a Lost, Early Work Greg Allen, artist In 2012, while considering questions of loss, the archive, and the digitization of everything, I decided to conduct an experiment by remaking paintings that had been destroyed and were otherwise known only from old photographs. What is the experience of seeing this object IRL, I wondered, instead of as a photograph, a negative, or a JPEG? The impetus for this project was a cache of photographs of paintings Gerhard Richter destroyed in the 1960s. I soon turned to a destroyed painting I have thought about and wanted to see for a long time: one of the earliest known works by Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Should Love Come First? (c. 1951; fig. 1).1 Like Rauschenberg’s later Combines, Should Love Come First? was a composition of paint and collage on canvas. Remaking it meant identifying the collage elements from the lone photograph of the work; so far it has taken five years. Fig. 1. Robert Rauschenberg, Should Love Come First? 1951. Oil, printed paper, and graphite on canvas, 24 1/4 x 30 in., original state photographed by Aaron Siskind for the Betty Parsons Gallery. No longer extant. Repainted by the artist in 1953; now k nown as Untitled (Small Black Painting), (1953; Kunstmuseum Basel), image courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York journalpanorama.org • [email protected] • ahaaonline.org Allen, “Looking for Love” Page 2 This endeavor was predicted and mocked by eminent scholars in equal parts. -

Season 2, Ep. 9 Walking on the Moon Pt. 2 FINAL.Pdf

AirSpace Season 2, Episode 9 Walking on the Moon Part 2 Nick: Hi and welcome to AirSpace. This is part two of our special Apollo At 50 series. Emily: In our last episode we talked about the science that astronauts, Nick Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin conducted on the moon. This episode, we want to talk about the lunar science Apollo astronauts enabled back on Earth. Nick: With 842 pounds of moon rocks transported back to Earth, we've had a lot to study over the last 50 years. Matt: And only some of those rocks were studied back 50 years ago. NASA scientists made a plan to keep a large portion of the lunar samples sealed off and totally pristine for the last 50 years until now. Nick: Today, we'll hear from space scientists who are unsealing those samples for the first time this summer. Emily: The most exciting thing to me is that we can look at these samples with techniques that weren't even developed or even maybe thought of when the Apollo samples first came back to the Earth. Matt: And we'll talk with one lunar geologist who was working on a proposal to go back to the moon with a rover. It could dive deeper into lunar mysteries than ever before. Emily: Usually when we're studying these materials, we can use satellite data but that's only showing us the top microns to upper meter or so of the surface. With this we're really peering in. This hole is a hundred meters deep. -

Perpetual Inventory Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

Perpetual Inventory Author(s): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol. 88 (Spring, 1999), pp. 86-116 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/779226 . Accessed: 01/05/2013 15:51 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Wed, 1 May 2013 15:51:29 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PerpetualInventory* ROSALINDKRAUSS I wentin for myinterview for thisfantastic job. ... Thejob had a greatname-I might use itfor a painting-"PerpetualInventory." -Rauschenberg to Barbara Rose 1. Here are threedisconcerting remarks and one document: The firstsettles out from a discussion of the various strategies Robert Rauschenbergfound to defamiliarizeperception, so that, in Brian O'Doherty's terms,"the citydweller's rapid scan" would now displace old habits of seeing and "the art audience's stare" would yield to "the vernacularglance."I With its vora- ciousness,its lack of discrimination,its wanderingattention, -

Apollo 17 - Proof It Was Kubricked

Apollo 17 - Proof it was Kubricked Please read all of the text before reviewing the photos. This text provides additional information that you probably will not otherwise notice when reviewing the photos. If there is material that others have also discovered, so be it. My research was done using a white room approach. Unless stated otherwise, all ideas, discoveries and facts presented are my own work. It would be appreciated if my inbox is not stuffed with “I found it or so-and-so found it first” nonsense. I will respond to all sensible emails. I need to admit here that my goal in reviewing Moon walk and rover photos from Apollo 17 was to find possible artifacts. When I found one particular image after many hours of reviewing photos, my research work came to a complete stop. After reviewing hundreds of Apollo 17 images, I found conclusive proof a stage was definitely used for most, if not all of the Moon surface photos. The entire world has been “Kubricked” for decades. Others in recent years found through image processing that the black sky in Moon walk images is actually a painted backdrop. We shall see that image processing is not even needed to see this. Over and over in photos taken on the surface of the Moon I continued to find the same irregularities. Keep in mind all these photos were supposedly taken by astronauts who trained and practiced for weeks (their own words) to use a high quality Hasselblad camera. This camera is completely manual, and requires the astronaut to set the distance to the lens (in feet) before taking each picture. -

Susan Weil Once in a Blue Moon Jun 06 – Aug 31, 2019 Opening: Jun 05, 7 – 9 Pm

Susan Weil Once In A Blue Moon Jun 06 – Aug 31, 2019 Opening: Jun 05, 7 – 9 pm Susan Weil, Wandering Chairs, 1998, silver gelatin print, 113 x 302 cm. © S. Weil and C. Rauschenberg This exhibition marks the first time the US painter Susan Weil, b. 1930, presents her work at Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle. The artist studied at Black Mountain College under Josef Albers, together with Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly. Despite her abstract expressionist style, the artist, unlike her male counterparts, never let herself be influenced by the prevailing tendencies of the time. An important member of the New York School of Art, Susan Weil refuses to be categorized in any one style, and despite being influenced by abstract expressionism, she never completely forgot about the power of the figurative. The exhibition Once In A Blue Moon comprises seminal works from 1989 to the present. Taking familiar objects as a starting point, Susan Weil reduces all elements to their intrinsic nature to then reconstruct them in unexpected ensembles. Her work Wandering Chairs, a cooperation with her son Christopher Rauschenberg, consists of two chairs and the artist’s portrait, assembled like a puzzle from our different pieces. The viewer’s searching eye is first captured by the entire picture full of movement and disruption. Gradually, one is willing to engage in the artist’s game, constructing with her a new world in which the objects find each other in unanticipated ways. The composition of her works is always poetic, dynamic, and playful; it often seems as though the works dance on the walls. -

Susan Weil Press Release

JDJ Susan Weil February 27 - April 17, 2021 Over the course of her seventy year career, Susan Weil’s exuberant practice has drawn inspiration from nature, literature, art history, and her own lived experience. Weil came of age as an artist in the postwar period, studying under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College with Willem & Elaine de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg & Cy Twombly. Although she has deep roots in the New York School of Art, her work defes easy categorization. Central to Weil’s practice is her fascination with expressing time through motion, which she does in a number of ways, including her use of seriality, collage, and kinetic sculptural elements. She often works with blueprints, exposing the paper to light and using her body and other objects to make impressions, a technique that she introduced to her then-partner Robert Rauschenberg in 1949 and that she continues to use today. Weil’s oeuvre oscillates between the abstract and the concrete, and this exhibition brings together four bodies of work from the 1970s through the 1990s that reference the female body. Regardless of form or medium, there is a sense of vivacity, dynamism, and playfulness present in Weil’s work. One can sense the pleasure she fnds in everyday life—her delight in experiencing the passing of time as she moves through the world with a great sense of curiosity. The spray paint works on paper, exhibited here for the frst time in ffty years, express the fgure in a simple and contained way. Weil made these pieces in a free-fowing process, working on several at a time and allowing the compositions to come to her spontaneously. -

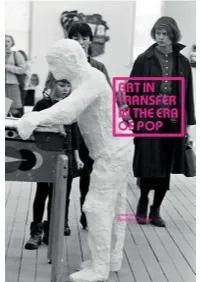

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Gagosian Gallery

Slate.com November 11, 2010 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Robert Rauschenberg was the epic artist of the Postmodern era, splashing in every medium and style, sometimes all at once—a trait on clear view in his first major show since his death in 2008, put on by his estate at Gagosian Gallery's West 21stStreet branch in New York City. Rauschenberg came to New York in 1949, at age 24, as the Abstract Expressionists were on the rise, and though he emulated their brash brushstrokes and dynamic use of color, he rejected their grimness, their sense of art as an isolated struggle. Art, he thought, was serious, but it was also playful, and a way of merging himself with everything around him. He once said, "Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)" The critic Leo Steinberg, who saw Rauschenberg as the most inventive painter since Picasso, wrote, "What he invented above all was … a pictorial surface that let the world in again." Caryatid Cavalcade II/ROCI Chile, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 138½ x 260¾ inches. © Estate of Robert Rauschenberg/Licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y./DACS, London. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Robert McKeever. Rauschenberg's most boisterous, original works were the "combines"—painting- sculpture combinations splattered not only with streaks and drips of color but also with familiar objects: scraps of fabric, strips of wood, a necktie, newspaper clippings, a Coke bottle, metal signs, a zipper. Rauschenberg would walk around his block in Lower Manhattan and pick up street trash that he found interesting, then take it back to his studio and fit it into his art.