Perpetual Inventory Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017

The Museum of Modern Art Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017 Stop List 800. Introduction 801. Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, Double Rauschenberg, c. 1950 802. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Black Painting with Asheville Citizen), c. 1952 8021. Underneath Asheville Citizen 803. Robert Rauschenberg, White Painting, 1951, remade 1960s 804. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Scatole personali) (Personal boxes), 1952-53 805. Robert Rauschenberg with John Cage, Automobile Tire Print, 1953 806. Robert Rauschenberg with Willem de Kooning and Jasper Johns, Erased de Kooning, 1953 807. Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955 8071. Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines 808. Robert Rauschenberg, Minutiae, 1954 809. Robert Rauschenberg, Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante's Inferno, 1958-60 810. Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959 811. Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-59 812. Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960 813. Robert Rauschenberg, Trophy IV (for John Cage), 1961 814. Robert Rauschenberg, Homage to David Tudor (performance), 1961 815. Robert Rauschenberg, Pelican, (performance), 1963 USA20415F – MoMA – Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Script 1 816. Robert Rauschenberg, Retroactive I, 1965 817. Robert Rauschenberg, Oracle, 1962-65 818. Robert Rauschenberg with Carl Adams, George Carr, Lewis Ellmore, Frank LaHaye, and Jim Wilkinson, Mud Muse, 1968-71 819. John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol with Fred Waldhauer, The Moon Museum, 1969 820. Robert Rauschenberg, 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, 1966 (Poster, ephemera) 821. Robert Rauschenberg, Cardboards, 1971-1972 822. Robert Rauschenberg, Jammers (series), 1974-1976 823. Robert Rauschenberg, Glut (series), 1986-97 824. Robert Rauschenberg, Glacial Decoy (series of 620 slides and film), 1979 825. -

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, NY Académie Julian, Paris, France

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, NY Académie Julian, Paris, France Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, France Black Mountain College, Asheville, North Carolina Art Students League of New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Now, Then and Always, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY (forthcoming) JDJ | The Ice House, Garrison, NY 2020 Art Hysteri of Susan Weil: 70 Years of Innovation and Wit, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY [online exhibition] 2019 Once In A Blue Moon, Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich, Germany 2017 Susan Weil: Now and Then, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Susan Weil’s James Joyce: Shut Your Eyes and See, University at Buffalo, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, Buffalo, NY 2015 Poemumbles: 30 Years of Susan Weil’s Poem | Images, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, NC 2013 Time’s Pace: Recent Works by Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Reflections, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2008-2009 Motion Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA (2008); Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Hong Kong (2009) Trees, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Now & Then: A Retrospective of Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Ear’s Eye for James Joyce, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Moving Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Aronowitsch, Stockholm, Sweden 2000 Wanås, Knislinge, Sweden 1998 North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND Susan Weil: Full Circle, Black Mountain Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, -

Looking for Love: Identifying Robert Rauschenberg's Collage Elements in a Lost, Early Work

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Greg Allen, “Looking for Love: Identifying Robert Rauschenberg’s Collage Elements in a Lost, Early Work,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1663. Looking for Love: Identifying Robert Rauschenberg’s Collage Elements in a Lost, Early Work Greg Allen, artist In 2012, while considering questions of loss, the archive, and the digitization of everything, I decided to conduct an experiment by remaking paintings that had been destroyed and were otherwise known only from old photographs. What is the experience of seeing this object IRL, I wondered, instead of as a photograph, a negative, or a JPEG? The impetus for this project was a cache of photographs of paintings Gerhard Richter destroyed in the 1960s. I soon turned to a destroyed painting I have thought about and wanted to see for a long time: one of the earliest known works by Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), Should Love Come First? (c. 1951; fig. 1).1 Like Rauschenberg’s later Combines, Should Love Come First? was a composition of paint and collage on canvas. Remaking it meant identifying the collage elements from the lone photograph of the work; so far it has taken five years. Fig. 1. Robert Rauschenberg, Should Love Come First? 1951. Oil, printed paper, and graphite on canvas, 24 1/4 x 30 in., original state photographed by Aaron Siskind for the Betty Parsons Gallery. No longer extant. Repainted by the artist in 1953; now k nown as Untitled (Small Black Painting), (1953; Kunstmuseum Basel), image courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York journalpanorama.org • [email protected] • ahaaonline.org Allen, “Looking for Love” Page 2 This endeavor was predicted and mocked by eminent scholars in equal parts. -

Susan Weil Once in a Blue Moon Jun 06 – Aug 31, 2019 Opening: Jun 05, 7 – 9 Pm

Susan Weil Once In A Blue Moon Jun 06 – Aug 31, 2019 Opening: Jun 05, 7 – 9 pm Susan Weil, Wandering Chairs, 1998, silver gelatin print, 113 x 302 cm. © S. Weil and C. Rauschenberg This exhibition marks the first time the US painter Susan Weil, b. 1930, presents her work at Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle. The artist studied at Black Mountain College under Josef Albers, together with Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly. Despite her abstract expressionist style, the artist, unlike her male counterparts, never let herself be influenced by the prevailing tendencies of the time. An important member of the New York School of Art, Susan Weil refuses to be categorized in any one style, and despite being influenced by abstract expressionism, she never completely forgot about the power of the figurative. The exhibition Once In A Blue Moon comprises seminal works from 1989 to the present. Taking familiar objects as a starting point, Susan Weil reduces all elements to their intrinsic nature to then reconstruct them in unexpected ensembles. Her work Wandering Chairs, a cooperation with her son Christopher Rauschenberg, consists of two chairs and the artist’s portrait, assembled like a puzzle from our different pieces. The viewer’s searching eye is first captured by the entire picture full of movement and disruption. Gradually, one is willing to engage in the artist’s game, constructing with her a new world in which the objects find each other in unanticipated ways. The composition of her works is always poetic, dynamic, and playful; it often seems as though the works dance on the walls. -

Susan Weil Press Release

JDJ Susan Weil February 27 - April 17, 2021 Over the course of her seventy year career, Susan Weil’s exuberant practice has drawn inspiration from nature, literature, art history, and her own lived experience. Weil came of age as an artist in the postwar period, studying under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College with Willem & Elaine de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg & Cy Twombly. Although she has deep roots in the New York School of Art, her work defes easy categorization. Central to Weil’s practice is her fascination with expressing time through motion, which she does in a number of ways, including her use of seriality, collage, and kinetic sculptural elements. She often works with blueprints, exposing the paper to light and using her body and other objects to make impressions, a technique that she introduced to her then-partner Robert Rauschenberg in 1949 and that she continues to use today. Weil’s oeuvre oscillates between the abstract and the concrete, and this exhibition brings together four bodies of work from the 1970s through the 1990s that reference the female body. Regardless of form or medium, there is a sense of vivacity, dynamism, and playfulness present in Weil’s work. One can sense the pleasure she fnds in everyday life—her delight in experiencing the passing of time as she moves through the world with a great sense of curiosity. The spray paint works on paper, exhibited here for the frst time in ffty years, express the fgure in a simple and contained way. Weil made these pieces in a free-fowing process, working on several at a time and allowing the compositions to come to her spontaneously. -

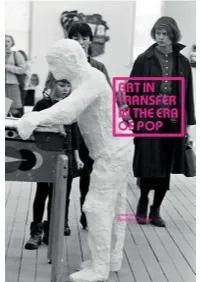

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Gagosian Gallery

Slate.com November 11, 2010 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Robert Rauschenberg was the epic artist of the Postmodern era, splashing in every medium and style, sometimes all at once—a trait on clear view in his first major show since his death in 2008, put on by his estate at Gagosian Gallery's West 21stStreet branch in New York City. Rauschenberg came to New York in 1949, at age 24, as the Abstract Expressionists were on the rise, and though he emulated their brash brushstrokes and dynamic use of color, he rejected their grimness, their sense of art as an isolated struggle. Art, he thought, was serious, but it was also playful, and a way of merging himself with everything around him. He once said, "Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)" The critic Leo Steinberg, who saw Rauschenberg as the most inventive painter since Picasso, wrote, "What he invented above all was … a pictorial surface that let the world in again." Caryatid Cavalcade II/ROCI Chile, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 138½ x 260¾ inches. © Estate of Robert Rauschenberg/Licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y./DACS, London. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Robert McKeever. Rauschenberg's most boisterous, original works were the "combines"—painting- sculpture combinations splattered not only with streaks and drips of color but also with familiar objects: scraps of fabric, strips of wood, a necktie, newspaper clippings, a Coke bottle, metal signs, a zipper. Rauschenberg would walk around his block in Lower Manhattan and pick up street trash that he found interesting, then take it back to his studio and fit it into his art. -

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, New York Académie Julian, Paris

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, New York Académie Julian, Paris, France Black Mountain College, Asheville, North Carolina Arts Students League, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Art Hysteri of Susan Weil: 70 Years of Innovation and Wit, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY [online exhibition] 2019 Once In A Blue Moon, Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich, Germany 2017 Susan Weil: Now and Then, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Susan Weil’s James Joyce: Shut Your Eyes and See, University at Buffalo, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, Buffalo, NY 2015 Poemumbles: 30 Years of Susan Weil’s Poem | Images, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, NC 2013 Time’s Pace: Recent Works by Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Reflections, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2008-2009 Motion Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA (2008); Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Hong Kong (2009) Trees, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Now & Then: A Retrospective of Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Ear’s Eye for James Joyce, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Moving Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Aronowitsch, Stockholm, Sweden 2000 Wanås, Knislinge, Sweden 1998 North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND Susan Weil: Full Circle, Black Mountain Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, NC 1997 National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden Grafikens Hus, Södertälje, Sweden Anders Tornberg Gallery, Lund, Sweden 1996 Galerie Simone Gogniat, Basel, Switzerland -

Robert Rauschenberg Biography

ARTIST BROCHURE Decorate Your Life™ ArtRev.com Robert Rauschenberg Rauschenberg was born October 22, 1925 as Milton Ernst Rauschenberg (he changed his first name as an adult) in Port Arthur, Texas, the son of Dora and Ernest Rauschenberg. His father was of German and Cherokee ancestry and his mother of Anglo-Saxon descent. His parents were Fundamentalist Christians. Rauschenberg studied at the Kansas City Art Institute and the Académie Julian in Paris, France, where he met the painter Susan Weil, who in the summer of 1950 became his wife. In 1948 Rauschenberg and Weil decided to attend Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Josef Albers originally of the Bauhaus school became Rauschenberg's painting instructor at Black Mountain. Albers' preliminary courses relied on strict discipline that did not allow for any "uninfluenced experimentation". Rauschenberg described Albers as influencing him to do "exactly the reverse" of what he was being taught. From 1949 to 1952 Rauschenberg studied with Vaclav Vytlacil and Morris Kantor at the Art Students League of New York, where he met fellow artists Knox Martin and Cy Twombly. Rauschenberg married the painter Susan Weil in 1950. Their only child, Christopher, was born July 16, 1951. They divorced in 1953. According to a 1987 oral history by the composer Morton Feldman, after the end of his marriage, Rauschenberg had romantic relationships with fellow artists Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns. An article by scholar Jonathan D. Katz states that Rauschenberg's affair with Twombly began during his marriage to Susan Weil. Rauschenberg died on May 12, 2008 of heart failure after his personal decision to go off life support, on Captiva Island in Florida. -

Winter 2015–16

THE MAGAZINE OF THEnew INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART/BOSTON WINTER 2015–16 “Extraordinary.” IN THIS ISSUE —New York Times 5 6 2 Meet Ruth eRickson The ICA Assistant Curator talks the BiRthday “Genius abounds.” BRinging Robert Rauschenberg, Mark Dion, PaRty —Boston Globe Black Mountain and guilty pleasures. Artists Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni college to life Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian Jill Medvedow, Ellen Matilda Poss bring their madcap way of life and Director, on opening avenues. art to the ICA. Plus: 7 ways we’re “learning by doing” “The biggest show the ICA has during Leap Before You Look. ever mounted… You should visit.” —New Yorker “A midcentury cultural Camelot.” —Wall Street Journal diane siMPson now on the new The Chicago-based artist creates icaBoston.oRg highly stylized sculptures inspired MeMBeR sPotlight + • Life at Black Mountain by items of clothing from Amish annual donoRs College slideshow bonnets to samurai armor to George Fifield reflects on 25 years of ICA • Tour of Black Mountain everyday apparel. + COMING membership. Mentioned: Krzysztof Wodiczko, College–related attractions SOON: Walid Raad. Bill Viola, Chris Burden, Tara Donovan, and near Boston the days when the Back Bay was cheap. 8 • Exhibitions through 2017 10 • Holiday gift inspiration! PERFORMANCE + PROGRAMS WINTER 2015–16 can we PRogRaM guide Be fRiends? Concerts, dance, film, talks, family programs, Like us on Facebook: facebook.com/ICA.Boston member events, and more this winter. Follow us on Twitter: @ICAinBoston Follow us on Instagram: @ICABoston Cover: Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Changeling at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston. Major support is provided by The Andrew W. -

Download Full Transcript

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG ORAL HISTORY PROJECT The Reminiscences of Agnes Gund Columbia Center for Oral History Research Columbia University 2015 PREFACE The following oral history is the result of a recorded interview with Agnes Gund conducted by Sara Sinclair on April 8, 2015. This interview is part of the Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. The reader is asked to bear in mind that s/he is reading a transcript of the spoken word, rather than written prose. Transcription: Audio Transcription Center Session #1 Interviewee: Agnes Gund Location: New York, New York Interviewer: Sara Sinclair Date: April 8, 2015 Q: Today is April the 8, 2015. This is Sara Sinclair with Agnes Gund and we are in New York. Thank you for making the time to meet with me today. With these oral history interviews, we like to start with a little bit about you, before you intersect with Bob [Rauschenberg]. If we could begin with you telling me a little bit about your early life, maybe sharing some of your early memories of growing up in Cleveland. Gund: Okay. I’d love to. I grew up in a family with six children born in seven years, so we were all about a year apart. We lived outside of Cleveland. My father was a workaholic, a banker. My mother really loved having the children, but she became ill with cancer two years after the last of us was born, my sister, Louise [Gund]. She was in and out of the hospital and sick for eight years. She was supposed to die in six months—or, she was given six months to live. -

London Exhibition Roundup

Buck, Louisa. “London exhibition roundup: a glut of Rauschenberg treats at Tate, the aftermath of Post-Modernism, a De Chirico-inspired group show and Thuring’s trompe l’oeil tapestries,” The Art Newspaper Online. 12 December 2016 London exhibition roundup: a glut of Rauschenberg treats at Tate, the aftermath of Post-Modernism, a De Chirico-inspired group show and Thuring’s trompe l’oeil tapestries by LOUISA BUCK | 12 December 2016 Robert Rauschenberg's Untitled (Spread) (1983) (Image: © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York) Revolt of the Sage, Blain Southern (until 21 January) This ambitious, disquietingly atmospheric show takes its title from a 1916 work by Georgio De Chirico. The picture itself is deliberately absent, but the Italian painter’s moody notion of a mysterious metaphysical realm, redolent of loss and longing and in which “the past is the same as the future…” permeates a diverse lineup of leading contemporary artists. These include Goshka Macuga, Christian Marclay and John Stezaker, which here are made to spark-up unexpected conversations with more historical post-war works by Lynn Chadwick, Jannis Kounellis and Sigmar Polke. Installation view of Revolt of the Sage (2016) (Courtesy of the artists and Blain|Southern. Photo: Peter Mallet) While none of the above—or any of the show’s artists—are Surrealist per se, the collective subconscious is given a thorough prodding as, in multifarious ways, images are fragmented, reframed and/or distorted. In Stezaker’s haunting collages the face from a vintage photographic portrait is replaced by a landscape, or film stills made to merge into and out of their settings; while Sigmar Polke’s prints violently smear found newspaper images.