Looking for Love: Identifying Robert Rauschenberg's Collage Elements in a Lost, Early Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017

The Museum of Modern Art Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017 Stop List 800. Introduction 801. Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, Double Rauschenberg, c. 1950 802. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Black Painting with Asheville Citizen), c. 1952 8021. Underneath Asheville Citizen 803. Robert Rauschenberg, White Painting, 1951, remade 1960s 804. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Scatole personali) (Personal boxes), 1952-53 805. Robert Rauschenberg with John Cage, Automobile Tire Print, 1953 806. Robert Rauschenberg with Willem de Kooning and Jasper Johns, Erased de Kooning, 1953 807. Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955 8071. Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines 808. Robert Rauschenberg, Minutiae, 1954 809. Robert Rauschenberg, Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante's Inferno, 1958-60 810. Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959 811. Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-59 812. Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960 813. Robert Rauschenberg, Trophy IV (for John Cage), 1961 814. Robert Rauschenberg, Homage to David Tudor (performance), 1961 815. Robert Rauschenberg, Pelican, (performance), 1963 USA20415F – MoMA – Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Script 1 816. Robert Rauschenberg, Retroactive I, 1965 817. Robert Rauschenberg, Oracle, 1962-65 818. Robert Rauschenberg with Carl Adams, George Carr, Lewis Ellmore, Frank LaHaye, and Jim Wilkinson, Mud Muse, 1968-71 819. John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol with Fred Waldhauer, The Moon Museum, 1969 820. Robert Rauschenberg, 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, 1966 (Poster, ephemera) 821. Robert Rauschenberg, Cardboards, 1971-1972 822. Robert Rauschenberg, Jammers (series), 1974-1976 823. Robert Rauschenberg, Glut (series), 1986-97 824. Robert Rauschenberg, Glacial Decoy (series of 620 slides and film), 1979 825. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1992.Pdf

N A N A L E ENT S NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR~THE ARTS 1992, ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR!y’THE ARTS The Federal agency that supports the Dear Mr. President: visual, literary and pe~orming arts to I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report benefit all A mericans of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year ended September 30, 1992. Respectfully, Arts in Education Challenge &Advancement Dance Aria M. Steele Design Arts Acting Senior Deputy Chairman Expansion Arts Folk Arts International Literature The President Local Arts Agencies The White House Media Arts Washington, D.C. Museum Music April 1993 Opera-Musical Theater Presenting & Commissioning State & Regional Theater Visual Arts The Nancy Hanks Center 1100 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington. DC 20506 202/682-5400 6 The Arts Endowment in Brief The National Council on the Arts PROGRAMS 14 Dance 32 Design Arts 44 Expansion Arts 68 Folk Arts 82 Literature 96 Media Arts II2. Museum I46 Music I94 Opera-Musical Theater ZlO Presenting & Commissioning Theater zSZ Visual Arts ~en~ PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP z96 Arts in Education 308 Local Arts Agencies State & Regional 3z4 Underserved Communities Set-Aside POLICY, PLANNING, RESEARCH & BUDGET 338 International 346 Arts Administration Fallows 348 Research 35o Special Constituencies OVERVIEW PANELS AND FINANCIAL SUMMARIES 354 1992 Overview Panels 360 Financial Summary 36I Histos~f Authorizations and 366~redi~ At the "Parabolic Bench" outside a South Bronx school, a child discovers aspects of sound -- for instance, that it can be stopped with the wave of a hand. Sonic architects Bill & Mary Buchen designed this "Sound Playground" with help from the Design Arts Program in the form of one of the 4,141 grants that the Arts Endowment awarded in FY 1992. -

2019 Annual Report

2019 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friends, This has been another year of unparalleled exhibitions and performances, a celebration of what’s possible in our new home and with the support of our community. At the beginning of 2019, we were in the last few weeks of the inaugural exhibition at 120 College Street, Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence and Black Mountain College, which was a major accomplishment in its scope and its expansion of community partnerships. Next, we presented an intimate look at the school’s political dimensions, both internal and external, through the exhibition Politics at Black Mountain College. During the same time period, the exhibition Aaron Siskind: A Painter’s Photographer and Works on Paper by BMC Artists revealed the photographer’s elegant approach to abstraction alongside works by others in his circle of influence. From June through August, our galleries filled with sound as part of Materials, Sounds + Black Mountain College, an exploration of contemporary experimental and material-based processes rooted in theories and practices developed at Black Mountain College. We closed out the year with VanDerBeek + VanDerBeek, an exhibition that bridges the historic and contemporary through an intergenerational artistic conversation. 2019 also marked the 100th birthday of Merce Cunningham, and 100 years since the founding of the Bauhaus, which closed in the same year Black Mountain College opened, seeding the latter with its faculty and utopian values. Both centennials sparked global celebrations, transcending geographic and disciplinary boundaries to honor the impact of courageous communities and collaborators. Image credit: Come Hear NC (NCDNCR) | Ken Fitch We joined the world in these celebrations through a special installation of historic dance films of the Cunningham Dance Company at this year’s {Re}HAPPENING, the exhibition BAUHAUS 100, and a virtual reality exploration of the Bauhaus Dessau building, on loan from the Goethe- Institut. -

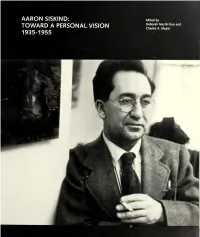

AARON SISKIND: Edited by a VISION Deborah Martin Kao and TOWARD PERSONAL Charles A

AARON SISKIND: Edited by A VISION Deborah Martin Kao and TOWARD PERSONAL Charles A. Meyer 1935-1955 Cover photograph: Morris Engel Portrait of Aaron Siskind (ca 1947) National Portrait Gallery/ Smithsonian Institution AARON SISKIND: Edited by TOWARD A PERSONAL VISION Deborah Martin Kao and Charles A. Meyer 1935-1955 Boston College Museum of Ar Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts AARON SISKIND: TOWARD A PERSONAL VISION "The Feature Group" by Aaron Siskind from Photo Richard Nickel’s photographs from the Aaron Siskind and 1935-1955. Notes. June-July 1940 Repnnted in Nathan Lyons, Students' Louis Sullivan Project. Institute of Design. editor. Photo Notes (facsimile). A Visual Studies Repnnt Chicago, ca 1956, in the collection of Len Gittieman. Copyright © 1994 by Boston College Museum of Art, Book (Rochester: Visual Studies Workshop, 1977). Reprinted by permission of the Richard Nickel Committee. Deborah Martin Kao and Charles A. Meyer Repnnted by permission of the Aaron Siskind Len Gittieman, and John Vinci. Foundation Foreword: Copynght © 1994 by Carl Chiarenza “The Photographs of Aaron Siskind" by Elaine de Kooning, Introduction: Toward a Personal Vision Copynght © Sid Grossman's installation photographs of Aaron 1951 , from typescnpt introduction to an exhibition of 1 994 by Charles A Meyer Siskind s "Tabernacle City" exhibition at the Photo Aaron Siskind’s photographs held at Charles Egan Gallery. Personal Vision in Aaron Siskind’s Documentary Practice: League. 1940, in a pnvate collection Repnnted by 63 East 57th Street. New York City. February 5th to 24th. Copynght ©1994 by Deborah Martin Kao permission of the Sid Grossman Foundation 1951, in the collection of Nathan Lyons. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, NY Académie Julian, Paris, France

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, NY Académie Julian, Paris, France Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, France Black Mountain College, Asheville, North Carolina Art Students League of New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Now, Then and Always, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY (forthcoming) JDJ | The Ice House, Garrison, NY 2020 Art Hysteri of Susan Weil: 70 Years of Innovation and Wit, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY [online exhibition] 2019 Once In A Blue Moon, Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich, Germany 2017 Susan Weil: Now and Then, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Susan Weil’s James Joyce: Shut Your Eyes and See, University at Buffalo, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, Buffalo, NY 2015 Poemumbles: 30 Years of Susan Weil’s Poem | Images, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, NC 2013 Time’s Pace: Recent Works by Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Reflections, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2008-2009 Motion Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA (2008); Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Hong Kong (2009) Trees, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Now & Then: A Retrospective of Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Ear’s Eye for James Joyce, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Moving Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Aronowitsch, Stockholm, Sweden 2000 Wanås, Knislinge, Sweden 1998 North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND Susan Weil: Full Circle, Black Mountain Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, -

Perpetual Inventory Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

Perpetual Inventory Author(s): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol. 88 (Spring, 1999), pp. 86-116 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/779226 . Accessed: 01/05/2013 15:51 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Wed, 1 May 2013 15:51:29 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PerpetualInventory* ROSALINDKRAUSS I wentin for myinterview for thisfantastic job. ... Thejob had a greatname-I might use itfor a painting-"PerpetualInventory." -Rauschenberg to Barbara Rose 1. Here are threedisconcerting remarks and one document: The firstsettles out from a discussion of the various strategies Robert Rauschenbergfound to defamiliarizeperception, so that, in Brian O'Doherty's terms,"the citydweller's rapid scan" would now displace old habits of seeing and "the art audience's stare" would yield to "the vernacularglance."I With its vora- ciousness,its lack of discrimination,its wanderingattention, -

Abstract Expressionism Community-Based Art

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Community Art Archive Art Summer 6-5-2015 Abstract Expressionism Community-based Art Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/cap-curr Part of the Art Education Commons Recommended Citation Community-based Art, "Abstract Expressionism" (2015). Community Art Archive. 2. http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/cap-curr/2 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community Art Archive by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Expressionism is a post–World War II art movement in American painting, developed in New York in the 1940s. It was the first specifically American movement to achieve international influence and put New York City at the center of the western art world, a role formerly filled by Paris. • Abstract Expressionism is a type of art in which the artist expresses himself purely through the use of form and color. It non-representational, or non-objective, art, which means that there are no actual objects represented. • Now considered to be the first American artistic movement of international importance, the term was originally used to describe the work of Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Arshile Gorky. • The movement can be more or less divided into two groups: Action Painting, typified by artists such as Pollock, de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Philip Guston, stressed the physical action involved in painting; Color Field Painting, practiced by Mark Rothko and Kenneth Noland, among others, was primarily concerned with exploring the effects of pure color on a canvas Abstract Scene, Jay Mueser. -

Susan Weil Once in a Blue Moon Jun 06 – Aug 31, 2019 Opening: Jun 05, 7 – 9 Pm

Susan Weil Once In A Blue Moon Jun 06 – Aug 31, 2019 Opening: Jun 05, 7 – 9 pm Susan Weil, Wandering Chairs, 1998, silver gelatin print, 113 x 302 cm. © S. Weil and C. Rauschenberg This exhibition marks the first time the US painter Susan Weil, b. 1930, presents her work at Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle. The artist studied at Black Mountain College under Josef Albers, together with Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly. Despite her abstract expressionist style, the artist, unlike her male counterparts, never let herself be influenced by the prevailing tendencies of the time. An important member of the New York School of Art, Susan Weil refuses to be categorized in any one style, and despite being influenced by abstract expressionism, she never completely forgot about the power of the figurative. The exhibition Once In A Blue Moon comprises seminal works from 1989 to the present. Taking familiar objects as a starting point, Susan Weil reduces all elements to their intrinsic nature to then reconstruct them in unexpected ensembles. Her work Wandering Chairs, a cooperation with her son Christopher Rauschenberg, consists of two chairs and the artist’s portrait, assembled like a puzzle from our different pieces. The viewer’s searching eye is first captured by the entire picture full of movement and disruption. Gradually, one is willing to engage in the artist’s game, constructing with her a new world in which the objects find each other in unanticipated ways. The composition of her works is always poetic, dynamic, and playful; it often seems as though the works dance on the walls. -

Susan Weil Press Release

JDJ Susan Weil February 27 - April 17, 2021 Over the course of her seventy year career, Susan Weil’s exuberant practice has drawn inspiration from nature, literature, art history, and her own lived experience. Weil came of age as an artist in the postwar period, studying under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College with Willem & Elaine de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg & Cy Twombly. Although she has deep roots in the New York School of Art, her work defes easy categorization. Central to Weil’s practice is her fascination with expressing time through motion, which she does in a number of ways, including her use of seriality, collage, and kinetic sculptural elements. She often works with blueprints, exposing the paper to light and using her body and other objects to make impressions, a technique that she introduced to her then-partner Robert Rauschenberg in 1949 and that she continues to use today. Weil’s oeuvre oscillates between the abstract and the concrete, and this exhibition brings together four bodies of work from the 1970s through the 1990s that reference the female body. Regardless of form or medium, there is a sense of vivacity, dynamism, and playfulness present in Weil’s work. One can sense the pleasure she fnds in everyday life—her delight in experiencing the passing of time as she moves through the world with a great sense of curiosity. The spray paint works on paper, exhibited here for the frst time in ffty years, express the fgure in a simple and contained way. Weil made these pieces in a free-fowing process, working on several at a time and allowing the compositions to come to her spontaneously. -

Gagosian Gallery

Slate.com November 11, 2010 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Robert Rauschenberg was the epic artist of the Postmodern era, splashing in every medium and style, sometimes all at once—a trait on clear view in his first major show since his death in 2008, put on by his estate at Gagosian Gallery's West 21stStreet branch in New York City. Rauschenberg came to New York in 1949, at age 24, as the Abstract Expressionists were on the rise, and though he emulated their brash brushstrokes and dynamic use of color, he rejected their grimness, their sense of art as an isolated struggle. Art, he thought, was serious, but it was also playful, and a way of merging himself with everything around him. He once said, "Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)" The critic Leo Steinberg, who saw Rauschenberg as the most inventive painter since Picasso, wrote, "What he invented above all was … a pictorial surface that let the world in again." Caryatid Cavalcade II/ROCI Chile, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 138½ x 260¾ inches. © Estate of Robert Rauschenberg/Licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y./DACS, London. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Robert McKeever. Rauschenberg's most boisterous, original works were the "combines"—painting- sculpture combinations splattered not only with streaks and drips of color but also with familiar objects: scraps of fabric, strips of wood, a necktie, newspaper clippings, a Coke bottle, metal signs, a zipper. Rauschenberg would walk around his block in Lower Manhattan and pick up street trash that he found interesting, then take it back to his studio and fit it into his art. -

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, New York Académie Julian, Paris

SUSAN WEIL Born 1930, New York, New York Académie Julian, Paris, France Black Mountain College, Asheville, North Carolina Arts Students League, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Art Hysteri of Susan Weil: 70 Years of Innovation and Wit, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY [online exhibition] 2019 Once In A Blue Moon, Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich, Germany 2017 Susan Weil: Now and Then, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Susan Weil’s James Joyce: Shut Your Eyes and See, University at Buffalo, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, Buffalo, NY 2015 Poemumbles: 30 Years of Susan Weil’s Poem | Images, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, NC 2013 Time’s Pace: Recent Works by Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Reflections, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2008-2009 Motion Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA (2008); Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Hong Kong (2009) Trees, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Now & Then: A Retrospective of Susan Weil, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Ear’s Eye for James Joyce, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Moving Pictures, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Aronowitsch, Stockholm, Sweden 2000 Wanås, Knislinge, Sweden 1998 North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND Susan Weil: Full Circle, Black Mountain Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, NC 1997 National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden Grafikens Hus, Södertälje, Sweden Anders Tornberg Gallery, Lund, Sweden 1996 Galerie Simone Gogniat, Basel, Switzerland