Manly Vice and Virtù

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

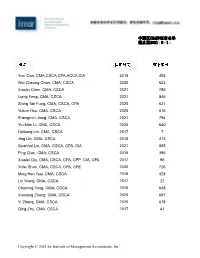

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Writing Taiwan History: Interpreting the Past in the Global Present

EATS III Paris, 2006 Writing Taiwan History: Interpreting the Past in the Global Present Ann Heylen Research Unit on Taiwanese Culture and Literature, Ruhr University Bochum [email protected] Do not cite, work in progress Introduction Concurrent with nation building is the construction of a national history to assure national cohesion. Hence, the collective memory is elevated to the standard of national myth and most often expressed in the master narrative. I may refer here to Michael Robinson’s observation that “the state constructs and maintains a ‘master narrative’ of nation which acts as an official ‘story of the nation’. This master narrative legitimates the existence of the state and nation internally; it is also projected externally, to legitimate a nations’ existence in the world community”.1 But in as much as memory is selective, so also is the state-sanctioned official narrative, and it has become commonplace that changes in the political order enhance and result in ideologically motivated re-writing of that history in spite of its claims at objectivity and truth. The study of the contemporary formation of Taiwan history and its historiography is no exception. In fact, the current activity in rewriting the history is compounded by an additional element, and one which is crucial to understanding the complexity of the issue. What makes Taiwanese historiography as a separate entity interesting, intriguing and complex is that the master-narrative is treated as a part of and embedded in Chinese history, and at the same time conditioned by the transition from a perceived to a real pressure from a larger nation, China, that lays claim on its territory, ethnicity, and past. -

Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

The London School of Economics and Political Science Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society Magdalena Wong A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London December 2016 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/ PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,927 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that different sections of my thesis were copy edited by Tiffany Wong, Emma Holland and Eona Bell for conventions of language, spelling and grammar. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how a hegemonic ideal that I refer to as the ‘able-responsible man' dominates the discourse and performance of masculinity in the city of Nanchong in Southwest China. This ideal, which is at the core of the modern folk theory of masculinity in Nanchong, centres on notions of men's ability (nengli) and responsibility (zeren). -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

CHINATOWN1-Web

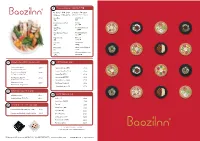

㑉ス⤇㔣╔╔㦓 Classic Hotpot Skewer Per Skewer ょ╔ £1.70 5 Skewer ╔ £7.90 13 Skewer ╔ £17.90 (Minimum Order 3 Skewer) Hot Dog Crab Stick 㦓⒎ 㨥⽄ Pork Luncheon Meat Konjac 㣙⏷㑠 ㄫ㲛ⰵ Beef Tripe Frozen Bean Curd ⊇㮠 ⛕⛛⡍ Fish Bamboo Wheel Fried Bean Curd 㻓 㱵⛛⡍ Pig’s Intestine Broccoli ➪⒎ 㣩⹊⪀ Fish Ball Cuttle Fish 㲋㠜 ㄱ㲋呷 Prawn Ball Okra (Lady’s Fingers) 㥪㠜 ㎯ⷋ Fish Tofu Chestnut Mushrooms ⛛⡍㲋 ⺃㽳ㄫ⤙ ORIENTAL MOCKTAIL 㝎㓧㯥㊹ HOT DRINKS 㑆㯥 Tender Touch ⥏䧾㨔 £3.50 Peppermint Tea ⌍⧣␒ £2.00 /\FKHHDQGDORHYHUD Lemon Grass Tea 㦓ぱ␒ £2.00 Green Vacation㓧⭯㋜ £3.50 /\FKHHDQGJUHHQWHD Lemon Tea ㆁを␒ £2.00 Jasmine Tea 䌪⺀⪀␒ £2.00 Pink Paradise ➻⨆㝢㜹 £3.50 :DWHUPHORQDQGDORHYHUD Brown Rice Tea ␄ゟ␒ £2.00 㠭㑓㎩⪋ Memories £3.50 Red Dates Tea ⨆㵌␒ £2.20 Watermelon and green tea. Grape Fruit Tea 䰔㽳␒ £2.20 MINERAL WATER ⷃ㐨㙦 SOFT DRINKS 㯥 ⷃ㐨㙦 Still Water £2.00 Sparkling Water㱸㋽ⷃ㐨㙦 £2.00 Coke £2.80 Diet Coke ☱㜽 £2.80 DESSERT OF THE DAY 㝦♇ 7up㋡㥢 £2.80 Herbal Tea 㠩⹝⭀ £2.80 ⥆䌵⡾ Homemade Herbal Grass Jelly £2.80 Soya Milk ⛛Ⰰ £2.80 Silver Ear and Lily Bulb Soup 㯢✜⊇⧩㜶 £3.00 Green Tea ␒ £2.80 Lychee Juice ⺁㺈㺏 £2.80 Aloe Vera Juice ⾵䍌㺏 £2.80 Plum Juice㚙み㜶 £2.80 Ύ&ƌĞĞtŝĮ͗ĂŽnjŝ/ŶŶ&ƌĞĞtŝĮ * Please note that dishes may not appear exactly as shown. Classic 1HZSRUW&W/RQGRQ:&+-6_7HO_ZZZEDR]LLQQFWFRP.com ⊔ᙐ㚱㱸➍㱉⍄ⳑ$OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG Noodle 奆 House Jiaozi / Wonton 儌㽳⒕㗐 Chicken & Shitake Mushroom Soup Noodles £10.50 Mixed Chengdu Dumpling with Spicy and ⛎⤙⬼㑠㜶ギ Fragrant Sauce㽻⧩㙦Ⱌ ^ĞƌǀĞĚŝŶƐĂǀŽƵƌLJďƌŽƚŚ͘ 3RUN)LOOLQJDQG3UDZQ)LOOLQJ £10.90 £9.50 Classic Chicken Noodles Mixed Wanton in Savoury Broth with ⸿㽳⬼⛃ギ Lever Seaweed 㽻⧩⒕㗐 dŽƉƉĞĚǁŝƚŚĂƌŽŵĂƟĐĐŚŝĐŬĞŶǁŝƚŚĐŚŝůůŝĞƐĂŶĚƐƉŝĐĞĚ͘ 3RUN)LOOLQJDQG3UDZQ)LOOLQJ £10.90 Zhajiang Noodles £9.50 Traditional Dumpling ⌝➝儌㽳 㷌Ⰸギ Topped with minced pork,ĨĞƌŵĞŶƚĞĚďĞĂŶƐĂƵĐĞ 3RUN)LOOLQJ £8.90 and salad. -

Breakfast Healthy Salad

MIE GORENG AKA FRIED NOODLES 76,543 BREAKFAST Chicken or vegetable fried noodle, poached egg, SALAD pickled vegetables and shrimp cracker POFFERTJES 67,890 CHICKPEAS SALAD 76,543 A dozen small pancakes, served with dusting sugar Enjoy onions, tomatoes and feta cheese combined BUBUR 56,789 with chickpeas and a light dressing NUTELLA PANCAKES (N) 76,543 Our Bubur is served with cakwe / youtiao - Youtiao, A stack of 4 pancakes with is a long goldenbrown deep-fried strip of dough CAESAR SALAD (N) 98,765 a sumptuous amount of Nutella commonly eaten in China and in other East and Baby romaine, parmigiana, sous vide egg, Southeast Asian cuisines. Conventionally, garlic bread, fried caper, parsley, crispy bacon, STUFFED PAPRIKA (V) 87,654 youtiao are lightly salted and grilled chicken and caesar dressing Filled paprika with steamed egg white, made so they can be torn lengthwise in two sautéed mushrooms and tomato. POMELO SALAD (V) 98,765 BANANA NUTELLA WRAP (N) 76,543 Pamelo with grilled chicken, coriander, ANANTARA EGG BENEDICT (P) 123,456 Chocolate-hazelnut spread covers a warm tortilla mint leaft, shallot and jim sauce 2 softly poached eggs, served on a layered rolled around a banana. Pan Fried to perfection sour dough toast with salad,Parma ham and For the sweet tooth amongst us served with a rich truffle hollandaise sauce HEALTHY to make the entire experience mesmerising ANANTARA BREAKFAST 123,456 2 eggs any kind ( Poached, sunny side up, scrambled) QUINOA AVOCADOSALMON 145,678 NASI BABI BALI (P) 67,890 2 slices of bacon, 2 grilled sausages, 2 hash brown, Quinoa, mixed with avocado, cherry tomato, basil Braised Pork Belly, Krupuk Bali, vegetables 2 pieces of sour bread, steak, grilled tomato, and grilled salmon flakes sautéed mushrooms, salad and baked beans EGG WHITE OMELETTE (V) 67,890 CHIRASHI 176,543 Egg white omelet, served with cherry tomatoes and MIE AYAM 67,890 Chirashi, also called chirashizushi (ちらし寿司) is one sautéed mushrooms - very low on cholesterol packed Mie ayam, mi ayam or bakmi ayam is a common of my favourite Japanese meals. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods: vast majority, who were based in urban centers, could ill afford to be indifferent to money and the Diaries of the Toyama Family commerce. Largely divorced from the land and of Hachinohe incumbent upon the lord for their livelihood, usually disbursed in the form of stipends, samu- © Constantine N. Vaporis, University of rai were, willy-nilly, drawn into the commercial Maryland, Baltimore County economy. While the playful (gesaku) literature of the late Tokugawa period tended to portray them as unrefined “country samurai” (inaka samurai, Introduction i.e. samurai from the provincial castle towns) a Samurai are often depicted in popular repre- reading of personal diaries kept by samurai re- sentations as indifferent to—if not disdainful veals that, far from exhibiting a lack of concern of—monetary affairs, leading a life devoted to for monetary affairs, they were keenly price con- the study of the twin ways of scholastic, meaning scious, having no real alternative but to learn the largely Confucian, learning and martial arts. Fu- art of thrift. This was true of Edo-based samurai kuzawa Yukichi, reminiscing about his younger as well, despite the fact that unlike their cohorts days, would have us believe that they “were in the domain they were largely spared the ashamed of being seen handling money.” He forced paybacks, infamously dubbed “loans to maintained that “it was customary for samurai to the lord” (onkariage), that most domain govern- wrap their faces with hand-towels and go out ments resorted to by the beginning of the eight- after dark whenever they had an errand to do” in eenth century.3 order to avoid being seen engaging in commerce. -

Taiwan in the Twentieth Century: an Introduction Richard Louis

Taiwan in the Twentieth Century: An Introduction Richard Louis Edmonds and Steven M. Goldstein For much of the past half-century, Taiwan’s development has been inextricably tied to the drama of the Chinese civil war and the Cold War in Asia. Both the government on Taiwan and many of its supporters abroad have sought to link the island’s history with that of the mainland. The result has been partially to obscure the distinctive history of Taiwan and, with this, to ignore factors which have decisively shaped the development of the island. The bulk of the papers in this volume seek to contribute to the ongoing efforts of scholars in Taiwan and abroad to illuminate the early 20th-century portion of this history and to join it to discussions of the post-war evolution of the island. With the end of the Second World War, Taiwan was returned to China after 50 years as a Japanese colony. The Kuomintang-controlled Republic of China on the mainland took over the administration of Taiwan almost immediately, subjecting its citizens to a brutal, authoritarian rule. In 1949, after defeat on the mainland, Chiang Kai-shek brought the remnants of that government to Taiwan, where, claiming to be the legitimate govern- ment of all of China, he established a temporary national capital in the one province completely under its control. It seemed at the time that this hollow claim would be silenced by an imminent Communist invasion. The outbreak of the Korean War, how- ever, and fears of Chinese Communist expansion brought renewed econ- omic, military and diplomatic support from the United States of America. -

Problem Gambling: How Japan Could Actually Become the Next Las Vegas

[Type here] PROBLEM GAMBLING: HOW JAPAN COULD ACTUALLY BECOME THE NEXT LAS VEGAS Jennifer Roberts and Ted Johnson INTRODUCTION Although with each passing day it appears less likely that integrated resorts with legalized gaming will become part of the Tokyo landscape in time for the city’s hosting of the summer Olympics in 20201, there is still substantial international interest in whether Japan will implement a regulatory system to oversee casino-style gaming. In 2001, Macau opened its doors for outside companies to conduct casino gaming operations as part of its modernized gaming regulatory system.2 At that time, it was believed that Macau would become the next Las Vegas.3 Just a few years after the new resorts opened, many operated by Las Vegas casino company powerhouses, Macau surpassed Las Vegas as the “gambling center” at one point.4 With tighter restrictions and crackdowns on corruption, Macau has since experienced declines in gaming revenue.5 When other countries across Asia have either contemplated or adopted gaming regulatory systems, it is often believed that they could become the 1 See 2020 Host City Election, OLYMPIC.ORG, http://www.olympic.org/2020-host- city-election (last visited Oct. 25, 2015). 2 Macau Gaming Summary, UNLV CTR. FOR GAMING RES., http://gaming. unlv.edu/ abstract/macau.html (last visited Oct. 25, 2015). 3 David Lung, Introduction: The Future of Macao’s Past, in THE CONSERVATION OF URBAN HERITAGE: MACAO VISION – INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE xiii, xiii (The Cultural Inst. of the Macao S. A. R. Gov’t: Studies, Research & Publ’ns Div. 2002), http://www.macauheritage.net/en/knowledge/vision/vision_xxi.pdf (noting, in 2002, of outside investment as possibly creating a “Las Vegas of the East”). -

Hedging Your Bets: Is Fantasy Sports Betting Insurance Really ‘Insurance’?

HEDGING YOUR BETS: IS FANTASY SPORTS BETTING INSURANCE REALLY ‘INSURANCE’? Haley A. Hinton* I. INTRODUCTION Sports betting is an animal of both the past and the future: it goes through the ebbs and flows of federal and state regulations and provides both positive and negative repercussions to society. While opponents note the adverse effects of sports betting on the integrity of professional and collegiate sporting events and gambling habits, proponents point to massive public interest, the benefits to state economies, and the embracement among many professional sports leagues. Fantasy sports gaming has engaged people from all walks of life and created its own culture and industry by allowing participants to manage their own fictional professional teams from home. Sports betting insurance—particularly fantasy sports insurance which protects participants in the event of a fantasy athlete’s injury—has prompted a new question in insurance law: is fantasy sports insurance really “insurance?” This question is especially prevalent in Connecticut—a state that has contemplated legalizing sports betting and recognizes the carve out for legalized fantasy sports games. Because fantasy sports insurance—such as the coverage underwritten by Fantasy Player Protect and Rotosurance—satisfy the elements of insurance, fantasy sports insurance must be regulated accordingly. In addition, the Connecticut legislature must take an active role in considering what it means for fantasy participants to “hedge their bets:” carefully balancing public policy with potential economic benefits. * B.A. Political Science and Law, Science, and Technology in the Accelerated Program in Law, University of Connecticut (CT) (2019). J.D. Candidate, May 2021, University of Connecticut School of Law; Editor-in-Chief, Volume 27, Connecticut Insurance Law Journal. -

Cycling Taiwan – Great Rides in the Bicycle Kingdom

Great Rides in the Bicycle Kingdom Cycling Taiwan Peak-to-coast tours in Taiwan’s top scenic areas Island-wide bicycle excursions Routes for all types of cyclists Family-friendly cycling fun Tourism Bureau, M.O.T.C. Words from the Director-General Taiwan has vigorously promoted bicycle tourism in recent years. Its efforts include the creation of an extensive network of bicycle routes that has raised Taiwan’s profile on the international tourism map and earned the island a spot among the well-known travel magazine, Lonely Planet’s, best places to visit in 2012. With scenic beauty and tasty cuisine along the way, these routes are attracting growing ranks of cyclists from around the world. This guide introduces 26 bikeways in 12 national scenic areas in Taiwan, including 25 family-friendly routes and, in Alishan, one competition-level route. Cyclists can experience the fascinating geology of the Jinshan Hot Spring area on the North Coast along the Fengzhimen and Jinshan-Wanli bikeways, or follow a former rail line through the Old Caoling Tunnel along the Longmen-Yanliao and Old Caoling bikeways. Riders on the Yuetan and Xiangshan bikeways can enjoy the scenic beauty of Sun Moon Lake, while the natural and cultural charms of the Tri-Mountain area await along the Emei Lake Bike Path and Ershui Bikeway. This guide also introduces the Wushantou Hatta and Baihe bikeways in the Siraya National Scenic Area, the Aogu Wetlands and Beimen bikeways on the Southwest Coast, and the Round-the-Bay Bikeway at Dapeng Bay. Indigenous culture is among the attractions along the Anpo Tourist Cycle Path in Maolin and the Shimen-Changbin Bikeway, Sanxiantai Bike Route, and Taiyuan Valley Bikeway on the East Coast. -

Design and Realization of a Humanoid Robot for Fast and Autonomous Bipedal Locomotion

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Lehrstuhl für Angewandte Mechanik Design and Realization of a Humanoid Robot for Fast and Autonomous Bipedal Locomotion Entwurf und Realisierung eines Humanoiden Roboters für Schnelles und Autonomes Laufen Dipl.-Ing. Univ. Sebastian Lohmeier Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Maschinenwesen der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor-Ingenieurs (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Udo Lindemann Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Heinz Ulbrich 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Horst Baier Die Dissertation wurde am 2. Juni 2010 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Maschinenwesen am 21. Oktober 2010 angenommen. Colophon The original source for this thesis was edited in GNU Emacs and aucTEX, typeset using pdfLATEX in an automated process using GNU make, and output as PDF. The document was compiled with the LATEX 2" class AMdiss (based on the KOMA-Script class scrreprt). AMdiss is part of the AMclasses bundle that was developed by the author for writing term papers, Diploma theses and dissertations at the Institute of Applied Mechanics, Technische Universität München. Photographs and CAD screenshots were processed and enhanced with THE GIMP. Most vector graphics were drawn with CorelDraw X3, exported as Encapsulated PostScript, and edited with psfrag to obtain high-quality labeling. Some smaller and text-heavy graphics (flowcharts, etc.), as well as diagrams were created using PSTricks. The plot raw data were preprocessed with Matlab. In order to use the PostScript- based LATEX packages with pdfLATEX, a toolchain based on pst-pdf and Ghostscript was used.