Animal Sanctity and Animal Sacrifice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About the Crew Masaaki Tanabe

ABOUT THE CREW MASAAKI TANABE (Director) Masaaki Tanabe personally felt the A-bomb devastation and loss of his family as a young boy. After years of struggling to even speak about his unconscionable experience, he interviewed several hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) and former residents of Hiroshima, who have first-hand knowledge of life before the bomb. As a Hiroshima A-bomb survivor, this documentary is his mission to remember what was lost and the hope for future peace. Tanabe is a documentary film director, author, and the president of Knack Imagery Production Center. He was born in his family home directly adjacent to the Industrial Promotional Hall which is now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome. It stands less than 200 feet away from ground zero. Along with him, his mother and baby brother had been evacuated 37 miles away to his grandmother’s house in Yamaguchi Prefecture. Two days before the bomb fell, his mother and brother had returned to Hiroshima to care for his father. At 7 years old, he went with his grandmother into the devastated city to look for his mother, father, and brother. His mother and baby brother are believed to have died in the house they grew up in. His father was badly burned and reached his grandmother’s house in Yamaguchi days later, but did not survive. He lost his entire family. As a young man, Tanabe was exposed to Western culture and learned to appreciate American and European cinema. Classic movies changed his outlook on life. They changed his view of America. -

Hitchhiking: the Travelling Female Body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 Hitchhiking: the travelling female body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Plumb, Vivienne, Hitchhiking: the travelling female body, Doctorate of Creative Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2012. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3913 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Hitchhiking: the travelling female body A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctorate of Creative Arts from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Vivienne Plumb M.A. B.A. (Victoria University, N.Z.) School of Creative Arts, Faculty of Law, Humanities & the Arts. 2012 i CERTIFICATION I, Vivienne Plumb, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Journalism and Creative Writing, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Vivienne Plumb November 30th, 2012. ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the support of my friends and family throughout the period of time that I have worked on my thesis; and to acknowledge Professor Robyn Longhurst and her work on space and place, and I would also like to express sincerest thanks to my academic supervisor, Dr Shady Cosgrove, Sub Dean in the Creative Arts Faculty. Finally, I would like to thank the staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, in particular Olena Cullen, Teaching and Learning Manager, Creative Arts Faculty, who has always had time to help with any problems. -

Death Valley Junior Ranger Book

How to be a Junior Ranger Complete the number of activities for the animal level i. you would like to achieve. Circle that animal below. Roadrunner Level: Chuckwalla Level: Bighorn Sheep Level: at least 4 activities at least 6 activities at least 9 activities Compare Death Valley to where you live. You can watch the park movie at the Furnace Creek Visitor Center for inspiration. How is Death Valley similar How is Death Valley different to your home? from your home? ~o Become an Official Junior Ranger! Go to a visitor center or ranger station in Death Valley National Park. Show a ranger this book, and tell them about your adventure. You will be sworn in as an official Junior Ranger and get a badge! Junior Ranger patches Books may also be are available for purchase mailed to: at the bookstore. Just show Death Valley National Park Junior Ranger Program the certificate on the PO Box 579 back of this book! Death Valley, CA 92328 Let's get started! Packing for Your Adventure Before we go out on our Junior Ranger adventure, we must make sure we are prepared! If we bring the right things, we can have a fun and safe adventure in Death Valley! First things first-bring plenty of water, and remind your family to drink it! Help me pack for my hike by circling what I should bring! How might summer visitors prepare differently than visitors in the winter? Map of Your Adventure This is a map of your adventure in Death Valley. Draw the path you traveled to explore the hottest, driest, and lowest national park in the United States! Circle the places that you visited, and fill in the names of the blank spaces on the map. -

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

The Shawl by Cynthia Ozick

The Shawl by Cynthia Ozick 1 Table of Contents The Shawl “Just as you can’t About the Book.................................................... 3 grasp anything About the Author ................................................. 5 Historical and Literary Context .............................. 7 without an Other Works/Adaptations ..................................... 9 opposable thumb, Discussion Questions.......................................... 10 you can’t write Additional Resources .......................................... 11 Credits .............................................................. 12 anything without the aid of metaphor. Metaphor is the mind’s opposable thumb.” Preface What is the NEA Big Read? No event in modern history has inspired so many books as A program of the National Endowment for the Arts, NEA Big the Holocaust. This monumental atrocity has compelled Read broadens our understanding of our world, our thousands of writers to reexamine their notions of history, communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a humanity, morality, and even theology. None of these good book. Managed by Arts Midwest, this initiative offers books, however, is quite like Cynthia Ozick's The Shawl—a grants to support innovative community reading programs remarkable feat of fiction which starts in darkest despair and designed around a single book. brings us, without simplification or condescension, to a glimmer of redemption. A great book combines enrichment with enchantment. It awakens our imagination and enlarges our humanity. -

Death, Transition, and Resilience: a Narrative Study of the Academic Persistence of Bereaved College Students

DEATH, TRANSITION, AND RESILIENCE: A NARRATIVE STUDY OF THE ACADEMIC PERSISTENCE OF BEREAVED COLLEGE STUDENTS Cari Ann Urabe A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2020 Committee: Maureen E. Wilson, Committee Co-Chair D-L Stewart, Committee Co-Chair Paul Cesarini Graduate Faculty Representative Christina J. Lunceford © 2020 Cari Ann Urabe All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Maureen E. Wilson, Committee Co-Chair D-L Stewart, Committee Co-Chair This study used narrative inquiry to focus on the lived experiences of undergraduate and graduate students who have experienced a significant death loss during their studies and have academically persisted in the face of adversity. The purpose of this research was to understand and describe how undergraduate and graduate students academically persist within higher education after a significant death loss. Providing this affirmative narrative illuminated the educational resilience that occurs following a death loss experience. Using educational resilience as the conceptual model and Schlossberg’s transition theory as the theoretical framework, the overarching research question that guided this study was: What are the narratives of bereaved college students who academically persist in the face of adversity? Participants included seven undergraduate and graduate students from three institutions of higher education across the United States. Participants engaged in two semi-structured interviews and an electronic journaling activity to share their death loss experience. Interviews were conducted face-to-face and virtually. Composite narratives were used to present the data from this study. The seven participants in this study were highlighted through four composite characters who met monthly at a Death Café. -

'The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen Upon Us'

‘The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen upon Us’. The Representation of Gender in Zombie Films, 1968-2013 Leon van Amsterdam Student number: s1141627 Leiden University MA History: Cities, Migration and Global Interdependence Thesis supervisor: Marion Pluskota 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Theory ................................................................................................................................. 6 Literature Review ............................................................................................................... 9 Material ............................................................................................................................ 13 Method ............................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2: A history of the zombie and its cultural significance ............................................. 18 Race and gender representations in early zombie films .................................................. 18 The sci-fi zombie and Romero’s ghoulish zombie ............................................................ 22 The loss and return of social anxiety in the zombie genre .............................................. 26 Chapter 3: (Post)feminism in American politics and films ....................................................... 30 Protofeminism ................................................................................................................. -

The Use of Animals in Sports

Existence, Breeding, a,nd Rights: The Use of Animals in Sports Donald Scherer Bowling Green State University Against these lines of argument one frequently encounters a certain objection. It is argued that since the animals for fighting, hunting and racing exist only because they have been bred for such human uses, human beings are justified in so treating them. The purpose of this paper is to evaluate this line ofobjection, or to speak more precisely, to evaluate the two distinct objections implicit in this line. For the objection may be either that (l) the present uses of the animals are justified because they are better for the animals than the Standardly, philosophical arguments about the alternative, namely non-existence, or that quality of treatment human beings owe nonhuman animals! rest on two bases. Peter Singer is famous (2) breeding an animal for a purpose gives the for arguing from the capacity of animals to feel pain breeders (transferable) rights over what they to the conclusion that since almost none of the pain have bred. human beings cause animals is necessary, almost none of it is morally justifiable (Singer, 1989, pp. 78-79). I shall pursue these alternatives sequentially. Singer rests his case on the premise that who suffers pain does not affect the badness of the suffering, so The Value of Existence that, without strong justification, the infliction of pain is universally wrong (Ibid., pp. 77-78). Tom Regan is The strength ofthe first form ofthe objection rests on equally famous for his argument that the beliefs and a common intuition comparing the values of existence desires which normal one year-old mammals clearly and non-existence. -

DAVID FLUHR (Continued)

David E. Fluhr, C.A.S. Re-Recording Mixer Awards & Nominations 1 CAS Award; 6 CAS Nominations 9 Emmy Awards; 38 Emmy Nominations (1984-1998) Selected Credits Director/Picture Editor/Production Co. TINKER BELL AND THE GREAT FAIRY RESCUE Bradley Raymond/ Lisa Linder & Kevin Locarro/Disney Toon Studios TANGLED Nathan Greno & Byron Howard/Tim Mertens/ Walt Disney Pic STEP UP 3-D John Chu/Andrew Marcus/Walt Disney Pic PREP & LANDING Kevin Deters & Stevie Wermers/William Caparella/ Walt Disney Pic THE PRINCESS AND THE FROG Ron Clements & John Musker/Jeff Draheim/ Walt Disney Pic SURROGATES Jonathan Mostow/Kevin Stitt/Walt Disney Pic TINKER BELL AND THE LOST TREASURE Klay Hall/Alan Stewart/Disney Toon Studios THE JONAS BROTHERS 3D CONCERT Bruce Hendricks/ Michael Tronick/Walt Disney Pic THE UNINVITED (addl. re-recording) Charles & Thomas Guard/Jim Page/ DreamWorks SUPER RHINO (Short Film) Nathan Greno/ Shannon Stein/ Walt Disney Pic BOLT Byron Howard & Chris Williams/Walt Disney Pic HANNAH MONTANA BEST OF BOTH Bruce Hendricks/Michael Tronick/Walt Disney Pic WORLDS CONCERT TOUR-3D COLLEGE ROAD TRIP Roger Kumble/Roger Bondelli/ Walt Disney Pic ENCHANTED (music re-recording mixer) Kevin Lima/Gregory Perler/Walt Disney Pictures THE GUARDIAN Andrew Davis/Dennis Virkler/Touchstone Pictures MEET THE ROBINSONS Stephen Anderson/Ellen Keneshea/Walt Disney Pic THE LOOKOUT Scott Frank/Jill Savitt/Miramax, Spyglass BARNYARD Steve Oedekerk/Paul Calder/Paramount BLACK SNAKE MOAN Craig Brewer/Billy Fox/Paramount CHICKEN LITTLE Mark Dindal/Dan Molina/Walt Disney Pictures THE GREAT RAID John Dahl/Pietro Scalia/Miramax THE GREATEST GAME EVER PLAYED Bill Paxton/Elliot Graham/Walt Disney Pictures THE ALAMO John Lee Hancock/Eric Beason/Imagine Ent. -

04 17 2012 Sect 2 (Pdf)

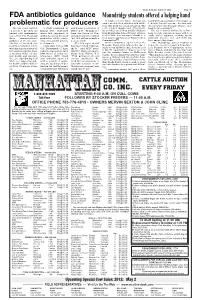

Grass & Grain, April 17, 2012 Page 17 FDA antibiotics guidance Moundridge students offered a helping hand In tough economic times, often parents Communities presentation in the paper, so problematic for producers cannot provide their children with all the I thought I would sign up,” Goering said. tools they need for a good education. The “It’s great for the Monsanto Fund to give The loss of and restrict- A study conducted by and disease prevention. A costs of school supplies and extracurricu- back to our community.” ed access to products ex- Kansas State University 2001 report, “Hogging It,” lar activities can add up quickly. Students The school district will use the $2,500 to pected with implementa- shows that opponents of from the Union of Con- from Moundridge School District will now help provide students in need with food tion of the U.S. Food and antibiotics use in livestock cerned Scientists claimed need a little less assistance thanks to a cards, school supplies, clothing, sports Drug Administration’s production wildly overes- that 10.3 million pounds a local farmer and America’s Farmers Grow physicals, practice gear, and field trip SM guidance on the use of an- timate the amount given to year are used. Communities . fees, among other items. tibiotics in livestock and food animals. “The UCS report should Grow Communities, sponsored by the “The Moundridge School District is poultry production likely Using data from a 2006 have been titled ‘Fabricat- Monsanto Fund, gives farmers the oppor- honored to receive a donation from Amer- will disproportionately af- U.S. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.